Colonial segregation policies in Mexico City entrenched divisions between Spaniards and indigenous communities, shaping modern economic inequalities because of weak property rights, unequal provision of public goods and enduring social stigma.

As the work of this year’s Nobel Laureates has shown, history significantly impacts current economic development outcomes. In Latin America and other regions with a colonial past, colonial legacies persist in dimensions like language, legal systems, religious practices, and social institutions. Yet, one of the less apparent legacies of colonialism lies beneath our feet: the value of urban land.

Historical events shape cities’ internal structures, affecting the layout and value of neighbourhoods. Understanding how and why these influences persist in modern life is essential. In our research, we explore the long-term effects of a Spanish colonial policy that segregated Indigenous communities into designated areas known as pueblos de indios (or “Indian villages”) and assess how this policy has affected Mexico City’s economic and spatial landscape centuries later.

The colonial roots of segregation in Mexico

When the Spanish arrived in Mesoamerica, they encountered civilisations ranging from small, stateless communities to vast empires, with the Nahua or Aztec empire at the centre of Mexico-Tenochtitlán. Beyond the conquest’s immediate violence and demographic toll, the Spanish reorganisation of land and society profoundly affected Mexico’s urban landscape.

In 1538, the Spanish Crown established repúblicas de indios (“Indigenous republics”), as semi-autonomous entities meant to separate Indigenous people from Spanish settlers. These republics managed their own tax collection, public goods provision, and records, but they also enforced physical segregation through laws mandating minimum distances between Indigenous and Spanish settlements. Scholars debate the reasons for this separation; some argue that it was to protect Indigenous people from disease, while others view it as a colonial strategy to maintain social order and racial hierarchy.

The pueblos de indios became the designated spaces for Indigenous communities, with specific land rights typically extending 420 to 500 metres from a central plaza, which included a church and small agricultural plots. Over time, two types of pueblos developed: isolated pueblos that had minimal interaction with Spanish and mixed-race communities and more integrated pueblos closer to colonial cities. This integration allowed Indigenous residents to buy and sell land with mestizos, peninsulares (Iberian-born Spaniards), and criollos (American-born Spaniards). In some cases, Indigenous people sold land to other ethnic groups seeking affordable housing.

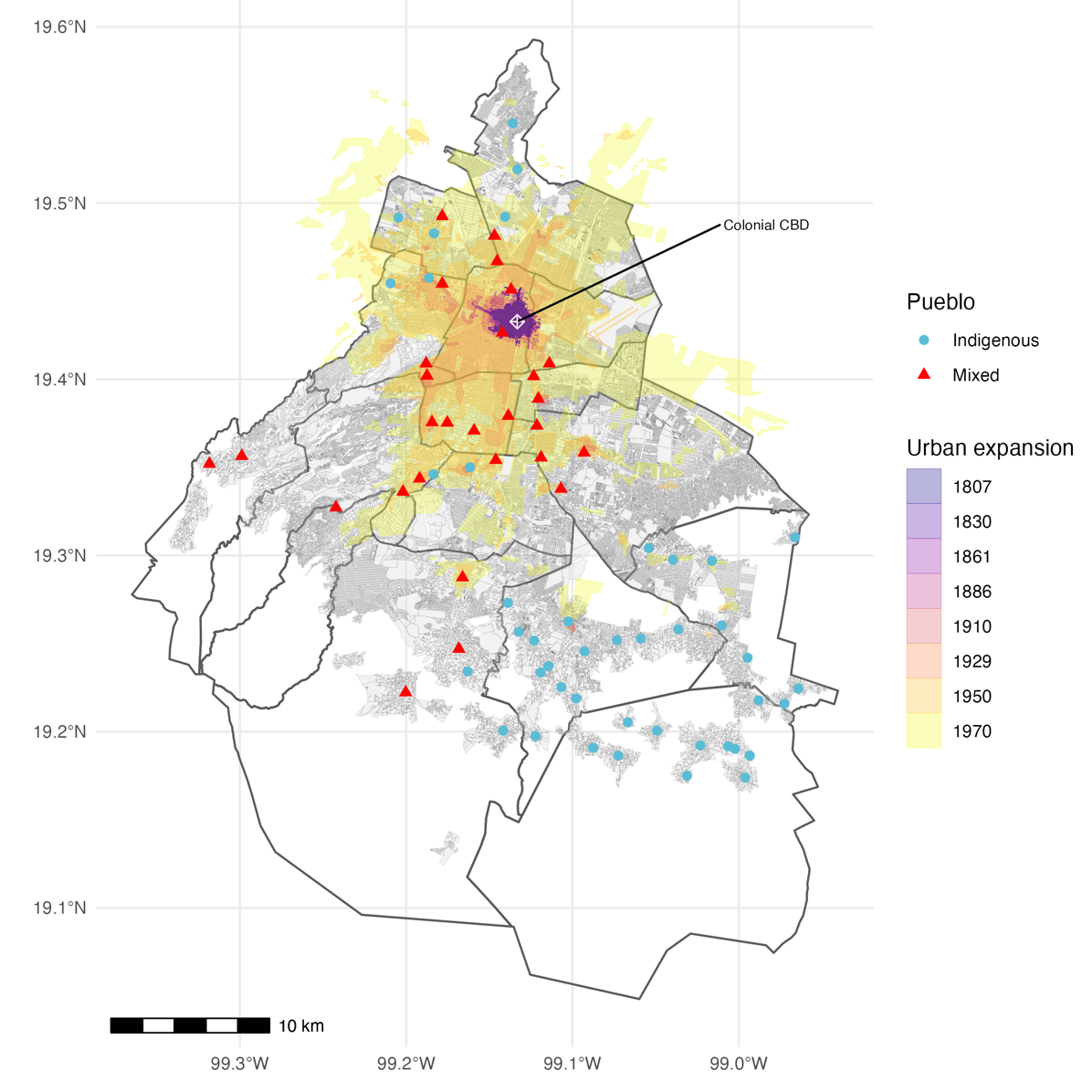

Thanks to the work of historian Dorothy Tanck de Estrada, we can map the location of thousands of pueblos across Mexico. 71 pueblos, out of more than 4,000 from the early 19th century, lie within what is now Mexico City (see Figure 1). This mapping provides a foundation for examining the long-term economic effects of these historical boundaries.

Figure 1: Pueblos’ location in Mexico City

Notes: The locations of the pueblos de indios are based on Tanck de Estrada (2005). Turquoise dots indicate the Indigenous pueblos and red triangles indicate the mixed pueblos. The thick gray lines represent the boundaries of current-day municipalities of Mexico City. The grey areas represent current-day city blocks. The white symbol represents the colonial central business district (CBD). Historical estimates of urban expansion coloured as per Angel et al. (2012).

Measuring the legacy of segregation in Mexico City

To investigate the enduring impact of colonial segregation, we used the historical location of pueblos and their boundaries. We then cross-referenced these locations with contemporary cadastral land values from Mexico City’s Treasury, based on official appraisals that consider factors such as location, land use, and surface area. To assess the impact of pueblos de indios on land values, we compared properties within and outside these historical boundaries.

This comparison isn’t straightforward; factors like soil quality, infrastructure, and neighbourhood amenities vary widely across the city. Comparing land near a former pueblo like Tacubaya with land in Polanco, for instance, would not yield meaningful insights due to substantial socioeconomic differences.

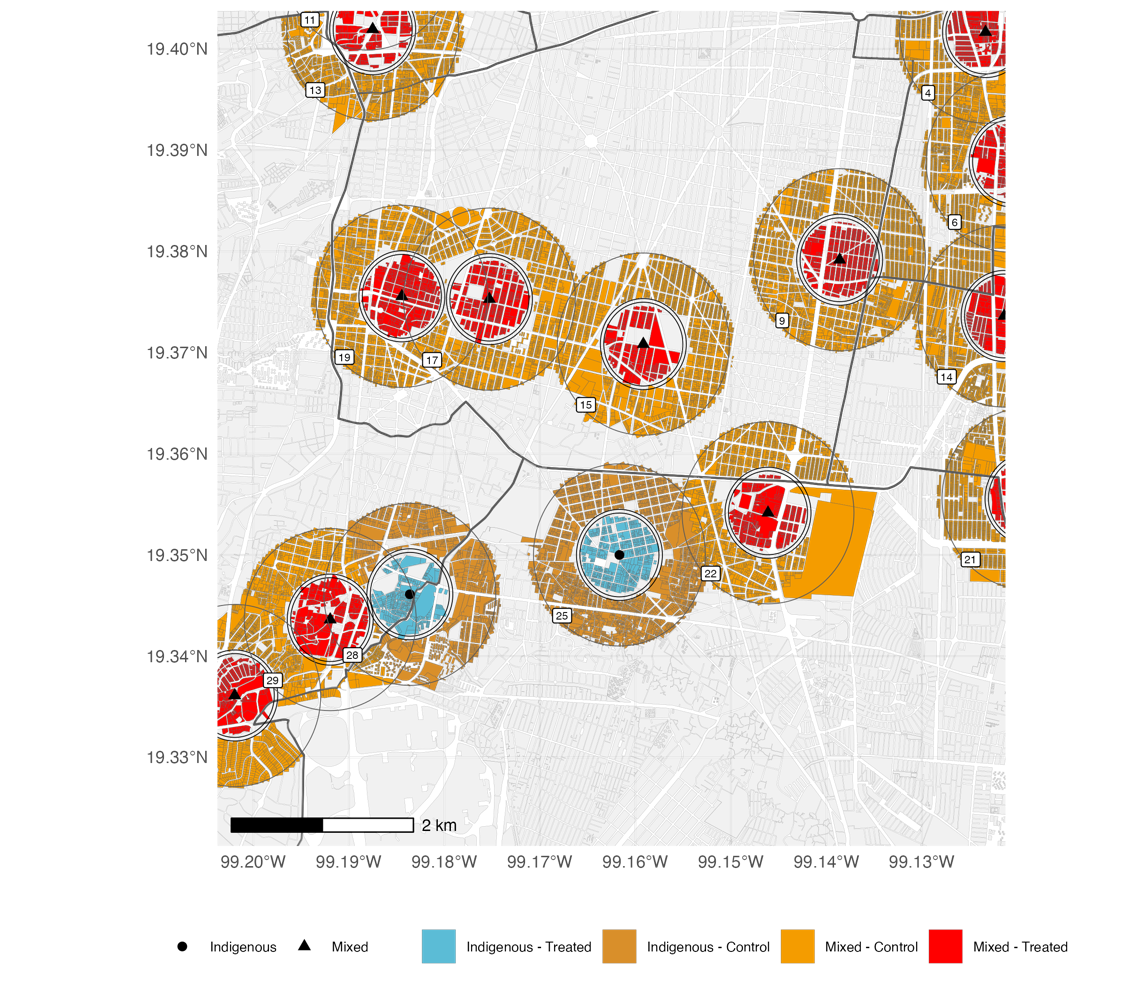

Since pueblos were typically defined with a radius of 420 to 500 metres, we used these boundaries to create a more controlled comparison. We examined land values within 415 metres of the pueblo centre against plots 505 metres to one kilometre away. By focusing on plots close to each other, we controlled for factors like transportation access and local amenities, ensuring that any difference in value was primarily due to proximity to a pueblo boundary (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Identification illustration – pueblo locations and fuzzy boundaries

Notes: This map illustrates the two treatment groups and their respective control groups in our spatial RDD framework, zooming in on the Benito Juárez and Coyoacán municipalities. The thick grey lines represent the municipality boundaries. The grey areas represent the land plots. Buffers of three different radii encircle each pueblo: 420 metres, 500 metres, and one kilometre. Land plots within blue and red circles lie within 500 metres from the center of the nearest pueblo de indios. Orange plots lie 500 to 1000 metres away from the nearest pueblo de indios center. We exclude plots outside these areas.

Persistent land value penalties for segregated pueblos

Our findings reveal a substantial land value penalty associated with pueblos de indios. Land within these historical boundaries shows consistently lower values than land just outside.

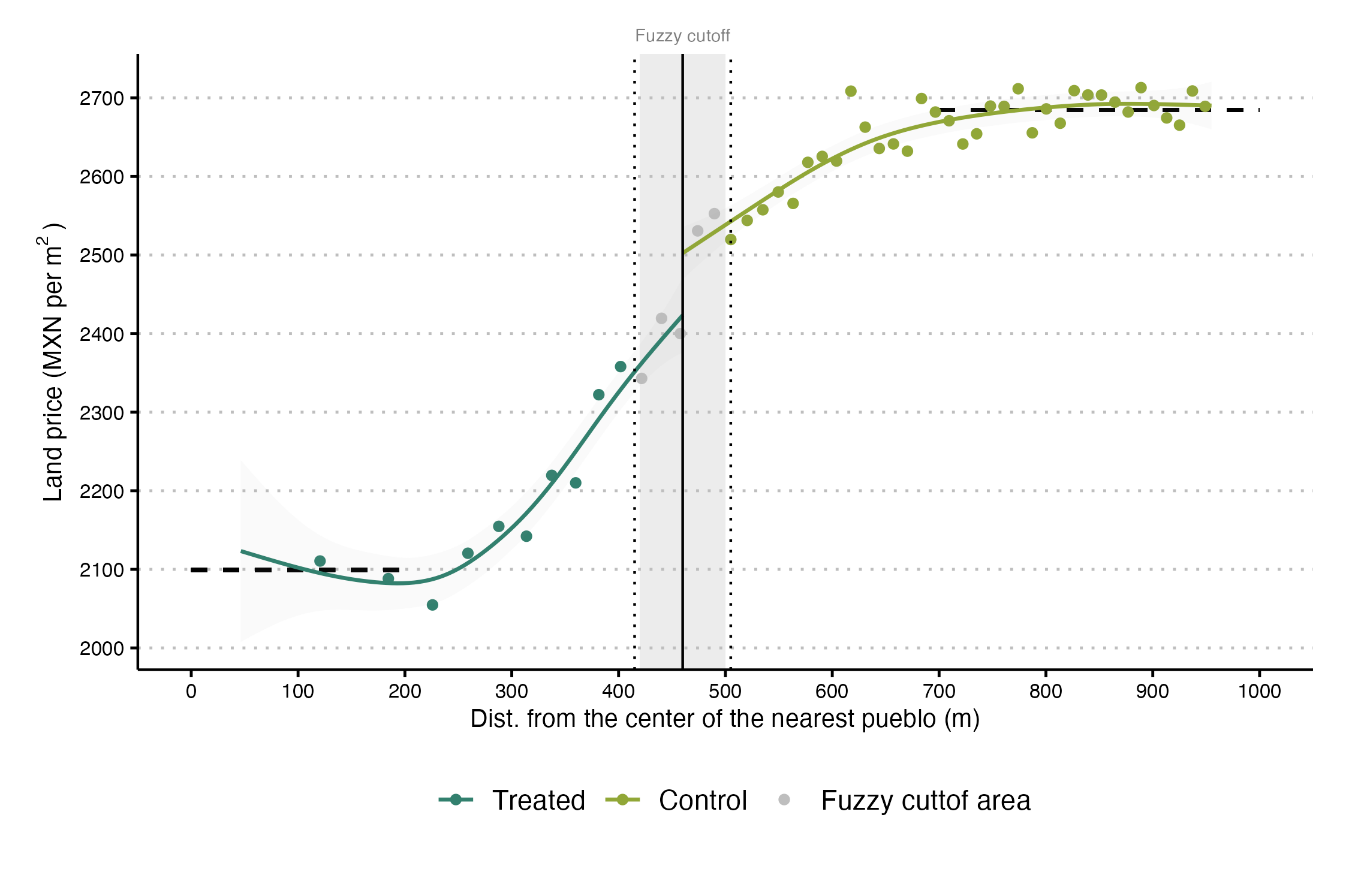

First, we found a “penalty” for proximity to pueblo centres: plots within 0 to 200 metres of a pueblo centre are approximately 25% cheaper than those 700 to 1,000 metres away. Second, there is a significant land value drop at the boundary: properties just within the pueblo boundary are valued 4.9% to 5.3% lower than those just outside (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Land value penalties

Notes: Bin scatter of the price per square metre of urban land parcels (y-axis) vs. the parcels’ distance to the centre of the nearest pueblo measured in metres (x-axis). The grey vertical area is the fuzzy cutoff. The first (second) vertical dotted line marks 420 (500) metres from the nearest pueblo centre. The grey vertical line marks 460 metres from the nearest pueblo centre. The observations to the left of the grey vertical area are treated units, while those to the right are control unit). The dashed horizontal represents the mean price per square metre for plots within 0 to 200 metres from the centre of the nearest pueblo and the mean price for plots with a distance of 700 to 1000 metres from the centre of the nearest pueblo.

Additionally, pueblos with historically majority-Indigenous populations exhibit the most significant penalties. By contrast, pueblos with more diverse populations, typically closer to the colonial city centre, show little or no effect on land values. This suggests that proximity to the colonial centre may have reduced the long-term impact of segregation, likely due to increased competition for land and a more varied set of historical influences.

Why does this colonial segregation policy have persistent effects?

Despite Mexico City’s many transformations over the centuries—from independence and the Porfiriato era to the post-revolutionary period and modern development—the effects of this colonial segregation policy still linger. Why does a historical reality from over 500 years ago continue to influence land values?

We identify three main factors that have perpetuated these inequalities over time:

- Weak property rights protection: Following Mexico’s independence in the 19th century, pueblos de indios lost the legal protections they had under Spanish rule, leading to expropriations and land fragmentation through liberal reforms. These weakened property rights prevented Indigenous residents from accumulating wealth from their land, discouraging investment.

- Unequal provision of public goods: Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, infrastructure and public services were concentrated in wealthier parts of the city, leaving pueblos and other peripheral areas underserved. While the city centre enjoyed investments in transportation, lighting, and public facilities, pueblos received minimal attention. This underfunding reinforced negative expectations and discouraged investment, solidifying pueblos’ status as low-value areas.

- Enduring social stigmas: Negative perceptions of pueblos as poor, low-status neighbourhoods have lingered, creating a cycle of underinvestment. Many residents continued to view these areas as overcrowded and disadvantaged, which reinforced the land value penalty. This stigma, rooted in historical policies, continues to shape perceptions today.

We supplemented these findings by digitising historical maps of public goods and services, such as lighting, tramways, post offices, government buildings, and paved roads. These maps show a clear pattern: public services were systematically scarcer in areas influenced by pueblos de indios, especially in exclusively Indigenous pueblos. Even today, while pueblos have similar access to paved streets, lighting, and other public goods, the quality often lags behind. For example, schools in these areas tend to have higher student-to-teacher ratios, indicating lower educational quality.

The significance of colonial segregation in Mexico City today

The study’s findings underscore how historical policies can have a lasting impact on city structure, even if the original policy is no longer in place. Our study contributes to a growing body of research showing how historical inequalities and spatial segregation policies continue to shape cities worldwide.

Our study also offers insights for modern public policy. For example, several countries currently implement policies that segregate neighborhoods based on income, nationality, or ethnicity. Our findings suggest that even “temporary” segregation policies can have lasting impacts on urban structures and land values, persisting centuries after they are eliminated.

To address these impacts, policies that prioritise public investment and high-quality infrastructure in historically underserved areas could help counteract long-standing inequalities. By improving access to public goods and addressing negative perceptions, urban planners and policymakers could uplift these communities, reducing disparities in land values across the city. However, our findings show that simply providing public goods is not enough; the quality of these goods is crucial. Such policies, focused on quality, could foster greater economic inclusion and reshape city landscapes to be more equitable.

References

Baldomero-Quintana, L, L G Woo-Mora, and E De la Rosa-Ramos (2025), “Infrastructures of race? Colonial indigenous segregation and contemporary land values,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, 110: 104065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2024.104065.