A study finds that promoting upstream sectors to counter resource misallocation raises aggregate efficiency

Many developing countries adopt policies that promote selected economic sectors. Japan employed this approach from the 1950s to the 1970s, South Korea and Taiwan followed suit from the 1960s to the 1980s, and China does so today. When does such ‘industrial policy’ make sense? This is an old and contentious question (Hirschman 1958, Krueger 1990, Wade 1990, Williamson 1990, Amsden 1992, Rodrik 2006, Lane 2017).

In a recent paper (Liu 2018), I provide a formal analysis of the economic rationale behind industrial policies. The starting point is that sectors supply inputs to each other – forming a production network – and suffer from some form of market imperfection, such as poor access to credit markets. Such imperfections raise effective input prices and production costs, thereby generating misallocation of resources across sectors and creating room for welfare-improving policy interventions.

Should the government help sectors with the most market imperfections? Or the largest sectors with the most output? The answer is neither. Instead, the key to effective industrial policy lies in the network structure: The government should promote sectors that are more ‘central’ to market imperfections, meaning those that supply a disproportionate fraction of output — directly and indirectly — to other sectors with severe market imperfections.

These central sectors are typically upstream and correspond with the same sectors policymakers seem to view as important targets for intervention. My empirical analysis suggests that industrial policies in modern-day China and historical South Korea might have generated positive aggregate effects.

Why promote upstream sectors?

Policy interventions are only effective if they counteract the misallocation of productive resources. In a production network, distortionary effects of market imperfections compound over input demand linkages. Imperfections cause less-than-optimal levels of input use, thereby depressing the amount of resources used by the input-supplying sectors, who in turn purchase less from their own input suppliers. These effects keep accumulating through intermediate demand. Consequently, certain sectors — those that supply a disproportionate fraction of output to others suffering from market imperfections — become the sinks of all market imperfections and have the most severe under-allocation of resources. The aggregate economy could benefit from policies that redirect resources to these sectors.

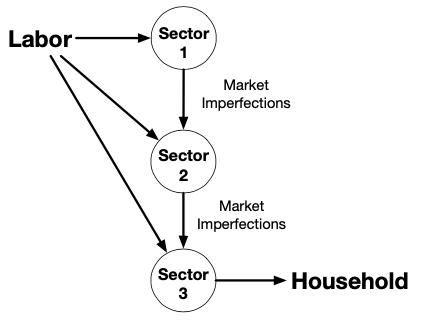

Figure 1 A vertical production chain

Note: The arrrows show the flow of inputs.

This intuition can be understood through an example of a vertical production chain (see Figure 1). All sectors use labour; moreover, sector 1 supplies to 2, sector 2 supplies to 3, and sector 3 supplies to households. Suppose intermediate linkages are subject to credit market frictions, so that sectors 2 and 3 incur additional financial costs when buying goods from sectors 1 and 2.

How do these imperfections affect resource allocation? First, they depress the demand for intermediate inputs, causing sector 1 to under-produce relative to sector 2, and sector 2 to under-produce relative to sector 3. Second, these effects compound backwards, causing upstream sector 1 to be the most under-produced sector. Consequently, policies that subsidise and expand the upstream sector, which is too small, will raise aggregate efficiency.

This example also demonstrates that policy effectiveness depends on the degree of market imperfections, as subsidising upstream can bring large efficiency gains only when resources are severely misallocated by market mechanisms.

Distortion centrality in arbitrary production networks

The structure of real-world production linkages is of course more intricate, but the intuition in Figure 1 generalises to a notion I call ‘distortion centrality’, which applies to arbitrary production networks with market imperfections. Loosely speaking, distortion centrality is a measure of the overall degree of resource misallocation in each sector, after aggregating all effects of market imperfections that compound through production linkages. This measure guides policy interventions because it quantitatively summarises the social value of policy spending in each sector.

Distortion centrality has the following properties:

- Promoting sectors with distortion centrality above one brings aggregate efficiency gains — the higher distortion centrality, the more gains — and promoting sectors with distortion centrality below one generates aggregate efficiency losses.

- Distortion centrality averages to one across all sectors; hence, uniformly promoting all sectors has no aggregate impact.

- Distortion centrality depends on both the distribution of market imperfections in the economy and the network structure, including cross-industry input-output linkages as well as imports and exports. The measure tends to be higher in sectors that supply a disproportionate fraction of output — directly and indirectly — to sectors that suffer the most from market imperfections.

- The measure is substantively different from sectoral size, as measured by output or value-added, and other notions of sectoral importance, such as the degree of within-sector market imperfections.

- In a vertical production chain, more upstream sectors always have higher distortion centrality.

China and South Korea: Generalisations of vertical production chains

In a general network, every sector supplies to many others, and the notion of ‘upstream’ might not be well defined. Identifying sectors with high distortion centrality hence requires knowledge of market imperfections, which are difficult to estimate. Indeed, a leading criticism of industrial policies is that governments have difficulty identifying market imperfections (Pack and Saggi 2006).

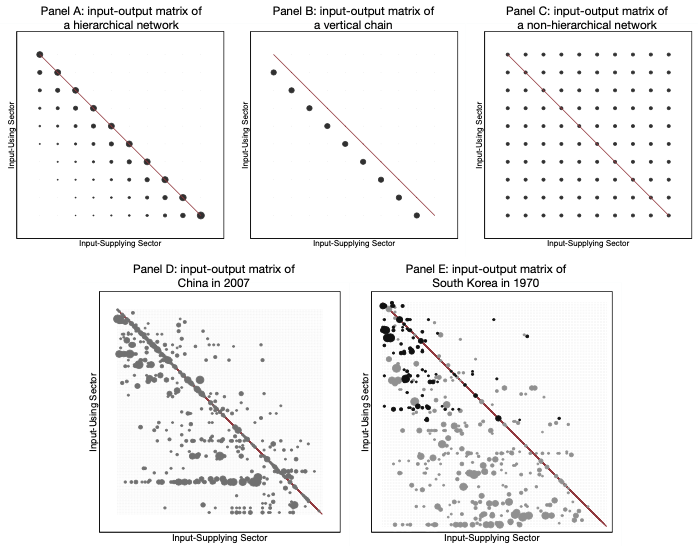

Considering these challenges, is this theory practically useful? I empirically examine the input-output matrices of modern-day China and historical South Korea, two of the most salient economies with active government interventions. I find these networks to be ‘hierarchical’, meaning they are generalisations of vertical production chains: Their sectors can be ranked by a well-defined notion of ‘upstreamness’, so that upstream sectors supply a disproportionate fraction of output to other relatively upstream sectors (see Figure 2).

Hierarchical networks are similar to vertical chains, in the sense that distortion centrality is insensitive to underlying market imperfections and tends to align with sectoral upstreamness. This implies that sectoral distortion centrality in China and South Korea can be computed based on input-output matrices, without having to precisely estimate market imperfections in these economies.

Figure 2 Hierarchical, vertical, non-hierarchical, and real-world input-output matrices

Notes: These figures display five input-output matrices, which visualise the structure of cross-sector production networks. In each matrix, columns represent input-using sectors and rows represent input-supplying sectors. The size of each cell represents the strength of the input-output demand relationship, i.e. cell (i,j) is drawn in proportion to the fraction of sector j’s output that is used by sector i. The diagonal (highlighted in red) captures the fraction of each sector’s output used by the sector itself. Panel A represents a typical hierarchical network. Sectors are arranged in decreasing order of upstreamness; more upstream sectors supply a disproportionate fraction of output to other relatively upstream sectors. Panel B represents a vertical production chain: Sector 1 supplies only to sector 2, which supplies only to 3, etc. Panel C represents a symmetric production network, which is non-hierarchical and does not have a well-defined notion of “upstream”. Panels D and E demonstrate that input-output matrices in China and South Korea bear striking resemblance to the hierarchical network in Panel A. In Panel E, cells are darkened if the input-using sector were promoted by South Korea’s industrial policies during the “Heavy-Chemical Industry” drive in the 1970s. The pattern shows that promoted sectors were all upstream, as they supply strongly to other downstream sectors but use few downstream inputs in return.

Promoting upstream sectors raise aggregate efficiency

I find that the heavy and chemical sectors promoted by South Korea in the 1970s are upstream (as visibly evident from Figure 2E) and have significantly higher distortion centrality than non-targeted sectors, suggesting that government interventions contributed positively to aggregate economic performance.

In modern-day China, non-state-owned firms in sectors with higher distortion centrality have significantly better access to loans, receive more favourable interest rates, and pay lower taxes. These sectors also tend to have more state-owned enterprises, to which the government directly extends credit and policy subsidies.

My quantitative analysis reveals that in China, differential sectoral interest rates, tax incentives, and funds given to state-owned enterprises all generated positive aggregate effects and, taken together, improve aggregate efficiency by 4.8%. Moreover, distortion centrality correlates negatively with sectoral size, suggesting that promoting large sectors would have led to aggregate losses.

Final remarks and caveats

The predominant view in economics research is that industrial policies tend to generate resource misallocations and harm developing economies (for example, see the survey by Rodrik 2006). Yet, my findings show there may be an economic rationale behind certain aspects of South Korean and Chinese industrial policies, and that these policies might have generated positive economic effects. An important caveat is that these findings do not speak to the decision process behind such policies, as my analysis abstracts away from various political economy factors that affect policy choices in these economies (Krueger 1990, Rodrik 2008).

Editors' note: This blog is part of the VoxDev series on industrial organisation.

References

Amsden, A (1992), Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization, Second edition, New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

Hirschman, A O (1958), The Strategy of Economic Development, Third edition, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Krueger, A O (1990), “Government Failures in Development”, Journal of Economic Perspectives.

Lane, N (2017), “Manufacturing Revolutions: Industrial Policy and Networks in South Korea”, Working Paper.

Liu, E (2018), “Industrial Policies in Production Networks”, Working Paper.

Rodrik, D (2006), “Goodbye Washington Consensus, Hello Washington Confusion? A Review of the World Bank’s Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform”, Journal of Economic Literature.

Rodrik, D (2008), “Normalizing Industrial Policy”, Commission on Growth and Development Working Paper No. 3.

Wade R H (1990), Governing the Market: Economic Theory and the Role of Government in East Asian Industrialization, Second edition, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Williamson, J (1990), Latin American Adjustment: How Much Has It Happened?, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Pack, H and Saggi, K (2006). “The Case for Industrial Policy: A Critical Survey”, The World Bank Research Observer.