Merit-based financial aid for low-income students doubles immediate postsecondary enrollment, making elite universities substantially more diverse

There is clear evidence that students from disadvantaged backgrounds are severely underrepresented in the postsecondary pipeline worldwide, particularly at selective universities (Chetty et al. 2017, Ferreyra et al. 2017, Hoxby and Avery 2013). While high-income countries may offer extensive financial aid and student loan programmes to high-achieving and low-income students, such aid policies are more recent in the developing world. In countries like Colombia, binding credit constraints for low-income students and relatively pricey top-ranked private higher education institutions (HEIs), result in a steep enrollment gradient by socioeconomic status (SES). It is precisely in these settings where financial aid has its largest enrollment potential.

Upstream and downstream impacts of financial aid: Colombia’s Ser Pilo Paga programme

We study the impact of transitioning from a setting with very little financial aid to one with full scholarship-loans for high achieving, low-income students (Londoño-Velez et al. forthcoming). We exploit a large-scale programme introduced in Colombia between 2014 and 2018 called Ser Pilo Paga (SPP). SPP was announced in October 2014, two months after 575,000 students sat for Colombia’s national standardised high school exit exam, SABER 11.

To be eligible, students must be:

- Extremely high achieving i.e. score in the top 9% of SABER 11, which, unlike the SAT in the US, is taken by virtually all high school seniors.

- Low-income i.e. belong to the poorest 50% of households, as measured by SISBEN, Colombia’s main proxy means-testing system for social assistance.

- Admitted to a “high-quality” university, of which there were 33 certified by the Colombian government at the time of the policy announcement i.e. less than 10% of HEIs.

SPP has four key characteristics:

- It is highly visible and has simple, easy-to-understand eligibility rules and application procedures. Students are readily able to ascertain their own aid eligibility from their test score and household wealth index.

- It is generous. It covers the full tuition cost of attending an undergraduate programme in any “high-quality” university in Colombia, as well as a modest maintenance stipend.

- It is large in scale. SPP annually benefits roughly one-tenth of first-year postsecondary enrolees and one-third of those entering “high-quality” universities immediately after graduating high school.

- It is highly predictive of overall access to financial aid. This is because low-income students in Colombia, as in other developing countries (Solis 2017), have little alternative sources of aid.

The impacts of financial aid on enrollment and college choice

We exploit SPP’s sharp merit and need requirements to identify impacts on enrollment and college choice. We focus on the first cohort, who cannot manipulate nor influence their scores around the eligibility cut-offs. This is because SPP was announced after they took the national standardised exam and there was no time to request a re-evaluation of their household wealth index.

Very large immediate enrollment impacts of financial aid

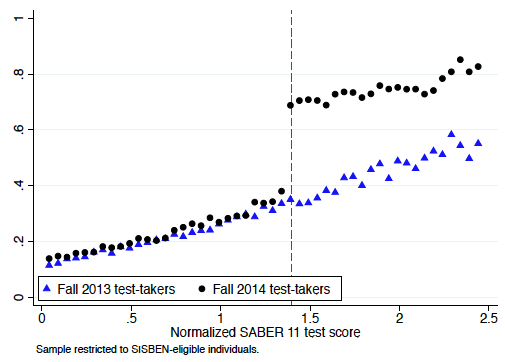

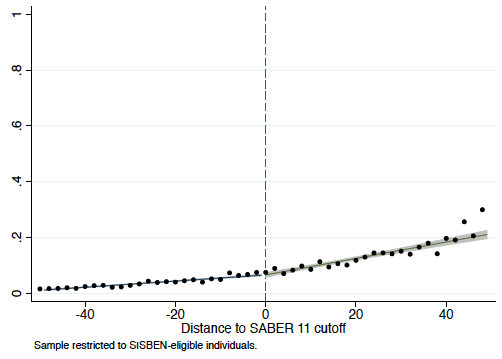

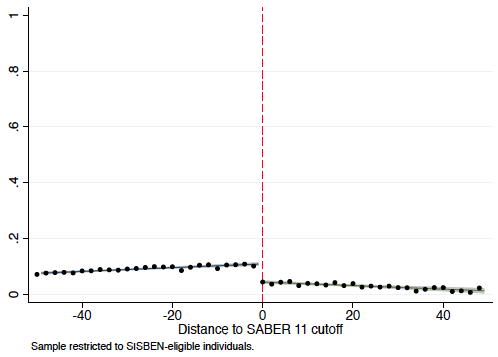

For need-eligible students, having a test score just above the merit cut-off raises immediate enrollment by 32 percentage points or 86.5% (Figure 1, Panel A). For merit-eligible students, crossing the need cut-off raises immediate enrollment by 27.4 percentage points or 56.5% (Figure 1, Panel B).

Figure 1 Large impact of financial aid on immediate postsecondary enrollment

Panel A: SABER 11 test score as running variable

Panel B: SISBEN wealth index as running variable

Note: These figures plot the probability of immediately accessing any HEI for test-takers in Fall 2013 (before SPP) and Fall 2014 (after SPP) as a function of the normalised SABER 11 score (Panel A) and the SISBEN (Panel B) eligibility cut-offs.

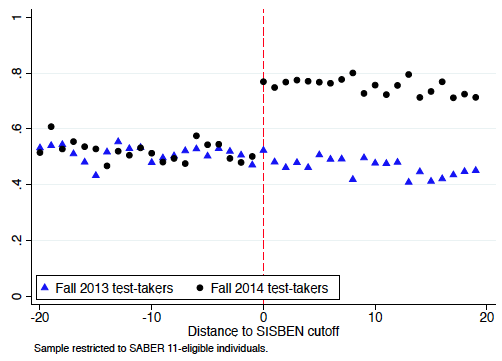

These massive enrollment impacts virtually eliminated the SES enrollment gradient among high-performing test-takers (Figure 2).

Figure 2 The enrollment gap disappeared among top decile test-takers

Note: This figure presents the probability of immediately enrolling in any HEI among SABER 11-eligible test-takers aged 14–23 in Fall 2013 (before) and Fall 2014 (after) by socioeconomic “stratum”, which refers to the Colombian socioeconomic stratification system (stratum one is the poorest; stratum six is the wealthiest).

Moreover, financial aid substantially altered students’ college choices, shifting students from low- to high-quality HEIs. For instance, among need-eligible students, crossing the test score cut-off lowers enrollment at low-quality HEIs by 15.4 percentage points (57.7%) and raises enrollment at high-quality HEIs by 46.5 percentage points (426.6%). This significantly improves students’ college education quality because, as we show, high-quality HEIs have higher-ability students, more resources, and better graduation rates, among others.

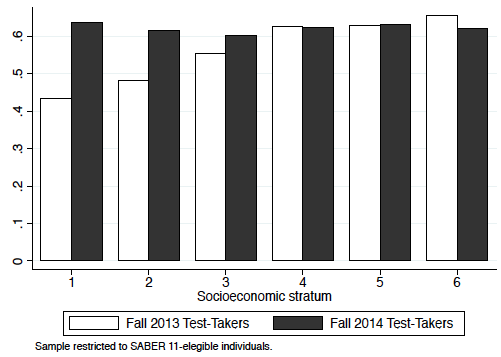

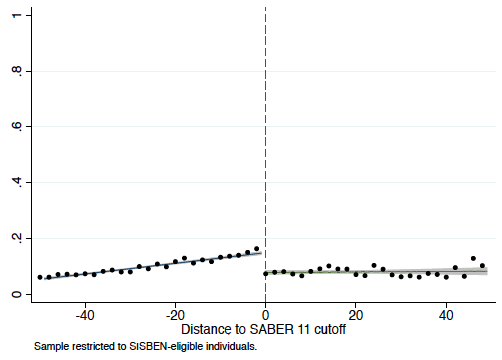

Importantly, students disproportionately chose to enrol in private over public high-quality HEIs (Figure 3). This student sorting into private education is not explained by a differential quality accreditation status. Instead, and consistent with previous literature (Riehl et al. 2016), our survey evidence suggests students perceive private schools as more prestigious and producing greater value added—broadly defined—for students.

Figure 3 Immediate postsecondary enrollment: High- vs. low-quality, private vs. public institutions

Panel A: Private high quality HEI

Panel B: Public high quality HEI

Panel C: Private low quality HEI

Panel D: Public low quality HEI

Note: The figures plot the probability of immediate enrollment in a private or public, high- or low-quality HEI, as a function of the distance to the SABER 11 test eligibility cut-off. The sample is restricted to SISBEN-eligible students.

The broader effects of financial aid on students eligible and ineligible for aid

Such a massive enrollment impact on eligible students might, however, have no impact on overall enrollment if seats are fixed and recipients simply displace other prospective students from colleges. Alternatively, aid might induce both demand and supply side effects that alter and perhaps improve outcomes for non-recipients too, producing a net social gain. To explore these broader upstream and downstream effects of aid, we compare cohorts that are more or less exposed to financial aid expansion across time.

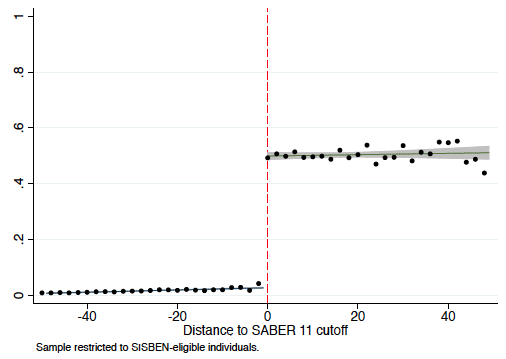

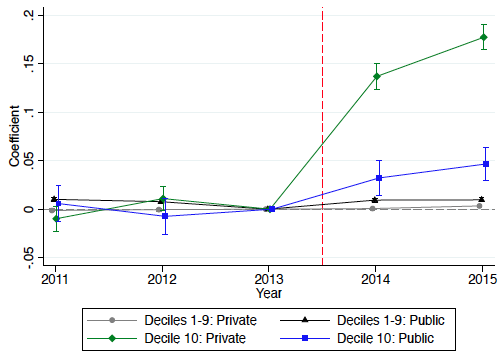

We see an overall increase in immediate enrollment. The demand for private high-quality undergraduate education skyrocketed following the expansion of financial aid, and these institutions responded by admitting and enrolling more students (Figure 4A). Moreover, as aid recipients sorted out of low-quality HEIs, the empty seats left were filled by low-income, lower-performing applicants i.e. students from deciles nine and below (Figure 4B). That is, financial aid also raised college attendance for students ineligible to receive aid.

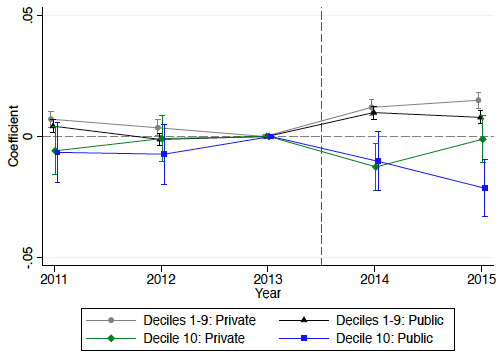

Figure 4 Low-income students’ enrollment by SABER 11 decile and HEI type

Panel A: High-quality HEIs: Private vs. public

Panel B: Low-quality HEIs: Private vs. public

Note: These figures plot, for low-income students (socioeconomic strata one to three), the difference in immediate enrollment separately by test score decile and HEI type between Fall (treatment) and Spring (control) test-takers before and after SPP is introduced (red vertical line).

An increase in diversity

As low-income high-achievers sorted into private high-quality HEIs, the student body composition at these institutions changed dramatically. Student quality and socioeconomic diversity significantly increased, with the share of low-income entering students increasing by a staggering 46% at these HEIs. Thus, by relaxing their credit constraints, financial aid enabled low-income high-achievers to access expensive HEIs historically reserved for those who could afford them. In contrast, average student quality dropped at low-quality HEIs. Ability stratification therefore largely replaced wealth stratification in postsecondary schooling as a result of financial aid.

The exodus of high-ability aid beneficiaries from low-quality HEIs put pressure on these colleges to become more efficient and obtain High Quality Accreditation to attract high-achievers. However, the number of HEIs awarded High Quality Accreditation has only gradually increased over the last three years, and whether or not this reflects an actual quality improvement remains to be seen.

Lastly, relative pre-collegiate achievement improved among very low-income high school students following the expansion of aid. Comparing relative test performance among 2.7 million test-takers between 2012 and 2016 by socioeconomic background, we show that very low-income students are 32% more likely to score in the top decile and 175% more likely to score in the top percentile two generations after policy rollout (see also Laajaj et al. 2018).

Conclusion

Our findings shed light on the vast range of upstream and downstream effects from the SPP programme, helping to inform policymakers in similar countries that are seeking to address socioeconomic inequality and promote equal opportunity by levelling access to high-quality universities. In the long-run, SPP is likely to have important impacts on education and labour markets in Colombia, far beyond the ones analysed here. Studying these impacts will undoubtedly come in time when the required data becomes available.

References

Chetty, R, J Friedman, E Saez, N Turner and D Yagan (2017), “Mobility report cards: The role of colleges in intergenerational mobility”, Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Working Group.

Ferreyra, M, C Avitabile, J Botero, F Haimovich and S Urzua (2017), At a Crossroads: Higher education in Latin America and the Caribbean, The World Bank.

Hoxby, C and C Avery (2013), “The missing “one-offs”: The hidden supply of high-achieving, low- income students,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

Laajaj, R, A Moya and F Sanchez (2018), “Motivational effects of a nation-wide merit scholarship for low-income students: Quasi-experimental evidence from Colombia”, Documento CEDE, 26.

Londoño-Vélez, J, C Rodriguez and F Sanchez (forthcoming), “Upstream and downstream impacts of college merit-based financial aid for low-income students: Ser Pilo Paga in Colombia”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

Riehl, E, J Saavedra and M Urquiola (forthcoming), “Learning and earning: An approximation to college value added in two dimensions”, in Productivity in higher education, Hoxby, C and K Stange (eds.).

Solis, A (2017), “Credit access and college enrollment,” Journal of Political Economy, 125 (2): 562–622.