Quasi-experimental evidence from Mexico shows that pre-financed, rules-based disaster response can considerably reduce mortality after disasters

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that heavy precipitation events and tropical cyclones are highly likely to increase in frequency and intensity due to climate change (IPCC 2021). The expected increase in extreme weather will be unavoidable because, even in the most favourable scenario, climate change can only be gradually reversed. This inevitability of intensifying extreme weather events increases the urgency of improving the disaster response capacity of governments and multilateral organisations worldwide. This concern is particularly pressing in developing economies, where disaster-related deaths occur at disproportionately higher levels (Kahn 2005, Strömberg 2007).

One area of disaster response with potential for improvement is the institutions used by developing economies to finance and disburse reconstruction resources. As shown by Clarke and Dercon (2016), efforts to provide disaster transfers are often hindered by a lack of pre-financed resources as well as rules and administrative capacity to disburse these resources without delay or leakage. Making matters worse, the largely discretionary nature of fund allocation can result in transfers not being provided in the absence of media coverage and strong democratic institutions (Besley and Burgess 2002, Eisensee and Strömberg 2007).

Mexico's Fonden offers a valuable model for improving disaster response

To improve the provision of disaster transfers, countries and multilateral organisations can redesign disaster response programmes using the same type of plans and rules that insurance companies regularly employ to manage natural disaster risk. A good example of this type of design is Mexico’s Fonden programme, which provides reconstruction resources for public infrastructure and low-income housing. Several features make it possible for Fonden to speed up transfers in the aftermath of a disaster. First, Fonden uses a financial plan that combines a protected budget allocation, excess loss reinsurance, and catastrophe bonds to guarantee the immediate availability of funds. Second, Fonden reduces delays and discretion in transfer allocations by following rules to assess damages and make disbursements.

These rules take advantage of elements of both parametric and indemnity insurance contracts. Like parametric insurance (that covers for the probability of a pre-defined event happening), Fonden generally requires that a municipality (the administrative unit below the state) experience an extreme weather event in excess of a predefined threshold before becoming eligible. Like indemnity insurance (that covers for the damages sustained), Fonden performs damage assessment among eligible municipalities and uses the assessment to set the amount of reconstruction resources. In addition to speed, this institutional design reduces administrative costs and increases protections for taxpayer resources.

Consistent with these potential advantages, my work with Alain de Janvry and Elisabeth Sadoulet (Del Valle et al. 2020) shows that Fonden’s rapid reconstruction accelerates economic recovery by one year and that the value of the economic activity generated by Fonden is as large as its cost. Fonden’s benefits, however, are likely far larger, as rapid reconstruction may also yield non-economic benefits.

New evidence shows Fonden saves lives

In a recent paper (Del Valle 2021), I study whether Fonden can curtail mortality risk from natural disasters. My analysis combines municipal-level measures of the difference in mortality rates before and after disasters with the variation created by Fonden eligibility rules. In particular, I take advantage of Fonden’s heavy rainfall rule, which confers eligibility to municipalities that experience rainfall events above a predefined threshold. Intuitively, because the underlying characteristics of municipalities change smoothly with rainfall, but Fonden eligibility changes discontinuously at the threshold, I can isolate Fonden’s effect on mortality by comparing municipalities that narrowly became eligible to those that narrowly failed.

The paper’s primary outcome is the all-cause annualised mortality rate difference (AMRD). This outcome measures whether a given municipality’s mortality rate after a disaster exceeds its ‘normal’ pre-disaster mortality rate. AMRD values greater than zero indicate that a municipality has experienced excess deaths. Because disasters may precipitate deaths, changing their timing by weeks or months, but not necessarily the number of deaths in the long run, I study the programme’s dynamics by computing the AMRD at various points in time. With AMRD's at four-month intervals over two years, I show that the impact of Fonden peaks at eight months and that the reduction in deaths is largely permanent in the two-year window following a disaster.

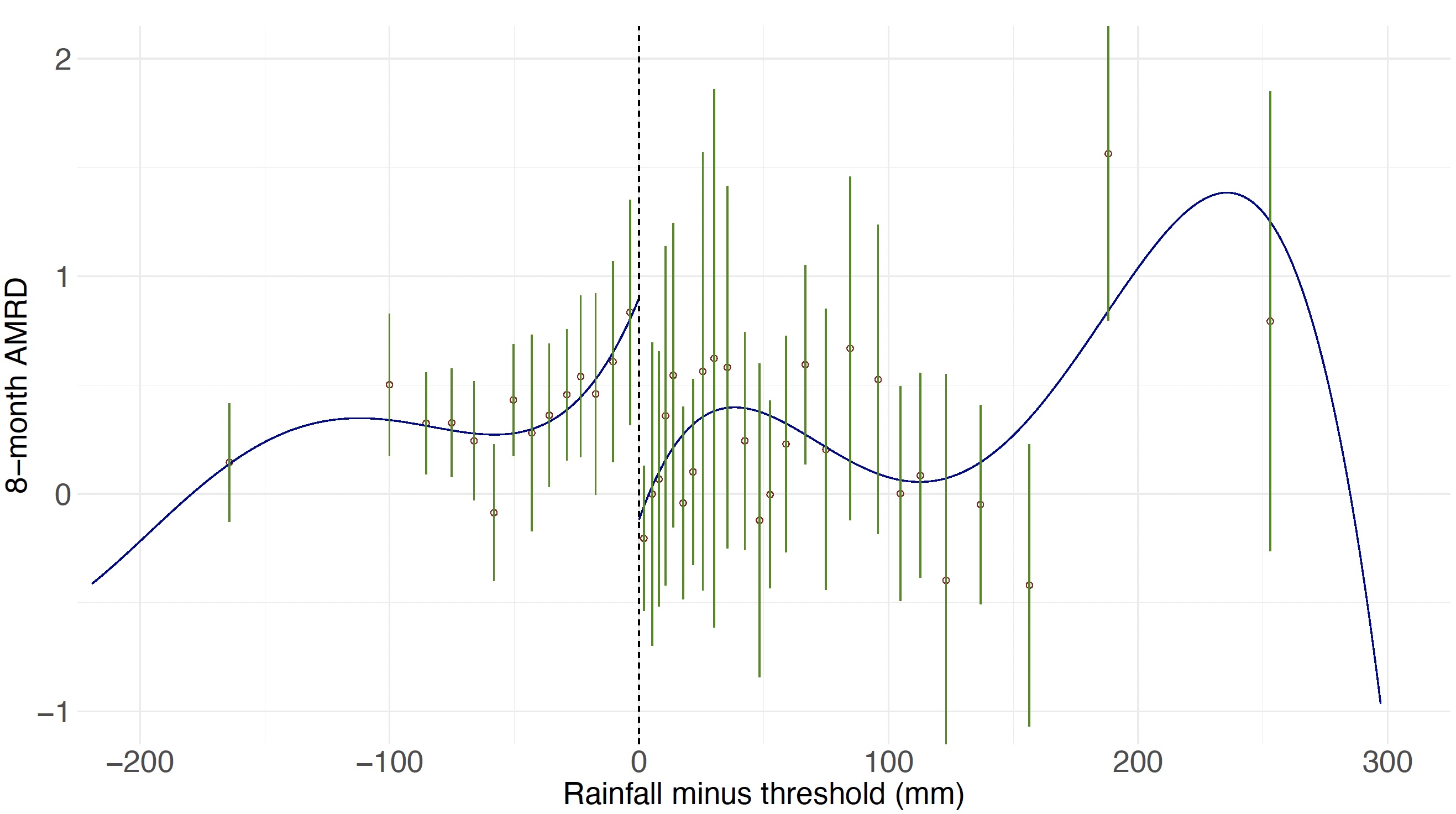

To illustrate this result, Figure 1 plots the eight-month AMRD in relation to rainfall millimetres to the threshold. The figure shows that municipalities immediately to the left of the heavy rainfall threshold (ineligible for Fonden) report an increase of 0.79 excess deaths per 1,000 person-years. By comparison, municipalities immediately to the right of the threshold (eligible) experience no excess deaths. Estimates of the impact of Fonden for various periods indicate that the programme fully mitigates excess deaths eight months after a disaster and up to 75% of excess deaths two years after a disaster.

Figure 1 Municipalities eligible for Fonden (right of threshold) experience reduced excess mortality after a disaster

Note: The variable rainfall (in millimetres) to the threshold is partitioned into bins of roughly the same number of observations. The circles plot the mean for each bin. The error bars plot the 95% confidence intervals for the means. The solid lines plot a polynomial fit for each side of the threshold.

How does rapid reconstruction save lives?

Three pieces of evidence indicate that Fonden saves lives by accelerating the restoration of the infrastructure necessary to provide health services:

- First, I find that the Fonden-led reduction in mortality is driven by conditions responsive to basic medical care (amenable)

- Second, I show that Fonden’s effect is further concentrated in municipalities where amenable deaths were likely averted before a disaster because health services were generally available

- Third, I find that adults aged 50 or older (who have a higher prevalence of amenable conditions) benefit disproportionately from Fonden.

How many lives are saved, and at what cost?

A back-of-the-envelope calculation based on the estimates for adults 50 or older indicates that Fonden saves 18,107 lives per year at an average cost of $43,373 (constant 2010 international dollars). Given that the most conservative estimate for the value of statistical life in Mexico is $210,880 (de Lima 2020), Fonden’s benefit-cost ratio for saving lives is at least 4.9.

Fonden’s cost of saving a life also compares favourably relative to other disaster preparedness interventions. For example, the interventions reviewed by Tengs et al. (1995) have a median cost per life saved three orders of magnitude greater than the cost of Fonden.

Further improving the provision of reconstruction resources

While Fonden offers a marked improvement over the standard disaster response model, the design can be further refined. One limitation of the programme and other parametric insurance contracts in general is that the indices used for verification are imperfectly correlated with damages. This imperfection meant for Fonden that some of the ineligible municipalities experienced damage but received no reconstruction funding. The literature on agricultural index insurance provides several paths forward (Carter et al. 2017). The paths range from improving correlation by increasing the density of weather stations or using information from remote sensing platforms to improving contract design by allowing an appeal process that uses an audit rule or a secondary index to determine eligibility. Another opportunity for improvement that Fonden’s rules gradually gravitated towards is the idea that further risk reduction can be achieved by permitting reconstruction resources to be used to harden and reallocate infrastructure to lower-risk areas.

Redesigning disaster transfers moving forward

While the literature on the impact of pre-financed rules-based disaster response is still in its infancy, recent work in Bangladesh by Gros et al. (2020) shows that United Nations cash transfers, allocated with a predicted flood index, considerably reduced household vulnerability to flooding. These findings and those of Fonden suggest that the pre-financed rules-based disaster response offers a valuable model for countries and multilateral organisations to improve the provision of disaster aid.

References

Besley, T and R Burgess (2002), “The political economy of government responsiveness: Theory and evidence from India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(4): 1415–1451.

Carter, M, A de Janvry, E Sadoulet and A Sarris (2017), “Index Insurance for Developing Country Agriculture: A Reassessment”, Annual Review of Resource Economics 9: 421–38.

Clarke, D J and S Dercon (2016), Dull Disasters? How planning ahead will make a difference, New York: Oxford University Press.

De Lima, M (2020), “The value of a statistical life in Mexico”, Journal of Environmental Economics and Policy 9(2): 140–166.

Del Valle, A, A de Janvry and E Sadoulet (2020), “Rules for Recovery: Impact of Indexed Disaster Funds on Shock Coping in Mexico”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12(4): 164–95.

Del Valle, A (2021), “Saving lives with pre-financed rules-based disaster aid: Evidence from Mexico”, MedRxiv.

Eisensee, T and D Strömberg (2007), “News droughts, news floods, and US disaster relief”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(2): 693–728.

Gros, C, M Bailey, S Schwager, A Hassan, R Zingg, M M Uddin, M Shahjahan, H Islam, S Lux and C Jaime (2019), “Household-level effects of providing forecast-based cash in anticipation of extreme weather events: Quasi-experimental evidence from humanitarian interventions in the 2017 floods in Bangladesh”, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 41: 101275.

IPCC (2021), "Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate", in: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kahn, M E (2005), “The death toll from natural disasters: the role of income, geography, and institutions”, Review of Economics and Statistics 87(2): 271–284.

Strömberg, D (2007), “Natural disasters, economic development, and humanitarian aid”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 21(3): 199–222.

Tengs, T O, M E Adams, J S Pliskin, D G Safran, J E Siegel, M C Weinstein and J D Graham (1995), “Five-hundred life-saving interventions and their cost-effectiveness”, Risk Analysis 15(3): 369– 390.