Closing the gender gap in entrepreneurship is not just a social equity issue—it is a powerful lever for economic growth. Evidence from India shows that women hire more women, and so efforts to boost female entrepreneurship will increase female labour force participation and growth.

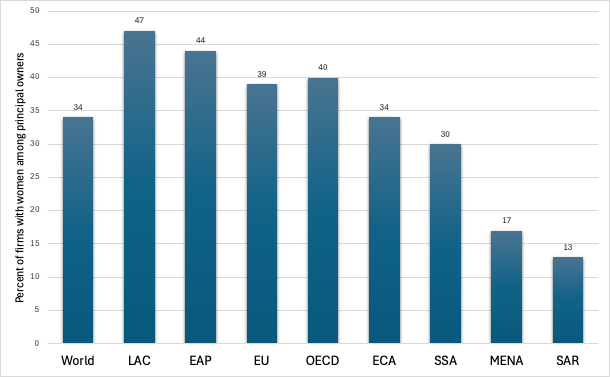

Women across developing countries face significant barriers to participating in the labour force and starting their own businesses. These barriers are especially pronounced in South Asia, where low female labour force participation has persisted for decades despite significant economic growth. The lack of business ownership by women is also striking. Only a third of businesses globally have at least one woman among its principal owners. This ranges from around 45% in Latin America and East- and South-East Asia to only 15% in MENA and South Asia (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of Female-Owned Firms Across Regions

Notes: LAC = Latin America and Caribbean; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; EU = European Union; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; MENA = Middle-East and Northern Africa; SAR = South Asia Region. Data Source: World Bank Gender Data Portal, 2023.

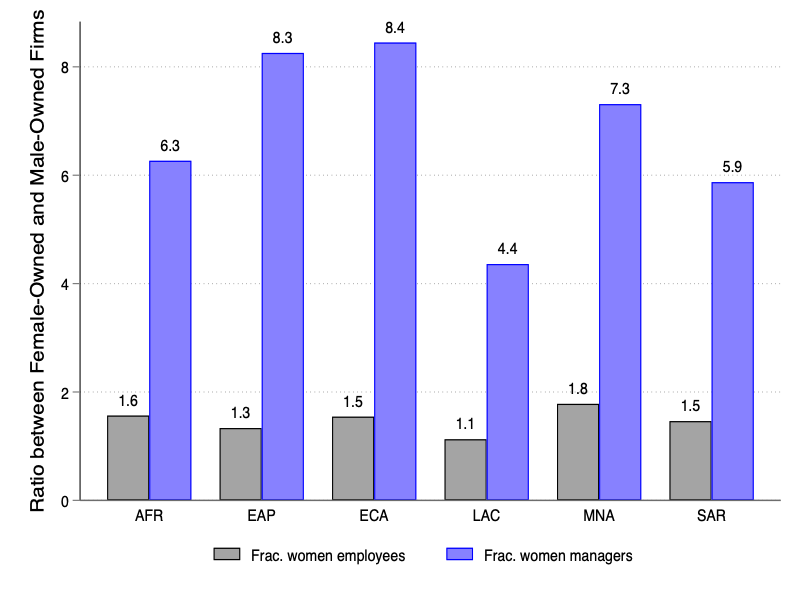

Figure 2 shows that employment patterns differ by owner gender. The figure displays the likelihood that a woman is employed as a worker (gray bar) or manager (blue bar) in a female-owned, relative to a male-owned, firm. A ratio of 1 implies gender parity in the likelihood that a woman is employed as a worker/manager. As is evident from Figure 2, women-owned businesses are 1.5 times more likely to employ women as workers, and around 6-8 times more likely to have another woman as a manager. These patterns suggest that female entrepreneurship may have important implications for women’s employment patterns. Our recent paper (Chiplunkar and Goldberg 2024) sheds new light on how addressing challenges to female entrepreneurship can not only improve gender equality but also spur significant gains in economic productivity and welfare.

Figure 2: Ratio of Female Workers and Managers in Female- and Male-Owned Firms

Notes: The above figure shows the ratio of the fraction of women employees (gray bars) and women managers (blue bars) in female-owned and male-owned firms. LAC = Latin America and Caribbean; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; EU = European Union; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; MENA = Middle-East and Northern Africa; SAR = South Asia Region. Data Source: World Bank Enterprise Surveys, 2006-2018.

Women entrepreneurs in India

Our study focuses on India, where both female entrepreneurship and female labour force participation remain abysmally low, despite decades of rapid economic growth. A rich literature has sought to identify constraints faced by female entrepreneurs using randomised experiments (Quinn and Woodruff 2019, Jayachandran 2021). Our approach differs from this literature in that we develop a unified framework that accounts for multiple gender-related distortions, which we quantify using data from the census of establishments in India. The framework incorporates key features of developing economies, such as the presence of self-employed, owner-operated firms, as well as firms that operate in the informal sector. A key advantage of our approach is that it allows us to analyse how various constraints interact with each other in equilibrium. Among other things, it helps us understand why relaxing one constraint at a time may not be particularly effective when other constraints are binding.

Three key insights on female entrepreneurship in India

Our analysis produces three key insights. First, we generate the well-known finding that women in India face substantial barriers to entering the workforce. However, we find that conditional on working, women do not face significant additional costs (relative to men) in starting businesses. Rather, they are constrained in expanding and formalising their businesses, which limits their growth and scale. In other words, the main barriers are on the intensive, rather than the extensive, margin of entrepreneurship.

Second, consistent with the global patterns described above, we find that women-owned firms have a comparative advantage in the employment of female workers: women work for other women. This relationship is robust to accounting for gender differences in the industries, sectors, and regions where firms are likely to operate, as well as to family-owned and operated businesses. It creates a powerful link between promoting female entrepreneurship and increasing female labour force participation—policies that boost one could significantly increase the other. This is particularly important in a country like India, where female labour force participation remains stubbornly low despite broader economic reforms.

Third, our analysis suggests the presence of low-productivity male entrepreneurs, who operate in the economy only because they are sheltered from competition from more productive female-owned firms facing higher entry and operation barriers. Removing these barriers allows the marginal, higher-productivity female entrepreneur to enter, thus reducing the misallocation of talent and resources in the economy. This more efficient reallocation results in substantial gains in aggregate productivity and welfare (as measured by real income). This positive selection mechanism is consistent with the patterns documented by Ashraf et al. (2024) in the context of the employment patterns in a large multinational.

The economic payoff of eliminating barriers to female entrepreneurs

To understand the broader impact of removing barriers to female entrepreneurship, we conduct a series of counterfactual simulations. These simulations allow us to estimate the economic gains from reducing or eliminating the excess costs faced by women in starting and growing businesses. The results suggest that removing all barriers to female entrepreneurship would lead to a doubling of female-owned firms in India. This would not only boost female labour force participation but also generate substantial productivity and welfare gains for the entire economy. These gains stem from several sources: higher female labour force participation, higher real wages for women, and a reallocation of resources from low-productivity male-owned firms to higher-productivity female-owned firms.

Importantly, these gains come from addressing both supply-side and demand-side constraints. Removing barriers to female labour force participation alone, without addressing the demand for female workers, could lead to a glut of female labour that depresses wages. But when demand-side constraints—such as the higher costs women face in expanding their businesses—are addressed alongside labour force participation barriers, the overall effect is positive: more women in the labour force, higher wages, and greater productivity. This finding underscores the importance of comprehensive, well-targeted policy interventions that address both the demand and supply sides of the labour market.

Policy implications: Where to focus policy to boost female entrepreneurship

Although our analysis is not geared towards evaluating or recommending specific policy interventions, it offers some general lessons for policy makers:

1. Boost female labour force participation through entrepreneurship: Encouraging more women to start businesses has a multiplier effect. Female entrepreneurs tend to hire more women, so promoting female entrepreneurship indirectly boosts female labour force participation even when it does not target the latter directly and does so without depressing real wages.

2. Prioritise the growth of female-owned businesses as opposed to entry: Policies aimed at reducing the operational costs that female entrepreneurs face could unlock significant economic gains. They would enable these businesses to expand, hire more workers, and compete more effectively with other male-owned firms.

3. Address both labour supply and labour demand: Policies that target only female labour supply—for instance, by encouraging women to join the labour force—are unlikely to succeed without measures that also boost the demand for female workers. This means that interventions focusing on inducing women to enter the workforce, should also ensure that there are businesses ready and willing to hire them.

Conclusion: Promoting female entrepreneurship as part of a development strategy

Our research shows that closing the gender gap in entrepreneurship is not just a social equity issue—it is a powerful lever for economic growth. Eliminating the barriers that women face in operating and expanding businesses could increase productivity and improve real incomes for everyone in the economy. As countries across the developing world seek to recover from economic shocks and accelerate long-term growth, promoting female entrepreneurship offers a promising path forward.

References

Ashraf, N, O Bandiera, V Minni, and V Quintas-Martinez (2024), “Gender gaps across the spectrum of development: Local talent and firm productivity,” Working Paper, June 2024.

Chiplunkar, G, and P Goldberg (2024), “Aggregate implications of female entrepreneurship,” Econometrica, 92(6), November 2024.

Jayachandran, S (2021), “Microentrepreneurship in developing countries,” in Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics, pp. 1–31.

Quinn, S, and C Woodruff (2019), “Experiments and entrepreneurship in developing countries,” Annual Review of Economics, 11: 225–248.