Prime examples of ‘natural resources’ are agricultural land, water resources, fossil fuels and other types of mining. Three crucial characteristics are common between various types of natural resources.[1]

- They are all “specific” factors of production that are fixed in their location of supply. For example, in contrast to labour or capital, reserves of crude oil cannot be moved from one location to another.

- Commodities obtained from natural resources tend to be homogeneous regardless of their origin, and as such, they are treated as standardised commodities. For example, crude oil products that feature the same quality grading can be used interchangeably at oil refineries.

- When these commodities are used as an input, it is difficult to substitute them. For example, the demand elasticity for refined oil is considerably low, meaning that its end-users can hardly substitute it with other sources of energy.

In commodity markets, there are often a small number of large MNEs that establish the connection between suppliers and consumers along the global supply chain. In agriculture, even large-scale farmers in developing countries are too small to overcome the logistical costs required to export their products. In mining and energy, the technological costs and risks associated with discovery and extraction limit the capacity of smaller firms to undertake investments. For these reasons, MNEs tend to exert large markdowns and extract substantial local rents, even though these companies might face low profit margins, because on the output side they operate in markets with homogeneous goods with low degrees of differentiation.

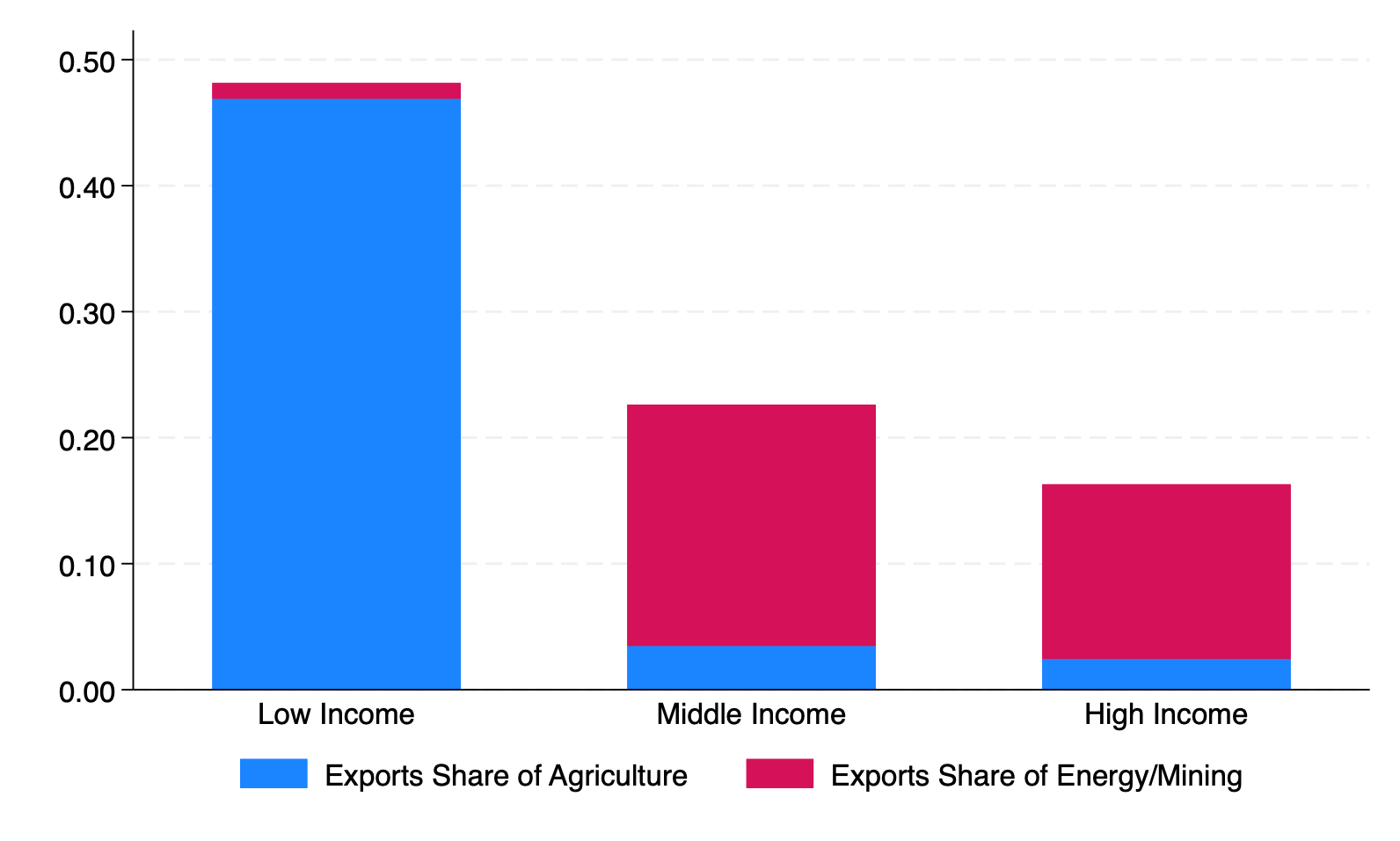

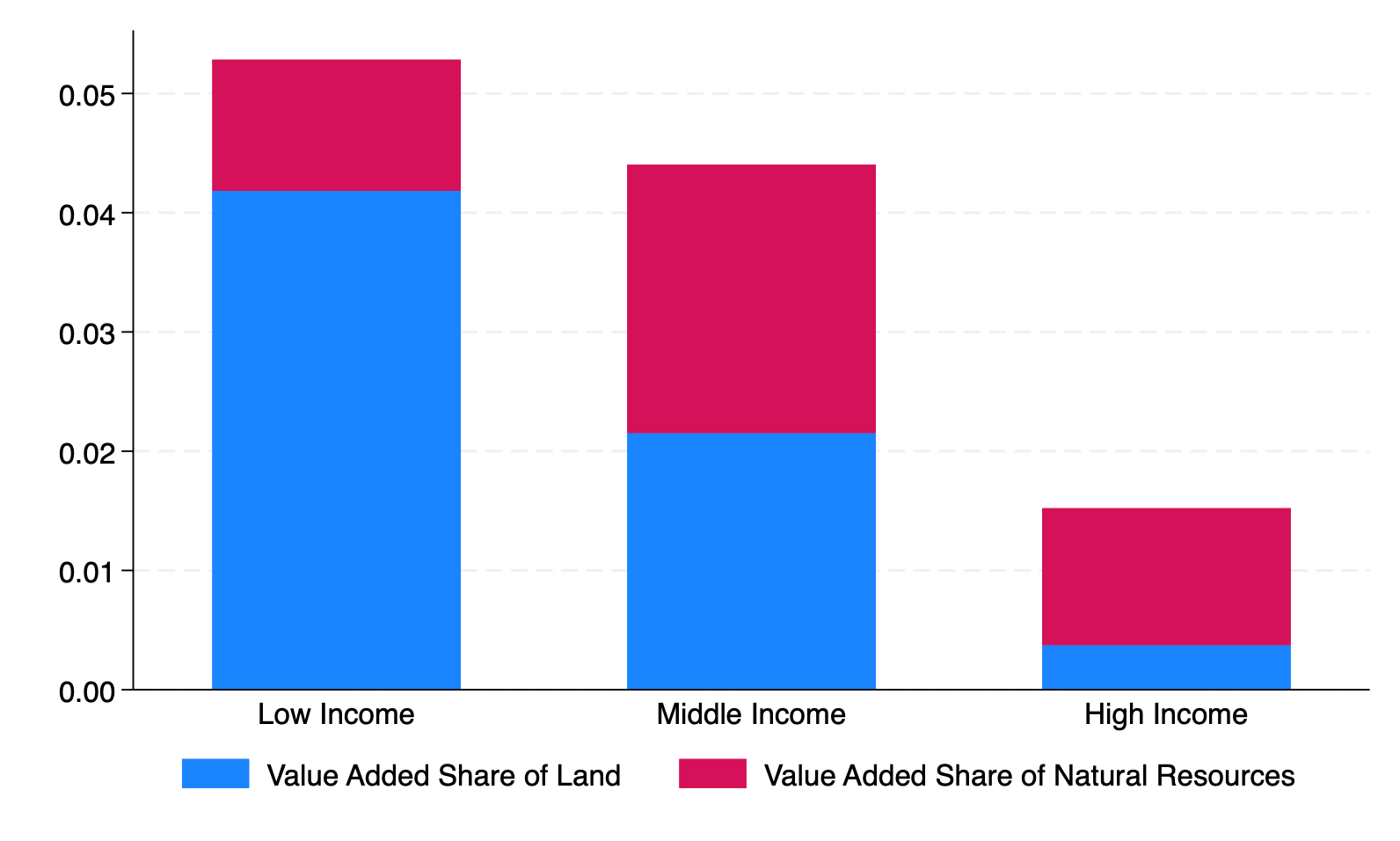

Natural resources are of significant macroeconomic importance for low- and middle-income countries. As shown by Figure 4-Panel (a), the Agriculture sector accounts for more than 40% of total exports in low-income countries, whereas it accounts for less than 5% of total exports in middle- and high-income countries. In contrast, the Energy & Mining sector generates a particularly large share of export revenues in middle-income countries. Panel (b) turns to value added. Land and natural resources account for around 5% of total value added in low- and middle-income countries, whereas in high-income countries these shares are less than half as large.

Figure 4: Share of Natural Resources in Exports and Value Added

(a) Exports

(b) Value Added

(b) Value Added

Trade, MNEs, and natural resources

This section discusses the role of international trade, mediated by multinational enterprises (MNEs), in markets for natural resources. We discuss the quantitative literature on these issues, dividing our exposition into agriculture, mining, and energy.

Agriculture

MNEs play a crucial role in creating the global food supply chain by connecting farmers’ production from around the world to final consumers. There are currently a limited number of MNEs establishing this connection. This concentration translates into significant monopsony power vis-á-vis farmers, who are numerous in each region and have limited options to sell their products abroad. A few recent studies have examined the consequences of this market structure, including Dominguez Iino (2023), Zavala (2022), and Dhingra and Tenreyro (2023). Results indicate that the “markdown”—i.e. the difference between the price MNEs offer to farmers for their products and the price MNEs obtain from final consumers net of processing costs—can be substantial. Specifically, Dominguez Iino (2023) estimates an export model of land use, in which farmers sell their products to trading firms operating in their region. Using his model, he studies the implications of deforestation policies in South America. He shows that markdowns are higher in frontier regions since a lower number of trading firms operate there. Consequently, trade policies that increase the market price of agricultural products have a limited impact on farm-gate prices in frontier regions where deforestation is higher. In a similar vein, Zavala (2022) develops and estimates a land use model of trade, which he uses to show that farmers in Ecuador receive only half of their marginal revenue products. Using data from Kenya and a model of market microstructure, Dhingra and Tenreyro (2023) find that farmers selling to agribusiness firms are more exposed to variations in world prices than farmers selling to local traders. Accordingly, agribusiness firms absorb most of the gains from an increase in world prices. These results suggest that despite the economic importance of MNEs for exports, the share that they pay to farmers is too low from a social point of view.

International trade plays an important role not only in markets of agricultural outputs, such as soybean, corn, and rice, but also in markets of essential agricultural inputs, such as fertilisers, seeds, and machinery. Farrokhi and Pellegrina (2023) document that, on average across countries, two-thirds of agricultural inputs are imported. Their analysis indicates that welfare gains from trade in agricultural inputs are as large as those from trade in agricultural outputs. This is because global trade in agricultural inputs induces large shifts from low-yield, labour-intensive farming to modern, input-intensive technologies. These results, in line with findings from McArthur and McCord (2017), imply that trade in agricultural inputs can contribute substantially to the process of structural change in developing countries. Here again, MNEs have a strong presence, and often the same MNEs carry trade in both agricultural inputs and outputs, as documented by Hernandez et al. (2023).

Mining and fossil fuel energy

A key feature of the supply chain in the mining sector, ranging from petroleum to minerals and metals, is that production is a two-stage process. For instance, iron ore is extracted in the locations of mines before it is processed into steel products near the locations of demand. Extraction and processing of crude oil into refined oil products is another important example. The two-tier production and trade system in the oil industry is studied in Farrokhi (2020), who shows that securing supply in the face of international logistical frictions plays an important role in shaping the global oil supply chain. In addition, he finds that trade-related shocks in oil markets typically generate distributional gains between crude oil producers and oil refineries. These are among the potential reasons for why MNEs are typically involved in the ownership of both stages of production in the oil industry, and by extension, potentially in other mining industries.

Within the mining sector, fossil fuel energy is the most prominent in terms of economic importance. In turn, the global energy sector is dominated by a handful of large MNEs, such as Shell, which coexist with state-owned companies, such as Saudi Aramco. MNEs in the energy sector are among the largest companies in the global economy. For example, in 2022, Shell’s revenue was almost equal to the GDP of South Africa. The striking size of the MNEs in the energy sector is a strong indicator of scale economies. Discovering new fields of oil and gas, improvements in extraction technologies, or building oil refineries require huge investment costs, which are justified only when production occurs at scale. Consequently, MNEs in the energy sector tend to operate in many countries, not only where demand for energy is large but also where the energy reserves are located. As such, MNEs bring investments and advanced technologies to energy-abundant countries that otherwise lack these resources, resulting in large profits that are divided according to negotiated contracts between the two parties. Existing research still provides, however, limited insights about which factors drive the partition of profits by these firms.

Policy implications and next steps

Natural resources can generate important streams of income in developing countries. MNEs can play a critical role in the materialisation of these gains by bringing technology, investment, and means of integration with the global supply chain. There are, however, important concerns regarding the potentially adverse effects of MNEs in local economies. MNEs can exacerbate existing domestic market failures, such as the overexploitation of natural resources such as forests, water, and fisheries. Hertel and Baldos (2016) and Farrokhiet al. (2023) discuss the implications of trade integration policies on ecosystems and deforestation. Another major concern is the extent to which the gains from trade and investment are shared with local economies. Considering both benefits and costs of MNEs in developing countries, the most effective policies appear to be those that promote the growth of MNEs as part of a comprehensive strategy, which includes addressing local market distortions and improving distributional inefficiencies.

Research on multinational production in the area of natural resources occupies a surprisingly small part of the literature. Researchers are constrained by restricted access to detailed information on MNEs in the agriculture and energy sector. In some datasets, researchers do not have access to the information on the largest MNEs, since the identity of these firms would be revealed by their uniquely large size. In the area of natural resources, however, a detailed study is not conceivable without information on these large MNEs.[2] Lifting these barriers will spur research on MNEs and natural resources.

The literature on multinational production has recently made significant progress by developing new methods to take models to the data. There is, however, substantial scope for progress in terms of modelling economic features that are ubiquitous in markets of natural resources. These features include, for example, oligopoly and market power, the investment decisions and strategies for expanding supply chains under uncertainty, and optimal policy design to maximise the potential benefits of MNEs where they are heavily involved in commodity markets. The literature has recently started to assemble datasets and develop tools to tackle some of these issues. Looking ahead, studying the economics of MNEs in natural resource markets, empirically, theoretically, and from a policy point of view, appears to be a promising avenue of research.

Institutions, MNEs, and extraction sectors

MNEs in the natural-resource extraction sector, from oil giants to smaller coal mining companies, are often viewed unfavourably by the general public. They are criticised for their disregard for the environment, involvement in political corruption and the undermining of good governance. Some economists also argue that they crowd out other sources of growth and development, such as manufacturing.

This section reviews recent evidence on the links between the activity of MNEs in natural resource extraction sectors and development.

Dutch disease?

Resource extraction, most often involving foreign MNEs, has been found to be associated with slower growth, corruption, and violence across developing countries (van der Ploeg 2011). A major concern has been the crowding out of the manufacturing sector by expanding resource-extraction activities. This displacement can occur as large resource windfalls lead to currency appreciation and decreased competitiveness, but it can also occur at the local level, as large mining firms, often foreign-owned, push local wages and other costs up, as they require vast amounts of public goods such as water, electricity, transport infrastructure, and land, on top of competing for educated workers. De Haas and Poelhekke (2019) looked at more than 25,000 firms in nine emerging economies, from Chile to Indonesia, using data from the World Bank and the EBRD’s enterprise surveys, and found that manufacturing firms located within 20km of industrial mines faced increased business constraints. Using ORBIS data, they confirmed that industrial mining reduced the size of nearby manufacturing firms. This suggests that industrial mining by multinationals may indeed crowd out manufacturing, which is often considered a source of growth and development.

A related question is whether FDI in natural resources crowds out other sources of FDI, notably in manufacturing and services, inhibiting economic diversification. Using detailed data on Dutch FDI available from the Netherlands’ Central Bank, Poelhekke and van der Ploeg (2013) found non-resource FDI declined, both in the short and long run, in countries that begin to export resources for the first time. They also found that doubling resource rents resulted in a 12.4% decrease in non-resource FDI and that this reduction was not compensated by increases in resource FDI, resulting in a 4% decline in aggregate FDI during resource booms. Toews and Vézina (2022) on the other hand suggested that oil and gas discoveries, specifically those of giant fields, which can be attributed to luck and generate substantial news shocks, can trigger FDI bonanzas. Across developing countries, they documented a 56% surge in FDI in the two years following a significant discovery, using data on individual FDI projects available from fDiMarkets (Financial Times). They observed this upswing in sectors such as manufacturing, retail, services, and construction, not just in extractive industries. They document one such FDI bonanza that occurred in Mozambique in 2016, and find that every new FDI job led to an additional 4.4 jobs locally, with 2.1 of them being formal jobs. Natural resource discoveries may thus provide a window of opportunity to attract FDI, diversify economies, and create jobs. However, as discussed below, the harmful political forces often associated with natural resource extraction may limit these potential benefits.

Governance

The relationship between mining MNEs and governance is a complex one. On the one hand, the quality of national institutions affects oil and gas explorations by MNEs. On the other hand, MNEs may pay bribes and work with rebel groups, leading to a deterioration of governance.

To examine the effect of institutions on oil and gas investment, Cust and Harding (2020) looked at exploration activities in regions along countries’ borders. Borders in the developing world are often arbitrary, sometimes even straight lines that cut through geological basins. They were not shaped by geography, which can be very similar on both sides of the borders, yet the quality of governance can shift abruptly on either side. These differences influence the decision of MNEs on where to explore for oil and gas, even when the likelihood of resource discovery is the same on both sides. Using data on more than 20,000 exploration wells across 88 countries from Wood Mackenzie’s Pathfinder database, they observe double the amount of exploration drilling on the side of the border with good governance from 1966 to 2010. They also find major international oil companies to be most sensitive to institutional quality. The evidence suggests that MNEs prefer to locate in better-governed places; important elements of developing an oil field, such as investing in infrastructure, hiring labour and exporting oil may prove easier in these locations.

Brunnschweiler and Poelhekke (2021) suggest that institutional change in the oil sector also affects exploration and discoveries. They collected data on oil ownership regimes from 1867 to 2008 in 68 countries and found that foreign ownership of oil fields not only increases exploration activity, but also the chances of discovering oil and gas. Switching to foreign ownership can thus be akin to increasing one’s luck. However, foreign ownership of oil and gas assets is also associated with governance problems. Considering oil and gas fields in Nigeria, Rexer (2022) examined whether the ownership of assets affected output and local violence. He looked at episodes of divestment to local firms following a major policy reform in 2010, which gave Nigerian firms preferences in all oil and gas asset transactions. Using a dataset of 314 active oilfields, he found that involving local firms resulted in increased production, and most strikingly, it led to a 45% reduction in incidents of oil theft by gangs, and decreased fatalities resulting from violent conflicts. Analysing news media reports on government law enforcement raids, he suggested this decrease was because divestment to local firms led to an increase in law enforcement actions targeting the illegal oil sector. Foreign ownership of oil and gas assets may thus also be linked to violence.

Conflict and violence

There is a large body of research linking mining MNEs to violence and conflict. Berman et al. (2017) for example looked at the relationship between the locations of mines, most often owned by foreign companies, and violent events across Africa, using data on violent events from ACLED. They found that violent events were much more likely to occur in locations in proximity to mines, and even more so when the mined commodity price was high. They find that the likelihood of violence, such as riots and organised battles, goes from 16.9% to 22.5% in mining areas when the mineral price increased by one standard deviation. One illustrative example they provide is that of the relationship between AngloGold Ashanti, a mining company headquartered in Johannesburg, and the Nationalist and Integrationist Front, a violent rebel group in the Democratic Republic of Congo, whereby the mining company paid bribes and worked with the rebel group in order to facilitate their mining operations. Sonno (2020) also looked at the relationship between MNEs and conflict across locations in Africa, using data from Bureau van Dijk. He finds that it is only land-intensive MNEs, which include mining firms, that are associated with conflict. In other words, foreign mining companies do seem to be associated with increased local violence in Africa. Using various datasets on social conflicts, protests, and riots, as well as three private repositories of mining data, Christensen (2019) also finds that the probability of protests and riots roughly doubles in African localities receiving new mining investments, where 75% of mining investment projects are from companies from Australia, Canada, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States. He does not find increases in rebel activity, which is one of the mechanisms put forward by Berman et al. (2017).

Corruption

There is also evidence that MNEs can exacerbate corruption at the local level. Knutsenet al. (2017) match 496 industrial mines in Africa, which are mostly owned and operated by Canadian, Australian, and British companies, with more than 90,000 individuals who took the Afrobarometer survey. This survey gathers public opinions on various issues including democracy and experiences with corruption and bribery. They find that, while companies prefer locating mines in less corrupt areas, bribe payments increase substantially in areas around mines, after mines open. Their back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that, among the 18 million living within 50 km of inactive mines in 2000, 700,000 were paid a bribe due to mine openings.

Environment

Industrial mines can also damage the environment and have knock-on effects on agriculture. This effect is analysed by Aragon and Rud (2016) in the context of industrial gold mining in Ghana, where many mines are operated by MNEs in the vicinity of fertile agricultural lands where crucial cash crops, like cocoa, are grown. They find that pollution by gold mines - which includes air pollutants from using heavy machinery and smelters, and also chemicals like cyanide and heavy metals carried by surface waters - to be associated with a decrease in farm productivity. Farmers within 20km of gold mines saw their crop yields decline and total productivity drop by around 40% between 1997 and 2005, relative to other farmers located elsewhere. Oil and gas exploration can also lead to environmental degradation in the form of forest loss. Cust et al. (2023) combine global satellite data on forest cover with data on more than 3,000 exploration wells across 55 countries and 396 different companies and find that exploration wells lead to an additional clearance of around 6 hectares over twelve years. While they find that better public governance lowers the forest loss effects of drilling, they find no indication that stronger corporate governance practices by MNEs are associated with lower forest loss.

Local impact

FDI in natural resources is not always bad for local development. Foreign investment in the extractive sector has also been found to promote growth at the local level. Bunte et al. (2018) examine the evolution of remotely-sensed nighttime lights across locations around the allocation of 557 natural resource concessions in Liberia. They find that investments in mining, particularly in iron-ore projects, exhibit positive growth effects, whereas agricultural and forestry investment projects do not. They also find that Chinese investment projects, not American, drive these growth effects. Aragon and Rud (2013) looked at how a large mine in Peru, Yanacocha, of which more than 50% is owned by a US mining company, affected local wages and poverty. Using household survey data, they compared areas close to the mine to similar locations further away and found that the expansion of mining operations led to a reduction in poverty rates as well as increased consumption. These positive local effects of foreign investment can have a long-lasting impact. Méndez and Van Patten (2022), for example, look at areas where the United Fruit Company, now Chiquita, was given land concessions around 100 years ago to grow bananas, and compare living standards in those areas today to those in other similar locations across Costa Rica. They find long-lasting effects and improved health, education, and housing, and attribute these outcomes to the investment in local infrastructure and amenities. While the evidence here suggests that extractive MNEs can have persistent positive effects locally, it does not address the deterioration in governance associated with being a ‘Banana Republic’ and their effects on countries’ long run development trajectory. In a similar study, Lowes and Montero (2021) analyse how rubber concessions granted by King Leopold II of Belgium to private companies in the north of the Congo Free State, often to Belgian MNEs, affected long-run development. The arbitrarily defined borders of these concessions allowed the authors to compare similar areas on both sides of the concessions and attribute differences in development outcomes to the effect of concessions’ indirect rule and violence. They find that historical exposure to rubber concessions lead to significantly poorer outcomes in education, wealth, and health. They also find that village chiefs within the former concessions provide fewer public goods, in line with extraction by foreign MNEs leading to a deterioration of governance in the long run. But they also find that individuals within the concessions exhibit higher levels of trust, cohesion, and support for income sharing, suggesting that culture may act as a substitute for institutions in colonial resource-extraction regimes. Different types of foreign investment and local governance structure may thus lead to very different development outcomes in the long run.

Policy implications and next steps

Economists have long been worried about the effect that natural resources can have on developing countries. There is convincing evidence that MNEs in the extractive sector are linked to corruption, violence, and environmental degradation in developing countries. Their activities may also crowd out those of nearby manufacturing firms. Yet, FDI can also bring positive local development impacts, especially in boom times. Large mines can spur local economic activity and reduce poverty. Large oil and gas discoveries can bring in waves of FDI which can be linked to infrastructure investments, creating jobs and generating long-lasting effects. Nevertheless, when a country discovers gold or oil, the right policies are required to ensure the benefits are fully realised and that MNE involvement brings development. Based on field experiments in Mozambique, Armand et al. (2020) suggest that providing citizens with information about substantial oil and gas discoveries can increase local mobilisation and decrease violence, and thereby counter the resource curse. Monitoring MNE corruption in their origin countries is also important. Christensen et al. (2024) show that enforcing the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in the mid 2000s led to higher local growth in areas around extraction facilities under US jurisdiction compared to other extraction sites, changing corporate behaviour.

References

Aragon, F M and J P Rud (2013), "Natural resources and local communities: Evidence from a Peruvian gold mine", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 5(2): 1–25.

Aragon, F M and J P Rud (2016), "Polluting industries and agricultural productivity: Evidence from mining in Ghana", The Economic Journal 126(597): 1980–2011.

Armand, A, A Coutts, P C Vicente, and I Vilela (2020), "Does Information Break the Political Resource Curse? Experimental Evidence from Mozambique", American Economic Review 110(11): 3431–53.

Berman, N, M Couttenier, D Rohner, and M Thoenig (2017), "This Mine Is Mine! How Minerals Fuel Conflicts in Africa", American Economic Review 107(6): 1564–1610.

Brunnschweiler, C N and S Poelhekke (2021), "Pushing one’s luck: Petroleum ownership and discoveries", Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 109: 102506.

Bunte, J B, H Desai, K Gbala, B Parks, and D M Runfola (2018), "Natural resource sector FDI, government policy, and economic growth: Quasi-experimental evidence from Liberia", World Development 107(C): 151–162.

Castro-Vincenzi, J (2023), "Climate hazards and resilience in the global car industry", Working Paper.

Christensen, D (2019), "Concession Stands: How Mining Investments Incite Protest in Africa", International Organization 73(1): 65–101.

Christensen, H B, M Maffett, and T Rauter (2024), "Reversing the Resource Curse: Foreign Corruption Regulation and the Local Economic Benefits of Resource Extraction", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 16(1): 90–120.

Cust, J and T Harding (2020), "Institutions and the Location of Oil Exploration", Journal of the European Economic Association 18(3): 1321–1350.

Cust, J, T Harding, H Krings, and A Rivera-Ballesteros (2023), "Public governance versus corporate governance: Evidence from oil drilling in forests", Journal of Development Economics 163: 103070.

De Haas, R and S Poelhekke (2019), "Mining matters: Natural resource extraction and firm-level constraints", Journal of International Economics 117(C): 109–124.

Dhingra, S and S Tenreyro (2023), "The rise of agribusinesses and its distributional consequences". Working Paper.

Dominguez Iino, T (2023), "Efficiency and redistribution in environmental policy: An equilibrium analysis of agricultural supply chains", Working Paper.

Doytch, N (2020), "Upgrading destruction? How do climate-related and geophysical natural disasters impact sectoral FDI", International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 12(2): 182-200.

Escaleras, M and C A Register (2011), "Natural disasters and foreign direct investment", Land Economics 87(2): 346–363.

Fally, T and J Sayre (2018), "Commodity trade matters", NBER Working Paper No. W24965.

Farrokhi, F (2020), "Global sourcing in oil markets", Journal of International Economics 125: 103323.

Farrokhi, F and H S Pellegrina (2023), "Trade, technology, and agricultural productivity", Journal of Political Economy 131(9): 2509–2555.

Farrokhi, F, E Kang, H S Pellegrina, and S Sotelo (2023), "Deforestation: A global and dynamic perspective", Working Paper.

Friedt, F L and A Toner-Rodgers (2022), "Natural disasters, intra-national FDI spillovers, and economic divergence: Evidence from India", Journal of Development Economics 157: 102872.

Gu, G W and G Hale (2023), "Climate risks and FDI", Journal of International Economics 146: 103731.

Hernandez, M A, A Espinoza, M L Berrospi, K Deconinck, J Swinnen, and R Vos (2023), "The role of market concentration in the agrifood industry", IFPRI Discussion Paper 02168.

Hertel, T W and U L C Baldos (2016), "Attaining food and environmental security in an era of globalization", Global Environmental Change 41: 195–205.

Jia, R, X Ma, and V W Xie (2022), "Expecting floods: Firm entry, employment, and aggregate implications", NBER Working Paper No. w30250.

Kanagaretnam, K, G Lobo, and L Zhang (2022), "Relationship between climate risk and physical and organizational capital", Management International Review 62(2): 245–283.

Knutsen, C H, A Kotsadam, E H Olsen, and T Wig (2017), "Mining and local corruption in Africa", American Journal of Political Science 61(2): 320–334.

Li, X and K P Gallagher (2022), "Assessing the climate change exposure of foreign direct investment", Nature Communications 13(1): 1451.

Linnenluecke, M K, A Stathakis, and A Griffiths (2011), "Firm relocation as adaptive response to climate change and weather extremes", Global Environmental Change 21(1): 123–133.

Lowes, S and E Montero (2021), "Concessions, Violence, and Indirect Rule: Evidence from the Congo Free State", The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136(4): 2047–2091.

McArthur, J W and G C McCord (2017), "Fertilizing growth: Agricultural inputs and their effects in economic development", Journal of Development Economics 127: 133–152.

Méndez-Chacón, E and D Van Patten (2022), "Multinationals, monopsony, and local development: Evidence from the United Fruit Company", Econometrica 90(6): 2685–2721.

Neise, T, F Sohns, M Breul, and J R Diez (2022), "The effect of natural disasters on FDI attraction: A sector-based analysis over time and space", Natural Hazards 110: 999–1023.

Pankratz, N and C Schiller (2021), "Climate change and adaptation in global supply-chain networks", Proceedings of Paris December 2019 Finance Meeting EUROFIDAI-ESSEC, European Corporate Governance Institute–Finance Working Paper 775.

Poelhekke, S and F van der Ploeg (2013), "Do Natural Resources Attract Nonresource FDI?", The Review of Economics and Statistics 95(3): 1047–1065.

Rexer, J (2022), "The local advantage: Corruption, organized crime, and indigenization in the Nigerian oil sector", Working Paper.

Sanna-Randaccio, F and R Sestini (2012), "The impact of unilateral climate policy with endogenous plant location and market size asymmetry", Review of International Economics 20(3): 580–599.

Sautner, Z, L Van Lent, G Vilkov, and R Zhang (2023), "Firm-level climate change exposure", Journal of Finance 78(3): 1449–1498.

Sonno, T (2020), "Globalization and conflicts: the good, the bad and the ugly of corporations in Africa", CEP Discussion Papers dp1670.

Toews, G and P-L Vézina (2022), "Resource Discoveries, FDI Bonanzas, and Local Multipliers: Evidence from Mozambique", The Review of Economics and Statistics 104(5): 1046–1058.

van der Ploeg, F (2011), "Natural resources: Curse or blessing?", Journal of Economic Literature 49(2): 366–420.

Wang, P, H Zhang, and J Wood (2021), "Foreign direct investment, natural disasters, and economic growth of host countries", in Chaiechi, T, ed. Economic Effects of Natural Disasters, Academic Press.

Yang, D (2008), "Coping with disaster: The impact of hurricanes on international financial flows, 1970-2002", The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 8(1).

Zavala, L (2022a), "Unfair trade? Market power in agricultural value chains", Working Paper.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.