Evidence from Kenya shows how cash transfers in imperfect markets lead businesses to capture some of the benefits by raising prices, ultimately at the expense of transfer recipients.

Studying market impacts is crucial

There is mounting empirical evidence regarding the positive and persistent effects of cash-based assistance on direct recipients and, as a result, cash transfer programmes are rapidly expanding in developing countries (Gentilini 2024).

However, research on the effects of cash transfers on local businesses and markets remains limited, particularly for small but regular transfers that reach billions of beneficiaries through social and humanitarian assistance (see Egger et al. 2022 for insights on large one-time grants). This gap in previous research is problematic for at least two reasons.

First, cash transfer programmes can encourage business creation and stimulate existing businesses, generating positive impacts that extend beyond direct recipients. Considering these indirect or “spillover” effects on non-recipient households are essential to understand the full impact of cash transfers (see e.g. Angelucci and De Giorgi 2009, D’Aoust et al. 2018, Egger et al. 2022).

Second, the ultimate impact of cash transfers on recipients depends on how businesses respond to the demand surge, which in turn is shaped by the competitive structure of the market.

In highly competitive markets, transfer recipients are expected to capture the full transfer benefits. Beyond a possible adjustment period in the short run, prices should remain stable, and businesses make no excess profit.

However, markets are rarely perfectly competitive, especially in rural economies, which are often characterised by high transportation costs from poor infrastructure, hidden pricing, credit constraints, and fixed costs that prevent economies of scale. In imperfect markets, businesses may be able to set their prices above marginal cost and, as a consequence, direct recipients may not capture the full benefits of the cash transfers.

Humanitarian cash transfers to refugees in Kenya

Our research (Delius and Sterck 2024) documents the market and business impacts of a large-scale programme of restricted cash transfers implemented by the World Food Programme (WFP) in Kenya. In 2018, about 400,000 refugees living in camps or settlements in Kenya were receiving monthly digital transfers worth three to thirteen dollars. Recipients could only use the cash to purchase food items at licensed shops.

Similar restricted cash transfer programmes are widely used, often taking the form of digital cash transfers or vouchers (Siu et al. 2023). In 2020, 29% of all cash-based humanitarian assistance—almost $2 billion—was provided with restrictions on how and where transfers could be spent (Girling and Urquhart 2021). In the US, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) distributes electronic benefits restricted to food purchases, reaching 40 million Americans in 2018 with total benefits amounting to $61 billion. Similar programmes are also employed to encourage sustainable consumption, such as Belgium’s EcoCheque programme, which promotes eco-friendly purchases.

In our study, we exploit quasi-random variation in the allocation of WFP licenses for businesses to accept payments from the digital transfers, to assess impacts of cash transfers on licensed businesses. The licenses were allocated following a competitive process in two steps. First, applicants had to fill an application form, in which they had to describe the characteristics of their businesses and commit to certain standards of conduct. Second, a multi-stakeholder committee with representatives from humanitarian organisations and the Government of Kenya allocated the licenses based on the data in the application forms. They deliberately selected a diversity of shop owners in terms of gender, origin, and location of their shops. To estimate the impact of gaining access to the programme on businesses, we match successful and unsuccessful applicants using data from the application process.

While matching methods often receive bad press in economics, we believe our study provides a good example of a setting in which matching methods can be credibly used as

- We have a clear understanding of the licensing process and access to all relevant data used by the selection committee.

- Placebo tests confirm that treatment status is uncorrelated with predetermined characteristics that serve as proxies for entrepreneurial ability.

- Proxies for business size and capacity are insignificant in the propensity score estimates, indicating that the selection committee did not systematically select the most (or least) successful businesses.

Therefore, the ‘unconfoundedness’ assumption is both statistically and contextually plausible (McKenzie 2021), so we expect experimental and matching methods to yield similar, unbiased impact estimates (Heckman et al. 1997, Dehejia and Wahba 2002, Diaz and Handa 2006).

Businesses massively benefit from transfers

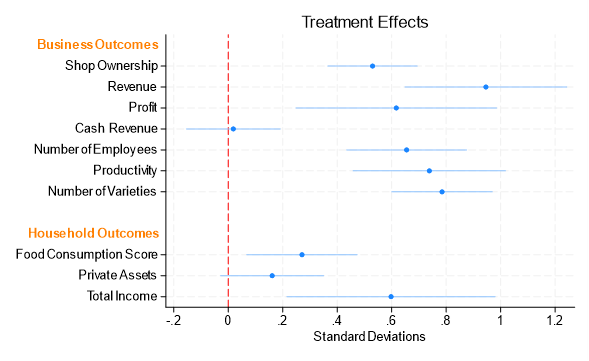

We find that license recipients benefit significantly from the cash transfer programme (Figure 1). Licensed businesses see average monthly revenues that are $3,784 higher than those of unlicensed businesses (+175%). The impact on profits is also substantial: licensees report average monthly profits $685 higher than unlicensed applicants (+154%). In addition, licensed businesses employ more workers, have higher productivity, sell a broader range of products, and their households enjoy higher incomes, better diets, and more assets compared to the control group.

These large effects are partly explained by the fact that successful applicants are more likely to still operate a business (+24 percentage points), but also that they are much more successful than unlicensed businesses. For businesses that would have existed regardless of the cash transfer programme, we estimate that having a license raises monthly profits by over $526 (+86%)—a large impact equivalent to 18 times the average monthly wage of employees ($29) and 39 times the average monthly food assistance per refugee ($13).

Figure 1: Treatment impact of licenses in standard deviations

Transfers generate a two-tier market with distinct pricing

The large profits observed in the food retail sector provide evidence of market imperfections, which are magnified by the digital cash transfer programme. Using data from a household survey, we find that households are charged 16 to 30% higher prices for purchases paid with digital cash transfers compared to purchases with hard cash.

Such a (additional) markup is substantial and expected to have large negative repercussions on refugee welfare. The digital cash transfer programme generated two parallel markets. The market for hard cash transactions is relatively competitive, with about 1,400 shops offering low prices to attract consumers. By contrast, the new market for digital cash transfers is restricted to 252 licensed vendors which can charge higher prices. Due to market imperfections, including the restrictions on the number of licensed retailers and high transportation costs, licensed businesses capture part of the benefits of the cash transfer programme, at the expense of recipients.

Policy implications: Address market imperfections to maximise impacts on recipients

These findings underscore the importance of understanding the impacts of cash transfers on markets and businesses.

Organisations implementing cash transfer programmes should identify and address market imperfections to limit rent-seeking and maximise positive impacts on cash transfer recipients.

They should consider market imperfections that exist before the implementation of the cash transfer as well as imperfections that may be introduced through the design of the programme. For instance, our findings illustrate the risks and drawbacks of restricted cash transfers, which in practice may favour the establishment of a parallel market with reduced competition and higher prices.

References

Angelucci, M, and G De Giorgi (2009), “Indirect effects of an aid program: How do cash transfers affect ineligibles’ consumption?” American Economic Review, 99(1): 486–508.

D’Aoust, O, O Sterck, and P Verwimp (2018), “Who benefited from Burundi’s demobilization program?” The World Bank Economic Review, 32(2): 357–382.

Delius, A, and O Sterck (2024), “Cash transfers and micro-enterprise performance: Theory and quasi-experimental evidence from Kenya,” Journal of Development Economics, 167: 103232.

Dehejia, R H, and S Wahba (2002), “Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(1): 151–161.

Diaz, J J, and S Handa (2006), “An assessment of propensity score matching as a nonexperimental impact estimator: Evidence from Mexico’s PROGRESA program,” Journal of Human Resources, XLI(2): 319–345.

Egger, D, J Haushofer, E Miguel, P Niehaus, and M W Walker (2022), “General equilibrium effects of cash transfers: Experimental evidence from Kenya,” Econometrica, 90(6): 2603–2643.

Gentilini, U (2024), Timely Cash: Lessons from 2,500 Years of Giving People Money, Oxford University Press.

Girling, F, and A Urquhart (2021), Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2021, Development Initiatives, Bristol.

Heckman, J J, H Ichimura, and P Todd (1997), “Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training programme,” Review of Economic Studies, 64(4): 605–654.

McKenzie, D (2021b), “What do you need to do to make a matching estimator convincing? Rhetorical vs statistical checks,” The World Bank Development Impact Blog. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/impactevaluations/what-do-you-need-do-make-matching-estimator-convincing-rhetorical-vs-statistical.

Siu, J, O Sterck, and C Rodgers (2023), “The freedom to choose: Theory and quasi-experimental evidence on cash transfer restrictions,” Journal of Development Economics, 161: 103027.