A transfer programme in Bangladesh led to sustained consumption increases and reduced poverty four years post-programme, but design and context mattered.

Cash and food transfer programmes in low- and middle-income countries have been shown to be highly effective in increasing household consumption and reducing household poverty in the short term (Bastagli et al. 2016, Hidrobo et al. 2018, Borga and D’Ambrosio 2021, Ravallion 2016). But evidence on whether they sustain longer-term impacts after programmes end is more mixed. Some studies of transfer programmes show significant sustained medium- to long-term impacts on consumption and poverty (e.g. Carneiro et al. 2021, Stoeffler et al. 2020, Macours et al. 2022), but others show effects fading out (e.g. Handa et al. 2019, Cahyadi et al. 2020, Haushofer and Shapiro 2018 ). Some interventions combining transfers with additional components such as cash “plus” programmes or multi-faceted graduation models sustain impacts on consumption four to ten years post-intervention (Bandiera et al. 2017, Banerjee et al. 2022), while others do not (Brune et al. 2022).

The mixed evidence on medium- to long-term impacts of transfer programmes on consumption and poverty leaves several knowledge gaps, notably on the roles played by (1) transfer modality (e.g. cash vs. food), (2) inclusion of complementary programming (e.g. trainings), and (3) contextual factors.

In our research (Ahmed et al. forthcoming), we assess whether a two-year transfer programme implemented in Bangladesh had sustained impacts on consumption and poverty four years after it ended – focusing on whether sustained impacts depended on transfer modality, complementary programming, and context.

Providing transfers and behaviour change communication to mothers of young children in rural Bangladesh

The intervention – the Transfer Modality Research Initiative (TMRI) – was implemented by the World Food Programme in two regions of Bangladesh: Rangpur division (hereafter “North”), and Barisal and Khulna divisions (hereafter “South”). The programme provided mothers of young children in poor rural households with monthly food or equal-value cash transfers (worth 1500 taka or about 25% of households’ pre-intervention monthly income), with or without a complementary nutrition behaviour change communication (BCC) component. This component involved three activities:

(1) Weekly interactive group trainings led by a community nutrition worker – some with only target mothers and some also inviting other family members.

(2) Twice-a-month home visits.

(3) Monthly group meetings with influential community leaders.

The BCC content focused on promoting knowledge and adoption of recommended practices for young children’s nutrition and health.

Understanding the causal effect of the intervention at endline and four years post programme

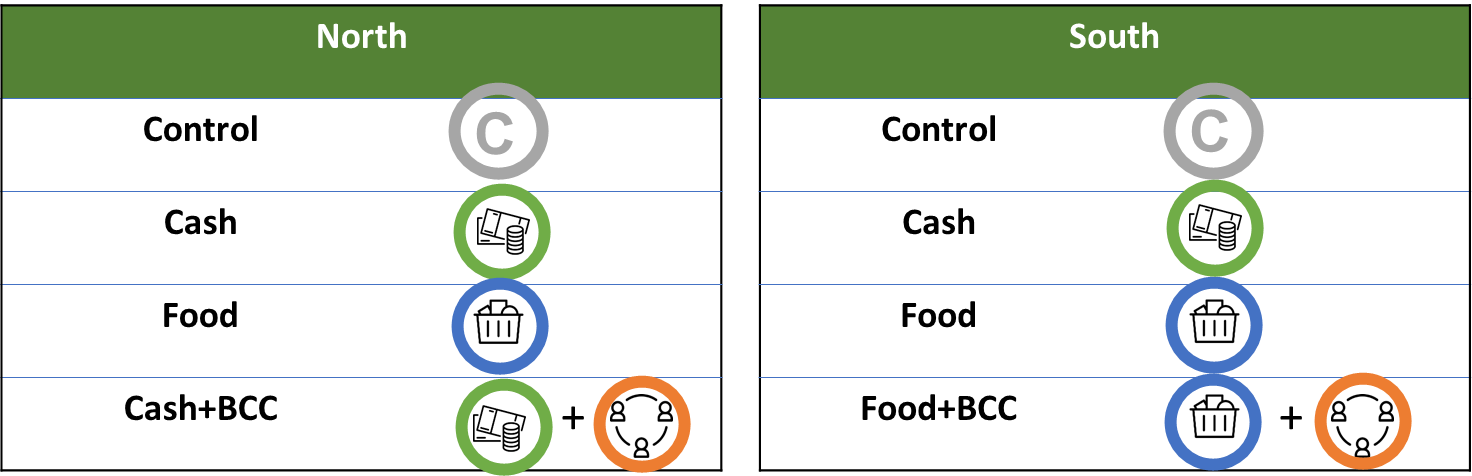

Between May 2012 and April 2014, the intervention was implemented in each of the two regions as a cluster-randomised control trial (RCT). The intervention arms included in our study are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Intervention arms by region

Using data collected in three rounds of surveys – baseline (April-May 2012), endline (April 2014), and four-years post-programme (April 2018) – we assessed causal impacts of TMRI’s treatment arms on household consumption and poverty at endline and four-years post-programme, in each region. Comparing impacts across arms and regions allows us to understand the role of design features and context in sustaining impacts: cash versus food, transfers with BCC versus those without BCC, and North versus South.

The impacts of the transfer programme in Bangladesh on consumption and poverty

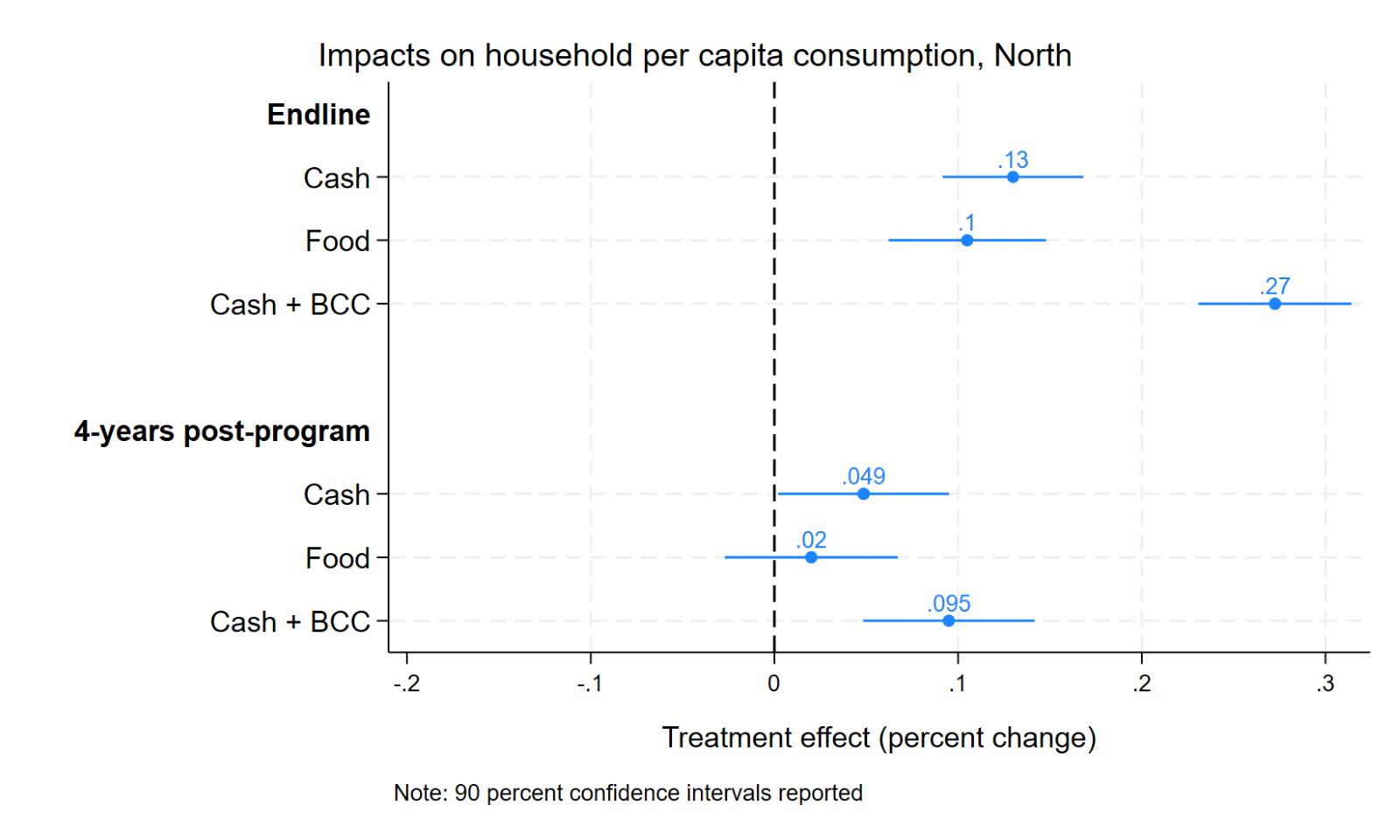

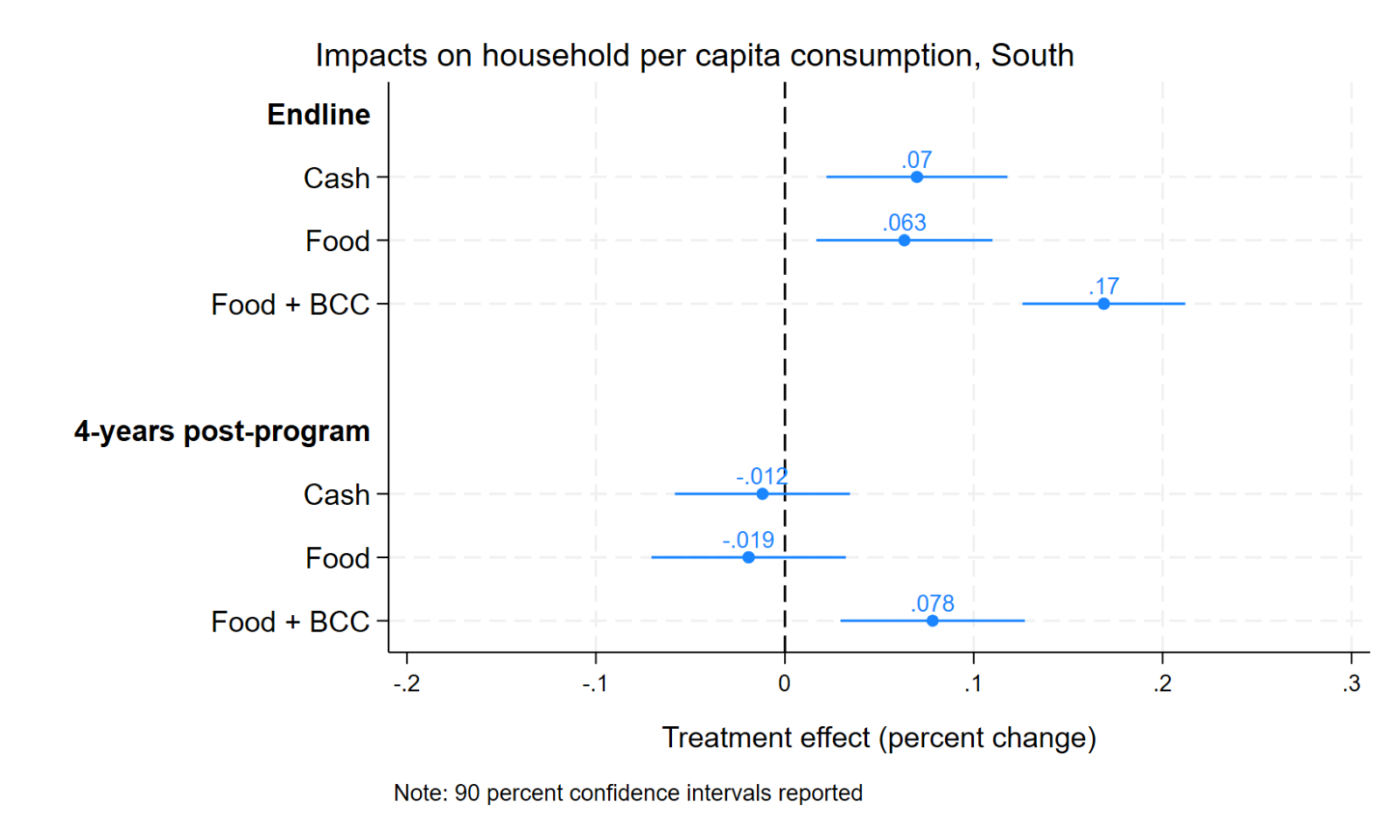

We find that, during the implementation of TMRI, all treatment arms in each region improved average consumption, with significantly larger impacts in the arms with BCC . However, four years post-programme, sustainability of impacts depended on transfer modality, complementary programming, and context. In particular, the initial beneficial impacts of food transfers alone did not persist in either region four years post-programme. The impacts of cash transfers alone persisted in the North but not in the South. In both regions, the arms combining transfers with the BCC led to sustained improvements in consumption, although impacts were smaller than at endline.

Figure 2: Impacts on consumption at endline and four-years post programme

We find a similar pattern of impacts on poverty. While all TMRI treatments in both regions led to significant reductions in poverty during the programme, some but not all led to sustained reductions four years post-programme. Four years after TMRI ended, food transfers alone had no significant sustained impacts on poverty in either region. In the North, significant reductions in poverty were sustained from cash transfers with or without BCC. In the South, cash transfers alone did not have significant sustained impacts (although they did in the North) and Food+BCC had limited impacts.

Potential mechanisms behind the patterns of sustained impacts

In the North, we found that Cash and Cash+BCC arms led to sustained impacts on consumption and poverty four years post-intervention. Impacts were stronger from Cash+BCC, driven by sustained increases in livestock, savings, homestead production, agricultural labour supply, and women’s psychosocial wellbeing. The wider range of impacts from adding BCC may have resulted from women being better informed about the importance of nutrition, shifting their preferences around nutritious foods and investing in activities related to livestock rearing and homestead gardening. We found no impacts of Food in the North on consumption or poverty, nor on potential pathways, at four years post-programme.

In the South, results were more muted. At four years post-programme, Food+BCC showed significant increases in consumption but limited reductions in poverty. Unlike in the North, improved consumption did not translate to reduced poverty in the South, likely due to differences in the consumption distribution across regions. Sustained impacts from Food+BCC on consumption were in part driven by sustained increases in homestead production and labour supply, but not asset holdings. We did not find sustained impacts of Cash or Food on consumption or poverty, nor on potential pathways. The lack of sustained impact from Cash in the South, unlike in the North, is likely due to differences in context – including different income distributions and levels of poverty, different agroecology and investment opportunities, and differences in the availability of other private and public transfers – all of which allowed the control group in the South to catch up to the Cash arm.

Implications for designing transfer programmes

In terms of what shapes sustained impacts from transfer programmes, our results indicate that (1) modality matters, given that the Cash arm was more likely than the equal-value Food arm in the North to lead to sustained impacts on consumption, poverty, and potential mechanisms; (2) complementary activities matter, given that the addition of BCC led to larger sustained impacts on consumption across both regions; (3) context matters, given that the same Cash treatment had weaker impacts on consumption and poverty in the South than the North.

Our findings provide insights into the mixed literature on whether cash transfer programmes have sustained impacts. First, the finding that cash on its own can lead to sustained impacts on consumption and poverty, but that it depends on context, is consistent with mixed results in the literature on the medium- to long-term impacts of cash transfers. Second, the finding that programme design matters may help to explain the differences across studies. We find that adding more complementary components to cash can lead to larger sustained impacts, consistent with other studies that show that the provision of complementary components can be beneficial (Banerjee et al. 2022, Bossuroy et al. 2022, Macours et al. 2022, Sedlmayr et al. 2020). More broadly, our results highlight that combining cash transfers with complementary programming may be promising for sustained improvements in consumption and poverty reduction.

References

Bandiera, O, R Burgess, N Das, S Gulesci, I Rasul, and M Sulaiman (2017), “Labor markets and poverty in village economies,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(2): 811–870.

Banerjee, A, E Duflo, and G Sharma (2021), “Long-term effects of the Targeting the Ultra Poor Program,” American Economic Review: Insights, 3(4): 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20200667.

Banerjee, A, D Karlan, R Osei, H Trachtman, and C Udry (2022), “Unpacking a multi-faceted program to build sustainable income for the very poor,” Journal of Development Economics, 155: 102781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102781.

Bastagli, F, J Hagen-Zanker, L Harman, V Barca, G Sturge, T Schmidt, and L Pellerano (2016), “Cash transfers: What does the evidence say? A rigorous review of programme impact and of the role of design and implementation features.”

Borga, L G, and C D’Ambrosio (2021), “Social protection and multidimensional poverty: Lessons from Ethiopia, India, and Peru,” World Development, 147: 105634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105634.

Bossuroy, T, M Goldstein, B Karimou, D Karlan, H Kazianga, W Parienté, P Premand, C C Thomas, C Udry, J Vaillant, and K A Wright (2022), “Tackling psychosocial and capital constraints to alleviate poverty,” Nature, 605(7909): 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04647-8.

Brune, L, D Karlan, S Kurdi, and C Udry (2022), “Social protection amidst social upheaval: Examining the impact of a multi-faceted program for ultra-poor households in Yemen,” Journal of Development Economics, 155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102780.

Carneiro, P, L Kraftman, G Mason, L Moore, I Rasul, and M Scott (2021), “The impacts of a multifaceted prenatal intervention on human capital accumulation in early life,” American Economic Review, 111(8): 2506–2549.

Cahyadi, N, R Hanna, B A Olken, R A Prima, E Satriawan, and E Syamsulhakim (2020), “Cumulative impacts of conditional cash transfer programs: Experimental evidence from Indonesia,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 12(4): 88–110.

Handa, S, G Tembo, L Natali, G Angeles, and G Spektor (2019), “In search of the holy grail: Can unconditional cash transfers graduate households out of poverty in Zambia?”

Haushofer, J, and J Shapiro (2018), “The long-term impact of unconditional cash transfers: Experimental evidence from Kenya,” Busara Center for Behavioral Economics, Nairobi, Kenya.

Hidrobo, M, J Hoddinott, N Kumar, and M Olivier (2018), “Social protection, food security, and asset formation,” World Development, 101: 88–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.08.014.

Macours, K, P Premand, and R Vakis (2022), “Transfers, diversification and household risk strategies: Can productive safety nets help households manage climatic variability?” The Economic Journal, 132(647): 2438–2470. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueac018.

Ravallion, M (2016), The Economics of Poverty: History, Measurement and Policy, Oxford University Press.

Sedlmayr, R, A Shah, and M Sulaiman (2020), “Cash-plus: Poverty impacts of alternative transfer-based approaches,” Journal of Development Economics, 144: 102418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102418.

Stoeffler, Q, B Mills, and P Premand (2020), “Poor households’ productive investments of cash transfers: Quasi-experimental evidence from Niger,” Journal of African Economies, 29(1): 63–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejz017.