Legibility—systematised information about citizens—and legal enforcement can produce sustained, cost-effective increases in tax collection.

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out Issue 1 of our VoxDevLit on Taxation.

Lower-income countries have low tax capacity because they have little information about their citizens

Many lower-income countries struggle to collect adequate tax revenues because they know very little about their citizens, such as their location, income, assets, and even their identities. In contrast to higher income countries where identifying citizens is, for the most part, a given, many lower-income countries have sparse and inaccurate taxpayer databases (Nyanga 2021), that prevent them from establishing the extent of their tax base. A stark illustration of this is that 45% of Sub-Saharan Africans do not have any official proof of identity by which the government can identify them (World Bank 2022). Without the ability to identify citizens, it is difficult for countries to build effective tax systems. Political scientist James Scott describes the extent of a central state’s knowledge of its citizens as how “legible” society is to the state (Scott 1998). High-income countries have had to achieve this before significantly increasing their tax capacity (Brambor et al. 2020).

Why is information on citizens not enough to increase tax revenue?

In a recent paper (Okunogbe 2025), I examine the conditions under which information on taxpayers may lead to higher tax revenue using a modification of the Allingham and Sandmo (1972) framework for studying tax compliance. If citizens assume they are unknown to the state, they may choose not pay taxes (despite there being strong penalties for not doing so), as they do not expect that these penalties will apply to them. Similarly, if citizens assume they are identifiable by the state, but are unaware of the consequences of tax evasion, they may still not comply. For these reasons, a combination of legibility and enforcement is necessary to meaningfully increase tax compliance and revenue.

A randomised experiment on the impact of legibility and enforcement in Liberia

From 1989 to 2003, Liberia was ravaged by a brutal civil war that decimated the state’s capacity across different sectors, leaving legibility practically non-existent. As of 2015, Liberia only had 23,000 registered taxpayers, despite its population of 4.5 million (LRA 2015).

For this study, I collaborated with the Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA) to investigate the roles of legibility and enforcement on tax payment in Greater Monrovia, where only 5% of properties were registered with the LRA (Olabisi 2013). During the first phase of this investigation, I worked closely with LRA enumerators, collecting information on properties via door-to-door interviews with residents. This information was then used to develop a new electronic database that documents property characteristics, such as location and ownership.

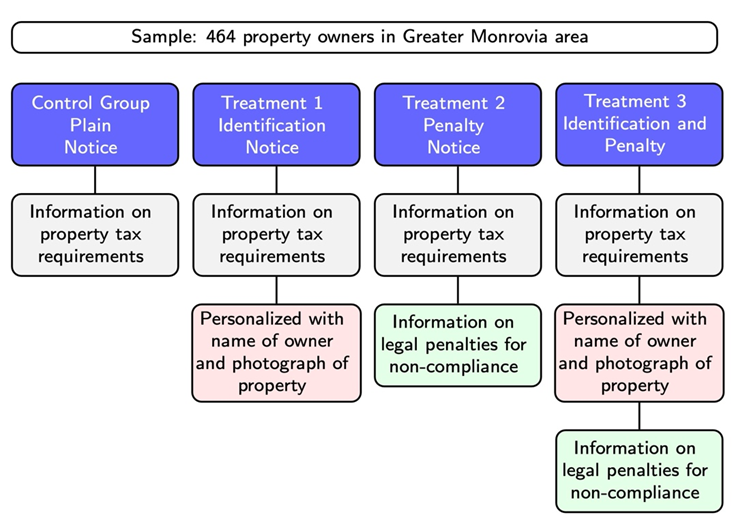

Next, we examined the impact of alerting previously unregistered property owners that the government had acquired information about them from this new database. Specifically, we randomly split our sample into four groups and sent different tax notices to each group. The control group received a generic notice with information about the tax payment procedure and a request for compliance. One treatment group received a notice with this same information, along with property-specific identification information from the new database, specifically, the property owner’s name and a photograph of the property (Treatment 1). Another treatment group received a notice that included this identification information, as well as information on the legal penalties for noncompliance (Treatment 3); the purpose of this was to determine whether the identification information would have more impact if presented alongside legal penalties. A final treatment group received a notice that only featured the penalties for noncompliance (Treatment 2).

Figure 1: Experimental design

The combination of legibility and enforcement lead to greater tax compliance

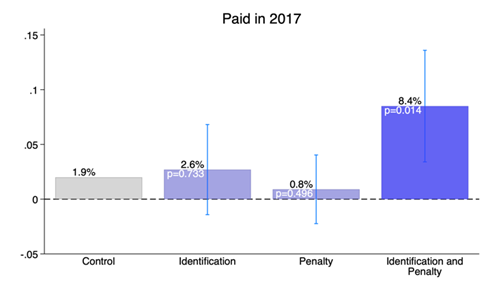

Consistent with the theoretical prediction, the combined identification and penalty notices increased property owners’ compliance, making them over four times more likely to pay property tax. The likelihood of payment increased from 1.9% to 8.4%, which is substantially greater than the increases observed from deterrence nudges in settings where no change in state capacity has occurred (Antinyan and Asatryan 2024). Unlike the combined identification and penalty treatment, the identification-only and penalty-only treatments had no impact on tax payments. Our results also suggest that the identification- and penalty-only notices are complementary, as the combined treatment had a greater impact than the sum of these two individual treatments.

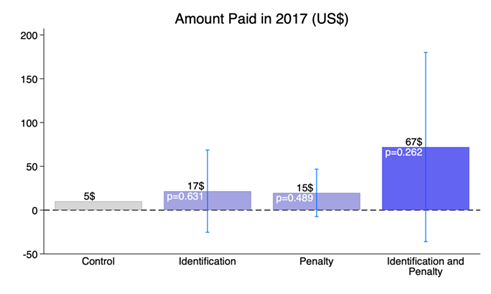

Remarkably, the amount of tax paid by those who received the combined notice increased thirteenfold in the first year. However, this effect size is imprecisely estimated due to the small number of payments. We also find some suggestive evidence that the intervention raised more revenues from owners with higher-valued properties, making it a progressive tax.

Figure 2: Short-term results

A cost-effective intervention with a sustained impact

By the end of the first year of the intervention, the total revenue raised exceeded the cost of conducting the property enumeration, delivering notices, and processing payments. Over the four-year study period, the intervention generated US$5 per $1 invested, a cost-of-collection ratio of 20%. While this is much higher than the average ratio of 4.65% in Liberia (ATAF 2018), it reflects the intervention’s high fixed costs, the burden of which the central government, not the tax administration, typically bears. And, while this study shows that the likelihood of payment becomes smaller over time, the combined treatment group still had a 2.6 percentage point higher likelihood of payment three years after.

Policy lessons from a tax collection capacity intervention

The results from this research have two main policy implications. First, they demonstrate that legibility is essential for tax compliance. Much of current economic research implicitly assumes that governments have information on the existence of the tax base and instead focuses on the importance of information needed to verify the size of the tax base, for example by using third-party information from employers and business partners as in Kleven et al. (2011). The results of this study highlight the fundamental identification gaps in many lower countries and the need for states to make crucial investments in legibility tools such as digitised civil/property registries and taxpayer databases to better understanding their potential tax base.

Second, our findings indicate that making the tax base legible is only the first step. This must be followed by stricter legal enforcement to yield significant increases in revenue. The lack of commensurate increases in enforcement may explain the disappointing revenue impacts of recent large taxpayer registration campaigns as in Benhassine et al. (2018), Gallien et al. (2023), and Mascagni et al. (2022).

Currently, there is significant policy enthusiasm for using technology to improve legibility. As a result, donors and governments may be tempted to overprioritise investments in costly IT projects as opposed to increasing traditional enforcement, as enforcement is politically costly and often requires coordination with other government agencies (Arewa and Davenport 2022). Whether recovering from war or improving long-standing infrastructure, it is essential that states understand the constraints on their tax capacity and invest in legibility and enforcement accordingly.

References

Allingham, M G, and A Sandmo (1972), “Income tax evasion: A theoretical perspective,” Journal of Public Economics, 1: 323–38.

Antinyan, A, and Z Asatryan (2024), “Nudging for tax compliance: A meta-analysis,” The Economic Journal, ueae088.

Arewa, M, and S Davenport (2022), “The tax and technology challenge,” in R Dom, A Custers, S Davenport, and W Prichard (eds.), Innovations in Tax Compliance: Building Trust, Navigating Politics, and Tailoring Reform, Chapter 7, 171–204. Washington, DC: World Bank.

ATAF (2018), “African Tax Outlook 2018,” African Tax Administration Forum.

Benhassine, N, D McKenzie, V Pouliquen, and M Santini (2018), “Does inducing informal firms to formalize make sense? Experimental evidence from Benin,” Journal of Public Economics, 157: 1–14.

Brambor, T, A Goenaga, J Lindvall, and J Teorell (2020), “The lay of the land: Information capacity and the modern state,” Comparative Political Studies, 53(2): 175–213.

Gallien, M, G Occhiali, and V van den Boogaard (2023), “Catch them if you can: The politics and practice of a taxpayer registration exercise,” ICTD Working Paper 160, Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Kleven, H J, M B Knudsen, C T Kreiner, S Pedersen, and E Saez (2011), “Unwilling or unable to cheat? Evidence from a tax audit experiment in Denmark,” Econometrica, 79(3): 651–92.

LRA (Liberia Revenue Authority) (2015), “Annual report for fiscal year 2014/15,” The Liberia Revenue Authority.

Mascagni, G, F Santoro, D Mukama, J Karangwa, and N Hakizimana (2022), “Active ghosts: Nil-filing in Rwanda,” World Development, 152: 105806.

Nyanga, M (2021), “Performance outcome area 1: Integrity of the registered taxpayer base—essentials of a high integrity taxpayer register,” TADAT Insights.

Olabisi, O (2013), “Optimising real estate tax in Liberia: Implications for revenue performance and economic growth,” Working Paper, The International Growth Centre (IGC).

Okunogbe, O (2025), “Becoming legible to the state: The essential but incomplete role of identification capacity in taxation,” CEPR Discussion Paper No. 19916, CEPR Press, Paris & London.

Scott, J C (1998), Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed, Yale University Press.

World Bank (2022), “ID4D Global Dataset—Volume 1 2021: Global ID coverage estimates,” World Bank Group, Washington, DC.