How can researchers write accessible summaries of academic research? In this blog, I reflect on some key takeaways from editing approximately 350 VoxDev articles that summarise policy-relevant research in development economics.

VoxDev releases summaries of academic papers every weekday. These are written by researchers and we have a set of guidelines that we provide when commissioning articles. In this blog, I have summarised and expanded on these guidelines based on my own experience of editing approximately 350 VoxDev articles. The most important aspect of a paper summary is the underlying research itself, so some of the advice below won’t be suited to all projects, but hopefully it provides useful insights on how you can communicate your research to a policy audience.

What are the VoxDev style rules for articles?

We provide the following general advice to VoxDev authors on how to summarise economic research:

- The primary objective is the accessibility of economic research for non-technical, policy-oriented audiences. This can mean translating complex econometrics or theory in a manner that clearly conveys the core insights and policy implications.

- The article should reference the theory or empirical findings; it will be more rigorous than a newspaper opinion piece, but much more accessible than a journal article.

- The article should read like a research-based contribution to the broad policy debate on some issue, not like a press release or non-technical summary for a single article, even though many columns are clearly based on one paper.

- I.e. don’t jump straight into the research, and start by outlining the context with mention to a current policy debate or concern (more on this later).

- Structured to be accessible to readers, making strong use of clear, descriptive subheadings.

- Subheadings don’t just help the reader, they are important in helping google boost your article higher in search engine results!

- I really like the structure and use of subheadings in this VoxDev article on targeting aid after disasters.

Alongside this generic advice, we make some specific requests on what not to include, which I have included in a list at the end of the blog.

Pitching research findings at the right level: Not too broad, not too narrow

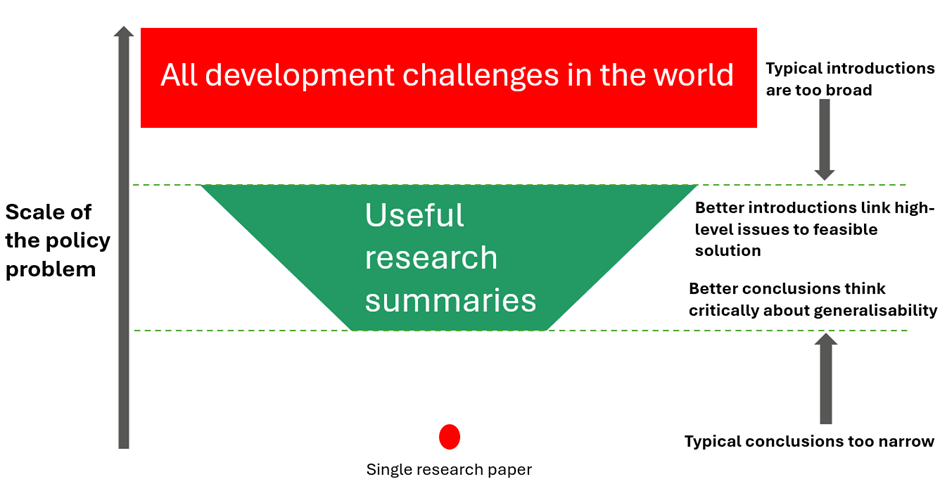

Most paper summaries begin with a broad overview of a topic before focusing on the specifics of the research design. First drafts of articles often start with impossibly broad introductions and then jump straight into the methodology and results, where the scope narrows considerably, before ending with a very specific conclusion.

It helps to think at a ‘mid-level’, which is closer to what is useful to policymakers. This requires two changes to the majority of paper summaries I see:

- Don’t jump from impossibly broad introductions straight into the methodology, i.e. try to pitch these issues at a level that is within target policymakers’ control.

- Don’t end impossibly narrow – even if the article is about a relatively specific study on a small intervention, think critically about how your results may apply elsewhere, and how much of the problem outlined in your introduction your research could solve.

As I have tried to illustrate in the figure below, there is a “useful zone” for paper summaries where feasibility (what a policymaker can control) and external validity (what a policymaker can take from your results to their own context) overlap.

Introducing your research to a non-academic, policy-oriented audience

Why should policymakers care about your paper? The best paper summaries first outline the importance of a policy issue, explore how it could feasibly be fixed, and think critically about how this links to the specific research paper being discussed.

Introductions should aim to provide context and highlight the importance of certain development issues, but if authors want to reach decision makers, they should consider the level at which decisions are made. This means linking high-level stats on, for example, global poverty or health outcomes, to your own specific study.

This recent post on digital humanitarian aid does a great job at moving incrementally from the big picture issue to their specific study.

Treading the fine line between overstating and understating your findings

Development economists, in general, are now more cautious in making grandiose policy prescriptions. The credibility revolution has turned this on its head, and fostered a focus on causality that has enabled research to better contribute to evidence-based policymaking.

However, one thing I have picked up in my time as editor is the unwillingness of economists to actually say, without caveats, what their research shows, or where they feel the evidence lies. There is a fine line to tread, but often it feels as if academics have been conditioned to undersell their research and couch conclusions in a large number of caveats.

This is not useful for a policymaker. If an article’s only conclusion is that a policy may, could, can, potentially, or might have an impact, it is not obvious what the next steps are from a policy perspective. This need not be the case when summarising high-quality economic research. When concluding, start with what you can confidently say, even if it is for a specific policy or context. Then think through what the caveats might be if a policy was implemented at a larger scale, for a different population, or with different contextual factors. Be explicit. Why might it scale effectively? What are some important context specific factors? What are similar places/areas this policy might work?

This is arguably both the hardest, and most useful, part of writing a paper summary. The conclusion of this article on climate adaptation does an excellent job of considering the circumstances in which an intervention providing emergency loans can effectively promote adaptation.

I would highly recommend this article by Mary Ann Bates and Rachel Glennerster on the “Generalisability Puzzle”, which discusses these issues in more detail, and provides a framework for thinking about external validity.

Put yourself in the shoes of a policymakers

Academics and policymakers want emphasis on different things. It is easier said than done, but if writing for a policy audience, really try to think through what you would want to know in their position.

For example, details about an intervention might bore fellow academics, but are crucial for a policymaker or practitioner trying to decide whether an intervention would be feasible in their context. The best summaries for policy audiences don’t gloss over implementation. For example, this article outlines the impacts of a school feeding programme in Colombia and clearly describes how this was implemented by the government.

I also find it useful when authors reflect on what happened after their research project. Was a policy continued or scaled up after their research? If not, do you know why?

First drafts tend to include excessive descriptions of models or robustness checks. These might be important for convincing academics but are confusing and unnecessary for non-academic audiences. This article on green trade policy by Allan Hsiao is a great example of how you can briefly outline why you are using a model, and what it achieves, without getting bogged down in the details.

Synthesising and communicating the key takeaways from previous economic research

We now have 12 VoxDevLits, which synthesise evidence across different research papers to establish where the weight of evidence lies on important questions in development economics.

Most articles have some level of synthesis when introducing a topic, or contextualising findings against previous research. When synthesising, try to capture the high-level takeaways of a broad body of research in a single sentence, rather than listing papers and their individual findings.

Often, when academics ‘synthesise’, they sit on the fence. Understandably, there is a reluctance to make broad sweeping statements if the evidence isn’t there, but academics are allowed to know things, and there are a growing number of topics where the weight of evidence does point in a specific direction.

What not to include: Stick to words and concepts that are used outside of academia

It never harms a summary of research to be as accessible as possible – you are only widening the pool of people who might be interested. Academics can always go to the paper for more details. For non-academics, an accessible summary is the only way they can understand and interact with your findings.

Here are some examples of common jargon used by economists, and the simpler synonyms I aim to replace them with:

Heterogeneity– Different effects on different groupsAny word before model– Just say you use a model and describe what it does as simply as possible.Elasticity– Spell it out in words, a % change in this leads to a % change in…Standard deviations- Useful if you know, pointless if you don’t. Convert to percentages always, and always say from what level the change is happening.Statistical significance– Focus on effect sizesWedge– Difference between x and y

If a reader is thinking about what a word means, they are not thinking about what your research means.

We also do not allow regression tables in our articles. If you have important results, always spell them out. And if you have nice graphs or visualisations in your papers, make sure to add them, and explain what they show (in the text itself, not as extended notes in small font under the image).

And finally, please no puns in titles. For a better title, first think about who your ideal audience is. In a perfect world, who exactly would you want to read your paper? Then try to imagine the types of questions they would ask, and therefore what they might search on google, and voila, you have something approaching a title. In fact, AI can help out with this very problem…

Using generative AI to help summarise an economics paper

This blog post may well become obsolete in a couple of months after the next jump in generative AI’s abilities. Whilst tools like ChatGPT and Claude can’t yet write a perfect summary of an economics paper, they are incredibly useful tools that are particularly suited to summarising the material you feed them. We recently hosted an event with Anton Korinek, who has closely monitored the different use-cases of AI for researchers.

He emphasised that one of the best current uses for generative AI is writing. Some relevant applications include:

- Synthesising text.

- Evaluating text.

- Editing text (for mistakes, style, clarity, simplicity, spelling, grammar, formatting references etc.).

- Generating titles, headlines, teasers and subheadings.

- Generating tweets / promotional materials.

I would highly recommend checking out the event page for more details on using generative AI for economic research.

Other advice on writing for a policy audience

Regularly reading summaries of other research, particularly outside your typical area of work, does wonders for your own writing. Subscribe to our newsletter and you can choose from five articles to read every week.

David Evans has written brilliantly on :

- How to Write the Introduction of Your Development Economics Paper

- Write Your Economics Papers More Clearly. It Pays Off in Influence.

- How To Write the Abstract of Your Development Economics Paper

This two-pager by UCL Public Policy also has lots of useful information on “Writing high-level summaries of your research”.

And finally, we used to recommend checking out the Communicating Economics website, although it now appears as though their website is offline. Their YouTube Channel is still live with videos which provide useful tools, tips and resources for communicating economics with a wider audience.