A hygiene- and menstruation-focused intervention in Madagascan schools boosted learning, while also reducing stress and improving the psychosocial climate of schools.

Human capital – the skills and health people need to thrive in adult life - can be strongly affected by psychosocial factors. One important psychosocial barrier to girls’ human capital is the social stigma surrounding menstruation. Menstrual stigma is widespread around the world, with one study estimating that one in three women across the world who menstruate risk shame and harassment (WaterAid 2013). And it could damage human capital, for example by inhibiting the flow of information about best practices regarding menstrual hygiene or by inhibiting concentration at school by making girls feel stressed when menstruating.

More broadly, interventions in school – even those targeted on specific behaviours like pedagogy or hygiene – might have important impacts on other aspects of the school psychosocial environment that can have knock-on effects on human capital. For example, hygiene programmes might create a collaborative environment that reduces students’ stress, train teachers in a way that motivates them or increase female empowerment by encouraging active participation in a programme.

Understanding these issues will be crucial in successfully addressing the learning crisis in developing countries, especially since the majority of previous studies evaluating hygiene and menstrual hygiene in schools have tended to focus on attendance instead of learning (Chirgwin et al. 2021), and have placed less emphasis on the psychosocial channels through which learning could be affected.

An intervention to improve hygiene and reduce menstrual stigma

To evaluate how such mechanisms could affect human capital for girls in deprived regions, we conducted a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate a programme run by the NGO CARE. The RCT measured the impact of a set of interventions designed to reduce menstrual stigma and to target a combination of possible hard and soft constraints to hygiene and menstrual management. The programme was evaluated in 140 schools in rural areas of the Amoron’i Mania department of Madagascar and included two components: the base programme and the Young Girl Leader component.

The base programme was a bundle of interventions designed to improve hygiene and reduce stigma in schools, including (i) constructing latrines and handwashing basins at schools, (ii) distributing free menstrual pads for girls and (iii) teacher sensitisation (i.e. raising awareness, increasing understanding, and promoting a shift in attitudes) on a hygiene curriculum, including encouraging them to deliver five-minute sessions on these topics to pupils.

In some schools, this bundle was also combined with a “Young Girl Leaders” intervention. This involved identifying three to four girls in each school who were willing to speak openly and positively about hygiene and menstruation, nominating them as young girl leaders, and training and coaching them to successfully spread effective hygiene behaviours and reduce stigma among their peers. The idea was that these girls would change norms by acting as prominent examples of people within their social network who exhibit good behaviours and who break down the taboo around menstruation.

How does the intervention in Madagascan schools affect human capital?

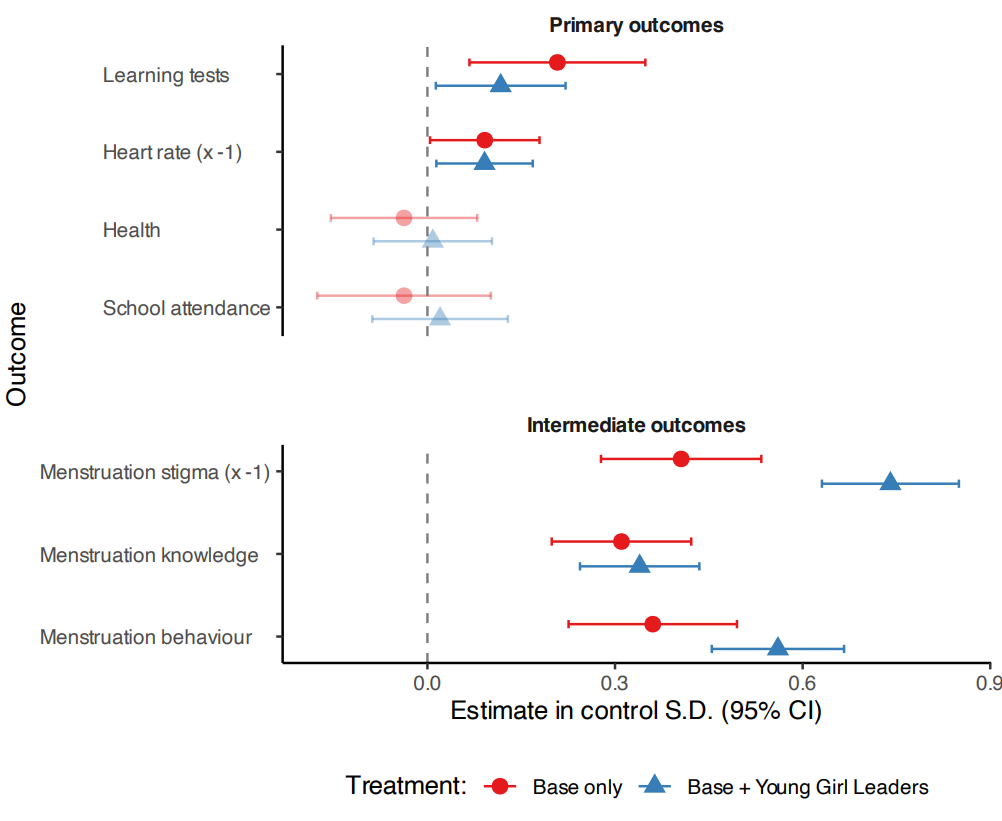

We find that the base programme of hygiene interventions significantly boosts girls’ learning. A set of standardised tests (involving maths, literacy, and cognitive measures) improve by approximately 0.15 standard deviations in treatment schools, an effect that is comparable to highly effective programmes that specifically focus on learning in low- and middle-income countries (Muralidharan 2017). This improvement is also reflected in higher official marks in treatment schools and a 15% increase in the probability of advancing to the next grade without repeating or dropping out.

Interestingly, these learning benefits are not driven by increases in school attendance or enrolment, and we do not find measurable impacts on self-reported health. Instead, the evidence points to the role of improvements in the psychosocial environment at school. We find lower levels of stress among girls, using an objective biomarker: girls’ heart rates measured using wristbands during the endline survey are 2.2 bpm lower. Girls are less exposed to severe bullying, and report having more friends and social connections at school. These changes are important in their own right, indicating improvements in welfare. They could also underlie the learning effects if girls are more able to concentrate when they are less stressed, or if peers learn from each other more when they have stronger social connections.

Figure 1: Effect of interventions on human capital and intermediate outcomes

Young Girl Leaders: Promoting behaviour change and reducing menstrual stigma

Young girl leaders generated important additional changes in hygiene behaviour and stigma. While the base programme led to substantial improvements in girls’ knowledge of hygiene, regardless of whether the young girl leaders were included, the programme generated faster and significantly more improvement in hygiene behaviour when young girl leaders were included.

Young girl leaders also generated significant additional reductions in menstrual stigma, which we evaluated using several survey measures, including measures of attitudes towards menstruation, beliefs about others’ attitudes, and willingness to speak about the topic. Results from interactive exercises, in which girls were asked to explain a topic in front of their class, indicate that the change in reported stigma is also more likely to translate to changes in behaviour when young girl leaders are present in schools.

Together, these results suggest that young girl leaders played an important role in embedding and promoting correct hygienic behaviours in their social network, while also addressing the harmful stigmatising norms around menstruation.

The young girl leaders also played a role in mitigating an important unintended consequence of the programme. In Base Only schools, early pregnancies went up (from 2% to 3.6% of girls), possibly linked to the increased social interactions between boys and girls. But when young girl leaders were present there was no such unintended effect, which may be because she acted as a knowledgeable point of contact for conversations about menstruation and sexuality.

Targeted interventions in schools can tackle social taboos

The study shows that programmes focused on hygiene and menstrual hygiene can lead to improvements in learning and reductions in anxiety in schools in low-income settings, a result that may be driven by changes in social dynamics at schools. Both qualitative and quantitative evidence suggest that other economic constraints are overriding constraints to attendance in this low-income, rural context: for example, the main reason for school dropout is having to work or not being able to pay school fees. Even in such a context, however, an intervention targeting hygiene, menstrual hygiene and stigma has a substantial impact on learning. This implies that policies should therefore seek to leverage these social dynamics, crowding in the effort and motivation, and increasing between-peer solidarity as part of programmes focused on health.

The results also demonstrate that targeted interventions in schools can tackle social taboos. The effects on menstruation-related behaviour and stigma were larger (and started earlier) in schools with young girl leaders - suggesting that this component was effective at tackling this harmful norm. Broadly, this supports the idea that identifying and training “positive deviants” – people in a social network already willing to act in defiance of a harmful norm – may be an effective way of addressing harmful practices or norms in other contexts, such as female genital mutilation, or anti-minority discrimination.

References

Chirgwin, H, S Cairncross, D Zehra, and H Sharma Waddington (2021), “Interventions promoting uptake of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) technologies in low- and middle-income countries: An evidence and gap map of effectiveness studies,” Campbell Systematic Reviews, 17(4): e1194. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1194.

Muralidharan, K (2017), “Field experiments in education in developing countries,” in Handbook of Field Experiments, ed. by A Banerjee and E Duflo, pp. 323–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.hefe.2016.09.004.

WaterAid (2013), “We can’t wait: A report on sanitation and hygiene for women and girls,” WaterAid International. Available at: http://www.zaragoza.es/contenidos/medioambiente/onu/1325-eng_We_cant_wait_sanitation_and_hygiene_for_women_and%20girls.pdf.