National air and water quality benefit from strong financial, judicial, and labour market institutions, through comparative advantage. Improving national institutions attracts clean industries but reshuffles dirty production to other countries.

Environmental quality differs enormously around the world. For example, air pollution in Pakistani cities frequently violates global health standards, while air pollution in Swiss cities rarely does. These differences have large stakes—the World Health Organization (2021) estimates that outdoor air pollution causes four million premature deaths annually, 90% of them in low- and middle-income countries.

Why does environmental quality differ across the world?

Economists have proposed several explanations for these differences in environmental quality. One theory, the Pollution Haven Hypothesis (Russell and Landsberg 1971), emphasises that some countries have strict environmental regulation, while others have weak environmental regulation. Weak environmental regulations attract polluting industries and give them little incentive to invest in pollution control technologies.

A related explanation, the Environmental Kuznets Curve (Grossman and Krueger 1995), proposes that pollution first increases with income per capita as a country grows, but later decreases with income per capita as a country continues growing past some turning point. This inverted-U shaped relationship between pollution and income per capita could reflect the idea that after a certain essential income level, additional income lets societies demand better environmental quality. This inverted U could also reflect the development process wherein economies transition from agriculture to manufacturing (which increases pollution) and then to services (which decreases pollution).

My new research (Shapiro 2024) proposes an additional explanation for the vast differences in environmental quality around the world: strong financial, judicial, and labour market institutions make clean industries more productive, and so strong institutions attract clean industries and displace dirty industries. I find that institutions play an underappreciated role in explaining global patterns of environmental quality.

Why do clean industries need strong financial institutions?

To understand why clean industries need strong financial institutions, consider two types of assets, tangible and intangible. In some industries, most assets are physical and tangible, such as boilers and machines. In other industries, most assets are intangible, such as brand equity. An industry can use tangible assets as collateral, which helps the industry obtain external financing. If a firm with tangible assets goes bankrupt, lenders can sell the assets to help recoup their investment. Industries with tangible assets therefore rely relatively less on financial institutions to grow since they can use assets as collateral, while industries with intangible assets depend relatively more on a strong financial sector. The dirtiest industries have among the highest reliance on tangible assets, which makes dirty industries depend relatively little on financial institutions. Dirty industries need tangible assets because dirty industries convert dense, heavy raw materials into finished products. Intangible assets like brand equity are more important to relatively clean industries.

Cleaner industries need more specialised contracts that are supported by strong judicial institutions

Clean industries also disproportionately rely on judicial institutions, while dirty industries do less so. Dirty industries predominantly use raw materials like iron and lead as inputs, which are relatively homogeneous. These inputs are less often exchanged through specialised contracts that depend on judicial institutions to be enforced and are more often commodities traded through open markets like the Chicago Mercantile Board of Exchange. Such homogeneous goods rarely require specialised bilateral contracts to exchange, and thus depend less on judges to enforce complex contracts. By contrast, the more complex inputs used to produce cleaner goods more often rely on bilateral contracts, which require strong judicial institutions to enforce.

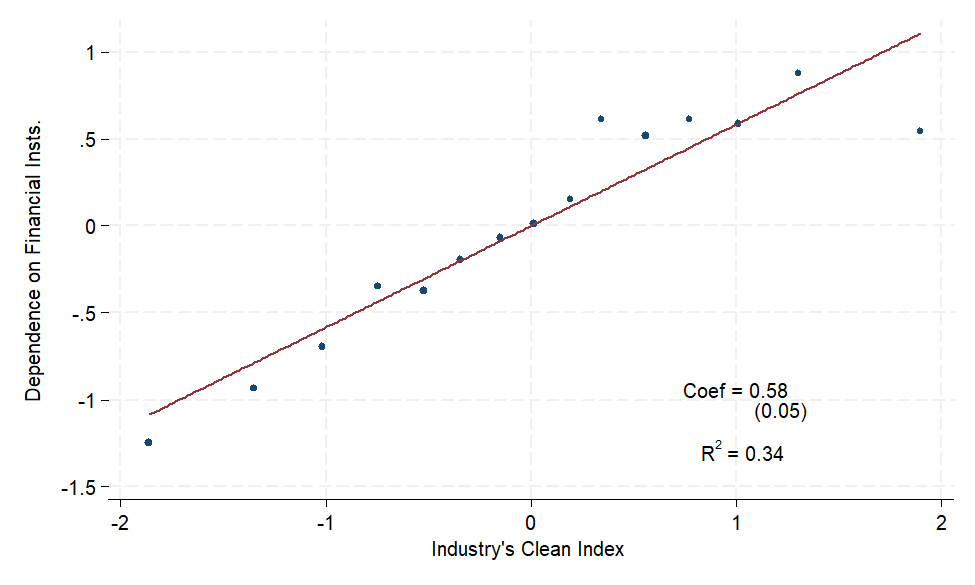

Motivated by these examples, I find several pieces of evidence showing that strong institutions attract clean industries and improve environmental quality. Firstly, countries with strong financial and judicial institutions have better air and water quality. Secondly, I find that cleaner industries depend systematically more on all three types of institution (financial, judicial and labour market). By measuring how clean an industry is by its air and water pollution emissions per dollar of output and its dependence on financial institutions by the share of an industry’s assets that are tangible, we can observe such a pattern. Figure 1 shows that cleaner industries depend more on financial institutions. I find similar patterns for judicial and, to a lesser extent, labour market institutions.

Figure 1: Clean industries need strong financial institutions because clean industries have intangible assets

How do these forces affect patterns of production and international trade?

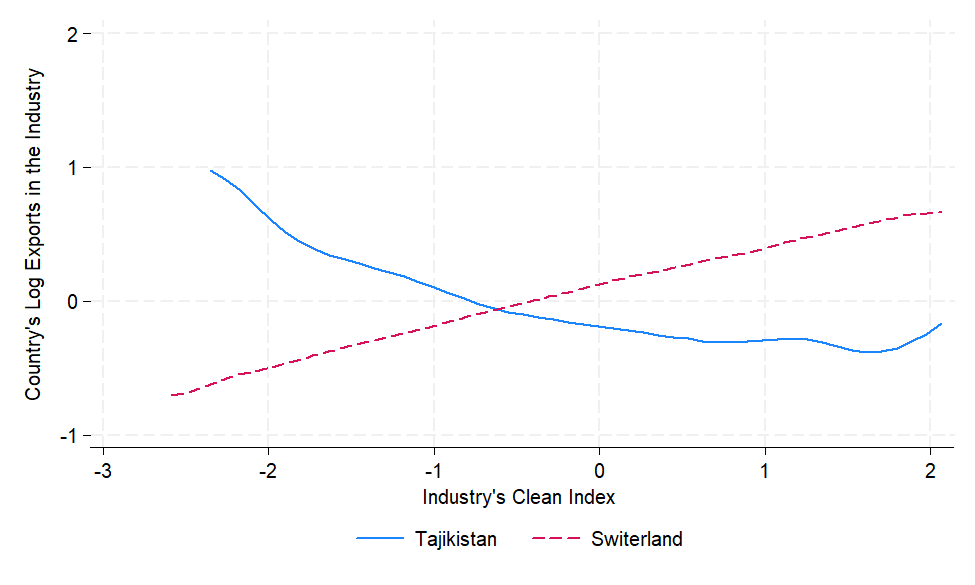

Countries with stronger institutions specialise in exporting cleaner goods. Figure 2 below shows that Tajikistan, with weak institutions, specialises its exports in dirty goods. Switzerland, with strong institutions, specialises its exports in clean goods. This two-country comparison extrapolates well to all countries with above-median versus below-median institutional quality.

Statistical analyses adjusting for the stringency of countries’ environmental policies, tariff rates, and numerous other variables also find that the strength of a country’s institutions drive its specialisation in clean industries. This pattern even persists when looking at changes in a country’s institutions over time, when using historical natural experiments that vary institutions, and when looking at differences in institutions across states within India.

Figure 2: Switzerland, with strong institutions, exports clean goods; Tajikistan, with weak institutions, exports dirty goods

Clean industries depend on institutions because cleaner industries have processed, complex inputs. For example, clean industries have lower cost shares of energy and raw materials, which make them pollute less, but also make them depend more on financial and judicial institutions.

Mechanisms that explain the differences in countries’ environmental quality

I then examine what can better account for international differences in environmental quality: differences in the composition of production across industries (i.e. what share of output each industry accounts for in an economy) or differences in the pollution intensity of a given industry (i.e. production techniques). I find that composition plays at least as large a role as production techniques in explaining international differences in pollution.

Strengthening institutions reshuffles dirty production abroad

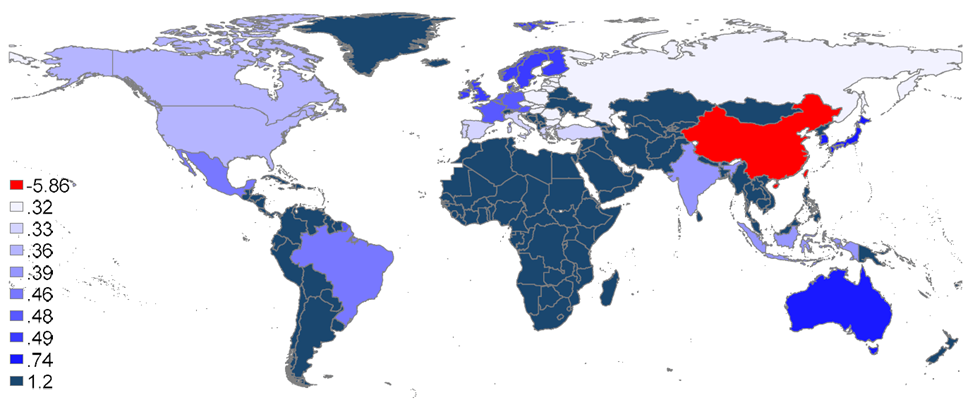

Finally, I use a model of trade, production, and pollution to study how changes in one country’s institutions affect environmental quality through comparative advantage. I find that improving the quality of a country’s institutions substantially improves that country’s environmental quality, though worsens environmental quality in other countries. For example, Figure 3 below shows that improving the quality of institutions in China by one standard deviation would decrease Chinese pollution emissions by 6%, but would increase pollution in all other countries, especially nearby trading partners like Central and Southeast Asia. Comparative advantage accounts for this international reshuffling of production. As one country’s institutions improve, the country attracts clean production from around the world, though reshuffles dirty production to its trading partners, where environmental quality suffers.

Figure 3: Improving China’s institutions by one standard deviation decreases pollution in China by 6% but increases emissions elsewhere

Institutions matter for environmental quality

The 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics recognised the study of how institutions affect economic growth (Acemoglu et al. 2001, 2002). This summary highlights a different and underappreciated consequence of institutions—they benefit domestic environmental quality by attracting clean industries. Because low-income countries have relatively weak institutions, these results also help explain why low-income countries experience high pollution levels. At the same time, strengthening institutions reshuffles dirty production abroad; stronger institutions in one country worsen foreign environmental quality.

References

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson, and J A Robinson (2001), “The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation,” American Economic Review, 91(5): 1369–1401.

Acemoglu, D, S Johnson, and J A Robinson (2002), “Reversal of fortune: Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4): 1231–1294.

Grossman, G M, and A B Krueger (1995), “Economic growth and the environment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(2): 353–377.

Russell, C S, and H H Landsberg (1971), “International environmental problems—a taxonomy,” Science, 172(3990): 1307–1314.

Shapiro, J S (2024), “Institutions, comparative advantage, and the environment.”

World Health Organization (2021), “Ambient air pollution attributable deaths.”