Evidence from 25 years of data shows countries form persistent ‘development clusters’ according to their levels of internal peace and state capacity

Over 260 years ago, Adam Smith famously said "Little else is required to carry the state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice, all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things." This recipe for prosperity has two essential ingredients.

The first is peace. Throughout history, wars have been very destructive – even though international wars sometimes precipitate nation building by pulling citizens together. However, civil wars generally inhibit nation building, as rival groups fight to control the state (Blattman and Miguel 2010, Ch et al. 2019, Xu and Yang 2018). Groups can sometimes resolve underlying political conflicts by working together, as when the long Colombian civil war ended in 2016 under the leadership of President Santos. However, other conflicts end only by one group holding onto power by repressing others, as when the brutal Syrian civil war tapered off into the repression pursued by President Assad.

Smith’s second ingredient is an effective state. This is our interpretation of easy taxes and the administration of justice. Besley and Persson (2011a) call these fiscal and legal capacities (of the state). Efficient states use these to support markets and provide various public goods, rather than pandering to special interests. We now refer to the capability to provide public goods like health and education as state’s collective capacity. Together with peace, these three state capacities are key Pillars of Prosperity for effective states.

Neither forging a durable peace, nor building state capacities are accidental. Both require strategic decisions by governments and influential groups, supported by institutions and values (norms). Besley and Persson (2009) argued that cohesive institutions can prevent ruling groups from using the state as a private project for self-enrichment. In some states, legislative and judicial oversight serve as checks and balances, inducing government to pursue the public interest. Such constraints also reduce the motive to capture the state by domestic violence. Norms and values have coevolved with these institutions; in many countries, government would not be able repudiate institutional arrangements without reproach. Thus, building state capacities and maintaining peace have common origins.

These two aspects of nation building are complementary in more than one way. For example, peace and legally protected property rights are both conducive to private investment. Such investments encourage governments to build tax systems that allow economic growth to be channelled into greater collective provision of health and education. All these effects more or less point in the direction of greater prosperity and well-being.

We thus expect to observe development clusters, where strong state capacities, peace and income coexist. Besley and Persson (2011a) proposed a typology of states, based on Smith’s two dimensions. In one dimension, countries are peaceful, repressive, or in civil conflict, based on the analysis developed in Besley and Persson (2011b). In the other dimension, states are either common interest, redistributive, or weak. Common interest states have strong institutional constraints on government. Redistributive states have a single group that has captured the state, operating it as a fiefdom – like the Chinese Communist party, the ruling monarchies in the oil rich Middle East, or dictatorships like Syria. Citizens must then rely on ruler benevolence for building state capacities. While China finds it inconvenient to build the legal capacities that would constrain party power, it does strive to provide good health care and education. Weak states have neither cohesive institutions, nor control by a single group. This entails weak incentives to build state capacities, and civil war (or repression) is an important source of political instability which deters private investment.

Besley and Persson (2011a) developed a crude Pillars of Prosperity Index to reflect Smith’s two drivers – state capacities and peace – and their link to prosperity. Recently, we updated this index with more recent and better data, ten years after our initial effort (see new website with updated materials here). We had previously struggled, for example, to find good measures of taxation comparable across countries – a key empirical issue when studying fiscal capacity (Albers, Jerven and Suesse 2020). But we are now able to use new data from the International Center for Taxation and Development (ICTD). For 67 countries, we have a consistent picture of the past 25 years for our key variables: fiscal, legal, and collective capacities – we also have data for income per capita, and for civil war, repression, and peace (Besley et al. 2021 provide details).

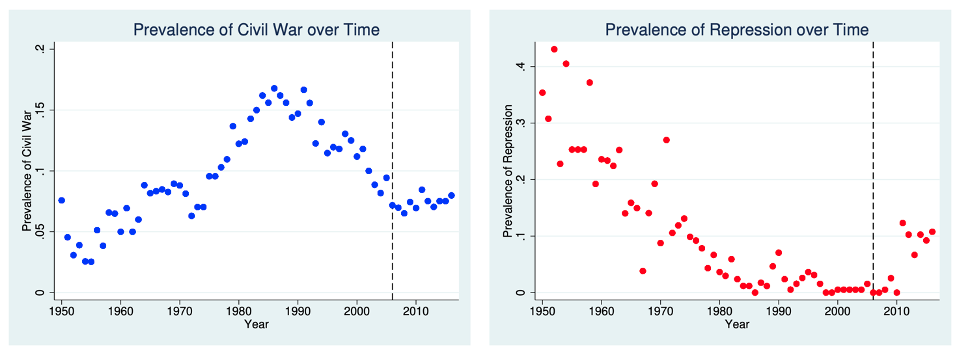

Figure 1 shows how a previous downward trend for both forms of political violence broke in 2006: today, about 10% of nations have either civil war and/or repression (the dashed line marks the last data in Besley and Persson 2011b).

Figure 1

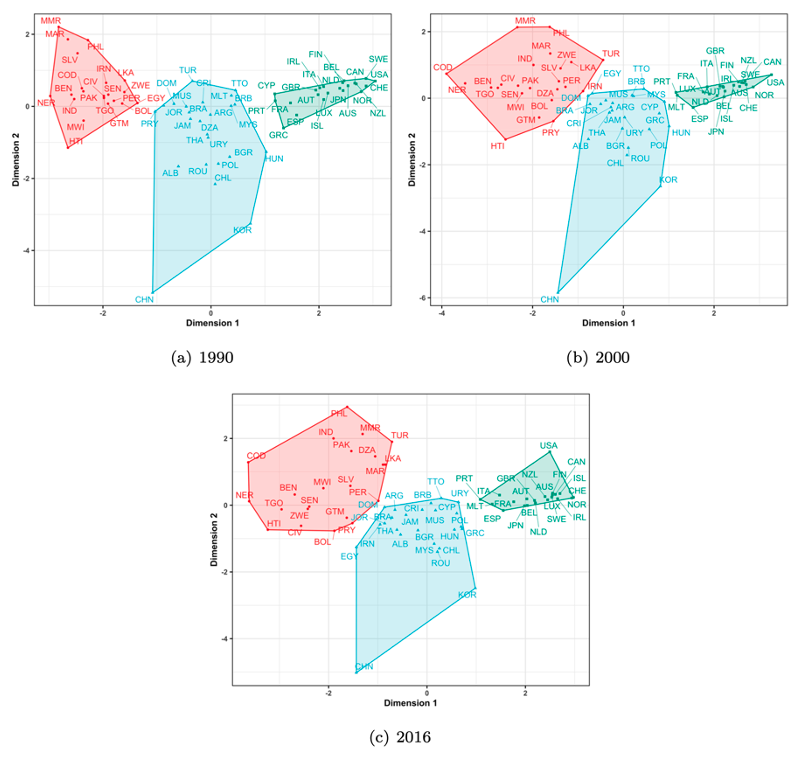

To summarise the overall data patterns, we employ a hierarchical agglomerative clustering (HAC) approach from the data-science literature on machine learning (Husson et al. 2010). To gauge country similarity, this method asks the computer to discern naturally occurring clusters of countries, when fed with the raw variables comprising the Pillars of Prosperity Index. We look at three dates: 1990, 2000, and 2016 and ask whether the algorithm supports our conjecture of development clusters. Next, we explore the stability of these clusters over time. Figure 2 shows that countries do cluster into three groups which are remarkably stable over 25 years. The three groups fit neatly into our typology of common interest, redistributive, and weak states (Besley et al. 2021).

Figure 2

This finding is not surprising, in view of the logic in Besley and Persson (2011a); common causes and complementarities provide a joint platform for building peace, state capacities, and prosperity (Acemoglu et al. 2016). Although institutions do change as emphasised by, for example, Acemoglu and Robinson (2006), strong state capacities as well as durable peace reflect long-term factors. The norms and values that build cohesion are also slow moving. The overall message thus brings good and bad news. On the one hand, it takes time to build a common-interest state when institutions and norms are an important piece of the scaffolding. On the other, once established, they may form a bond that ties institutions and state capacities together.

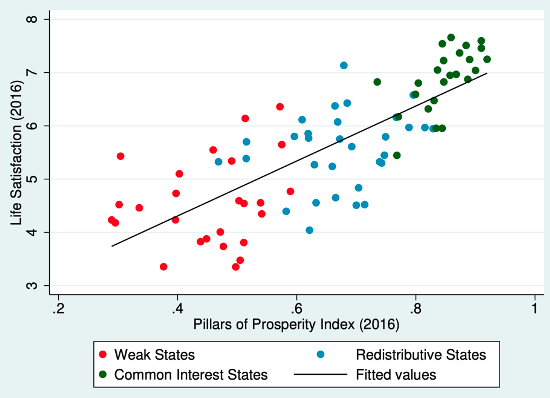

Economists are used to tracking progress via income per capita and, more recently, via subjective well-being as measured in life satisfaction surveys. Figure 3 shows a strong positive correlation between the Pillars of Prosperity Index and life satisfaction from the World Happiness Report for 2016, with a near monotonic ordering of state spaces.

Figure 3

Political economics has also grown accustomed to looking at data on democracy and other political institutions, otherwise studied by political scientists. The latter also look routinely at data on peace and repression (although typically as separate rather than joint outcomes).

Internal peace and security along with state capacities, in Adam Smith’s spirit, are important intermediate inputs into human progress. They deserve to be tracked, alongside more standard measures of societal well-being. However, even when state capacities and the absence of violence correlate well with income and life satisfaction, their benefits run much deeper than what a single, aggregate indicator can capture. Many elements of state and society support people’s ability to lead fulfilling lives such as when legal capacity supports basic freedoms.

A multi-dimensional research programme, along the lines we have sketched, draws on many parts of social science, including economics, history, political science, social psychology, and sociology. The slow movements of peace and state capacity underlines that some countries in the world have found a stable way to achieve them. The failure of almost any country to move across clusters in Figure 2 also suggests that those who work on globally promoting the pillars of prosperity still have a great deal to do.

Editors' note: This column first appeared on VoxEU.

References

Acemoglu, D and J Robinson (2006), Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy, Cambridge University Press.

Acemoglu, D, L Fergusson, J Robinson, D Romero and J F Vargas (2016), “How not to build a state: Evidence from Colombia,” VoxEU.org, 6 October.

Albers, T, M Jerven and M Suesse (2020), “On the development of fiscal capacity: New insights from African data,” VoxEU.org, 22 November.

Besley, T and T Persson (2009), “The Origins of State Capacity: Property Rights, Taxation, and Politics,” American Economic Review, 1218-1244.

Besley, T and T Persson (2011), Pillars of Prosperity: The Political Economics of Development Clusters, Princeton University Press.

Besley, T and T Persson (2011), “The Logic of Political Violence,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1411-1445.

Besley T, C Dann and T Persson (2021), “Pillars of Prosperity: A Ten-Year Update,” CEPR Discussion Paper 16256.

Besley, T, C Dann and T Persson (2021), Pillars of Prosperity, retrieved from STICERD.

Blattman, C and E Miguel (2010), “Civil War,” Journal of Economic Literature, 3-57.

Ch, R, J Shapiro, A Steele and J Vargas (2019), “Death and taxes: Political violence shapes local fiscal institutions and state building,” VoxEU.org, 29 January.

Husson, F, J Josse and J Pages (2010), “Principal component methods - hierarchical clustering - partitional clustering: why would we need to choose for visualizing data?” Applied Mathematics Department, 1-17.

Xu, C L and L Yang (2018), “Stationary bandits, state capacity, and the Malthusian transition: The lasting impact of the Taiping Rebellion” VoxEU.org, 11 November.