Supervisors can nurture talent within organisations by passing on tacit production knowledge that improves workers’ performance. Evidence from Uganda shows that investments in supervisors as coaches can be a cost-effective way to boost worker productivity.

Organisations grow when they effectively motivate, allocate, and nurture their workforce. Both academics and practitioners agree on a key point: frontline supervisors are vital to getting “middle management right” by aligning an organisation’s people with its goals (Mookherjee 2013, Field et al. 2023a, 2023b). In my research, I revisit a core question in organisational economics. How—and to what extent—do supervisors impact worker performance? This matters, as supervision is resource-intensive for both public and private sector organisations (Lazear et al. 2015, Rasul and Rogger 2018). Understanding how supervisors add value can help organisations effectively select, deploy, and plan career paths for them to maximise effectiveness.

What do supervisors do?

Supervisors have many roles. Economists have traditionally viewed them as “monitors” who gather performance information to evaluate, compensate, and reward workers. However, recent research suggests that supervisors may play a broader and more impactful role in identifying, allocating, and retaining talent (Frederiksen et al. 2020, Hoffman and Tadelis 2021, Friebel et al. 2022, Minni 2023).

In new research (Sen 2024), I test if supervisors nurture talent within organisations by passing on tacit production knowledge that improves workers’ performance. Specifically, I investigate if supervisors act as coaches who identify weaknesses and give targeted feedback to their subordinates. To do this, I conducted a field experiment within a leading research organisation in Uganda. This enabled me to study the effects of frontline supervision on the speed and quality of output produced by its workers, whose job it was to conduct household interviews. I assess whether supervisors provide “targeted coaching” by evaluating if the effects of worker supervision are persistent and targeted:

- Persistent effects: If a worker is coached today, they will perform better tomorrow. This will be true even if they are not supervised the next day.

- Targeted effects: Coaching effects will vary across workers, even under the same supervisor. This will depend on workers’ traits that predict initial performance weaknesses. For example, inexperienced workers who typically conduct slower interviews will speed up. Whereas fast but less attentive, experienced workers will now collect higher quality data (though they may slow down).

Measuring survey enumerator performance in Uganda

The field experiment was embedded within a 30-day household agricultural survey run by the partner organisation for a distinct study. I studied the effects of field supervision on the performance of 68 workers who were hired to interview about 50 households each.

Measuring the speed at which workers conduct interviews is relatively simple. Measuring data quality is much harder. However, we can predict where workers are most likely to cut corners based on a questionnaire’s structure. One data-quality measure I study is the number of plot-and-crop observations reported in each interview. This requires a little explanation:

Figure 1 shows a typical household farm plot intercropped with cassava, maize, and beans. To ensure data accuracy, workers had to record crop harvests at the plot level using survey rosters. This meant that each plot-and-crop reported (such as ‘beans were grown on plot A’) triggered approximately four minutes’ worth of questions. Workers could thus speed up interviews by underreporting plot-crops, such as omitting beans from our Figure 1 plot to avoid questions on their harvests, sales, etc. To validate this quality measure I use baseline measures of plot-crops cultivated by these households in a previous agricultural season, as well as re-interviews for a random sample of households.

Figure 1: A household agricultural plot with intercropping

An “insider” experiment in fieldwork supervision

A key aspect of fieldwork is that survey organisations cannot directly observe data quality. However, they can monitor interview quantity and speed remotely. Supervisors fill this gap by conducting unannounced "spot checks" in the field to keep tabs on data quality. They observe a worker conducting an interview, and often advise them on areas for improvement afterwards. Supervisors’ reports on worker performance inform senior management’s decisions on dismissals, rehiring, and promotions. These are often the main incentives for survey enumerators, as they are otherwise paid fixed wages.

Spot checks were central to my study. They ensured workers got individual attention from their direct, more experienced supervisors during fieldwork. I used this to design an experiment with three parts to estimate the effects of supervision on worker performance. In this column, I focus only on the first component in which workers were randomly assigned to spot checks on each survey day (sampling with replacement). This procedure randomly varied the identity of workers who were: (a) assigned to supervision each day, and independently, (b) assigned to high-intensity supervision in the first week of the survey. This enables me to study the persistent effects of week one supervision on the performance of workers in weeks two to five, even on days when they were not supervised.

Main results: Supervisors provide targeted coaching

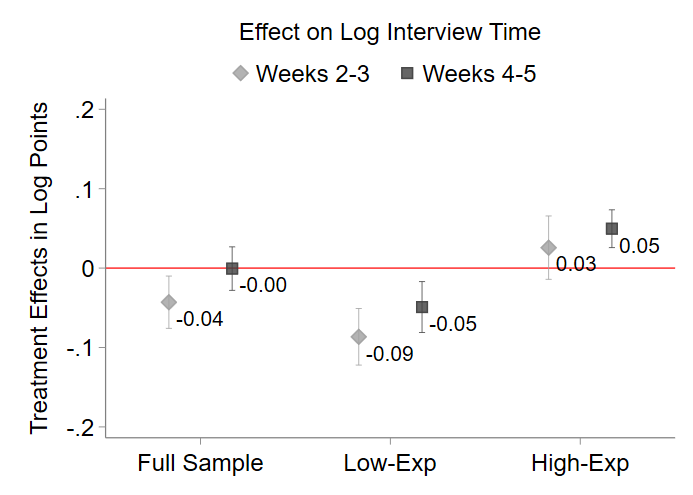

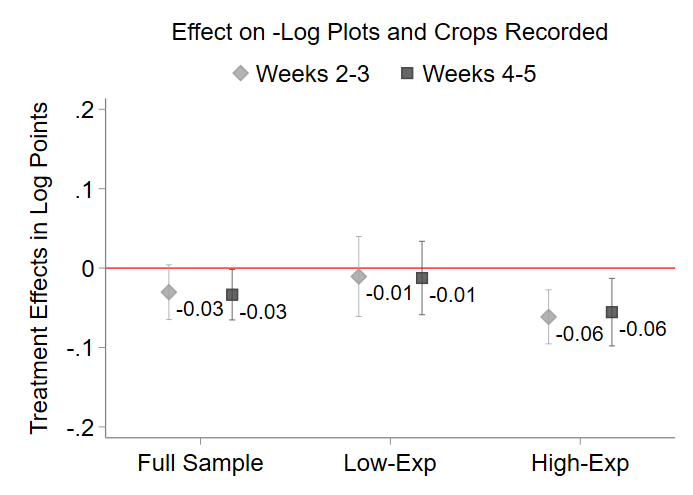

I find that the effects of week one supervision persist through weeks two to five, and they vary with workers’ prior task experience. Following a one-standard-deviation increase in week one supervision intensity or one additional spot check, I find that:

- Inexperienced workers, who initially conducted slower interviews, improve on speed: They decrease their interview completion times by 6.8% (seven minutes) through weeks two to five. The time-savings are immediate and persistent till week five of the survey, although they are more pronounced in the first two weeks (Figure 2a). Moreover, there are no statistically significant changes in the number of plots-and-crops they report in each interview (Figure 2b).

- Fast, experienced workers, record higher quality data but slow down: The number of plot-crops they report increases by 5.3% per interview. Following one extra spot visit in week one, these workers record 31 more plot-crops over the 40 interviews they conduct in weeks two to five. But their interview completion times also increase by 3.9% (3.6 minutes).

- On average, we observe a significant decrease in interview times in weeks two to three of the survey, but not in weeks four to five (when high-speed workers slow down). The number of plot-crops recorded by the average worker increases by 3% through weeks two to five.

We conduct a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation to compute the magnitude of these effects at the organisation-level. Every hour that supervisors invest in coaching workers during the first week yields a net increase in value worth 2.3 worker-hours. Supervisors are paid 15% more than workers in our setting, implying that the benefit-to-cost ratio of a supervisor-hour is 2. The gains could be even larger if supervisor time was allocated optimally across workers. In a nutshell, investments in supervisors (as coaches) are very cost-effective for our partner organisation. I use additional components of the experimental design to distinguish between coaching and alternate causal mechanisms such as workers’ incentives.

Figure 2: Persistent effects of week one supervision by project phase

Note: 90% confidence intervals shown.

Takeaways for personnel policies

The view that supervisors are conduits for the transmission of production knowledge in organisations has clear implications for personnel policies. I conclude with some suggestions for how organisations should select and nurture supervisors.

- Selection and training: Effective supervisors require a deep understanding of the industry, and the tasks they oversee. Tacit knowledge is a cornerstone for delivering tailored coaching.

- Career incentives: Organisations should design career paths that nurture supervisors’ coaching skills. It may be a mistake to reward supervisors who nurture talent with promotions to strategy roles in senior management that do not harness these skills (yet this is something that organisations do routinely).

- Early coaching: Early coaching for new employees may also yield substantial performance gains.

Editor’s Note: A version of this article first appeared on Economics that Really Matters and in an International Growth Centre Policy Brief.

References

Alchian, A A, and H Demsetz (1972), “Production, information costs, and economic organization,” The American Economic Review, 62(5): 777–795. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1815199

Field, E, B Hancock, and B Schaninger (2023a), “Middle managers are the heart of your company,” The McKinsey Quarterly.

Field, E, B Hancock, M Mugayar-Baldocchi, and B Schaninger (2023b), “Stop wasting your most precious resource: middle managers,” McKinsey & Company Insights, March 2023.

Frederiksen, A, L B Kahn, and F Lange (2020), “Supervisors and performance management systems,” Journal of Political Economy, 128(6): 2123–2187.

Friebel, G, M Heinz, and N Zubanov (2022), “Middle managers, personnel turnover, and performance: A long-term field experiment in a retail chain,” Management Science, 68(1): 211–229.

Hoffman, M, and S Tadelis (2021), “People management skills, employee attrition, and manager rewards: An empirical analysis,” Journal of Political Economy, 129(1): 243–285.

Lazear, E P, K L Shaw, and C T Stanton (2015), “The value of bosses,” Journal of Labor Economics, 33(4): 823–861.

Minni, V M L (2023), “Making the invisible hand visible: Managers and the allocation of workers to jobs,” Working Paper.

Mookherjee, D (2013), “Incentives in hierarchies,” in R Gibbons and J Roberts (eds), The Handbook of Organizational Economics (pp. 764–798). Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400845354-021

Rasul, I, D Rogger, and M J Williams (2021), “Management, organizational performance, and task clarity: Evidence from Ghana’s civil service,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 31(2): 259–277.

Sen, R (2024), “Supervision at work: Evidence from a field experiment,” Working Paper.