Contrary to the Pollution Haven hypothesis, air quality did not deteriorate in Vietnamese cities where urban economic growth has been most rapid. How did Vietnam decouple growth from environmental degradation? And what lessons are there for other developing countries looking to promote economic growth and reduce emissions?

Does international trade improve or degrade environmental quality in developing nations? In an undergraduate sustainability class, students are taught the Pollution Haven hypothesis that trade degrades the developing nation’s air and water quality as polluting activity is offshored from richer nations to the developing country. This hypothesis merits continuous testing because if it is correct then this means that as developing nations grow richer, they grow more polluted. In this case, per-capita GDP growth would over-state increases in well-being.

Environmental economists have introduced a framework for exploring the causal effects of trade and economic development on a geographic area’s environmental quality (Copeland and Taylor 2004, Dasgupta et. al. 2002). The three key components are scale, composition and technique. Scale refers to the total size of the population or the economy. Composition refers to which sectors are large in the economy. For example, if steel production is polluting and if a city’s industrial production is concentrated in steel production, then the city will be more polluted. Technique refers to the emissions of different vintages and types of capital used in the local economy. For example, newer vehicles with better emissions control technology may produce lower emissions per mile of driving.

Measuring the impact of trade on Vietnam’s environment

In our recent research paper, we use this accounting framework to explain Vietnam’s recent economic and environmental performance during a time when its trade with China and the United States has sharply increased (Kahn et al. 2024). We focus on a distinctive policy experiment. In March 2018, the Trump Administration introduced Section 301 China Tariffs and implemented them in phases on all products imported from China. The additional ad valorem duty on top of the normal rate was 25% on 6,874 goods and 10% on 3,771 items.

Moving production to Vietnam allows Chinese firms to jump the tariff wall. Vietnam, a lower-middle-income country neighbouring China, has gained more than any other nation from the trade war. Its physical proximity to China reduces transportation costs. Its cheaper labour and land also make it an ideal choice for this supply chain relocation. Vietnam’s economy has been surging after the initiation of the US-China trade war. Contrary to the predictions made by the pollution haven hypothesis, we document environmental progress in this developing nation.

Four facts about urban growth and the environment in Vietnam after the trade war

Our empirical work documents four major facts.

1. There is a border effect for Vietnam.

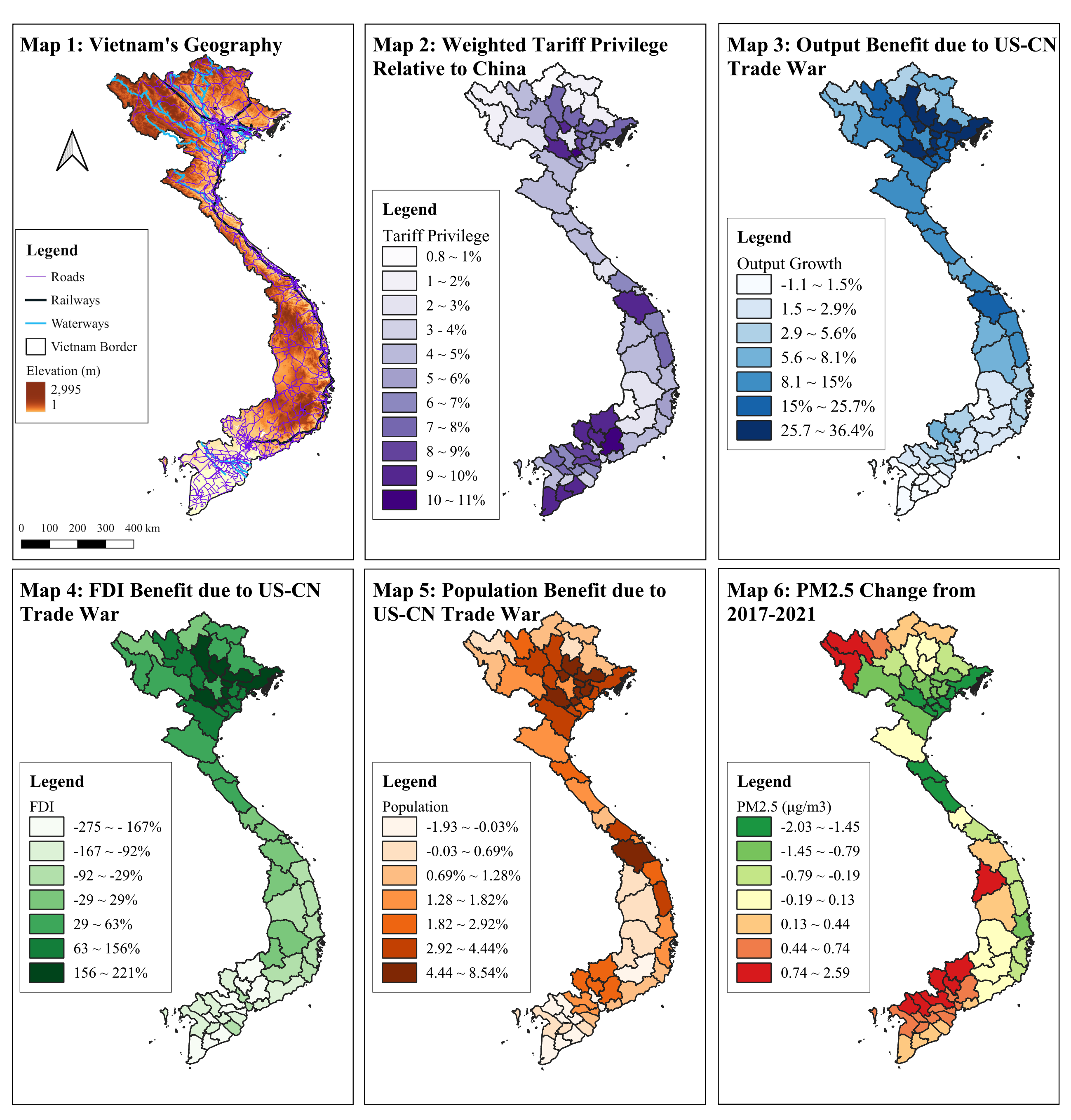

The China Tariffs benefit Vietnam as China’s supply chains can avoid these tariffs by outsourcing adequate production and assembly to Vietnam. Two factors underpin location choice. First, freight costs increase in distance from China, and roadways are cost-effective, as Vietnam’s territory is long and thin (Figure 1, Map 1). Second, Vietnamese cities whose industrial structure complements China’s supply chains gain more.

Figure 1: Vietnam's urban economic growth is associated with air quality improvement

Our analysis portrays the trade-war-induced benefits to production output (Map 3), new FDI capital (Map 4), and population (Map 5). The border effect stands out: Vietnamese locales that benefit most are those closer to China and with a complementary industrial composition that can help manufacturers relocate supply chains to mitigate the trade shock. Southern locales benefit less.

2. Vietnam’s recent economic growth does not sacrifice blue skies

The PM2.5 concentration also notably improves in North Vietnam in Bac Giang, Bac Ninh, Ha Nam, Hoa Binh, Hung Yen, Quang Ninh, and Vinh Phuc, where urban economic growth is most rapid (Map 6). This is direct evidence against the Pollution Haven Hypothesis prediction about the consequences of trade.

3. Renewable energy development matters

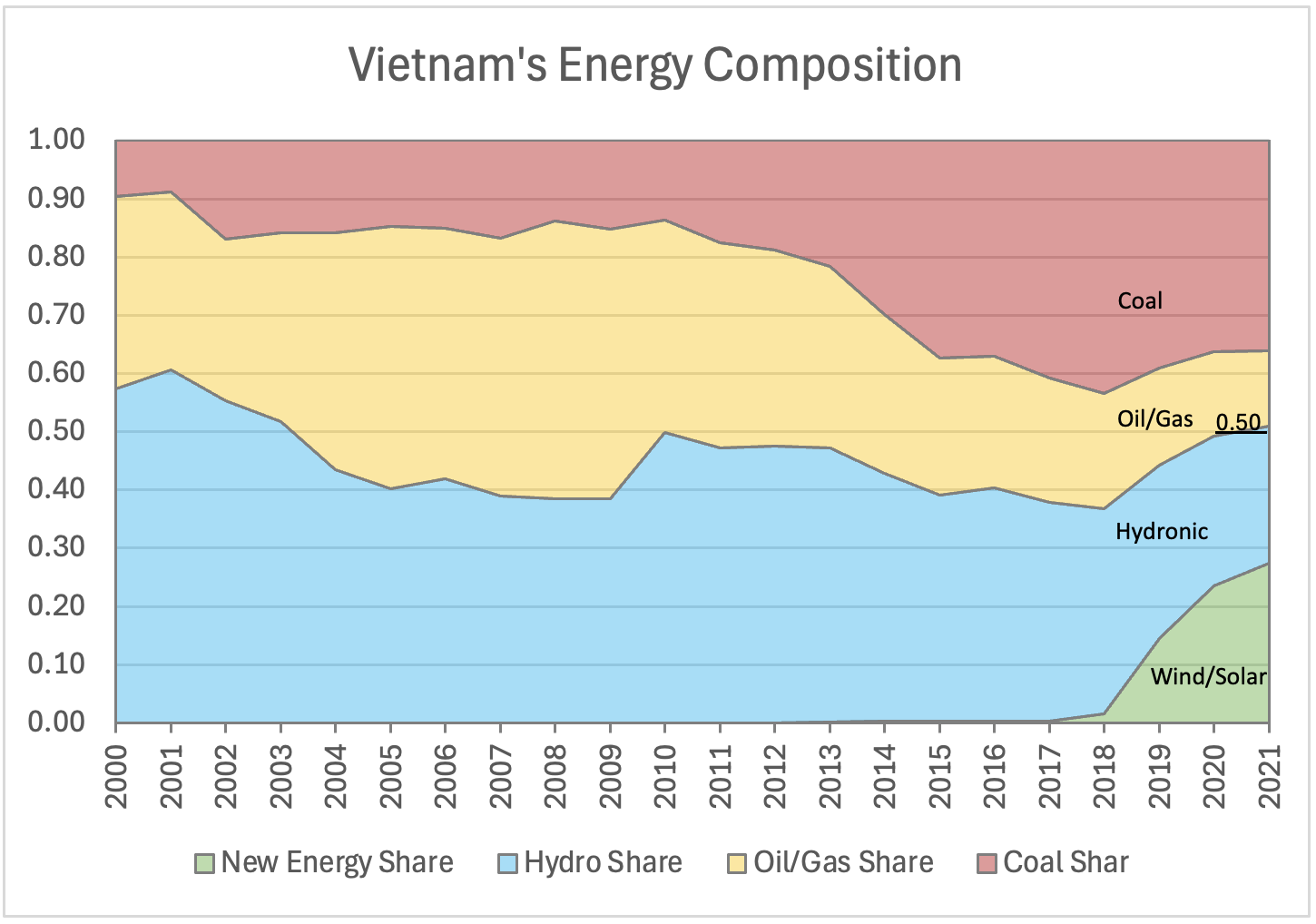

Figure 2 reports Vietnam’s electric power composition across sources over time. Besides ample hydronic power endowment, wind and solar power generation grew sharply after 2018. The electricity share from wind or solar increased by nearly 30% in four years, pushing clean energy’s share to over 50%. Green power growth during a time of surging electricity demand is an impressive achievement.

Figure 2: Vietnam’s energy composition

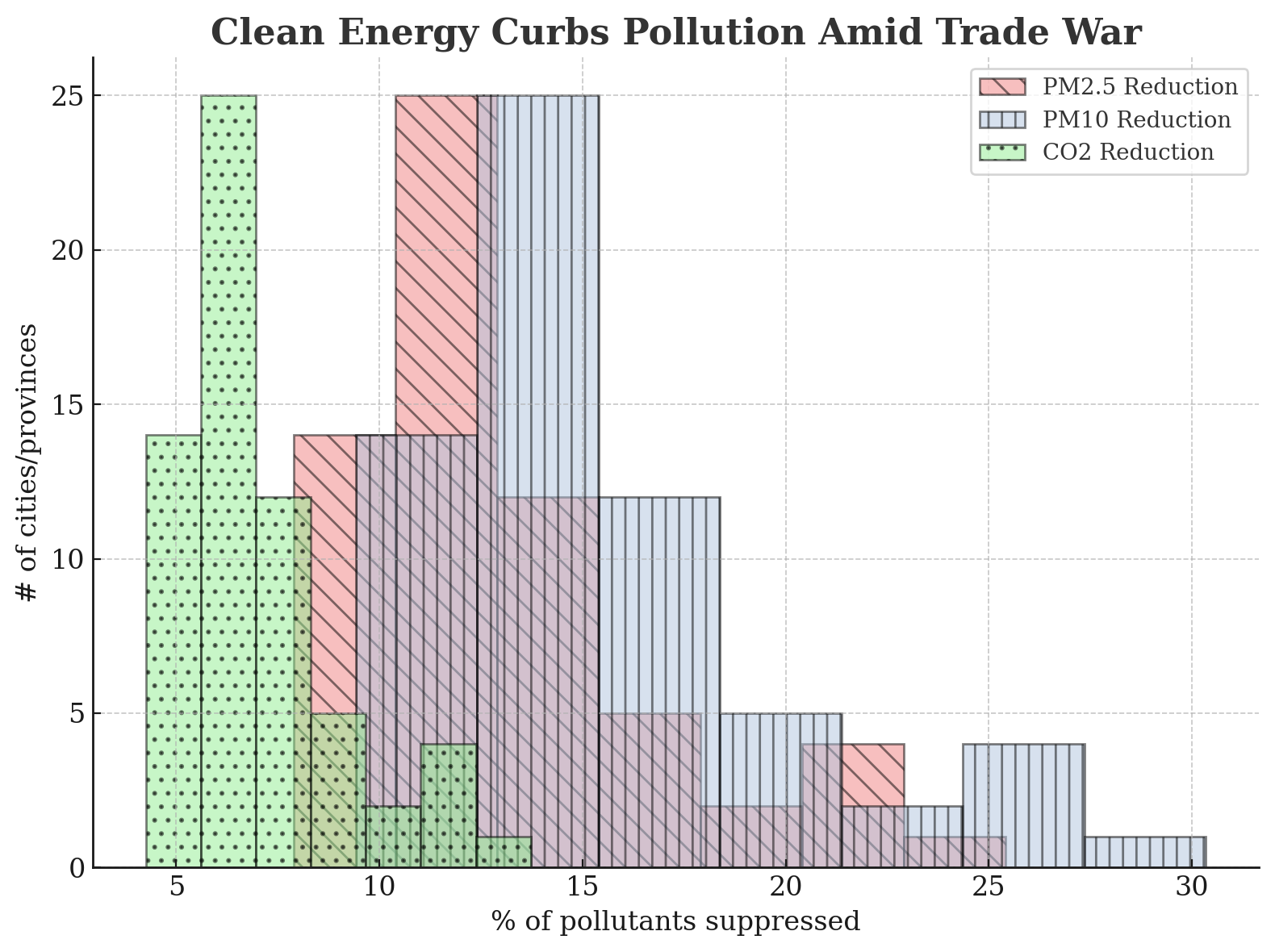

4. Clean energy mitigates pollution from production

Clean energy development introduces both composition and technique effects that together can offset the pollution impact of scale effects. For Vietnam, the scale effects of 1% extra outputs are the sizes of 0.25% more PM2.5, 0.18% more PM10, and 0.01% more CO2. However, these effects will be 1.84%, 2.67%, and 0.81% smaller in size for PM2.5, PM10, and CO2, respectively, if the clean energy share becomes one percentage point higher for the power plants in areas of proximity within 400km. Figure 3 illustrates the percentages of PM2.5, PM10, and CO2 pollutants (which otherwise would have been caused by the output gained from the trade war) that are reduced because of the installed clean-energy power; Vietnam’s clean energy development has notably protected many cities and provinces’ blue skies.

Figure 3: Clean energy mitigates pollution from production

Vietnam’s energy policy during a time of growth

Vietnam plans energy policy decisions decennially. The 7th Power Development Plan (PDP7), approved in 2011, was traditional, targeting 47% and 20% of power from domestic/imported coal and gas by 2020 and minimal shares from wind and solar. Air quality worsened subsequently, especially in North Vietnam. A change happened in 2016, making the PDP7 revision to prioritise renewable power for national energy security and reduce power production’s environmental impact.

Incentivising mechanisms for developing solar and wind power were added between 2017 and 2018. By law, solar and wind projects can raise both foreign and domestic capital. Import duties are waived for imported fixed assets. Ministries and local governments must cooperate efficiently in arranging land, compensation, ground clearance, infrastructure, and human resources to make those renewable energy projects happen in a timely fashion. All electricity is purchased at the stipulated Feed-in Tariffs for 20 years.

Vietnam leverages the natural advantage of wind and solar and supports it with an open, decisive and transparent policy to attract investments to the renewable energy sector. Foreign investments are not merely from neighbouring countries, such as China. Tan (2024) reported an investment influx from advanced economies like Germany, Japan, Korea, and the UAE, bringing frontier technologies. The foreign physical and human capital carrying green production know-how will facilitate pollution progress during a time of urban economic growth (Zheng et al. 2010). At the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), Vietnam pledged itself to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

Lessons for developing countries about how to achieve economic growth and reduce emissions

Vietnam's recent economic growth and pollution progress suggest that eco-economic decoupling, which breaks the positive relationship between growth and pollution, is feasible for developing countries. Many other nations in Asia are endowed with renewable power potential. These nations require financial and human capital to set up the infrastructure for renewable power to thrive. It is well understood that the intermittency of renewable power, such as wind and solar, creates challenges in providing reliable power access. Openness to trade increases the likelihood that developing nations are exposed to the best ideas for pursuing decarbonisation cost-effectively. In this sense, free trade is good for simultaneously reducing PM2.5 concentrations and greenhouse gas emissions in the developing world.

References

Copeland B R, and M S Taylor (2004), "Trade, growth, and the environment," Journal of Economic Literature 42(1): 7–71.

Dasgupta S, B Laplante, H Want, and D Wheeler (2002), "Confronting the Environmental Kuznets Curve," Journal of Economic Perspectives 16(1): 147–168.

Kahn M E, W Liao, and S Zheng (2024), "How the US-China trade war accelerated urban economic growth and environmental progress in Northern Vietnam," NBER Working Paper No. 33126.

Tan R (2024), "Vietnam’s 2025 energy demand spike fuels renewable investment boom," Electric Power, Energy Transition, Renewables, S&P Global, November.

Zheng S, and M E Kahn (2017), "A new era of pollution progress in urban China?" Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(1): 71–92.