Peru’s experience, where transfers to local governments were funded by natural resource tax revenues and had a host of economic benefits in non-extractive areas, highlights the importance of fiscal redistribution in taking advantage of natural resource wealth.

The effectiveness of fiscal policy in promoting economic growth has been a long-standing debate in economics, dating back to Keynes’s groundbreaking work. There are various channels through which an influx of resources can affect local economies. On the one hand, transfers can generate positive multiplier effects through investments in infrastructure and demand for local inputs, leading to higher levels of formal employment, entrepreneurship, and household consumption (Corbi et al. 2018, Chodorow-Reich 2019, Egger et al. 2022), particularly when there is slack in the economy (Walker et al. 2024). On the other hand, injecting money into local economies may generate inflationary pressures (Cunha et al. 2019), and if it is channelled through the public sector, it can crowd out private economic activity — for example, by creating labour rationing (Jaimovich and Rud 2014, Breza et al. 2021) — or result in rent-seeking and waste (Caselli and Michaels 2013, Bancalari 2024).

In a recent paper (Bancalari and Rud 2024), we study how plausibly exogenous transfers to local governments that affect the size and composition of municipal public expenditures affect local economies. In particular, we leverage a legal framework (known as Canon) that redistributes natural resource tax revenues, primarily from mining, among Peruvian municipalities between 2006 and 2018. The stated aim of this policy was to close poverty and infrastructure gaps through the fiscal redistribution of resource rents that were ring-fenced for public investment to promote local economic development.

Peru is an ideal context to study fiscal redistribution

This context offers an ideal setting to study fiscal redistribution. First, we examine a substantial fiscal shock to low-income municipalities: between 2006 and 2018, the Peruvian government redistributed USD 24 billion (2007 PPP), approximately 2% of the GDP of recipient regions annually. These windfalls represented over 20% of the median municipality’s annual budget. The average recipient municipality is largely rural, poor, has limited tax and technical capacity, and operates with a small bureaucracy.

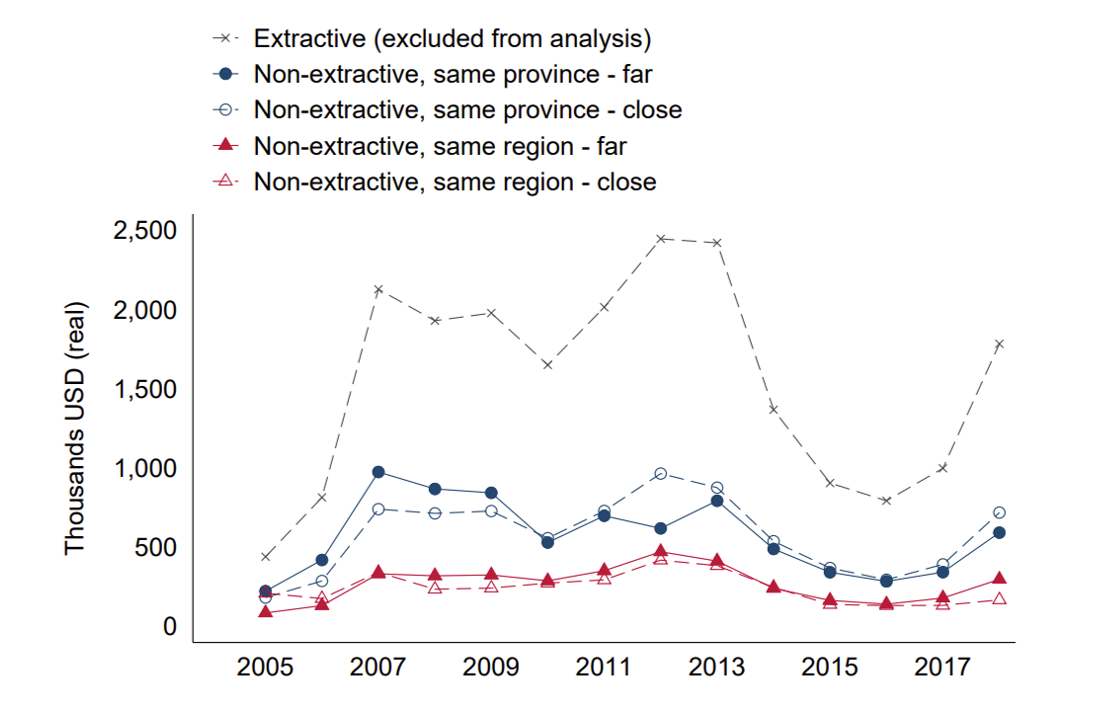

Second, we exploit variation in windfall intensity across time and space. Exposure to windfalls is predetermined by a fixed rule from the central government, which did not change over time. This rule redistributes natural resource revenues to non-extractive district municipalities (included in the analysis) within the same higher-level jurisdictional boundaries as extractive districts (excluded from the analysis). At the beginning of the study period, Peru had 1830 districts within 196 provinces, within 25 regions. From the total natural resource tax revenues collected in a region, 10% goes directly to the extractive district, 25% to all municipalities located in the province, 40% to all municipalities in the region, and 25% to the regional government. Over time variation in windfalls in non-extractive districts arises from shocks to commodity extraction in the same province and region, but in a different district (extractive). Consequently, the intensity of resource windfalls depends on jurisdictional rather than spatial proximity to extractive activities, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Transfers allocated based on jurisdictional rather than spatial proximity to extractive activities

Notes: `Far' denotes districts that are located at or above the median distance to the closest mining activity, and `Close' denotes those that are located below. The sample is restricted to mining regions.

Third, we construct a novel dataset to trace transaction flows within districts. We create a panel dataset spanning 2006–2018 combining administrative records for 1,600 district municipalities, matched to a repeated cross-section of 700,000 individuals and 200,000 microenterprises interviewed in the national household survey.

Transfers to local governments stimulated local economic development

We first show that nearly all windfalls convert to public expenditures, with spending shifting toward capital investment (USD 0.80 per dollar transferred), aligning with the ring-fencing of funds for this purpose. These windfalls flow into local economies through two main channels: the local procurement of goods and services, and the employment of municipal personnel to execute public infrastructure projects. In a case where public expenditures tripled due to resource windfalls, local governments initiated more than three times as many productive infrastructure projects and over 1.7 times as many projects to promote social capital.

Additionally, municipal human resources nearly doubled, primarily driven by low-skilled workers with fixed-term contracts hired for these projects.

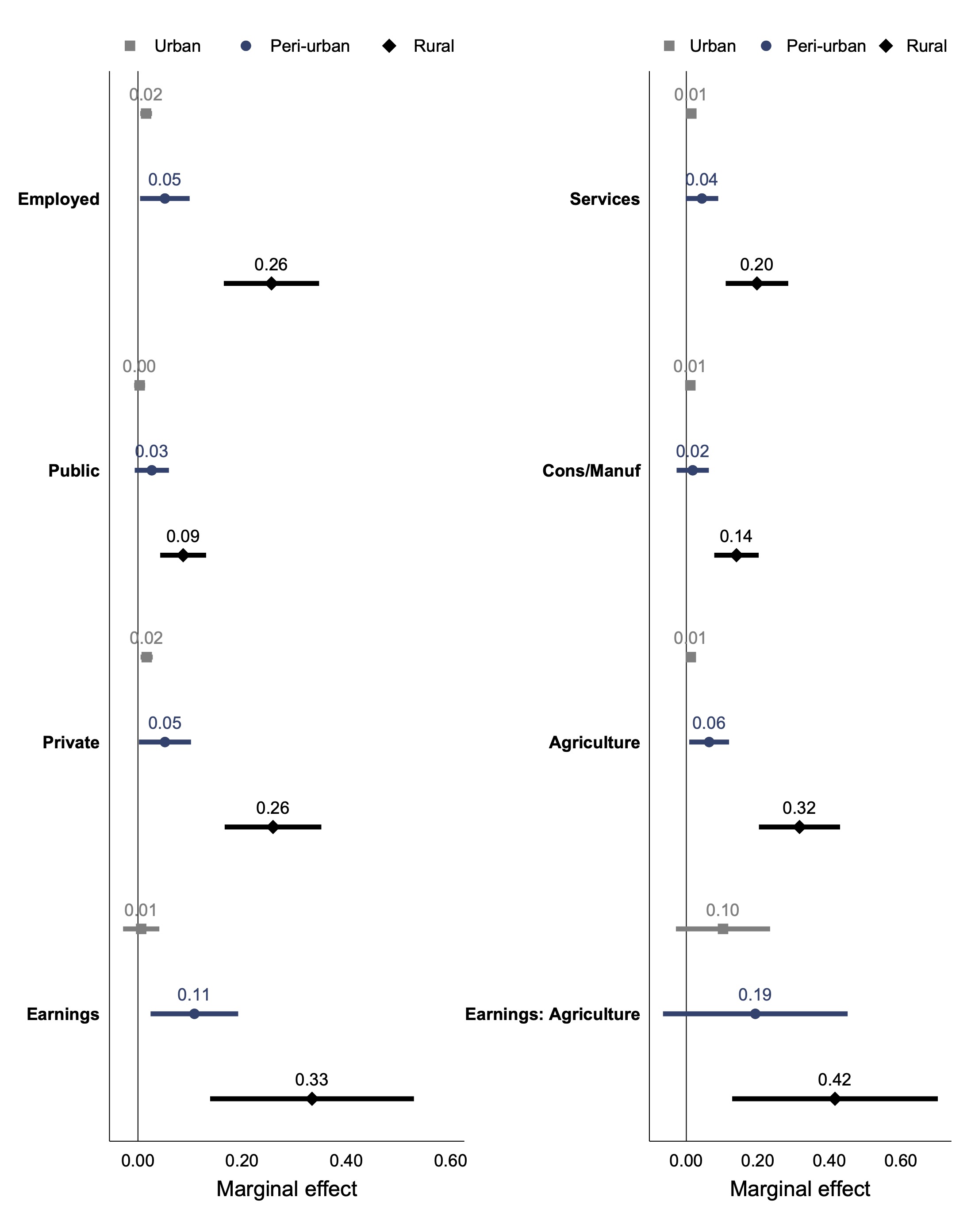

We next investigate how local economies absorbed such a large shock to aggregate demand. Notably, inactivity is high in this context, with only around 65% of the labour force active at the beginning of the study period. We find an increase by 6.0 percentage points (ppts) on the likelihood of employment relative to inactivity, with similar impacts across the public and private sectors, and a decrease by 1.0 ppts on the likelihood of informal employment. Employment increased across all sectors, including services, construction, manufacturing, and agriculture, and for different occupations (i.e. employer, wage-employed, self-employed, and unpaid worker in home business). We further estimate an earnings elasticity of 0.05, with a larger magnitude in the agricultural sector (0.3).

We also find a boost in microenterprise activity, with a revenue elasticity of 0.07 for non-agricultural businesses and 0.33 for agricultural businesses, along with a rise in labour productivity. Revenue gains are mainly driven by entrepreneurs working on their own account and by farmers reliant on household labour. Non-agricultural enterprises became 2.0 ppts more likely to own business premises, while the elasticity of landholdings for agricultural enterprises reached 0.24.

Notably, the agricultural sector benefited significantly from the windfalls, despite not being a sector that typically serves municipalities. This influx of resources helped close gaps between urban and rural areas, with rural households reaping the greatest benefits.

Figure 2 shows a clear gradient in the effects across urban, peri-urban and rural households. In rural areas, the impact on employment stands at 26.0 ppts (compared to 6.0 ppts for all areas), and the earnings elasticity rose to 0.33 (compared to 0.05).

These rural households experienced real-term income and consumption gains. We estimate an income elasticity of 0.60 and a consumption elasticity of 0.12, driven by increased spending on food and rent. Importantly, we find that the likelihood of falling below the local poverty line dropped by 11.0 ppts.

All effects are real rather than nominal, as monetary values are adjusted using regional deflators. Moreover, we find no strong evidence of inflationary pressures within districts when examining wages and food prices, in line with significant slack in these local economies.

Figure 2: Greater effects in rural areas, closing spatial gaps

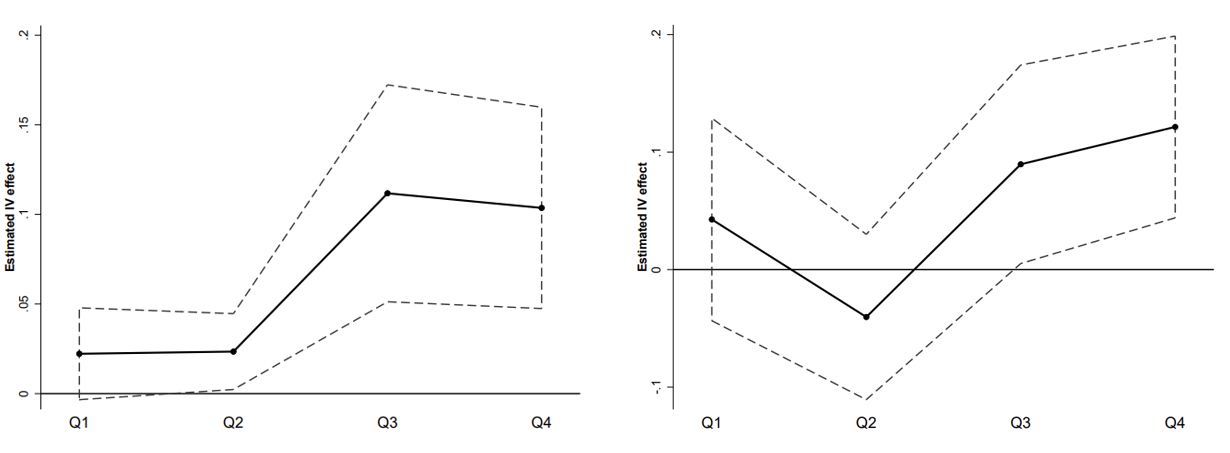

As part of our broader set of robustness checks, we explore whether our results could be explained by proximity to extractive activities. In Figure 3 we show that, if anything, the effects are concentrated in areas further away from extractive activities. Moreover, we investigate if differences in characteristics across districts that receive high or low resource windfalls could be driving the results. For this, we exploit the fact that the redistribution formula creates a discontinuity in resource windfalls received by contiguous district municipalities along a region’s border. Adjacent municipalities in different regions, looking otherwise the same, can receive substantially different amounts of transfers depending on the commodity produced in their region and the shocks these receive. The results are robust, and even greater in magnitude, when comparing districts across the same boundary.

Figure 3: Effects on employment and earnings not driven by proximity to extractive activities

Notes: Q1 is at or below 20 km; Q2 spans {20-35] km; Q3 spans {35-65] km; and Q4 is above 65 km from the closest extractive activity.

Welfare implications of public investment in Peru

Finding effects in industries that not necessarily serve municipalities provide evidence of positive multiplier effects. A back-of-the-envelope calculation reveals that for every dollar transferred to municipalities, an additional USD 2.79 - 3.86 were generated in the local economy.

Several positive effects of resource windfalls persist over time, particularly those on earnings and labour productivity in non-agricultural enterprises, along with the reduction in poverty.

The spatial distribution of benefits is crucial for welfare, especially if we place greater value on expanding the budget sets of poorer households. General equilibrium effects show that the benefits primarily reached the poorest residents living in disadvantaged rural areas.

Our study is highly relevant for countries rich in mineral resources, as the windfalls we examine primarily stem from mining. The transition to a low-carbon economy will shift demand away from coal, oil, and gas toward the minerals required for green technologies. So, how can the many low- and middle-income countries endowed with these critical minerals best leverage their resources to foster economic development? Our findings underscore the importance of redistribution, demonstrating how the public sector can channel resource rents to poorer areas and support more inclusive growth.

References

Bancalari A (2024), "The unintended consequences of infrastructure development," Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Bancalari A, and JP Rud (2024), "Resource windfalls, public expenditures, and local economies," IZA Discussion Paper No. 17464.

Caselli F, and G Michaels (2013), "Do oil windfalls improve living standards? Evidence from Brazil," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5(1): 208–238.

Chodorow-Reich G (2019), "Geographic cross-sectional fiscal spending multipliers: What have we learned?" American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 11(2): 1–34.

Cunha J, G De Giorgi, and S Jayachandran (2019), "The price effects of cash versus in-kind transfers," Review of Economic Studies 86(1): 240–281.

Corbi R, E Papaioannou, and P Surico (2018), "Regional transfer multipliers," The Review of Economic Studies 86(5): 1901–1934.

Egger D, J Haushofer, E Miguel, P Niehaus, and M Walker (2022), "General equilibrium effects of cash transfers: Experimental evidence from Kenya," Econometrica 90(6): 2603–2643.

Jaimovich E, and JP Rud (2014), "Excessive public employment and rent-seeking traps," Journal of Development Economics 106: 144–155.

Keynes JM (1936), The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Macmillan.

Walker M, N Shah, E Miguel, D Egger, F S Soliman, and T Graff (2024), "Slack and economic development," NBER Working Paper No. 33055.