A programme constructing new rural roads in India increased bank lending, particularly to previously excluded communities, with new financing put towards productive uses

Investments in public infrastructure, especially roads, play a pivotal role in national development and economic growth, particularly in emerging economies. A growing body of evidence estimates the impacts of new and improved road infrastructure, such as China’s new national trunk roads (Banerjee et al. 2020, Faber 2014), new railroads in colonial India (Donaldson 2018), rural roads in India (Adukia et al. 2020, Asher and Novosad 2020), national highway upgrades in India (Naaraayanan and Wolfenzon 2023) and highways in the US (Duranton and Turner 2012) – this evidence is summarised in VoxDev’s forthcoming VoxDevLit on Land Transport Infrastructure. They show that such improvements facilitate the movement of goods and people across space, increase lending to firms, stimulate output growth, and enhance economic welfare (Donaldson 2015).

A common assumption among policymakers and financial economists is that once roads are built, financing will follow, facilitating the optimal utilisation of new productive opportunities resulting from improved connectivity. These improvements in road connectivity are concentrated in rural and agrarian economies, where nearly 3.5 billion people, approximately half of the world's population, reside. These areas are often characterised by poverty and face chronic financing challenges, marked by the absence of formal financial institutions. Instead, residents there typically rely on informal moneylenders, who are often unreliable and charge usurious interest rates. This raises a fundamental question: if roads are built, will financing follow? Furthermore, even if financing follows infrastructure improvements, the question arises: who will benefit? Will it primarily favour the relatively rich villagers, or will it extend to the poorer villagers, who were earlier excluded from formal finance?

How can the impacts of infrastructure be estimated?

These questions hold significant relevance for policymakers but have received limited scrutiny in existing research. One reason behind this gap is that infrastructure is not randomly placed across regions. Any observed economic growth in a region that receives roads, compared to one that does not, cannot be exclusively attributed to the infrastructure investment. The improvements may also stem from changes in other concurrent environmental or policy factors. Therefore, research must find a way to compare regions that are similar in all aspects except for their infrastructure development. Fortunately, the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) programme in India presents a nearly perfect setting to address this challenge.

The PMGSY programme prioritises building roads in villages above explicit population thresholds at a point in time. For example, a village with a population right above a round figure, say 1000, was to be prioritised to receive a road, relative to a village with a population right below 1000. Thus, a comparison between two villages that are right above (say 1020) and right below (say 980) the threshold, but are otherwise similar in geographic and economic factors, allows us to examine the effect of receiving a new road on financing, while holding other factors constant. In our recent research (Agarwal, Mukherjee, and Naaraayanan 2023) we take advantage of this setting to examine the impact of the PMGSY programme on private financing to households. The analysis is made possible by our access to a proprietary dataset on rural bank accounts from one of India's largest private lenders (referred to as “the bank” hereafter) on loans made. Our data comes from the coastal district of Ganjam in the eastern state of Odisha, and from the mountainous districts of Tehri Garhwal, Uttarkashi, Chamoli, and Garhwal in the northern state of Uttarakhand.

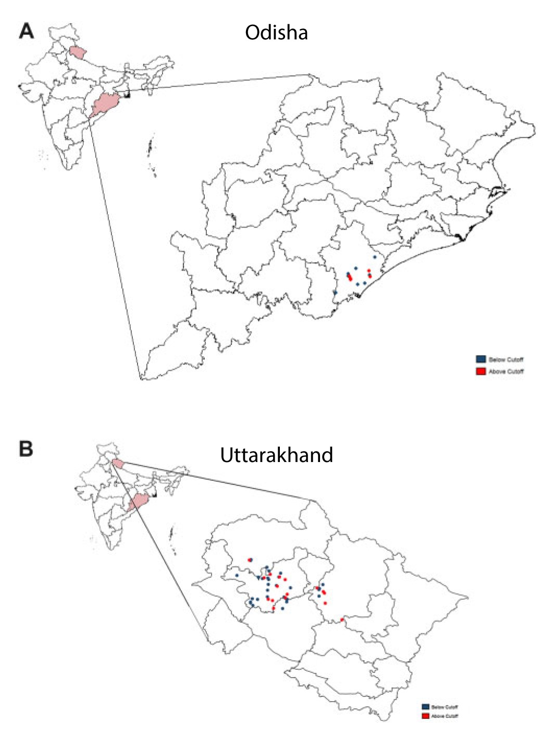

Figure 1: Distribution of unconnected villages by population cutoff

To start, we present three pieces of evidence on our key identifying assumption, that even if selection into road connectivity could be determined by many factors in general, these factors are not likely to “jump”, or in other words change discontinuously, at the population thresholds used to prioritise road building. First, we show that there are no discrete jumps in population around the PMGSY thresholds of 500 and 1,000, indicating that population sizes were not manipulated to try and game the system. Second, we examine the geographic clustering of places more likely to receive roads vs. those that were less likely, and find that the above- and below-cutoff villages come from geographically proximate areas within each state (see, Figure 1). Third, we show that there are no discontinuities in baseline measures such as in the presence of schools, health centres, electricity, or a telegraph office, the distance from the nearest town, the percentage share of scheduled castes or tribes in population, and land irrigated.

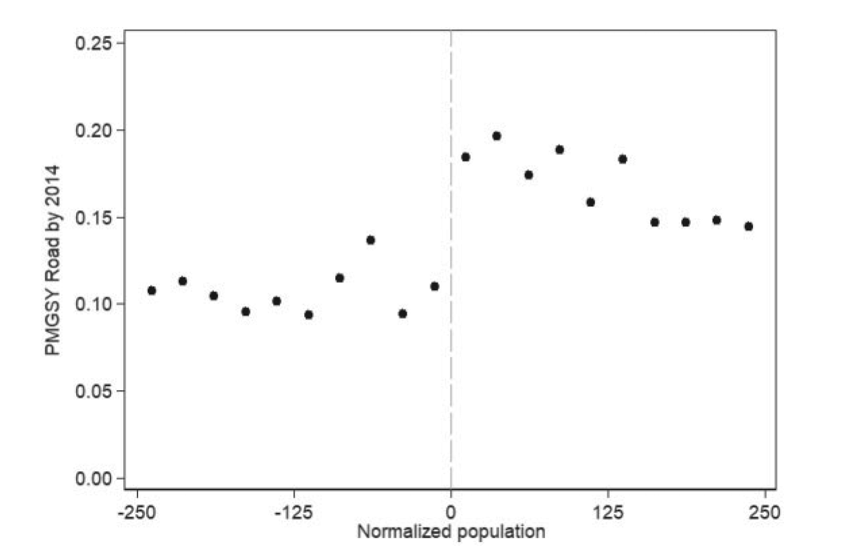

Importantly, we show that population cutoffs do predict road construction (see, Figure 2). Our sample period starts in 2009, when the bank started lending and all villages in our sample were unconnected. The estimates imply that by 2014, there is a 6.6- to 6.8-percentage-point increase in the probability for a previously unconnected village right above the threshold to receive a road compared to one right below the threshold, which shows that the villages above the population threshold are given priority to receive roads. The unconditional probability of getting a road is about 11–12%, this is about a 57–60% jump and is highly statistically significant.

Figure 2: First stage: Effect of road prioritisation on the probability of a road by 2014

How do roads affect lending?

In terms of the lending, by 2014, when we measured differences in loans outcomes, we find that the odds of our bank lending to someone from a given village is twice as high for villages above-cutoff as compared to those below. At the same time, the bank lends to 75% more borrowers in an above-cutoff village. Among the households that received loans, the loan amounts are 30-35% higher for those who lived in villages right above, versus below, the threshold. Overall, we find large financing responses to rural road connectivity.

Given the large response, it begs the question what these loans are used for. To answer this question, we partition the loan amounts based on whether the financing was provided for productive uses, such as business expansion, asset acquisition, and working capital needs, or other non-productive uses, such as consumption needs, weddings, and festival expenses. We find that, villages above the population threshold (relative to below) received significantly higher loan amounts for productive uses of all types, and in particular, this difference is strongest economically for microenterprise loans and crop loans. This is consistent with policymakers' views on benefits owing in the form of opening or expansion of small businesses like village grocery shops (Agarwal et al. 2023), or changing crop patterns from subsistence to more profitable market-based crops. Further, we also find lower loan amounts for non-productive uses.

Next, we examine the distributional consequences of rural road connectivity. We focus on individual-level demographic differences and identify the segment of population that benefits most from road connectivity. We find that individuals with fewer assets benefit more in terms of receiving higher loan amounts. That is, people who did not have collateralizable assets like a house or land can now borrow more. This is consistent with the view that new roads release collateral constraints and improve financial inclusion for those who lack traditional collateralizable assets.

Lastly, we present macro evidence that financing is important to realize the benefits of connectivity, and that such financing indeed follows rural road-building well beyond our baseline bank-loan sample. Nevertheless, access to credit in rural areas remains significantly limited in India and other developing nations, and the expansion of banking branches does not appear to be responsive to roads. Consequently, there is still much work to be done.

Policymakers often talk about trickle down benefits of rural road connectivity for households, such as allowing farmers to shift to cash crops, move goods produced in villages to marketplaces, employment generation within villages, etc. Our results have important implications for understanding such trickle-down benefits of building large scale infrastructure and its distributional consequences. Our research is one of the first explorations of whether financing responds to productivity changes arising from large-scale rural road-building initiatives. In doing so, our research provides first estimates of the impact of road connectivity on access to, and productive utilisation of, formal financial services.

References

Adukia, A, S Asher, and P Novosad (2020), “Educational investment responses to economic opportunity: evidence from Indian road construction.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(1): 348-376.

Agarwal, S, A Mukherjee, and S L Naaraayanan (2023), “Roads and loans,” The Review of Financial Studies, 36: 1508–1547.

Agarwal, S, P Ghosh, A Mukherjee, and SL Naaraayanan (2023), “Rural roads, small business creation, and the gender-gap in entrepreneurship,” Working Paper.

Asher, S, and P Novosad (2020), “Rural roads and local economic development,” American Economic Review, 110: 797–823.

Banerjee, A, E Duflo, and N Qian (2020), “On the road: Access to transportation infrastructure and economic growth in China,” Journal of Development Economics, 145: 102442.

Donaldson, D (2018), “Railroads of the Raj: Estimating the impact of transportation infrastructure,” American Economic Review, 108(4-5): 899–934.

Duranton, G, and M A Turner (2012), “Urban growth and transportation,” Review of Economic Studies, 79(4): 1407–1440.

Faber, B (2014), “Trade integration, market size, and industrialization: Evidence from China's National Trunk Highway System,” Review of Economic Studies, 81(3): 1046–1070.

McCrary, J (2008), “Manipulation of the running variable in the regression discontinuity design: A density test,” Journal of Econometrics, 142(2): 698–714.

Naaraayanan, S L, and D Wolfenzon (2023), “Business Group Spillovers,” The Review of Financial Studies, Forthcoming.