New data from 99 developing countries challenges conventional wisdom in development policy. People whose labour has higher returns at home are more likely to migrate.

In economic research, there are two competing theories about what drives migration decisions, and therefore who we would expect to migrate. One theory views migration as a form of investment in human capital, as pointed out by Gary Becker (1964, p. 1). Migration carries large direct, indirect, and opportunity costs today, but it can bring large and sustained benefits tomorrow (Clemens et al. 2019). For the same reason that higher-income people invest more in university education, we might expect higher-income people to invest more in migration (Grogger and Hanson 2011). A corollary is that economic development, by raising incomes, should allow more investment in migration. This human capital model predicts ‘positive selection’ – higher-income people are more likely to emigrate.

Yet many labour economists have modelled the migration choice fundamentally differently. A popular model of migration equates the decision to migrate to occupation choice (Roy 1951). In such a model, the poorest from poor and unequal developing countries have the most to gain from migration. This assumption, sharply at odds with the human capital model, predicts that higher-income people are less likely to leave (negative selection) and economic development should reduce emigration – in academic terms, migration is an ‘inferior good’ and therefore demand for migration falls as income rises.

Which economic model is more successful in describing migrants from developing countries?

It matters enormously to policy. Aid donors to low- and lower-middle-income countries continue to pour billions of dollars into the idea that development necessarily and obviously reduces migration. And whether migrants are negatively or positively selected, i.e. on relatively lower or higher incomes, shapes the effect of policies that restrict migration on productivity and labour markets in migrant-destination countries.

But empirical evidence about the relationship between income and migration worldwide is scant, particularly because some characteristics which may influence income and thus migration decisions are hard to observe e.g. natural talent or risk tolerance.

Testing economic models of migration in 99 developing countries

In new research (Clemens and Mendola 2024), we use unprecedented worldwide data to challenge the textbook model of migration choice and the conventional wisdom in development policy. We measure the relationship between income and migration from data on nationally representative survey interviews with 653,613 adults in 99 developing countries.

This global survey, conducted by the Gallup Organisation, does not merely ask about the hypothetical wish to migrate. It proceeds to ask respondents whether they are planning to migrate in the next year - and if so, if they have taken costly steps to imminently migrate, like paying for passage. Evidence shows that reported migration planning or preparation, not just abstract wishes, correlates tightly with actual migration behaviour (Tjaden et al. 2019).

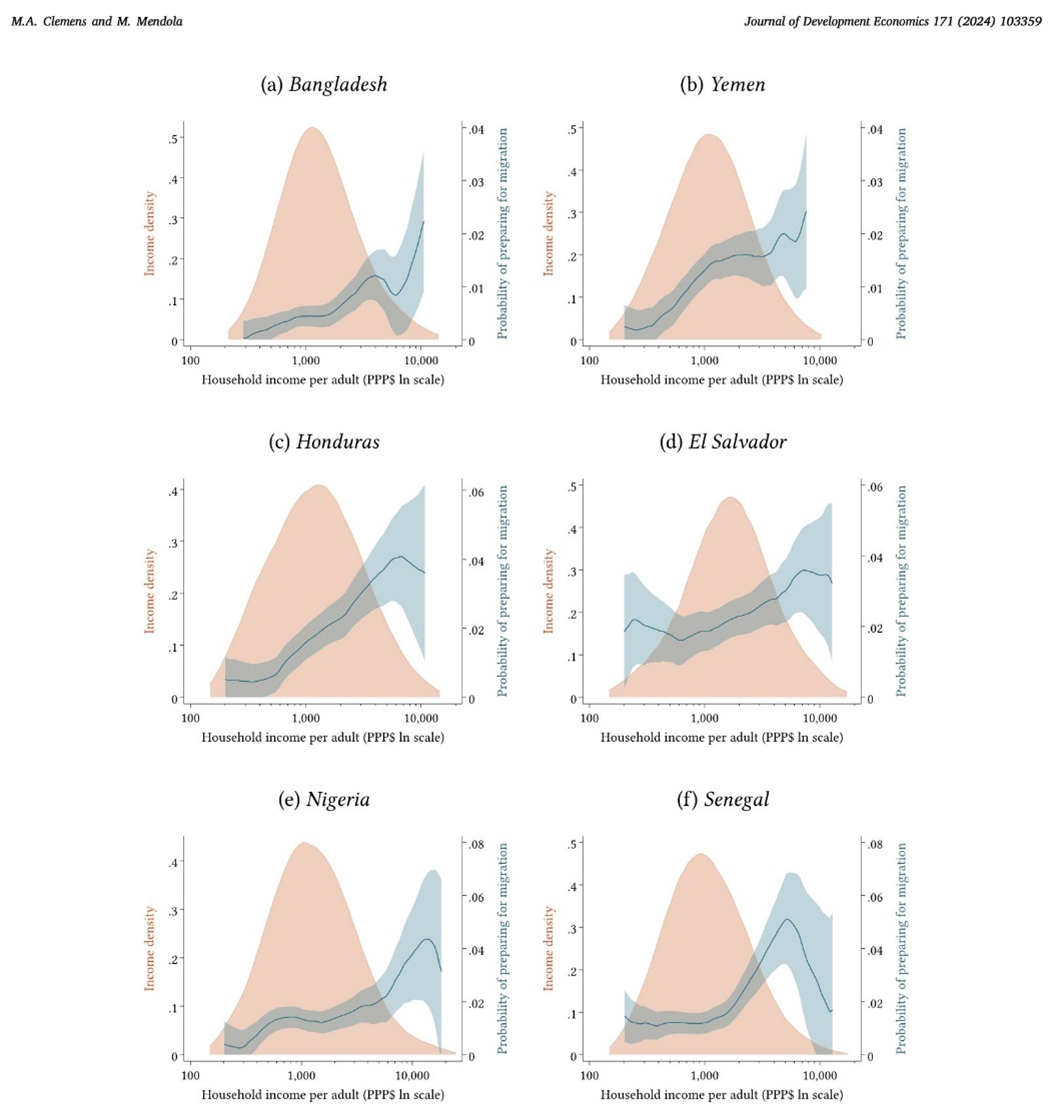

In Figure 1 we show that, in country after country, the fraction of people who are wishing, planning, and also preparing to migrate (in blue) generally rises across the income distribution (orange). This remarkably robust relationship is observed in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Figure 1: Active preparation to emigrate across the income distribution, selected countries

Notes: Data for individuals, pooled 2010-2015. Sample sizes: Bangladesh 7969; Yemen 9660; Honduras 5566; El Salvador 5874; Nigeria 6459; Senegal 5691.

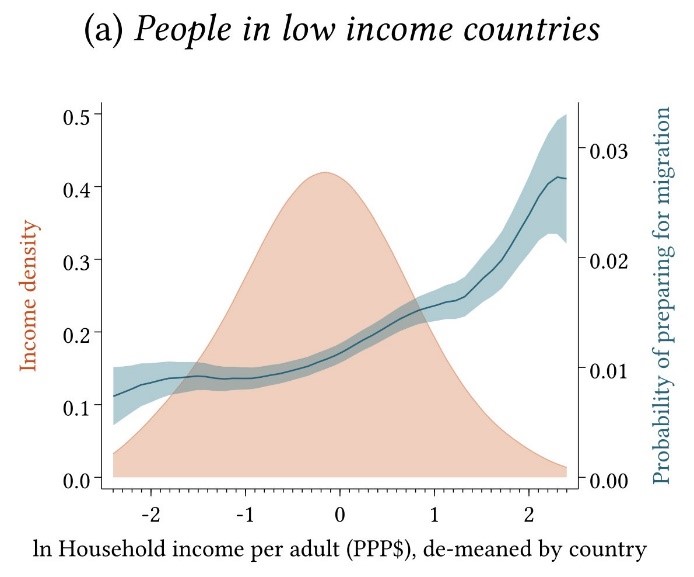

In fact, this pattern is systematic across the developing world. Figure 2 pools together all individual-level data for low-income and lower-middle income countries. The figure summarises interviews with 120,420 people in low-income countries on the left (Figure 2a), and 236,146 people in lower-middle-income countries on the right (Figure 2b).

Figure 2

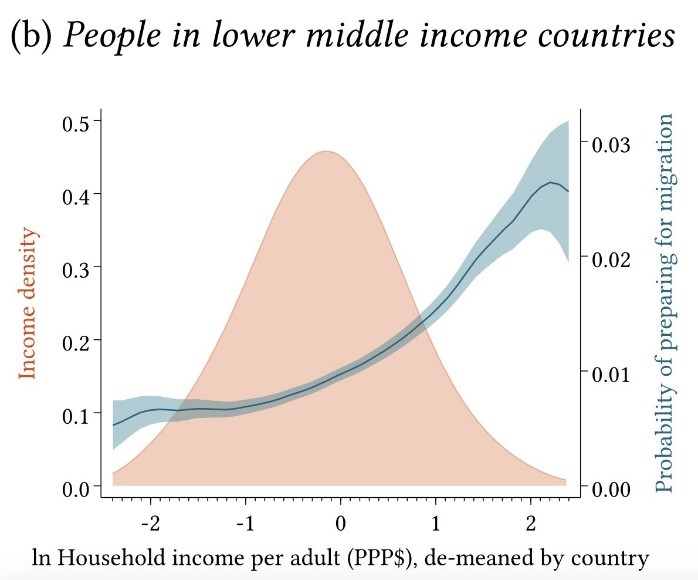

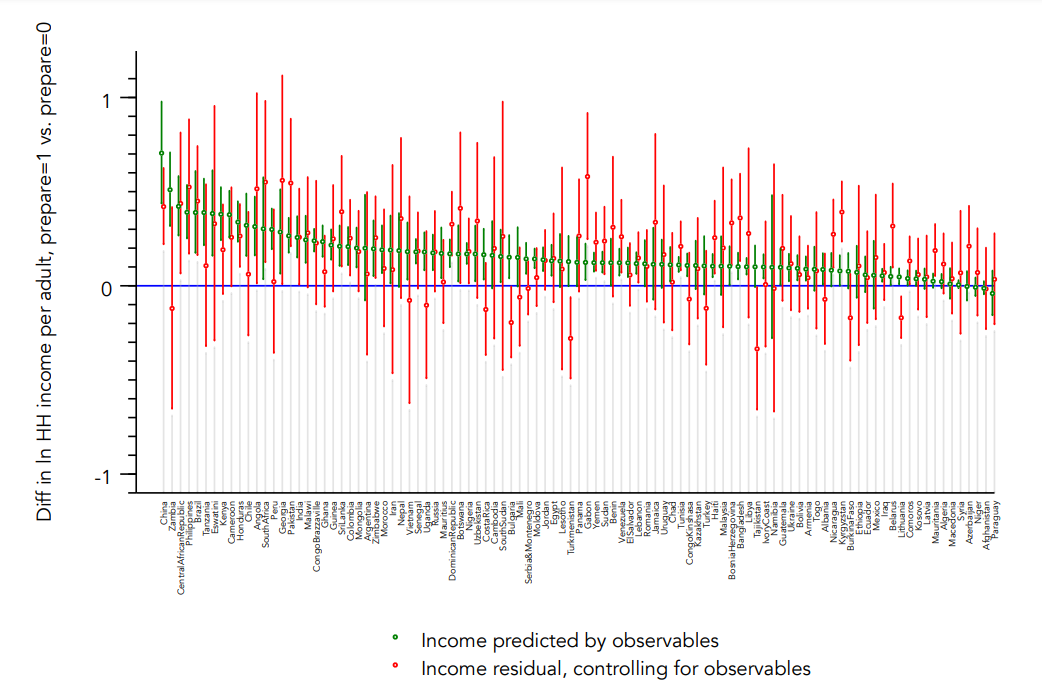

Country by country, Figure 3 reports the difference between average incomes among people who are about to emigrate and people who are not. Selection into emigration is positive in 93 out of 99 developing countries – those preparing to emigrate have higher income on average than those who are not.

Figure 3: Emigrant self-selection on overall determination of income.

Notes: Data for individuals, pooled 2010-2015. Vertical axis is the coefficient on an indicator for actively preparing to emigrate, where regressand is in household income per adult, and vertical line shows 95 percent confidence interval.

How do migration decisions depend on other factors, like education and talent?

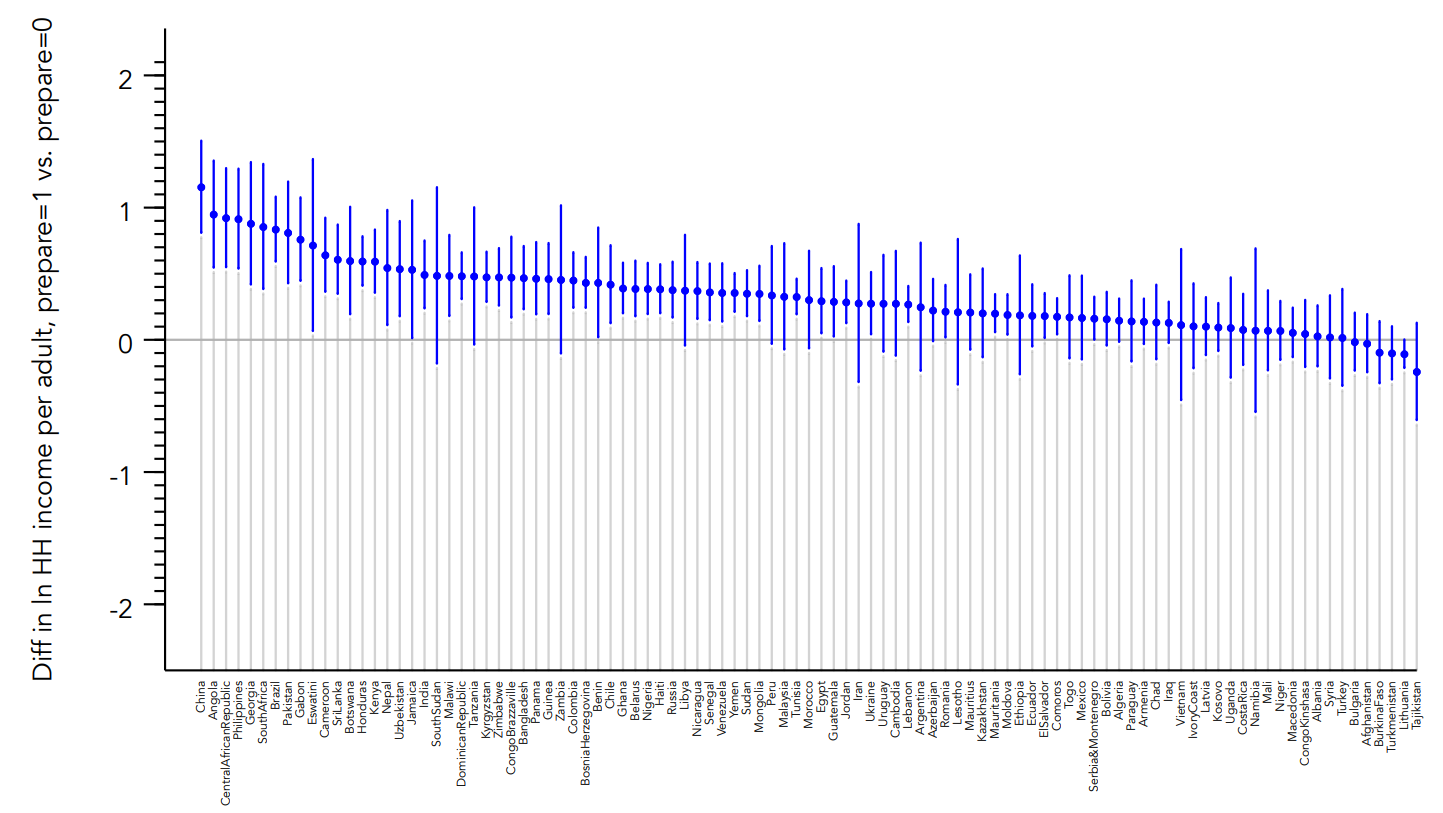

We then separate selection on income into determinants of income that are observable (like education) and unobservable (like talent). Selection is positive on observables in 95 out of 99 countries and positive on unobservable determinants of income in 85 out of 99 (Figure 4).

If we focus only on selection of migrants to rich-country destinations, like US/Europe/Australia, selection on income becomes much more positive. This is consistent with the idea that migrating to these countries is costlier among other factors and features of these destination markets.

Figure 4: Emigrant self-selection on unobservable income determinants

Notes: Data for individuals, pooled 2010-2015. Vertical axis is the coefficient on an indicator for actively preparing to emigrate, where regressand is household income per adult. Solid green circles (selection on observables) show coefficient when regressand is income predicted by observable traits: education, age, gender, and rural/urban origin of randomly selected adult respondent. Empty red circles (selection on unobservables) show coefficient when regressand is the income residual after controlling for those observable traits. Vertical lines show 95 percent confidence interval. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In other words, the defining stylised fact of migrant selection - across the developing world - is positive selection. People whose labour has higher returns at home are more likely to migrate.

Why does the data on migration clash with intuition?

The finding of generally positive selection is often greeted by savvy development practitioners, quite reasonably, with disbelief. If one interviews migrants from developing countries, they frequently report lack of economic opportunity as a central motive to migrate (e.g. Garver-Affeldt 2021). How, then, could greater opportunity at home fail to reduce migration? This reasoning can be deceptive: Those too poor to migrate do not become migrants, and thus are not interviewed. Rising incomes might have deterred some interviewed migrants from migrating; but rising incomes can also turn those unable to migrate today into people able to migrate tomorrow. The latter effect is ignored if we rely on evidence gathered from migrants, a textbook case of selecting on the dependent variable (here the choice to migrate).

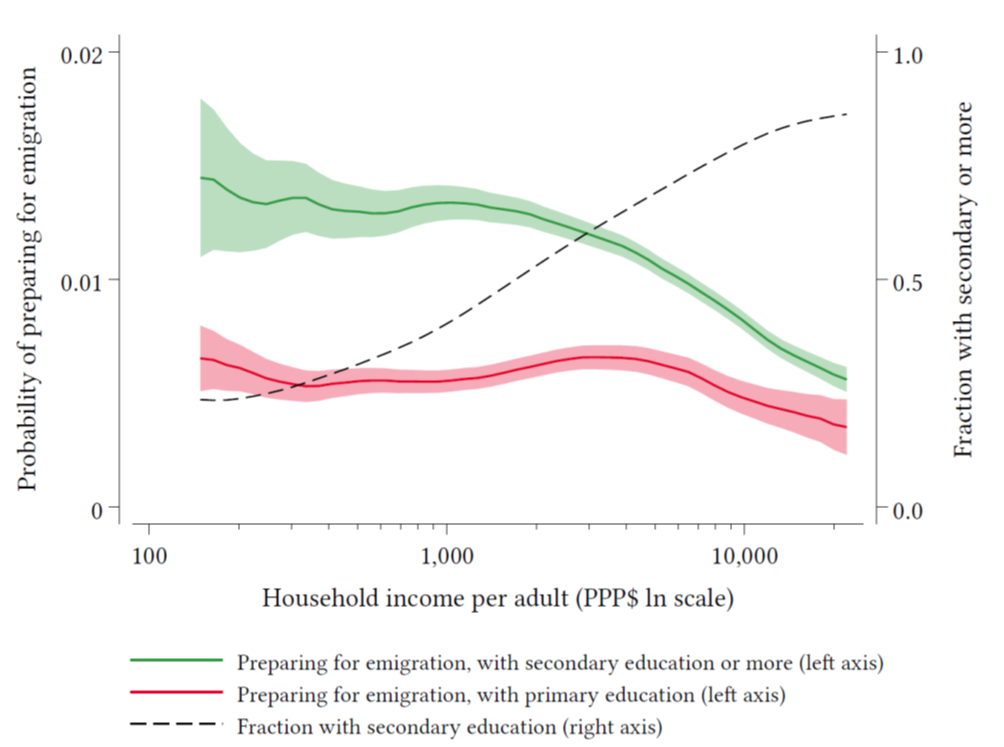

Direct observations can also trip us up in a different way. The relationship between earning opportunities in the home country and emigration can be positive for any given group of people - or even every single individual person - but still negative in the aggregate. The reason is the well-known logical fallacy of Simpson’s Paradox.

For example, suppose that people with high school education are more likely to emigrate than people without. And suppose that within these two specific groups, the effect of income on migration is negative, such that for both people with and without high school education, higher incomes reduce the tendency to emigrate. In the aggregate, income can nevertheless raise the tendency to emigrate because higher incomes typically cause more investment in education, shifting people to a higher-income group. Even if the relationship between income and migration is negative within specific groups, rising incomes can increase migration by shifting people into different groups.

Figure 5 uses our data to provide a snapshot of Simpson’s Paradox in the real world. Across all developing countries collectively, income and emigration correlate negatively within education groups, but income also shifts people into groups with higher education and higher emigration. The net effect is that for poor countries, rising aggregate incomes go hand-in-hand with rising aggregate emigration (Clemens 2020).

Figure 5

What have we learned about who migrates form developing countries?

Our results are compatible with a model in which typical developing countries behave, in the aggregate, as if higher incomes directly complement greater migration or investment in other things (like education) that complement migration. It is also compatible with a range of evidence, across the developing world, that increases in income cause migration to rise (e.g. Bazzi 2017, Molina et al. 2020, Gazeaud et al. 2023). The model of migration as resembling a costly human capital investment - not a simple occupational choice - is thus more useful for policymakers seeking to shape the real world.

References

Bazzi, S (2017), “The impact of migration barriers,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(2): 219–255. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20150548.

Becker, G (1964), Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, 1st ed., Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Clemens, M A, C E Montenegro, and L Pritchett (2019), “The place premium: Bounding the price equivalent of migration barriers,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 101(2): 201–213.

Clemens, M A (2020), “How economic development shapes emigration,” VoxDev, Sep. 21.

Clemens, M A, and M Mendola (2024), “Migration from developing countries: Selection, income elasticity, and Simpson’s paradox,” Journal of Development Economics, 171: 103359.

Garver-Affeldt, J (2021), “Migration drivers and decision-making of West and Central Africans on the move in West and North Africa: A quantitative analysis of factors contributing to departure,” Copenhagen: Mixed Migration Centre.

Gazeaud, J, E Mvukiyehe, and O Sterck (2023), “Cash transfers and migration: Theory and evidence from a randomized controlled trial,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 105(1): 143–157.

Grogger, J, and G H Hanson (2011), “Income maximization and the selection and sorting of international migrants,” Journal of Development Economics, 95(1): 42–57.

Molina Millán, T, K Macours, J A Maluccio, and L Tejerina (2020), “Experimental long-term effects of early-childhood and school-age exposure to a conditional cash transfer program,” Journal of Development Economics, 143: 102385.

Roy, A D (1951), “Some thoughts on the distribution of earnings,” Oxford Economic Papers, 3(2): 135–146.

Tjaden, J, D Auer, and F Laczko (2019), “Linking migration intentions with flows: Evidence and potential use,” International Migration, 57(1): 36–57.