Flexible financing for ‘last-mile’ distributors boosted profits across a food supply chain in Kenya.

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out Issue 3 of our VoxDevLit on Microfinance.

Supply chains can be surprisingly complex. In many low- and middle-income settings, large companies often rely on networks of small, independent distributors who travel by foot to sell consumer goods to otherwise hard-to-reach customers (Kruijff et al. 2024). These ‘micro-distributors’ operate at the far edge of the supply chain, with no formal employment contracts, thin profit margins, and high levels of economic risk.

In a field experiment in Kenya, we partnered with one of the world’s largest food manufacturers (pseudonymously “FoodCo”) to evaluate whether investment-appropriate financing contracts could help their independent distributors improve their business performance. We found that tailoring repayment terms to better share risk and rewards—compared to a standard, rigid debt contract—significantly boosted distributors’ profits. Crucially, these more flexible contracts took advantage of detailed administrative data on monthly performance. These findings underscore the promise of improved observability enabled by digitisation: with richer data, financial contracts can be designed to incorporate greater risk-sharing (Fischer 2013, Meki 2024), potentially opening new opportunities for mutually beneficial investments.

The challenge: Why good investments don’t happen on their own

Most micro-distributors in low- and middle-income settings are often severely credit-constrained, making it difficult for them to save enough for ‘lumpy’ investments such as transportation assets that could extend their geographic reach and earnings. Traditional microcredit has shown limited average impacts on business growth (Banerjee et al. 2015, Meager 2019), partly due to its rigid repayment schedules, which often fail to accommodate fluctuating incomes (Barboni and Agarwal 2023, Battaglia et al. 2024, Field et al. 2013). In our setting, FoodCo had never directly financed its distributors, viewing such lending as overly complex, risky, and outside the company’s core operations.

To address these barriers, we partnered with a local lender and provided access to FoodCo’s administrative data for distributors seeking a bicycle. We tested four distinct financing contracts:

- Standard Debt: Fixed monthly repayments for one year, with a 15% mark-up.

- RevShare: A lower fixed repayment plus a percentage of monthly profits—less is owed during low-profit months, more in high-profit months.

- IndexShare: Similar to RevShare, but the variable portion depends on average local profits in a distributor’s region, reducing the burden of common shocks without taxing individual effort directly.

- Hybrid: Starts like RevShare but ends once total payments reach those due under the debt contract. This contract gives distributors both repayment flexibility in tough months and a strong incentive to work harder to pay off the loan quickly.

We worked with 161 micro-distributors, randomly assigning each to a control group or one of the four contract offers. Our randomised design, combined with daily purchase records, yielded a dataset of just under 3,000 distributor-month observations for our main empirical analysis.

What the data shows: Large, lasting improvements from better finance

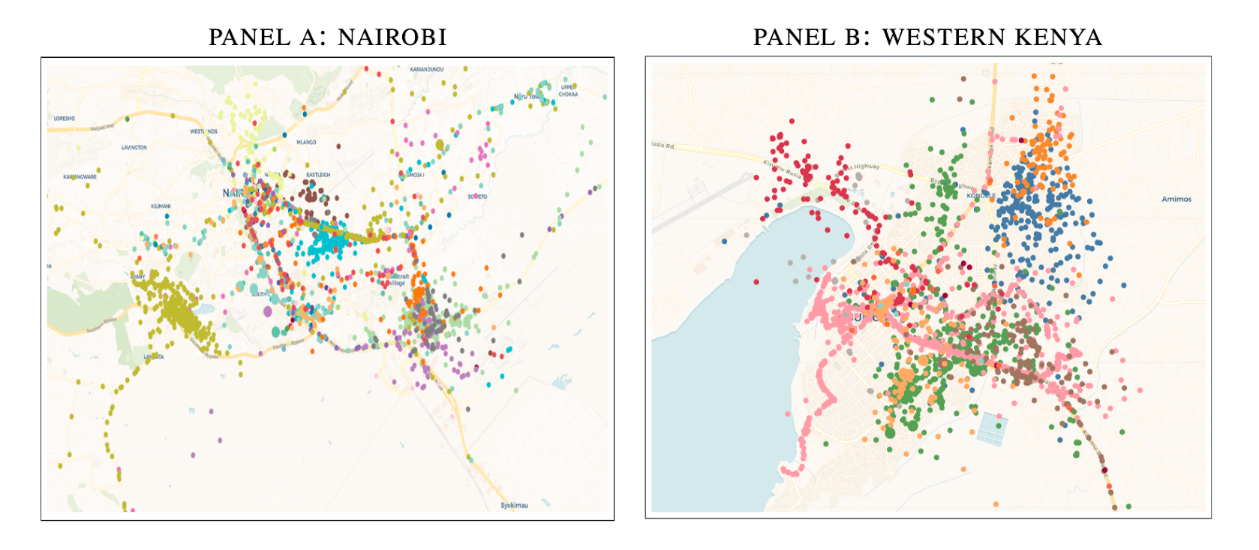

Overall take-up was approximately 60%. Acceptance rates reached roughly 70% for the Hybrid and Debt contracts, compared to about 50% for RevShare and IndexShare. Distributors who were offered any financing contract substantially outperformed those in the control group: on average, they nearly doubled their monthly profits from selling FoodCo’s products. They also improved their business practices and travelled farther, visiting stockpoints more often, and serving additional markets. We find no evidence that these gains displaced their other income sources or took business away from their peers. Instead, GPS data and surveys suggest that micro-distributors used bicycles to tap into previously unreachable markets and customers.

Notes: Panels A and B display GPS data for distributors. Each colour depicts the travel patterns of a distinct individual across Nairobi and Western Kenya—the two largest regions in our sample. On average, distributors traveled 4.8 km per day. We removed outliers (the top 10% of extreme distances) to focus on typical travel patterns and market activity.

Among the four contracts, the Hybrid contract delivered the largest impact—significantly more than the Debt contract. These gains appeared quickly and remained substantial over three years. This pattern aligns with classic theories of risk-sharing (Stiglitz 1974, Udry 1994): when financing contracts provide insurance against negative shocks but still preserve incentives for effort, they can outperform standard debt contracts. To rationalise these findings, in the paper we develop a simple theoretical model of a risk-averse distributor weighing the trade-offs between implicit insurance and effort, and we show how the hybrid contract effectively balances both by offering repayment flexibility while preserving strong incentives to clear the debt sooner.

Why improved financial contracts matter for business, workers, and policymakers

The benefits extended beyond the distributors. Stockpoints that sold the product to these distributors, and FoodCo itself, also earned more. Across the entire supply chain, the value created was very large relative to the bicycle’s cost, with substantial mutual gains and notably high cost-benefit ratios for all contracts—especially the Hybrid contract. Under a highly conservative assumption that the treatment effects cease immediately after the project, we still estimate a cost-benefit ratio of 10.8.

For policymakers, this highlights a clear opportunity: where performance data is available, flexible and performance-contingent financing can unlock productive investments. This is particularly relevant as large firms increasingly rely on gig-like arrangements with small-scale distributors, who often face high income volatility and limited access to credit. By harnessing improved data and digital financial tools to tailor contracts more appropriately, firms can boost incomes for some of the poorest entrepreneurs while also enhancing their own bottom line.

The road ahead: Removing hurdles and scaling up

Why don’t more large companies already do this? Regulatory and practical barriers may discourage them. Providing credit requires licenses, compliance with financial regulations, and the complexity of loan enforcement. Our study shows that partnering with an established financial institution—and leveraging the large supplier’s performance data—can yield mutually beneficial outcomes.

As digital technologies continue to spread and data become more readily available, other sectors—such as agricultural supply chains, ride-sharing, and online platforms—could adopt similar strategies. Whenever performance metrics are observable and profitable investments can be identified, flexible financing that aligns incentives holds the promise of boosting returns for both small entrepreneurs and the larger companies that supply them.

References

Banerjee A, D Karlan, and J Zinman (2015), "Six randomized evaluations of microcredit: Introduction and further steps," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7(1): 1–21.

Barboni G, and P Agarwal (2023), "How do flexible microfinance contracts improve repayment rates and business outcomes? Experimental evidence from India," Working paper.

Battaglia M, S Gulesci, and A Madestam (2024), "Repayment flexibility and risk taking: Experimental evidence from credit contracts," The Review of Economic Studies 91(5): 2635–2675.

Casaburi L, and J Willis (2024), "Value chain microfinance," Oxford Review of Economic Policy 40(1).

Field E, R Pande, J Papp, and N Rigol (2013), "Does the classic microfinance model discourage entrepreneurship among the poor? Experimental evidence from India," American Economic Review 103(6): 2196–2226.

Fischer G (2013), "Contract structure, risk-sharing, and investment choice," Econometrica 81(3): 883–939.

Jack W, M Kremer, J de Laat, and T Suri (2023), "Credit access, selection, and incentives in a market for asset-collateralized loans: Evidence from Kenya," The Review of Economic Studies 90(6): 3153–3185.

Kruijff D, S Sawhney, and R L Wright (2024), "Empowering small giants: Inclusive embedded finance for micro-retailers," Focus Note 2024, Washington, D.C.: CGAP. Retrieved from https://www.cgap.org/research/publication/empowering-small-giants-inclusive-embedded-finance-for-micro-retailers.

Meager R (2019), "Understanding the average impact of microcredit expansions: A Bayesian hierarchical analysis of seven randomized experiments," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11(1): 57–91.

Meki M (2024), "Small firm investment under uncertainty: The role of equity finance," Oxford Department of International Development (ODID) Working Paper Series, University of Oxford.

Stiglitz J (1974), "Incentives and risk sharing in sharecropping," The Review of Economic Studies 41(2): 219–255.

Udry C (1994), "Risk and insurance in a rural credit market: An empirical investigation in northern Nigeria," The Review of Economic Studies 61(3): 495–526.