There are fears that agricultural subsidies could attract farmers with low returns to use new technologies. Evidence from Bangladesh shows that without subsidies, the price of agricultural inputs is actually a barrier to adoption, highlighting that high prices, combined with credit constraints, can hold back technology adoption in agriculture.

Subsidies are a key policy instrument for increasing farmers’ access to new technologies, but do they always improve efficiency? Lower prices can lead to greater adoption, but they may also attract farmers with lower returns. On the flip side, adoption may be constrained by factors such as limited credit access—preventing high-return farmers from taking up new technologies in the absence of subsidies or price discounts.

In my research study (Mahmoud 2024), I examine whether lower prices allocate improved wheat seeds to farmers with lower or higher returns. The research focuses on Bangladesh, one of the world’s largest wheat importers, where an improved wheat seed variety, BARI Gom 33, was introduced to combat wheat blast, a devastating crop disease.

Experimental design: Measuring the impact of improved seeds among non-buyers

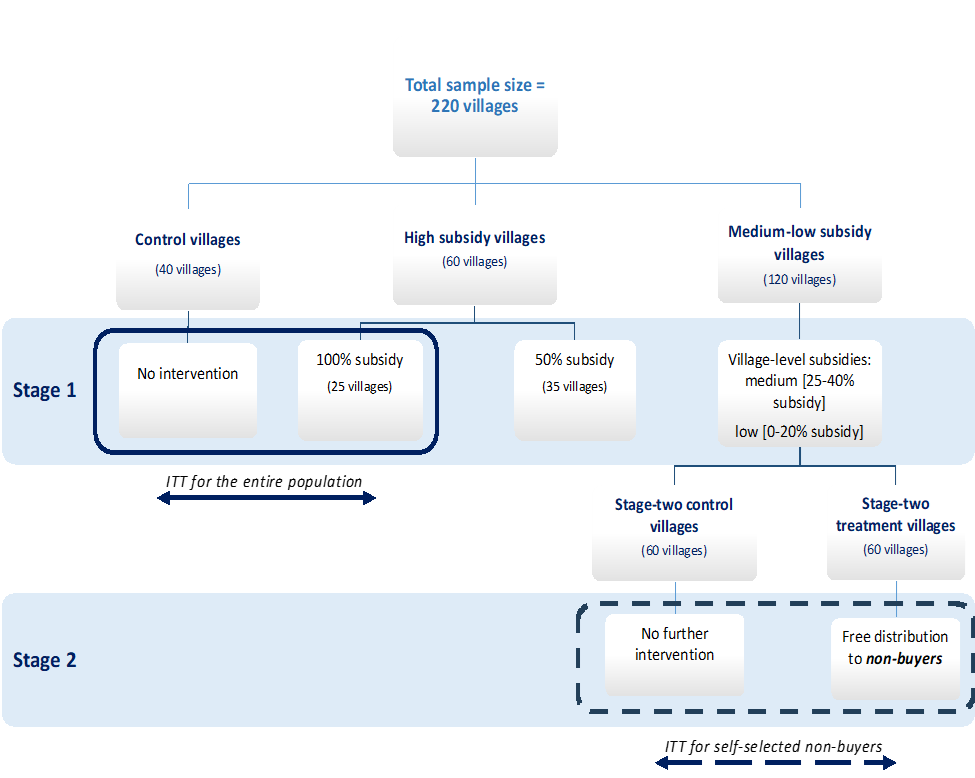

Figure 1: Experimental design

As shown in Figure 1, the study uses a two-stage randomised controlled trial (RCT) across 220 villages. In the first stage, villages were randomly assigned to either a control group (40 villages) or a treatment group (180 villages), where seed subsidies were randomised at high (50–100%), medium (25–40%), and low (0–20%) levels. In the second stage, villages in the medium- and low-subsidy categories were further randomised into stage-two treatment or stage-two control. In stage-two treatment villages, farmers who did not buy seeds in the first stage were offered the same seed package for free before planting. In stage-two control villages, no additional intervention was provided. Thus, stage-two treatment randomised free distribution among non-buyers from stage one. Both stages were implemented within a single agricultural season prior to planting.

This two-stage design allows for comparing outcomes across different groups. First, the randomisation of free distribution in stage one allows me to estimate treatment effects over the entire population. Second, the randomisation of free distribution in stage two allows me to estimate treatment effects among non-buyers. Using these estimates, I examine whether farmers who decline to buy seeds at positive prices have lower, higher, or similar returns compared to the average farmer.

The new seed variety used in the experiment was introduced in an environment where farmers simultaneously decide which crops to grow and which seed varieties to use. Heterogeneity in treatment effects across farmers may arise due to factors such as market access, substitute crops, soil quality, and weather conditions. Some of these factors are known to farmers when they make purchase decisions, while others are uncertain.

The impact of prices on adoption and usage of new seeds

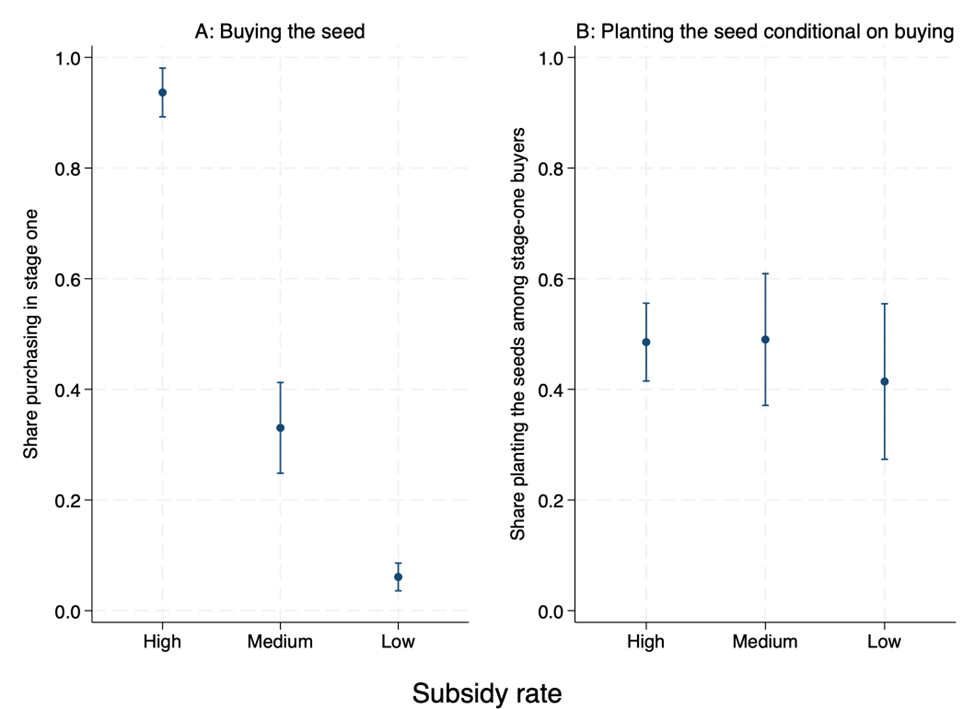

The first stage of the experiment reveals that farmers are highly sensitive to seed prices, particularly in the subsidy range of 50% to 0%. As shown in Panel A of Figure 2, moving from a high to a low subsidy level decreases demand from 94% to 6%. An important question is whether farmers who do not buy seeds expect low returns or face constraints that prevent them from purchasing? The results on actual adoption among seed buyers, presented in Panel B of Figure 2, suggest that the subsidy does not sort farmers based on their likelihood of planting the seeds. The likelihood of planting the seeds is similar across farmers who took up the seeds at different subsidy levels.

Figure 2: Demand vs. usage of seeds

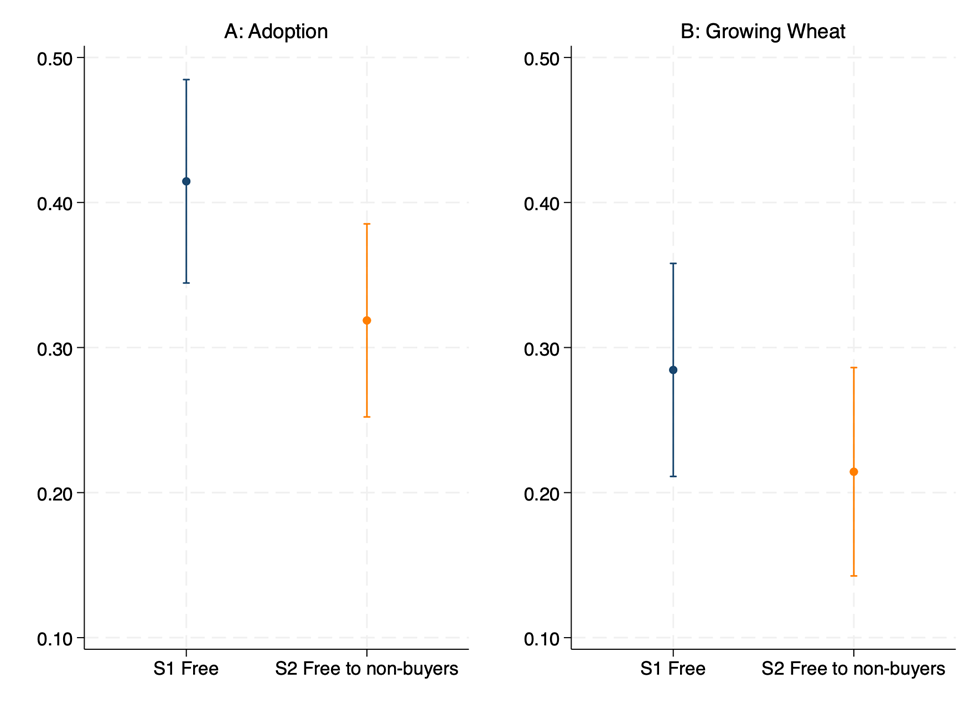

The second stage of the experiment shows that farmers who decline to buy seeds in stage one end up planting the seed (rather than eating it or passing it to other farmers). As shown in Panel A of Figure 3, stage-two free distribution increased adoption by 32 percentage points, compared to a 41-percentage point increase in stage-one free-distribution villages. In other words, the effect of stage-two free distribution was about 78% as large as that of stage-one free distribution.

Moreover, Panel B of Figure 3 shows that free distribution significantly influenced crop choices, a critical decision in this context. The treatment effect of stage-two free distribution on wheat cultivation among non-buyers (a 21-percentage point increase) was not statistically different from the effect of stage-one free distribution (a 28-percentage point increase). These effects on adoption and wheat cultivation persisted one year after the intervention, indicating that price is a significant barrier even for farmers willing to adopt the new seed.

Figure 3: Impacts on adoption and wheat cultivation

Impacts of subsidised seeds on revenues and profits

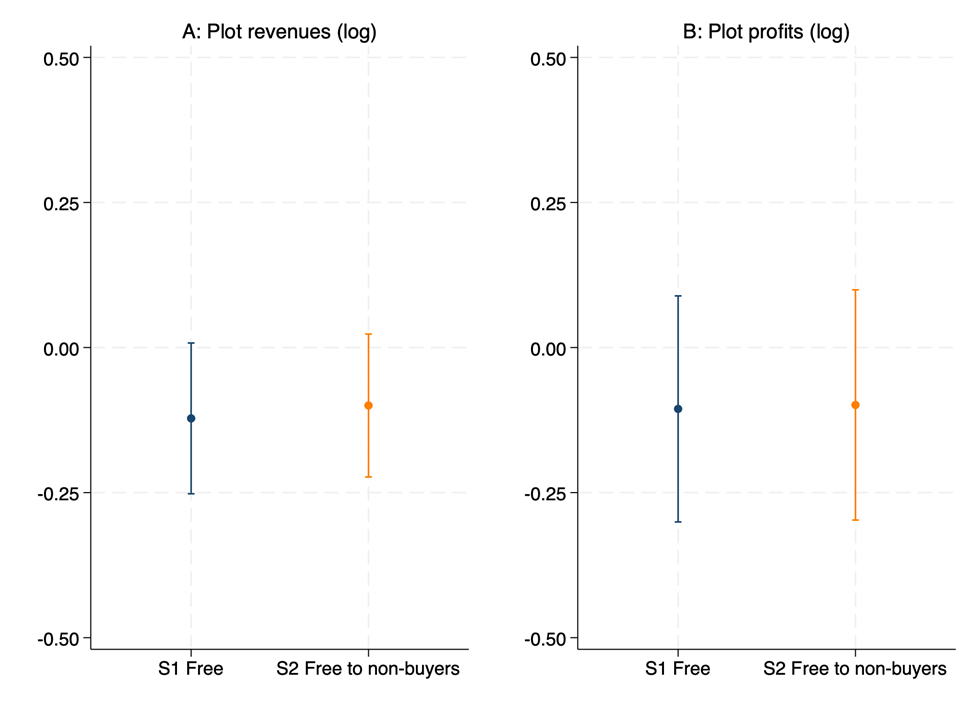

Contrary to concerns about low returns, I find no evidence that non-buyers avoided purchasing seeds due to lower-than-average profits. Both stage-one and stage-two free distribution had comparable effects on plot-level revenues and profits, as shown in Figure 4. While the profit estimates are noisy, I can confidently can rule out that the returns of non-buyers are lower (or higher) than the returns of the average farmer by more than 30%.

Figure 4: Impacts on revenues and profits

Using the two-stage design, I also infer the returns of farmers who would have been induced to buy seeds if the subsidy increased from low to medium. These “would-be buyers” at the medium subsidy level have higher-than-average returns. Specifically, the inferred expected profits for would-be buyers at the medium subsidy are 60,000 BDT/acre, compared to an average profit of 40,000 BDT/acre in stage-one free-distribution villages. This suggests that lowering prices did not lead to inefficient allocation toward low-return farmers.

A potential mechanism: Credit constraints

Several mechanisms may explain why non-buyers opt out of purchasing the improved seed despite not having lower returns. While no single mechanism can fully account for the results, I provide suggestive evidence that binding credit constraints may play a key role. Empirically, non-buyers most responsive to stage-two free distribution were more likely to report binding credit constraints at baseline. Theoretically, binding credit constraints can create a gap between revealed willingness-to-pay and expected returns, leading farmers to opt out even when expected returns are not too low.

Policy implications and further research on agricultural subsidies

This research provides novel experimental evidence that farmers do not necessarily select into purchasing improved inputs based on their returns, despite substantial heterogeneity in returns. This finding implies that policymakers aiming to increase the dissemination of agricultural technologies cannot rely solely on market prices to target high-return farmers.

Further research is needed to explore alternative approaches for addressing market frictions that hinder the role of prices in sorting farmers by returns. One potential approach is to implement a targeting mechanism independent of prices. For example, the second wave of agricultural input subsidies in Sub-Saharan Africa employs decentralised targeting by local leaders to identify high-return farmers. While this approach may be justified when prices fail to sort farmers effectively (Basurto et al. 2020), it raises concerns about nepotism and elite capture (Pan and Christiaensen 2012). Another promising approach involves conditional subsidies, such that farmers must meet specific agronomic criteria to qualify for the subsidy, ensuring that the inputs are used productively.

References

Basurto, M P, P Dupas, and J Robinson (2020), “Decentralization and efficiency of subsidy targeting: Evidence from chiefs in rural Malawi,” Journal of Public Economics, 185: 104047.

Mahmoud, M (2024), “Pricing and allocation of new agricultural technologies,” Unpublished manuscript.

Pan, L, and L Christiaensen (2012), “Who is vouching for the input voucher? Decentralized targeting and elite capture in Tanzania,” World Development, 40(8): 1619–1633.