A little information goes a long way towards shifting clientelist electoral systems from vote-buying to policy-based competition

Although handwringing and bewilderment followed recent elections in established democracies, voters in many developing countries might prefer such elections to the ones they regularly experience. Despite increasing polarisation, the withering of old parties and the emergence of new, and the manipulation of social media, voters in France, Germany, Italy and the US still identified and voted for the parties that best captured their policy preferences. Voters in many developing countries do not have these options. Instead, their vote depends on which candidates offer them the most goods, services, or cash in exchange for their support. Voters have little reason to pay attention to campaign promises and politicians little reason to make them. Clientelist elections threaten the very self-governing principles a democracy is designed to uphold: they leave politicians unaccountable for policy failure and rent-seeking (Bidner and Francois 2015, Keefer and Vlaicu 2017). All of which raises the question, can countries shift from gift- and favour-based to policy-based elections?

Ilocos - the Philippines

Recent evidence from the Ilocos region of the Philippines suggests that they can and that the door-to-door distribution of a surprisingly simple flyer may be enough to promote this shift. Clientelist politics are dominant in the Philippines (Hicken et al. 2015). Voters accept vote-buying as a fact of life and up to 40% of voters surveyed in some areas report that they received between $20 and $50 for their votes, far exceeding daily household income for most of them. Patronage ties to politicians are also pervasive: almost 20% of individuals report that they know the mayor personally, another 41% report an indirect tie to the mayor through one intermediary. At the same time, voters are substantially uninformed about the policies that politicians control.

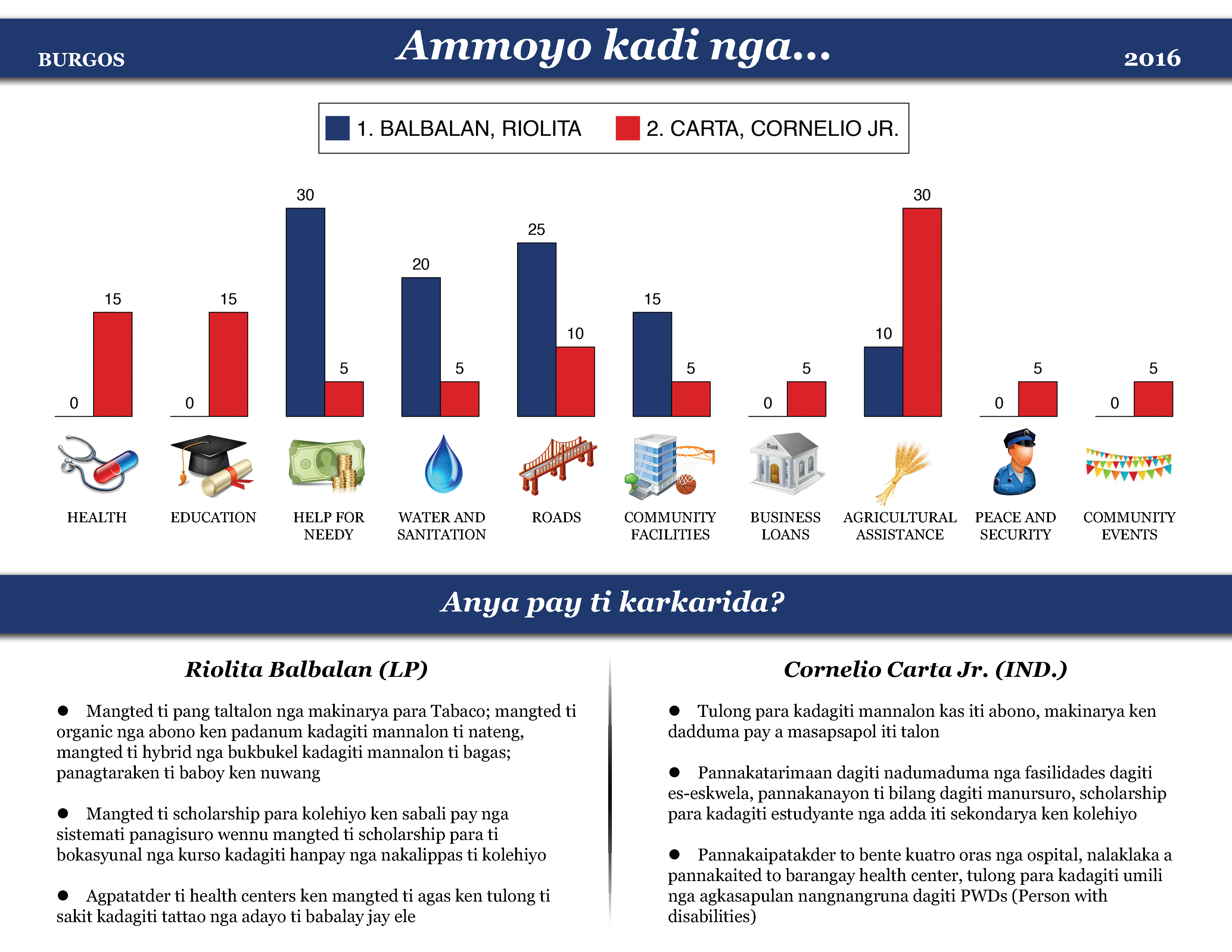

Lack of information undermines accountability in general (Pande 2011); lack of policy information in particular inhibits the emergence of policy-based electoral competition. Hence, over two consecutive mayoral elections in 2013 and 2016, households in more than 150 villages located in seven Ilocos municipalities received flyers informing them about a key municipal public policy and candidate stances on that policy (the flyer for one of the candidates is shown below). We find that by the time of the 2016 election, after the flyers had been distributed for only the second time, politicians and voters acted as if policy mattered (Cruz et al. 2018). Their behaviour more strongly resembled that of Italian municipal elections documented by Kendall et al. (2015) than it had in the elections three years earlier.

What was behind this shift?

One essential ingredient was that the flyers matched information about policy to the officials responsible for the policy. Mayors exercise broad budgetary discretion and control over municipal spending priorities. Indeed, despite the existence of municipal councils, mayors are often characterised as ‘budget dictators’ who are not subject to any meaningful institutional checks and balances. As a result, if voters know the areas of municipal spending responsibility and candidate promises regarding municipal spending, they can reasonably attribute policy outcomes to mayoral (in)action. Voter ignorance about policies and candidate promises therefore short-circuits accountability.

Credible information

Another was that the information was credible. Researchers worked with a local and well-regarded NGO to prepare the flyers with information about candidate promises that would affect the way they vote. The NGO distributed the flyer door-to-door and explained it to voters.

Information that matters

A third key ingredient was that the information concerned programmes that mattered to citizens. Philippine municipalities are responsible for local infrastructure projects, health and nutrition initiatives, and other services. These are largely financed by the federal government through a programme of fixed transfers that constitute 85% of municipal spending. Though municipalities should allocate 20% of the transfers to development projects, many do not.

The authors interviewed mayoral candidates prior to both the 2013 and 2016 elections. Mayors indicated how they would allocate their local government expenditure across 10 categories of public goods and public services. A few days before the elections, voters in randomly-selected villages received information about mayoral candidates’ promises regarding all candidate allocations. In addition, in the flyers distributed prior to the 2016 elections, some voters also received information about promises made prior to the 2013 elections. The flyers therefore told voters about an important public programme that they did not know about before (certainly in 2013), the promises that candidates made, and, in 2016, the promises they made in 2013.

Politicians making policy promises

The first round of flyer distribution constituted the first time that voters had been systematically exposed to information either about local public spending or about candidate promises regarding allocations. It seems to have constituted a sufficient shock to persuade politicians to make policy promises they intended to keep: the number of projects financed by incumbent mayors during the 2013–2016 term increased drastically in the municipalities in which the experiment was implemented. Consistent with the theoretical predictions in Aragonés,et al. (2007), in response to the shock incumbents put more effort into providing public goods, proposed budgetary allocations became more salient, and voters and incumbents had reason to believe that voters would punish incumbents who did not fulfil their promises For example, in 2013, households that received the flyer were more likely to say that municipal spending would influence their voting decision (Cruz et al. 2018).

Voter behaviour

By the time that flyers were once again distributed in 2016, the electoral equilibrium had shifted to one in which information about past and future policy promises could have significant effects on voter behaviour. In fact, after the second round, just prior to the 2016 mayoral election, voters who received information about candidate promises were more certain of their beliefs about candidates’ announced policy platforms and their beliefs were more accurate.

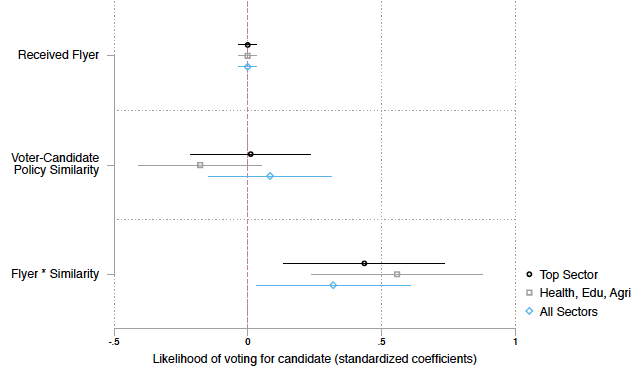

Most importantly, as the figure below shows, in 2016 informed voters were more likely to have supported the candidate whose policies were closer to their own preferences. In short, in 2016, candidates knew that voters were informed about policy and cared about it, voters knew the policies that candidates proposed to implement, and both acted as if policy mattered.

Figure 1 Flyers with campaign promises for the 2016 election led voters to prefer candidates with similar policy preferences

Voters also used the flyer information to make retrospective judgments about politician performance. Those who received information about both current (2016) and past (2013) promises could compare the campaign promises with the actions of incumbent mayors. Compared to other voters, they were more likely to vote for incumbents who fulfilled past promises. They also perceived these incumbents as more honest and competent.

Putting the findings in perspective

The intervention did not turn Ilocos into Switzerland and clientelist relationships between politicians and voters still played a tangible role. Vote-buying was significant even in areas where voters had received flyers. Moreover, voters with personal ties to one of the candidates exhibited a significantly weaker response to information about candidates’ promises. This stands to reason: these voters stood to lose the most by switching to policy-based voting.

At the same time, mayoral candidates in the Philippines are astute campaigners. They understand their constituencies and allocate campaign resources thoughtfully. Why, then, did a third party have to implement this relatively cheap – and electorally effective – flyer campaign? The answer lies precisely with the acute calculations that mayors make regarding campaign strategy: vote-buying is simply more cost-effective. Buying the votes of a household costs more than giving the household informative flyers. However, flyers affect the votes of only a subset of voters, those whose preferences are aligned with the candidate’s promises, and even then are one factor among others that influence voter behaviour. Vote-buying, in contrast, is highly predictive of electoral support. We calculate that flyers returned 16 votes per $500, assuming a candidate could target voters most closely aligned with his or her promises. In comparison, $500 spent on vote-buying returned 40 votes.

A path away from clientelist elections

Despite the advantages of vote-buying relative to policy information campaigns, there is still a path towards elections that give greater weight to policies and programmes. On the one hand, non-governmental or media organisations could provide this type of policy information even if candidates have weak incentives to do so. On the other hand, the more that politicians are compelled to deliver on their policy promises, the less flexibility and resources they have with which to buy votes. Other measures can also make policy-based competition more attractive to politicians relative to vote-buying, but these depend on the politicians themselves. For example, politicians could adopt and enforce measures that criminalise vote-buying, or finance more administrative measures that make vote-buying less efficacious, such as procedural changes to improve voter privacy when casting ballots, and additional safeguards to ensure ballot secrecy.

The Philippines is only one of many countries struggling with the dominance of clientelist politics. But the lessons learned from altering candidates’ incentives and improving voter information could be applied across the world. They could help to provide a pathway for more developing countries to shift to a policy-based political system.

References

Aragonés, E, T Palfrey and A Postlewaite (2007), “Political reputations and campaign promises”, Journal of the European Economic Association 5(4): 846-884.

Binder, C and P Francois (2013), “The Emergence of Political Accountability”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128: 1397-1448.

Cruz, C, P Keefer and J Labonne (2018), “Buying informed voters: New effects of information on voters and candidates”, April.

Cruz, C, P Keefer and J Labonne and Francesco Trebbi (2018). “Making Policies Matter: Voter Responses to Campaign Promises”, NBER Working Paper No. 24785.

Hicken, A, S Leider, N Ravanilla and D Yang (2015), “Measuring vote-selling: Field evidence from the Philippines”, American Economic Review P & P 105(5): 352-56.

Keefer, P and R Vlaicu (2017), “Vote-buying and campaign promises”, Journal of Comparative Economics 45(4): 773-792.

Kendall, C, T Nannicini and F Trebbi (2015), “How do voters respond to information? Evidence from a randomised campaign”, American Economic Review 105(1): 322-53.

Pande, R (2011), “Can informed voters enforce better governance? Experiments in low-income democracies”, Annual Review of Economics 3: 215-237.