New studies measure how many people cannot afford a healthy diet, establishing a useful benchmark for understanding global food systems and poverty

Control of infectious diseases has made dietary intake the world’s #1 most important avoidable cause of death and disability, by raising the risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer (Gakidou et al. 2017). To boost longevity now, most of us should eat more vegetables and fruits, nuts and seeds that provide healthier fats than what is in red meat. Many people should also cut back on sugar, salt, refined starches, and processed meats. Changing food systems is also important for the global environment (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2019), to help cut emissions and air pollution, store more carbon in soils and forests, preserve water supplies, stop antibiotic uses that breed superbugs, and take other steps to protect natural resources.

A globally applicable reference diet

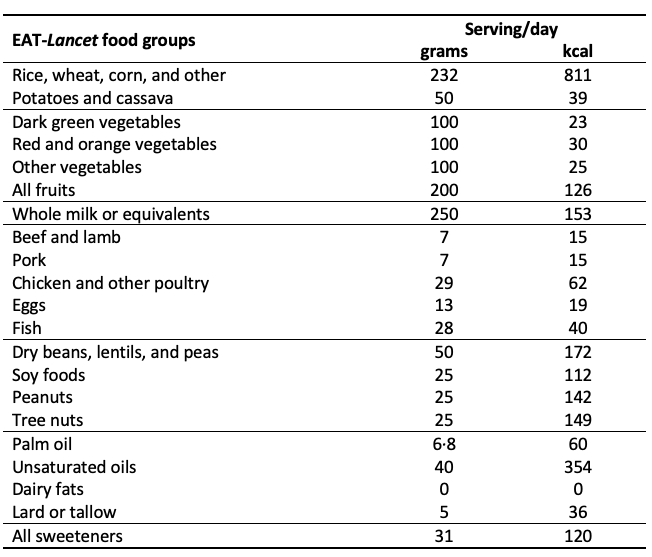

In January 2019, the EAT-Lancet Commission launched a major report (Willett et al. 2019) providing the first globally applicable benchmark ‘reference diet’ towards which all people might converge to limit diet-related disease risks, while preserving the environment and accommodating most dietary traditions. Table 1 shows the Commission’s recommended intake for a typical adult across the major food groups. Like many nutritionally recommended diets, EAT-Lancet proposes eating a diverse range of fresh or lightly processed foods, and limiting one’s intake of red meat, sugar, and fats/oils relative to current diets in high-income countries.

Table 1 Content of the EAT-Lancet reference diet (2,503 kcal)

The EAT-Lancet Commission’s reference diet is intended to be realistic and palatable, including a variety of more attractive (and more expensive) foods than would be needed to meet minimally adequate levels of essential nutrients, or the minimal caloric requirements for day-to-day energy balance. The Commission also deliberately left food prices and diet costs out of their calculations. Many experts – and non-experts – have debated the scientific merits of the EAT-Lancet reference diet (Food Climate Research Network 2019). A key feature for economists is that it provides a benchmark set of foods with which to compare the cost of a similar diet around the world for comparison relative to income and relative to nutrient adequacy or energy balance, in a way that brings much more information about nutrition and health than previous efforts such as Allen (2017).

Using retail prices to measure the cost of diets

In a new study in Lancet Global Health (Hirvonen et al. 2019), we use retail prices from around the world to measure the cost of an EAT-Lancet diet, and what fraction of total spending on all goods and services would be needed just for that grocery basket. A companion working paper (Alemu et al. 2019) provides more detailed results for essential nutrient requirements, from a larger programme funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation with UKAid.

The affordability of healthy diets in each country, using only the least expensive locally available items to meet benchmark levels of each food group or essential nutrients, offers a revealing new approach to studying food systems in low-income countries (Masters et al. 2018). In rich countries, the grocery bill for an EAT-Lancet diet is much less than most people spend on food, so our diet quality and environmental impact depend on food choices, driven by taste and convenience among other factors. The questions we ask in our research on the cost of alternative diets concern the world’s poorest people: in what countries, and for how many people, is the least-cost version of a healthy diet using local foods still unaffordable?

People who cannot afford a reference diet are currently consuming other foods, often close to a subsistence diet that provides only daily energy. For them, improving diet quality must start with higher income from work or a social safety net, as well as lower prices from public investment in agriculture and the food system. For people who cannot afford a recommended diet, nutrition education and behaviour-change campaigns are an exercise in futility.

To measure affordability of EAT-Lancet diets, we calculate the cheapest means of achieving energy balance using reference levels of each food group, in each of 159 countries that had both per capita income estimates and retail prices of standardised food products collected under the International Comparison Programme. We used the price data to cost the cheapest EAT-Lancet diet in each country and then compare these diet costs to various per capita income measures, and the least-cost way of meeting essential nutrient requirements.

Many people cannot afford an EAT-Lancet diet, or even minimal nutrient adequacy

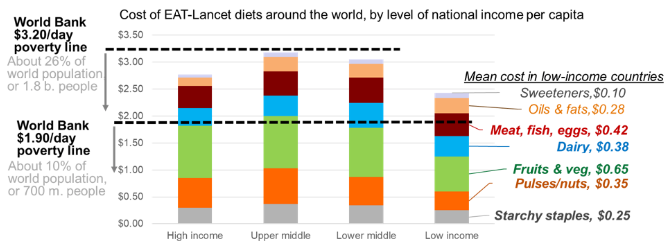

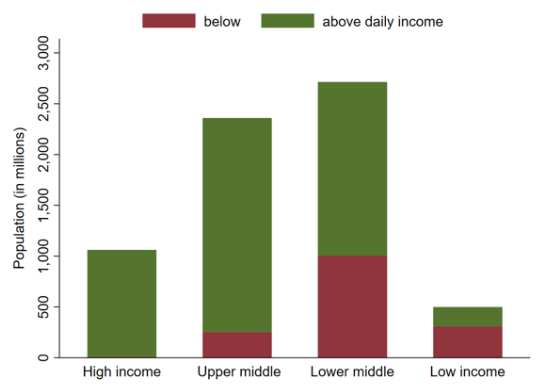

Globally, the median cost of the EAT-Lancet reference diet was $2.89 per day in 2011 international dollars, well above the World Bank’s poverty line of $1.90. This sets the tone for our main finding: many people around the world cannot afford these foods, even if they wanted to buy them (Figure 1). We find that buying the cheapest EAT-Lancet diet would take 90% of daily household income in low-income countries, and that 1.58 billion people around the world could not afford such a diet (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1 The cost of the EAT-Lancet reference diet exceeds the international poverty with fruits & vegetables and animal source foods (meat, fish, eggs and dairy) being the most expensive components

Figure 2 About 1.58 billion people have daily incomes below the cost of the EAT-Lancet reference diet, most of whom are in middle-income countries

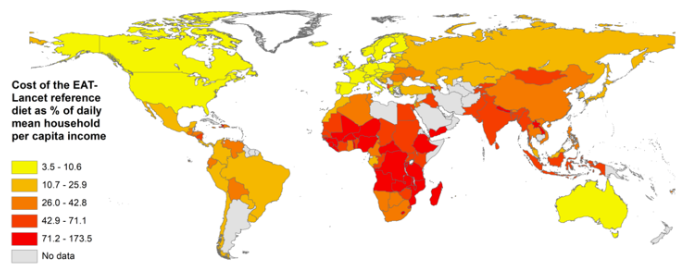

Figure 3 The cost of the EAT-Lancet reference diet is particularly unaffordable in Africa and South Asia

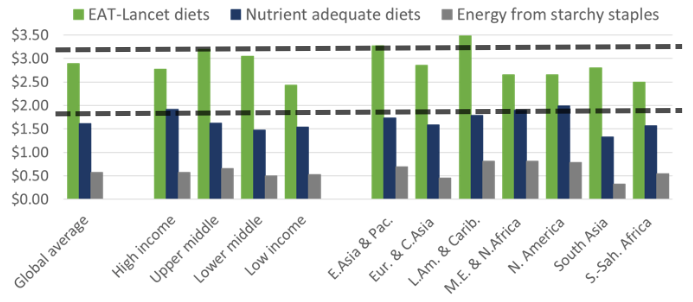

As shown in Figure 3, the costs of the EAT-Lancet reference diet are well above the minimum cost of obtaining adequate levels of essential nutrients, which in turn are well above the cost of daily energy. In a related working paper (Alemu et al. 2019), we study the cost of meeting nutrient requirements in more detail, and in related work on dietary recommendations within individual countries such as Myanmar (Mahrt et al. 2019). We find the same result: the high cost of nutritious foods makes healthy diets out of reach for many poor people, as an overall healthy diet would cost more than they now spend on all goods and services combined.

Figure 4 The cost of an EAT-Lancet diet is much higher than the cost of nutrient adequacy or daily energy requirements

Note: Horizontal lines show World Bank poverty lines at $1.90 and $3.20.

Policy implications: What can be done to put healthier diets within reach?

- Raising the real incomes of the poor is a necessary condition for improving their diets. Other steps must follow, but without higher income or safety-net transfers, the poor are unable to make better food choices. The estimates produced in our study can help governments and philanthropic donors target their efforts at poverty reduction, including efficient and effective designs for cash and food transfers (Ahmed et al. 2019).

- Lowering food prices in low-income regions plays a major role in both poverty reduction and dietary improvement. Nutrition-smart food policies start with public investments to improve availability and reduce prices for healthier items. The cost of an EAT-Lancet diet is driven mainly by the most expensive food groups, such as fruits, vegetables, and healthy animal-sourced foods like milk, eggs, and fish which our related work shows are particularly expensive in low-income countries (Headey and Alderman 2019). In most of Africa and South Asia, the high cost of nutritious diets stems partly from low productivity on the farm, but also from poor infrastructure and inefficiencies off the farm in storage, transport, and processing.

- We know that having lower-cost, healthier ingredients available in local markets is only the start of a better diet. As diverse options become more affordable – including unhealthy items like sugary drinks and salty snacks – taste and convenience become the driving force in food choice. On this front, governments must address nutritional risks the same way we address food safety, auto safety, or drugs and alcohol: more investment in education about risks (especially for school age children and parents), and much stronger regulation of food labelling and marketing so that buyers can really beware.

The EAT-Lancet reference diet provides a valuable benchmark against which to see the obstacles to improvement in what we eat around the world, pointing to specific actions for achieving a healthier and more sustainable global food system. Higher incomes for the poor, lower prices for healthier foods, and limits on harmful items can drive a better food system in every country, for human health and the world as a whole.

References

Ahmed, A, J Hoddinott, S Roy, E Sraboni (2019), “Transfers, nutrition programming, and economic well-being: Experimental evidence from Bangladesh”, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Alemu, R, Y Bai, S Block, D Headey and W Masters (2019), “Cost and affordability of nutritious diets at retail prices: Evidence from 744 foods in 159 countries”, Tufts University Department of Economics Working Paper.

Allen, R (2017), “Absolute poverty: When necessity displaces desire”, American Economic Review 107(12): 3690-3721.

Food Climate Research Network (2019), “Reactions to the EAT-Lancet Commission”.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2019). Climate change and land. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Gakidou, E, A Afshin, A. et al. (2017), “Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: Asystematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016”, The Lancet 390(10100): 1345-1422.

Headey, D and H Alderman (2019), “The relative caloric prices of healthy and unhealthy foods differ systematically across income levels and continents”, The Journal of Nutrition 149(11): 2020-2033.

Hirvonen, K, Y Bai, D Headey and W. Masters (2019), "Affordability of the EAT–Lancet reference diet: A global analysis”, Lancet Global Health.

Mahrt, K, D Mather, A Herforth and D Headey (2019), “Household dietary patterns and the cost of a nutritious diet in Myanmar”, IFPRI Discussion Paper 1854. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Res Institute.

Masters, WA, Y Bai, A Herforth, DB Sarpong, F Mishili, J Kinabo, JC Coates (2018), "Measuring the Affordability of Nutritious Diets in Africa: Price Indexes for Diet Diversity and the Cost of Nutrient Adequacy", American Journal of Agricultural Economics 100(5):1285-301.

Willett, W, J Rockstrom, B Loken, M Springmann, T Lang, S Vermeulen, T Garnett, D Tilman, F DeClerk, A Wood, M Jonell, M Clark, L Gordon, J Fanzo, C Hawkes, R Zurayk, J Rivera, W De Vries, L Majele Sibanda, A Afshin, A Chaudhary, M Herrero, R Agustina, F Branca, A Lartey, S Fan, B Crona, E Fox, V Bignet, M Troell, T Lindahl, S Singh, S Cornell, S Reddy, S Narain, S Nishtar, C Murray (2019), “Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems”, The Lancet Commissions 393(10170): 447-492.