The impacts of a school feeding programme in Colombia go beyond school attendance and hunger relief, fostering learning, high school graduation and tertiary enrolment.

The past two years have seen an unprecedented global food security crisis (World Bank 2024). Almost 350 million people are at risk of starvation, with children and youth comprising almost 40% of this group. Poor nutrition, united with the school closures and the impact of COVID on health and safety nets, has led governments and NGOs to declare a state of global education crisis (UNESCO, UNICEF, World Bank).

Not surprisingly, school feeding programmes have become one of the most widely used social interventions to combat poverty and hunger and promote school attendance. By 2023, around 41% of all children enrolled in primary education worldwide benefited from a free or subsidised meal in their schools, a percentage that increases to 61% in high income countries (WFP 2023). Despite their widespread implementation, research on the impacts of these programmes concentrates on high-income countries and short-term outcomes, mostly related to health indicators and school attendance (see Wang et al. 2021 for a recent systematic review). A few recent studies have also analysed their effects on learning outcomes for elementary and middle school students (Anderson et al. 2018, Chakraborty et al. 2019, Gordanier et al. 2020, Ruffini 2022)

In recent research, we contribute to this literature by studying the impact of Colombia's nationwide school feeding programme on medium and long-term educational outcomes, including grade repetition and school dropout, high school graduation, academic performance and access to higher education. Utilising four comprehensive administrative datasets spanning seven years and covering over 14 million public school students in the country, we implement a staggered difference-in-differences model as our main identification strategy. This approach compares the programme’s effects on each cohort separately, using grades who never receive the programme, or have not yet receive the programme, as controls in line with recent methodologies (Bilinski et al. 2023, Callaway et al. 2024).

The school feeding programme in Colombia

The “Programa de Alimentación Escolar” (PAE) provides a food supplement during the school day and throughout the school year to all students attending public schools in Colombia. The programme, which started its current structure in 2006 under the Colombian Institution for Family Welfare, was run since 2011 by the Ministry of National Education under a decentralised implementation model at the regional and local level. In a first stage, regional and local authorities select the beneficiary schools based on Ministry of National Education guidelines, prioritising full-day schools, rural schools, urban schools with ethnically diverse and disabled populations, and urban schools with high concentrations of impoverished students. Once the schools are selected, students who will receive the free meals are identified. Selection begins with students in full-day schools (both rural and urban), students from rural areas, and within these two groups students in kindergarten and primary education, and finally, those in secondary and high school. Priority is given to students from ethnic minorities, those with disabilities, and those from poor or conflict-affected families. Then, authorities select the operators of the programme and define menu cycles and supply delivery routes. Finally, local education authorities, special auditors, and parents' associations oversee the programme's implementation to ensure compliance.

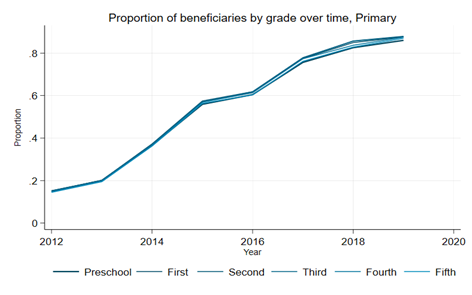

The PAE experienced significant growth between 2012 and 2019. In 2012, only 23% (10,425) of public schools had at least one student receiving a school meal, but by 2019, this percentage had increased to 96% (42,773). Similarly, the number of beneficiaries rose from 810,000 students (10% of total enrollment) to 5.6 million students (73%) during this period, providing 6.48 million daily food rations. Figure 1 illustrates the programme's expansion across the country’s primary schools (panel A), showing that within a given school, all or none of the students in a grade level benefit from the programme (panel B). Expansion of PAE across secondary grades is very similar. Therefore, while the selection of beneficiary schools is not independent of the schools' characteristics, the variation in the rate of PAE beneficiaries within grades of the same school is essentially binary, depending on the resources allocated to the programme by the central government.

Figure 1: Density of the proportion of beneficiaries by grade

Panel A Panel B

Source: SIMAT, authors' calculation, 2024.

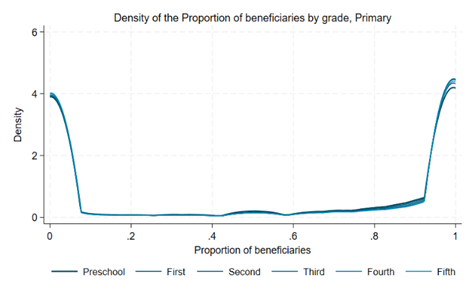

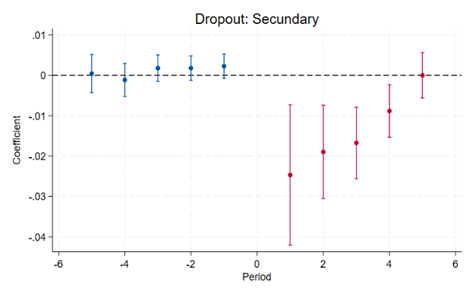

Impacts of the school feeding programme on school dropout and grade repetition in Colombia

Using the PAE's expansion across school grades, we compare the repetition and dropout rates of treated cohorts—those where at least 5% of students began receiving PAE in a given year—against never-treated and not-yet-treated grades. As with all difference-in-differences (DID) estimation strategies, a key assumption is that the treated and control groups follow parallel trends before treatment. Figure 2 provides evidence supporting this assumption by comparing the dropout rates for primary and secondary education between treated and control grades within schools, before and after implementation started. As observed, no differences in dropout rates are detected before treatment, while afterwards, the trends begin to diverge, giving credence to our identification strategy.

Figure 2: Event study parallel trends assumption

Panel A Panel B

Note: Grade specific, school and time fixed effects are included in the regression. Source: SIMAT, authors' calculation, 2024.

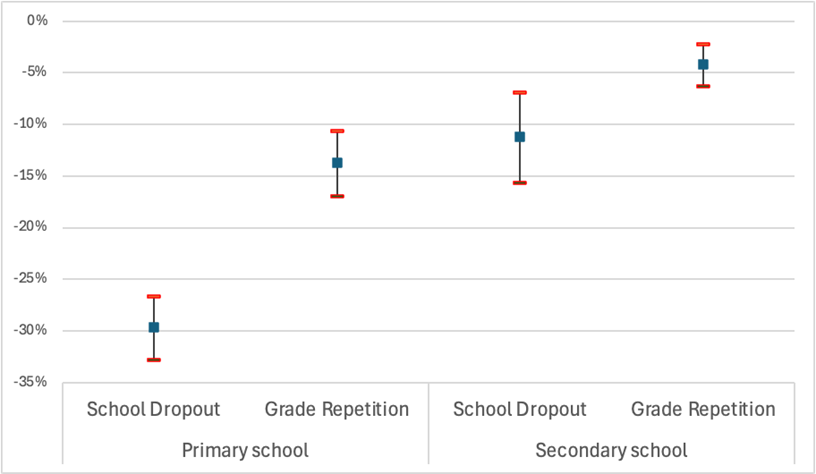

Thus, implementing a staggered DID strategy, we find compelling evidence that PAE reduces both grade repetition and school dropout rates in primary and secondary education. In control grades, the average rates for grade repetition and dropout in primary education are 12.4% and 6.4%, respectively, while in secondary education, they are 9.5% and 8.9%. Our analysis shows that grades receiving the programme see reductions between 0.05 and 0.02 percentage points. Figure 3 summarises these results, assuming that PAE exposure in each grade increases from zero to full coverage. The findings indicate that PAE reduces grade repetition and dropout rates by 30% and 14%, respectively, relative to control means in primary education, and by 11% and 4% in secondary education.

Figure 3: Average impact on school drop-out and grade repetition

Note: the figure shows the average impact on school dropout and grade repetition as a percentage of the mean of the control group, derived from a staggered difference-in-differences estimation procedure. The average impact, along with the 95% confidence interval for each outcome of interest, is presented. Source: SIMAT, authors' calculation, 2024.

Impacts on educational achievement of the school feeding programme in Colombia

The primary objective of school feeding programmes globally is to increase school retention and alleviate hunger. However, the true measure of success of these programmes should extend beyond these goals, encompassing improvements in school completion, access to higher education, and learning outcomes. The available administrative data allows us to address these broader questions. To do so, we analyse information from two student cohorts that began secondary education (sixth grade) in 2012 and 2013, and who, with an on-time trajectory, were expected to complete high school in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

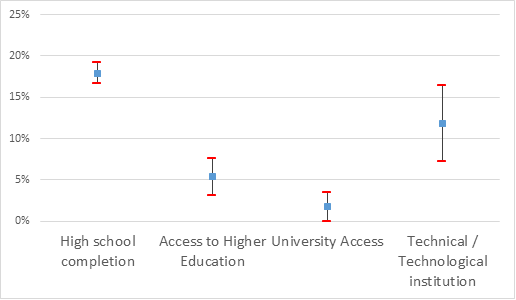

Figure 4 presents our main results. School-fed students are 11 percentage points more likely to complete high school, as proxied by taking the Saber 11 exam, which corresponds to an increase of nearly 18% compared to non-beneficiaries given a baseline level for controls of 63%. Furthermore, although not displayed, we also find that learning outcomes improve for beneficiary students. Using scores from the Saber 11 exam, which is comparable to the SAT in the United States, we observe that PAE participation boosts the academic performance of low-achieving students, while the impact on high-achieving students is negligible or even slightly negative. These positive outcomes translate into greater access to tertiary education. As shown in Figure 4, students who received PAE in secondary education are two percentage points more likely to enter higher education than non-PAE students, representing a 5% increase over the latter group’s average access rate (35%). The impact is concentrated in access to technical and technological institutions, with an additional 1.5 percentage points, or a 12% increase over non-PAE students (13%). However, the impact on access to universities is not statistically significant.

Figure 4: Average impact on high-school completion and access to tertiary education

Note: The figure shows the average impact on high school completion and access to tertiary education for students who in 2012 and 2013 started sixth grade. The average impact, along with the 95% confidence interval for each outcome of interest, is presented. Source: SIMAT, SNIES and ICFES, authors' calculation, 2024.

School feeding programmes can contribute to long-term education success

The analysis presented provides strong evidence that school feeding programmes enhance the retention of children, adolescents, and young people within the school system. These findings align with previous research conducted in various contexts. However, we contribute compelling new evidence showing their broader positive impacts, such as improving student learning, increasing high school graduation rates, and enhancing access to tertiary education. Governments and NGOs should therefore intensify their support for these interventions, not only to ensure food security for children globally but also to address the ongoing educational crisis.

References

Anderson, M L, J Gallagher, and E Ramirez Ritchie (2018), “School meal quality and academic performance,” Journal of Public Economics, 168: 81–93.

Bilinski, A, J Poe, J Roth, and P Sant’Anna (2023), “What’s trending in difference-in-differences? A synthesis of the recent econometrics literature,” Journal of Econometrics, 221: 8–24.

Chakraborty, T, and R Jayaraman (2019), “School feeding and learning achievement: Evidence from India's midday meal program,” Journal of Development Economics, 139: 249–265.

Gordanier, J, O Ozturk, B Williams, and C Zhan (2020), “Free lunch for all! The effect of the community eligibility provision on academic outcomes,” Economics of Education Review, 77: [pages not available].

Ruffini, K (2022), “Universal access to free school meals and student achievement: Evidence from the community eligibility provision,” Journal of Human Resources, 57(3): 776–820.

Schwartz, A, and M W Rothbart (2017), “Let them eat lunch: The impact of universal free meals on student performance,” Center for Policy Research Working Papers 203, Center for Policy Research, Maxwell School, Syracuse University.

Wang, D, S Shinde, T Young, and W Fawzi (2021), “Impacts of school feeding on educational and health outcomes of school-age children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Journal of Global Health, 11