Evidence from Indonesia shows school construction improves labour and marriage market outcomes, and benefits are transmitted intergenerationally

Governments in developing countries spend approximately one trillion dollars annually on education, and households are estimated to spend hundreds of billions more on the education of their children (Glewwe and Muralidharan 2016). Government education spending can take many forms, including teacher interventions, school input programmes, cash transfer programmes, and of course a common and direct form of education spending, namely, school construction (see Burde and Linden 2013 and Kazianga et al. 2013 for short-term evaluations from Afghanistan for Burkina Faso, respectively). The question of which adult outcomes are affected by increases in educational attainment and whether these effects persists into the next generation are of great policy importance and broad research interest.

While these government programmes are often motivated by the belief that increases in education will translate to higher economic development and growth, the causal effect of schooling on economic growth is not uncontested. It is also hard to estimate because the choice of how much education to obtain is correlated with a large number of individual, household, and community characteristics. In recent years, major strides have been made using randomised experiments, but the vast majority of evaluations take place shortly after the intervention has ended (McEwan 2015) so the question remains whether the effects persist or fade out over time.

Estimating the causal impact of primary school construction in Indonesia

In recent work (Akresh et al. 2018), we study the causal impact of one of the largest primary school construction programmes ever completed on a wide range of long-term and intergenerational outcomes, many of which have not been studied before. Between 1973 and 1979, the Indonesian government constructed over 61,000 primary schools, almost doubling the number of primary schools. We use 2016 nationally representative data from Indonesia that contain information on a wide range of outcomes related to education, employment, migration, living standards, taxes, and marriage outcomes. We use a difference-in-differences estimation strategy, as in Duflo (2001), exploiting variation across geographic districts in the number of schools built and across birth cohorts in their exposure to the schools.

Long-term effects of education

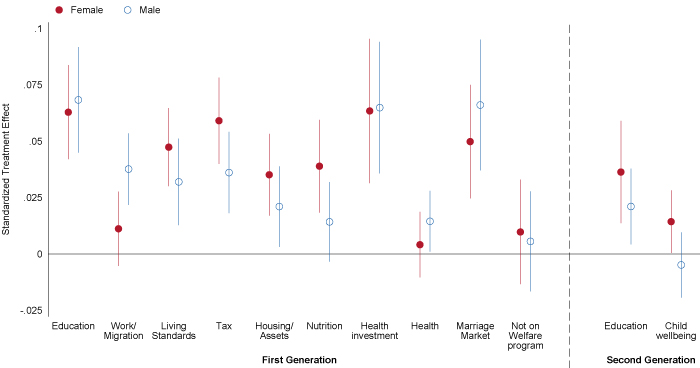

Figure 1 summarises the main findings and shows large improvements across broad families of outcomes, each combined in an index following Kling et al. (2007). School construction, not surprisingly, leads to improved educational outcomes. Duflo (2001) previously showed this for men, and we confirm it also improves women’s education. As adults, men exposed to school construction are more likely to be employed, to work in the formal sector, to work in the non-agricultural sector, and to migrate. Women exposed to school construction are more likely to migrate and have fewer children. Households in which either parent is exposed to school construction have higher living standards, better housing, more assets, and pay more government taxes. While nutrition and health investments increase, we do not observe any improvements in health outcomes. School construction leads to improved marriage market outcomes with spouses being more educated, more likely to be literate, and more likely to have migrated.

Figure 1 Effect of school construction on indexes of long-run and intergenerational outcomes

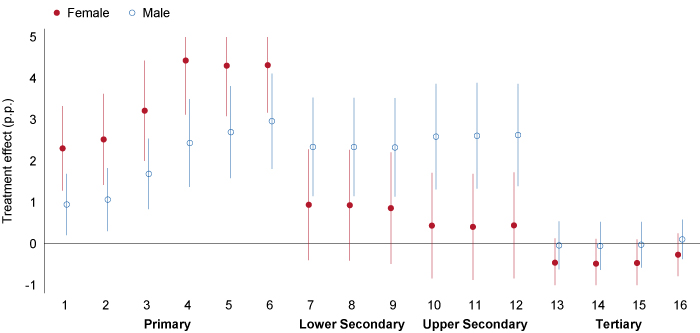

In Figure 2, we highlight the gender dynamics of the effects of school construction on education. The figure shows the change in the likelihood of completing at least a certain number of years of education. This figure shows that for women, the effects are concentrated in primary school, while for men the effect extends throughout lower and upper secondary school.

Figure 2 Effect of school construction on the probability of first-generation individual attending at least n years of schooling

Intergenerational effects of education

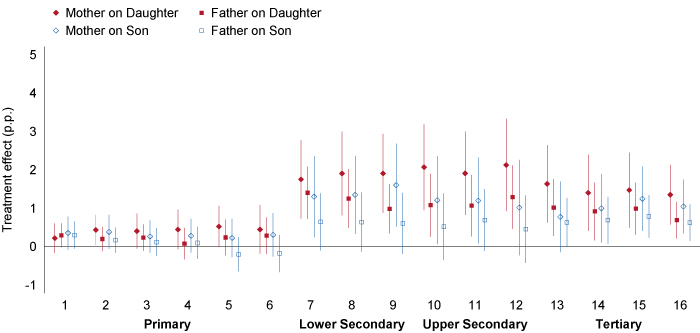

Parents exposed to school construction transmit these benefits to the next generation. Figure 3 shows the likelihood of a second-generation child completing at least a certain number of years of school. We explore the effects depending on whether the father or mother is exposed to school construction and whether their child is a son or daughter. We observe no effects during primary school because primary school is almost universal when second-generation individuals attend school. The effects extend throughout secondary and tertiary education. Relative to baseline levels, the largest impacts are seen in tertiary education with effect sizes indicating a 20% to 25% increase in the likelihood of the second-generation child completing university.

Figure 3 also reveals important gender differences. Parental exposure has larger impacts for daughters than for sons, and a mother’s exposure to school construction has a larger intergenerational impact than a father’s exposure.

Figure 3 Effect of school construction on the probability of second-generation individual attending at least n years of schooling

By extending the focus on men in Duflo (2001) to study the impact of school construction on women, we now observe gender differences for both first- and second-generation outcomes. We perform a detailed mediation analysis to explore the mechanisms that drive the intergenerational transmission of schooling. Marriage market outcomes appear to a play a crucial role, particularly whether the spouse has completed primary school, is literate, works in the formal sector, or works outside of agriculture.

Policy implications: Rate of return and fiscal impacts of school construction

To quantify the policy implications, we conduct a cost-benefit analysis in which we create an accounting model to calculate the costs of school construction and subsequent discounted benefits for the government in terms of increased tax revenues and overall improved living standards for the Indonesian population. Our cost-benefit analysis highlights that under all reasonable assumptions school construction pays for itself in terms of additional expected government tax revenues, not to mention the additional benefits of improved living standards.

Furthermore, given the observed intergenerational transmission of education, the likely long-run benefits are vast. Across a range of different parameter estimates, we find that school construction leads to increased government tax revenues that directly offset construction costs in most cases within 40 years. Furthermore, accounting for improved living standards of the Indonesian population reveals high internal rates of return ranging from 13-21% and benefits surpassing costs within 17-30 years after the schools were built. These results provide strong support for the cost-effectiveness of school construction interventions.

To gain additional insight into the intergenerational transmission of education, we perform an exploratory analysis calculating the intergenerational elasticity (IGE) of education between children and parents. In policy circles, especially in developing countries, there is considerable debate about the optimal amount of intergenerational mobility. High mobility suggests equality of opportunity whereby a parent’s outcome does not mechanically determine the child’s, but it is critical to understand the mechanisms driving that intergenerational correlation (see Black and Devereux (2011) for a discussion of this literature). Low mobility that is due to differential access to schooling suggests that public policy can play a role in equalising opportunities. Comparing the IGE across high and low programme intensity areas and between young and old cohorts in our Indonesian data, we find there is an increase in mobility for children whose parents are exposed to school construction, highlighting the realised benefits of this government education policy.

References

Akresh, R, D Halim and M Kleemans (2018), “Long-term and intergenerational effects of education: Evidence from school construction in Indonesia.” NBER Working Paper 25265.

Black, S and P Devereux (2011), “Recent developments in intergenerational mobility”, in O Ashenfelter and D Card (eds), Handbook of Labor Economics 4, Elsevier, pp. 1487-1541.

Burde, D and L Linden (2013) “Bringing education to Afghan girls: A randomized controlled trial of village-based schools.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5(3): 27-40.

Duflo, E (2001), “Schooling and labor market consequences of school construction in Indonesia: Evidence from an unusual policy experiment”, American Economic Review, 91(4): 795-813.

Glewwe, P and K Muralidharan (2016), “Improving education outcomes in developing countries: Evidence, knowledge gaps, and policy implications”, Handbook of the Economics of Education 5, Elsevier.

Kazianga, H, D Levy, L Linden and M Sloan (2013) “The effects of ‘Girl-Friendly’ schools: Evidence from the BRIGHT school construction program in Burkina Faso.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5(3): 41-62.

Kling, J, J Liebman and L Katz (2007), “Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects”, Econometrica, 75(1): 83-119.

McEwan, P (2015), “Improving learning in primary schools of developing countries: A meta-analysis of randomized experiments”, Review of Educational Research, 85(3): 353-394.