Industrial policy prioritises growth in specific sectors. Yet there is little agreement about how to target sectors in practice, especially in developing countries, and many argue that governments cannot pick winners. So, how have governments’ export promotion agencies been effective in coordinating public inputs to grow industries?

What is politically acceptable in economic policy has shifted. Global leaders now argue industrial subsidies can achieve diverse goals such as national security, pollution abatement, and lower inequality. Although economists discouraged these tools in the past, insights from macroeconomics increasingly make a case for their use. Still, this discussion often centres on the world’s largest economies.

Most of the empirical evidence on contemporary industrial policy comes from China and Europe; meanwhile, the policy changes getting the most global attention are in the US. It is not obvious whether policies designed for these economies will be useful in others, given their differing goals and circumstances. This is concerning as developing countries have little guidance on whether and how to support specific industries.

Targeting industrial policy for economic development is difficult

In some ways, larger economies have an easier problem to solve, given their goals of national security. Although their industrial policies are promoted as serving multiple objectives (EBRD 2024), they are often aimed at securing military advantage. For instance, not only do subsidies on shipbuilding and semiconductor industries serve a civilian purpose, but they also ensure production capacity during war (Barwick et al. 2024, Bown and Wang 2024). In these cases, industry targeting is straightforward.

This problem is made harder when the goal is economic development—measured by productivity, job creation, and/or private investment. In this case, which industries should be targeted? And how much support should individual industries receive when the opportunity cost is a project that benefits multiple industries? This is where the critique 'government can’t pick winners' has bite.

When benchmarks lag, it is easier to motivate investment in fundamentals such as schooling, ease of doing business, or power infrastructure, as opposed to support for a single industry with few, potentially unviable firms. Yet, as countries strengthen their fundamentals, the cost of marginal improvement rises. More so than in the past, the highest-return investments for development are industry-specific, such as targeted infrastructure projects or regulatory reforms. Governments with limited bandwidth must find a way to prioritise these industries, assess their opportunities and constraints, and address key challenges.

Existing approaches to prioritising industries for development

Economists currently take two approaches to prioritising industries for development. I will refer to these as 'picking winners', while setting aside the question of selecting specific firms within an industry—a separate challenge that is not required in many interventions (Schneider 2013).

In the 'technical' approach, a model is specified, externalities are carefully measured, and subsidies are recommended for industries that have greater externalities than others. Evidence from this approach may motivate subsidies in industries with greater external economies of scale, network centrality, complexity, learning-by-doing, and/or gains from coordination (Lashkaripour and Volodymyr 2023, Buera and Trachter 2024, Atkin et al. 2021, Hong 2025, Garg 2025). The 'agnostic' approach assumes more uncertainty than the technical approach, noting the scarcity of evidence on the impact of subsidies and scepticism surrounding the assumptions of certain models. This approach argues that successful industrial policy is less about picking winners, and more about letting losers go, encouraging governments to experiment with identifying effective strategies.

Both approaches have limitations, and conflict with one another. The technical approach often requires using restricted data, making it less accessible to non-technical audiences. The agnostic approach encourages intervention but provides little guidance on implementation.

In a recent evidence review, I review a third approach, a compromise, perhaps, which best reflects the approach countries actually use in their development plans: targeting the export sector, and within it, industries that either have already achieved scale (measured by 'revealed comparative advantage') or have growth potential (measured by 'technological relatedness'), and which have international demand growth and limited competition (Reed 2024). Crucially, the prioritisation here is not about targeting industries to receive subsidies, as in the technical approach. Instead, it is an earlier, strategic step in which governments identify sectors, acquiring information on constraints and market/government failures, before deciding whether intervention is needed. Industries are thus prioritised by their scale or potential to achieve scale in a specific context, a necessary condition to realise returns from supporting that sector.

Exports as a path to development

Why focus on exports at all? Historically, export-led industrialisation has been a reliable path to development. However, automation, competition from economies of scale in China, and increasing trade restrictions in rich countries call this path into question (Goldberg and Ruta 2025). Even an alternative export-led strategy focused on tradable services, such as business process outsourcing or nursing, faces risk from artificial intelligence and immigration restrictions (Gill and Mattoo 2024).

In this context, Rodrik and Stiglitz (2024) argue for a new development strategy that does not rely on exports. They instead emphasise two pillars: (1) investment in green infrastructure, and (2) policy to raise productivity in labour-intensive non-tradable services, such as healthcare, retail, and transportation. Yet, there is reason to be sceptical over how much each of these can deliver. Although new power plants rely on solar and wind, instead of coal and gas, there is little reason to expect these investments to accelerate growth without increased foreign aid or lowered interest rates.

Moreover, increased investment in climate adaptation leaves less funding for productive infrastructure. As for productivity in services, randomised control trials raise questions over the ability of capacity-building interventions to boost productivity, such as those involving microfinance, shortening supply chains, and training entrepreneurs (IPA 2015, Iacovone and McKenzie 2019, Anderson and McKenzie 2022). Even when these interventions are effective, their impacts are often not transformative. It is hard to imagine how firm-based interventions, even deployed at scale, would deliver the same growth as a boost to aggregate demand from exports.

Goldberg and Reed (2023) highlight the role for exports in a world with reduced opportunities for export-led industrialisation. In their framework, development occurs after two steps: (1) there is an initial income boost from traditional exports (e.g. food, energy, minerals; more recently, low-wage manufacturing), and (2) that income is reinvested in non-traditional industries that raise wages, leading to development. Firm-level increasing returns to scale are the assumption behind the second step: development will not occur without sufficient demand for non-traditional industries.

Historically, this scale was achieved through the international market, with export-led industrialisation. In the modern era, this can be achieved through the domestic middle class, which is significant in many countries. Middle class demand raises productivity in the non-tradeable sector without requiring industrial policy for services, as in Rodrik and Stiglitz (2024). Rather, this demand is driven by income from traditional exports that translates into additional demand for all sectors, including non-tradable services.

Societies develop faster when traditional export income is distributed equitably. Natural resource dependent economies have developed to varying degrees along these lines. For instance, Saudi Arabia remains largely oil-dependent but has achieved productivity growth in the domestic service sector fuelled by demand from a middle class created, in part, by government employment, universal healthcare, and free college education. Though most countries lack Saudi Arabia’s commodity margins, their traditional export has grown income, such as for apparel workers in Bangladesh and cocoa farmers in Ghana, which feeds domestic demand. Overall, this framework suggests that traditional exports are still necessary to drive development. Productivity growth in the domestic service sector can be a channel for development but remains an unlikely root cause.

Balancing current comparative advantage with potential future comparative advantage in industrial policymaking

Historically, industrial policy has focused on non-exporting industries as opposed to industries already exporting at scale, or latent rather than revealed comparative advantage. For example, South Korea discovered a latent comparative advantage in heavy and chemical industry, moving away from its revealed comparative advantage in rice (Lane 2024). One risk of this new era of industrial policy is that there are fewer latent comparative advantages than before. This suggests that it is beneficial to double down on current comparative advantages and redistribute those gains to strengthen the middle class.

Interestingly, this is what countries appear to be doing, as the use of industrial policy is more common in industries with revealed comparative advantage (Juhász et al. 2023). Within these industries, countries may prioritise further by targeting industries with expected international market growth and low competition from other exporters. This is especially true of countries focusing on critical minerals. Of course, there are risks to this strategy. Indonesia has used industrial policy to develop its metals sector only to find its domestic middle class shrinking (Lakshmi and Mariska 2025). But it is difficult to disentangle whether this is due to picking the wrong sectors, or picking the wrong policies. The shrinking of the middle class may be due to other industrial policies, such as local content requirements, incentivising low-wage assembly in the domestic market, and hindering latent comparative advantage in export manufacturing that has been captured by neighbouring Vietnam (Reed et al. 2024).

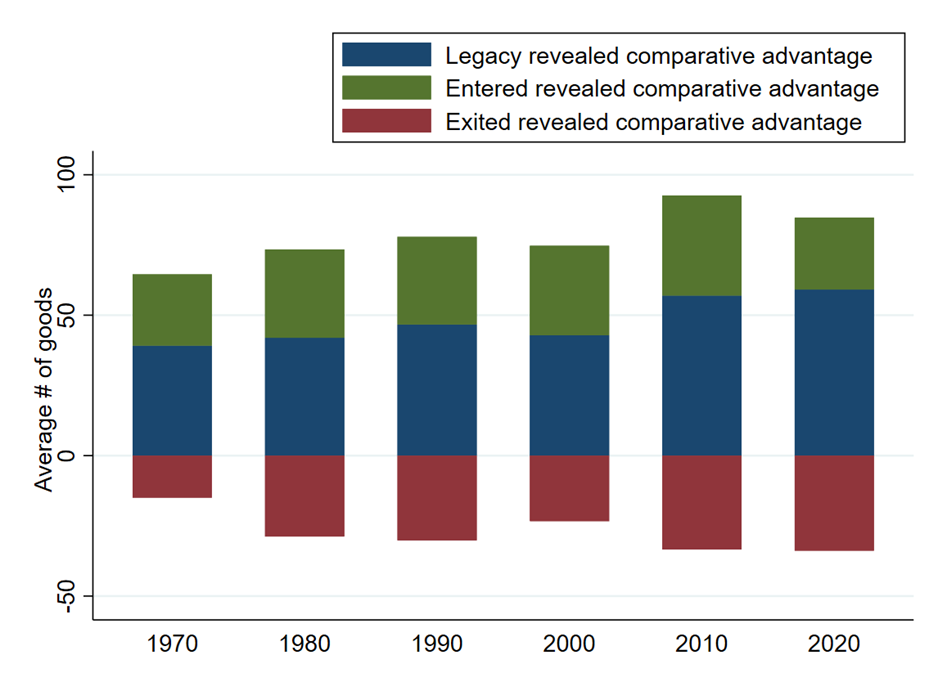

To provide a sense of how governments can strike a balance between targeting revealed and latent comparative advantage, Figure 1 reports the count of goods within three categories for the average developing country: (1) legacy revealed comparative advantage, or goods that had an advantage that year as well as ten years ago; (2) entered revealed comparative advantage, goods that had an advantage that year but not ten years ago; and (3) exited revealed comparative advantage, goods that do not have an advantage but did so ten years ago.

Figure 1: Dynamics of comparative advantage in developing countries

Note: Sample includes all countries with less than $10,000 in GDP per capita measured in 2017 dollars at purchasing power parity in a year. Goods are defined by the four-digit SITC, so there are about 1,000 possible goods in each year (service exports are excluded, as the series are not available in early decades). Source: Figure 2 in Reed (2024).

In any decade, roughly half of revealed comparative advantages are legacy, and the other half are recent entrants. This suggests that, to match the distribution of industries in the economy, governments will want to prioritise roughly half revealed and half latent comparative advantage. This recommendation contrasts with both the historical approach of targeting mainly latent advantage, and the approach observed in the data, in which countries mainly target revealed comparative advantage. Both sectors can have market and government failures that need to be studied and addressed.

A benefit of targeting industries with already high productivity, as signalled by revealed comparative advantage, is that it can avoid the capture of policy by less productive firms. Despite this benefit, one may argue that industrial policy targeted towards revealed comparative advantage can reduce dynamism, as government support for one sector may divert entrepreneurs away from emerging opportunities. This argument is less persuasive given that comparative advantage is slow-moving. To reduce dynamism, a supported programme would have to persist for longer than four or five years, the typical length of an executive’s term in a democracy.

Targeting can be more valuable for developing countries

Targeting can be more valuable in developing countries as they have fewer revealed comparative advantages. For example, when a country exports fewer commodities, it essential to establish effective public goods and regulations for those sectors. This suggests that, if anything, governments and development agencies should place more emphasis on the sector-targeted approach in developing countries.

This remains true when targeting latent comparative advantage. Hausmann and Klinger (2006) famously developed a measure of product space that predicts which new products countries are likely to transition into, based on technological relatedness to existing revealed comparative advantages (Bahar et al. 2019). As economies shift comparative advantage over time, higher-income countries have a better chance of producing any given product, given their denser preexisting product space and production knowledge. Larger developing economies, such as India and Indonesia, also have a diverse production capacity. The product space is most useful when it is least dense, as it helps countries differentiate medium-risk target industries, where they have a higher degree of technological relatedness, from high-risk target industries, where they lack such relatedness.

These patterns explain the popularity of development strategies that prioritise certain sectors based on technological relatedness, especially in lower-income economies.

Developing countries are unable to be protectionist

Once low- and middle-income countries have prioritised industries, how should they develop them? To reiterate, a government’s first action should not be to protect or subsidise, but to analyse which market or government failures occur and how to address them. This is the WTF ('what’s the failure?') approach.

However, developing countries are especially constrained when it comes to addressing market failures with industrial policy. An export-led development strategy requires market access, and market access requires good relations with trading partners and continued engagement in trade agreements that discipline the use of tariffs and subsidies. While some high-income economies have used these protectionist measures to support industries, developing countries do not have the same privilege. In fact, as of 2023, high-income countries were more likely to pursue policies that "discriminate against foreign commercial interests" (Evenett et al. 2024). Developing countries, on the other hand, lack the fiscal capacity for direct subsidies. They are also more frequently punished by high-income countries using anti-dumping measures (Nunn 2019).

In my essay, I review strategies developing countries can use to promote exports economically and in line with their commitments under trade agreements. These include negotiating market access with key partners; connecting firms with new customers and suppliers; quality certification and standards; sector-specific physical and regulatory infrastructure; and sector-specific public-private dialogue (Reed 2025). While perhaps not as intellectually radical as protectionist measures, there is growing evidence that these interventions can be productive. Export promotion agencies can also serve as institutional hubs to coordinate these interventions.

Export-led targeting lowers the chances of picking losers

Export-led industrialisation seems less likely today than in the past. While demand from a new generation of middle-class consumers can support growth through services, these consumers and their governments still need to generate income from somewhere. Currently, many countries prioritise and support traditional exports, redistributing that income with varying effectiveness. In advanced economies, leaders are becoming increasingly comfortable with prioritising the growth of certain industries. Developing countries should pay close attention to this and not target the same industries or adopt identical strategies to wealthy countries.

Instead of pursuing industry-agnostic policies, countries should prioritise projects that support specific tradable industries, while avoiding those in sectors with unlikely growth. These decisions can be guided by measures such as international market growth, international competition, comparative advantage, and technological relatedness. Unlike protectionism, export promotion provides an alternative to 'industrial policy' that is cheaper, less susceptible to capture by unproductive firms, and permissible under the rules of international trade agreements. Is this a sure way to pick winners? My tentative answer is yes, sort of. Or, at the very least, export-led industrial policy reduces a country’s chances of picking losers, as demonstrated by successful interventions in the past.

References

Anderson, S J, and D McKenzie (2022), “Improving business practices and the boundary of the entrepreneur: A randomized experiment comparing training, consulting, insourcing, and outsourcing,” Journal of Political Economy, 130(1): 157–209.

Anantha Lakshmi, and D Mariska (2025), “Indonesia's shrinking middle class rattles businesses betting on a boom,” The Financial Times.

Atkin, D, A Costinot, and M Fukui (2021), “Globalization and the ladder of development: Pushed to the top or held at the bottom?” NBER Working Paper 29500.

Bahar, D, S Rosenow, E Stein, and R Wagner (2019), “Export take-offs and acceleration: Unpacking cross-sector linkages in the evolution of comparative advantage,” World Development, 117: 48–60.

Barwick, P J, M Kalouptsidi, and N B Zahur (2024), “Industrial policy: Lessons from shipbuilding,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(4): 55–80.

Bown, C P, and D Wang (2024), “Semiconductors and modern industrial policy,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(4): 81–110.

Buera, F J, and N Trachter (2024), “Sectoral development multipliers,” NBER Working Paper 32230.

EBRD (2024), Transition report 2024-25: Navigating industrial policy.

Evenett, S, A Jakubik, F Martín, and M Ruta (2024), “The return of industrial policy in data,” The World Economy, 47(7): 2762–2788.

Garg, T (2025), “Can industrial policy overcome coordination failures? Theory and evidence,” Unpublished manuscript.

Gill, I, and A Mattoo (2024), “Services are the new road to development,” Project Syndicate.

Goldberg, P K, and T Reed (2023), “Presidential address: Demand-side constraints in development—The role of market size, trade, and (in)equality,” Econometrica, 91(6): 1915–1950.

Goldberg, P K, and M Ruta (2025), “The trade shifts redefining economic development,” Project Syndicate.

Hausmann, R, and B Klinger (2006), “The evolution of comparative advantage: The impact of the structure of the product space,” Center for International Development and Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

Iacovone, L, and D J McKenzie (2019), “Shortening supply chains: Experimental evidence from fruit and vegetable vendors in Bogotá,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8977.

IPA (2015), “Microcredit doesn't live up to promise of transforming lives of the poor, 6 studies show,” Innovations for Poverty Action.

Juhász, R, N Lane, and D Rodrik (2023), “The new economics of industrial policy,” Annual Review of Economics, 16.

Juhász, R, N Lane, E Oehlsen, and V C Pérez (2022), “The who, what, when, and how of industrial policy: A text-based approach,” Unpublished manuscript.

Lane, N (2024), “Manufacturing revolutions: Industrial policy and industrialization in South Korea,” SocArXiv, College Park, MD.

Lashkaripour, A, and V Lugovskyy (2023), “Profits, scale economies, and the gains from trade and industrial policy,” American Economic Review, 113(10): 2759–2808.

Nunn, N (2019), “Rethinking economic development,” Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique, 52(4): 1349–1373.

Reed, T (2024), “Export-led industrial policy for developing countries: Is there a way to pick winners?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(4): 3–26.

Reed, T, A S Gonzalez, and M Pasha (2024), “Leveraging foreign direct investment in Indonesia: Assessing foreign investors’ use of domestic suppliers,” World Bank.

Reed, T (2025), “Is there a way to do industrial policy without strong institutions?” World Bank Blogs.

Rodrik, D, and J E Stiglitz (2024), “A new growth strategy for developing nations,” Unpublished manuscript.

Schneider, B R (2013), “Institutions for effective business-government collaboration: Micro mechanisms and macro politics in Latin America,” IDB Working Paper No. IDB-WP-418.

Sungwan, H (2025), “Green industrial policies and energy transition in the globalized economy,” Unpublished manuscript.