Targeting women directly with relevant information in ways that are appealing increases their agency, access to resources, and achievements in farming

In many developing countries, women often have limited ability to make important strategic choices, let alone transform those choices into desired action and outcomes. Research suggests that targeting women with relevant information in formats that are both accessible and appealing can change this reality. However, all information campaigns are not equally successful. Often, seemingly small design attributes can have substantial impacts on effectiveness. Interest is growing in understanding how the content, format, sources, and targeting of information affect empowerment. For example, the influence of role models on women’s decision-making and empowerment is potentially important in information campaigns (Porter and Serra 2020, Riley 2017).

Empowering women in agriculture

In the smallholder agriculture systems found in many developing countries, women work long days in the field but rarely have a voice in major decisions. These can include what crops to grow, which technologies and inputs to use, and whether to consume or sell crops. One constraint to women’s influence is asymmetric information between spouses regarding the existence and application of productivity-enhancing technologies and practices (Magnan et al. 2015). When women possess less information, they are less able to participate in decision-making processes on the farm (Fisher and Carr 2015). Targeting women with information that reduces such asymmetries may therefore be empowering.

The source of information may also contribute to women’s empowerment in agriculture. Prior studies capture this by studying the singular and combined influence of social learning, peer effects, social identification, and gender homophily (a tendency of people to align with others of the same gender and background) (e.g. BenYishay and Mobarak 2019, Beaman and Dillon 2018). Targeting women with information conveyed by women of similar characteristics may be a further channel for empowerment.

Yet, very few of these ideas find their way into practice. Agricultural extension systems in developing countries tend to target male farmers with information that is rarely tailored to their female counterparts. A recent survey on public service delivery in Uganda found that only 16% of extension agents are women. This suggests that the extension system does not sufficiently recognise the gendered power dynamics governing intra-household information exchanges. This serves to reinforce the disempowerment of women in agricultural decision-making processes.

Testing cognitive and behavioural channels

To investigate the consequences of male-biased services, we designed an experiment in eastern Uganda involving 3,300 smallholder maize-farming households that varied both the provision of and exposure to information by gender (Lecoutere et al. 2019). We produced videos consisting of a 10-minute inspirational story in which a farmer (a man, a woman, or a couple) recount how they used to struggle with low maize yields. The videos include information about a range of productivity-enhancing strategies and discuss the costs and benefits of the different practices and inputs being promoted. They also recommend that viewers take a long-term perspective on improving their maize cultivation by starting small and reinvesting profits on increasingly large areas of land. We further varied who saw the videos in the participating households: the male co-head, the female co-head, or the co-heads together.

Receiving information empowers women

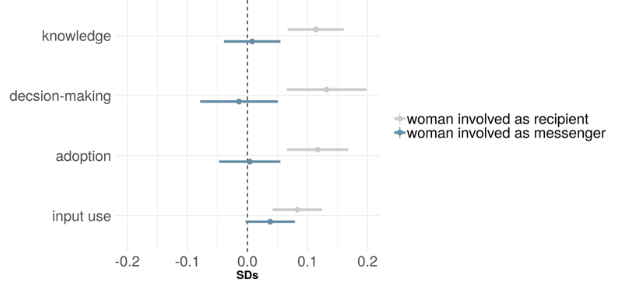

We find that targeting women within the household (as opposed to only the male co-head) with extension information has a positive effect on different domains of empowerment. This includes women’s knowledge of agronomic practices, their participation in agricultural decision-making, and their adoption of recommended practices and inputs. This is illustrated in figure 1 below, which shows average treatment effects for indices created for these four groups of outcomes. Our analysis also reveals positive effects on production-related outcomes, such as maize yield, as well as market participation.

Figure 1 Effect of involving women as recipient of information and as messenger

Most of the impact on women empowerment seems driven by the women who received the information alone, suggesting that both male and female co-heads tend to monopolise information. Whilst there is some evidence that the women who received information together with their husbands somewhat increased cooperation within the household , the effects are much weaker.

Changing perceptions

The empowerment impacts of involving women as messengers, the role model effect, seem more complicated. While we find no effect on women’s knowledge, decision-making, or adoption of recommended agronomic practices, involving women as messengers may lead to an increase in women’s use of organic fertiliser.

Looking only at households where women co-heads were targeted, we find that if these women were shown a video featuring a woman proving the information, they are more likely to take the lead in decision making. This suggests that gender homophily may be at work. Furthermore, we find that if men were shown a video featuring a woman, they are less likely to make decisions unilaterally. This suggests that involving women as messengers may have challenged beliefs and stereotypes about women being less able to make decisions related to agriculture (Beaman et al. 2009).

Policy implications: Providing information to women can empower them

Most extension strategies target the male household head, implicitly assuming that a married woman’s interaction with her husband will provide her with the necessary information on agriculture. Yet, this assumption relies on the alignment of preferences of male and female co-heads, sharing of household resources including information, and cooperation that means households reach Pareto-optimal outcomes (Fletschner and Mesbah 2011). Our research adds to the large empirical literature that rejects this assumption.

Three key policy recommendations follow from our study:

- To empower women at an individual level, boosting yields on plots that they autonomously manage, information should be provided to them directly and this can lead to considerable returns.

- To empower women in collaboration with their male household co-heads, information should be provided to them together and this could contribute to greater involvement of women in joint decision-making and joint action. However, this may not translate into better agricultural outcomes on jointly managed plots, increases in joint sales, or improvements in women’s independent agricultural outcomes.

- Featuring women as role models in information campaigns may be useful in reducing men’s dominance in the domain of agriculture, and therefore can create opportunities for greater involvement of women. Including women as role models in information campaigns targeted at women can stimulate women’s individual decision-making and action.

References

Beaman, L, R Chattopadhyay, E Duflo, R Pande and P Topalova (2009), “Powerful women: Does exposure reduce bias?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124 (4): 1497–1540.

Beaman, L and A Dillon (2018), “Diffusion of agricultural information within social networks: Evidence on gender inequalities from Mali”, Journal of Development Economics, 133: 147–161.

BenYishay, A and A Mobarak (2019), “Social learning and incentives for experimentation and communication”, Review of Economic Studies, 86 (3): 976–1009.

Fisher, M and E Carr (2015), “The influence of gendered roles and responsibilities on the adoption of technologies that mitigate drought risk: The case of drought-tolerant maize seed in Eastern Uganda”, Global Environmental Change, 35: 82–92.

Fletschner, D and D Mesbah (2011), “Gender disparity in access to information: Do spouses share what they know?”, World Development, 39 (8): 1422–1433.

Lecoutere, E, D Spielman and B Campenhout (2019), “Women’s empowerment, agricultural extension, and digitalisation: Disentangling information and role model effects in rural Uganda”, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Discussion Paper 1889..

Magnan, N, D Spielman, K Gulati and T Lybbert (2015), “Information networks among women and men and the demand for an agricultural technology in India”, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Discussion Paper 1889.

Porter, C and D Serra (2020), “Gender differences in the choice of major: The importance of female role models”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics (forthcoming).

Riley, E (2017), “Role models in movies: The impact of Queen of Katwe on students’ educational attainment”, CSAE Working Paper Series 2017-13, Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford, Oxford.