Changing economic conditions have differing impacts on women’s marital outcomes and family formation in polygynous vs non-polygynous areas

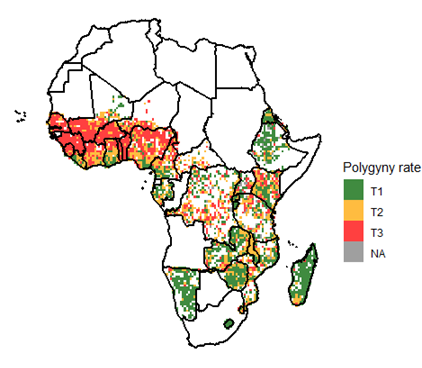

Social norms and culture are crucial for economic development, and the efficacy of policy interventions may depend on the local environments in which they are enacted (Ashraf et al. 2020, Collier 2017, World Bank 2015). Across sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), marriage markets (an important determinant of household welfare) are governed by very diverse and persistent local norms regarding polygyny. This custom that allows men to simultaneously have multiple wives is still widespread in some areas, while others are essentially monogamous, as shown in Figure 1. The variation in local polygyny norms stems from several historic and slow-moving cultural/socio-economic factors (Fenske 2015, Tertilt 2005, Jacoby 1995).

Figure 1: Practice of polygyny across space in Sub-Saharan Africa

Note: Polygyny rate is the average share of women (aged 25 and older) that are in a union with a polygamous male in each 0.5 x 0.5 decimal degree grid cell (roughly 55km x 55km at the equator). It is computed from Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data. The continuous rate is split in terciles. T1 represents grid cells with low polygyny (less than 16%), T2 is for areas with medium polygyny (between 16 and 40%), and T3 is for areas with high polygyny (more than 40%).

Bride price (payment from the groom’s family to the bride’s family at the time of marriage) is also customary in many parts of SSA, thereby making marital outcomes potentially sensitive to changes in aggregate economic conditions. In an influential paper, Corno et al. (2020) show that droughts increase child marriage (which is associated with bad health and socio-economic outcomes for women and their offspring) on average across SSA. However, their analysis assumed that marriage markets are monogamous, so it is still unclear as to how polygynous markets are affected by such economic shocks.

Polygyny, economic shocks, and family formation outcomes

The presence of polygyny changes the structure of the marriage market. It also gives rise to two other key family formation outcomes besides the timing of unions for girls: spousal ranking and husband-wife age gap. Women who enter marriages as second/junior spouses tend to have a low status and bargaining power within their households (Munro et al. 2019, Matz 2016, Reynoso 2019). Husband-wife age gaps are often significant in polygynous areas, which is also associated with low bargaining power (Carmichael 2011, Atkinson and Glass 1985). Understanding the economic drivers of these three key marital outcomes is therefore crucial for policy design and evaluation across the culturally diverse areas of SSA.

In a recent paper (Tapsoba 2022), I study how short-term changes in aggregate economic conditions affect family formation outcomes in the presence of polygyny. Across SSA, polygyny is in fact a sequential process of one-to-one matching, with an average of 10 years between the arrival of the first and the second spouse. In each period, the demand side of the market has two independent components: a demand for first/unique spouses from young bachelors, and a demand for second spouses from older men. A simple supply and demand model shows that the relative sensitivity of these two components to income and bride price changes will determine how aggregate shocks will affect their respective market shares, and hence women’s marital outcomes.

Rainfall and global food price fluctuations as sources of exogenous economic shocks

I construct a measure of local droughts as calendar year rainfall below the 15th percentile of a location’s long-run rainfall distribution. This measure is a good proxy for adverse economic shocks (Corno et al. 2020, Burke et al. 2015). The timing of droughts is random, so different cohorts of children will be exogenously exposed to them, or not, at a given age.

The second source of income variation is due to fluctuations in international crop prices. These fluctuations are exogenous to local economies, given that the entire continent accounts for less than 6% of global production. A price spike can be expected to significantly raise income for agricultural producers and reduce real income for consumers at the same time. Following McGuirk and Burke (2020), I separate these producer and consumer effects within countries using detailed spatial data on where specific crops are grown and consumed.

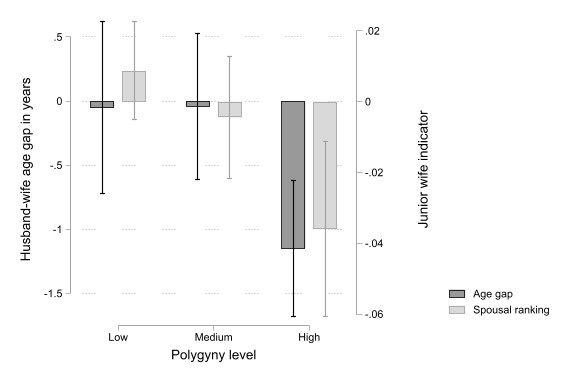

Effect of droughts on husband-wife age gap and spousal ranking

In high polygyny areas, exposure to a drought during the prime age for marriage (age 12-24) decreases the husband-wife age gap by 1.2 years for girls (10% of the average age gap). It also leads to a 3.9 percentage points decrease in the likelihood of marrying as a junior spouse in these areas. In contrast, there is no statistically significant link between rainfall shocks and the husband-wife age gap or the spousal ranking in low and medium polygyny areas (figure 2). Robustness checks also show that this heterogeneity is not driven by other important cultural factors that may be correlated with polygyny norms, such as patrilineality, women’s traditional role in agriculture, or the practice of Islam.

Figure 2: Impact of droughts on husband-wife age gap and spousal ranking

Note: Graph shows the estimated impact of droughts on the husband-wife age gap (left y-axis) and spousal ranking (right y-axis), together with 95% confidence intervals (capped spikes). The estimated coefficients for low and high polygyny areas are statistically different from each other at a 5% significance level for both outcomes.

These results are consistent with the idea that aggregate adverse shocks increase the market shares of young bachelors that are looking for first spouses at the expense of older men that are looking for second spouses. This happens because we are in a setting where polygyny is common even among relatively poor men (not just a select wealthy elite), so the demand for second spouses is more sensitive to income and bride price changes than the demand for first/unique spouses.

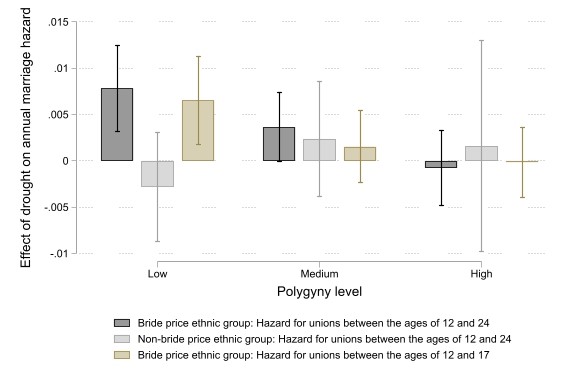

Effect of droughts on the timing of marriage, child marriage, and fertility onset

The paper also shows that droughts increase child marriage in monogamous areas, but this effect diminishes as we move to areas with higher polygyny rates until it vanishes completely. Intuitively, negative shocks increase child marriage in monogamous settings because the supply of child brides is more sensitive to the drop in income and bride price compared to the demand for child brides, as shown in Corno et al. (2020). In the presence of polygyny, the fact that there is a second component (demand for second spouses) that is more sensitive to the income and bride price changes explains why droughts will have a weaker effect.

The estimated impact of droughts on the annual hazard of marriage between ages 12 and 24 goes from 0.64 percentage points for low polygyny areas to 0.38 percentage points in areas with medium polygyny levels. In contrast, there is no detectable link between droughts and the timing of marriage in high polygyny areas.

This heterogeneity in the relationship between droughts and the timing of marriage is present only in ethnic groups with bride price customs (figure 3). There is no statistically significant association between adverse rainfall shocks and the timing of marriage for women from ethnic groups that do not have bride price customs. This pattern also shows up when I look at unions before age 18 (child marriage) or fertility onset before age 18 (child fertility) as outcomes.

Figure 3: Effect of droughts on the timing of marriage and child marriage

Note: Graph shows the estimated impact of droughts on marriage timing, together with 95% confidence intervals (capped spikes). The estimated coefficients for low and high polygyny areas are statistically different from each other at a 5% significance level for both bride price ethnic group samples.

Effect of food price shocks on the timing of marriage and fertility

Evidence from fluctuations in global food prices confirms that households react in a symmetric way to both positive and negative shocks. Higher international crop price decreases the hazard of child marriage in food-producing areas and increases it in food-consuming areas. The same pattern is observed when I look at the timing of fertility onset.

Policy takeaways

These findings suggest that policies which generate windfall aggregate income can reduce child marriage in monogamous areas, but may have unintended negative consequences for marital outcomes in polygynous areas through funding more second unions in equilibrium, without necessarily decreasing child marriage. Therefore, these types of policies would require further accompanying measures in polygynous areas.

My results also suggest that despite their harmful nature, adverse shocks can also have partially welfare-enhancing effects in polygynous areas, owing to the reallocation of brides from older to younger men. All else being equal, this can lead to better marital outcomes for young girls, but it can also improve the productivity of unmarried young men (Edlund and Lagerlöf 2012, Cameron et al. 2019), while reducing crime and violence (Rexer 2022, Koos and Neupert-Wentz 2020).

References

Ashraf, N, N Bau, N Nunn, and A Voena (2020), “Bride Price and Female Education”, Journal of Political Economy 128(2): 591–641.

Atkinson, M P and B L Glass (1985), “Marital age heterogamy and homogamy, 1900 to 1980”, Journal of Marriage and the Family: 685–691.

Burke, M, E Gong, and K, Jones (2015), “Income Shocks and HIV in Africa”, Economic Journal 125(585): 1157–1189.

Cameron, L, X Meng, and D Zhang (2019), “China’s sex ratio and crime: Behavioural change or financial necessity?”, The Economic Journal 129(618): 790–820.

Carmichael, S (2011), “Marriage and power: Age at first marriage and spousal age gap in lesser developed countries”, The History of the Family 16(4): 416–436.

Collier, P (2017), “Culture, Politics, and Economic Development”, Annual Review of Political Science 20: 111–125.

Corno, L, N Hildebrandt, and A Voena (2022), “Age of Marriage, Weather Shocks, and the Direction of Marriage Payments”, Econometrica 88(3): 879–915.

Edlund, L and N P Lagerlöf (2012), “Polygyny and its discontents: Paternal age and human capital accumulation”, Columbia University Department of Economics Discussion Papers No. 1213-11.

Fenske, J (2015), “African Polygamy: Past and Present”, Journal of Development Economics 117: 58–73.

Jacoby, H G (1995), “The Economics of Polygyny in Sub-Saharan Africa: Female Productivity and the Demand for Wives in Côte d’Ivoire”, Journal of Political Economy 103(5): 938–971.

Koos, C and C Neupert-Wentz (2020), “Polygynous neighbors, excess men, and intergroup conflict in rural Africa”, Journal of Conflict Resolution 64(2-3): 402–431.

Matz, J A (2016), “Productivity, rank, and returns in polygamy”, Demography 53(5): 1319–1350.

McGuirk, E and M Burke (2020), “The economic origins of conflict in Africa”, Journal of Political Economy 128(10): 3940–3997.

Munro, A, B Kebede, M Tarazona, and A Verschoor (2019), “The lion’s share: An experimental analysis of polygamy in northern Nigeria”, Economic Development and Cultural Change 67(4): 833–861.

Rexer, J (2022), “The brides of Boko Haram: Economic shocks, marriage practices, and insurgency in Nigeria”, The Economic Journal 132(645): 1927-1977.

Reynoso, A (2019), “Polygamy, co-wives’ complementarities, and intra-household inequality”, University of Michigan Working Paper.

Tapsoba, A. (2022), “Polygyny and the Economic Determinants of Family Formation Outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa”, TSE Working Paper No. 1240

Tertilt, M (2005), “Polygyny, fertility, and savings”, Journal of Political Economy 113(6): 1341–1371.

World Bank (2015), “World Development Report 2015: Mind, Society, and Behavior”, The World Bank.