Increasing women’s use of a digital financial service in Tanzania, mobile money, empowered women and led to improvements in women’s control over their finances.

Women’s empowerment is an important outcome, both in its own right and as a channel to improving other development outcomes, such as children’s health and education (Doepke and Tertilt 2019, Duflo 2012). While many programmes have aimed to raise women’s empowerment by increasing women’s income or resources, it is control over resources that ultimately determines women’s status in the household (Anderson and Eswaran 2009).

Digital financial services and women’s empowerment

The increased availability of digital financial services offers a promising avenue for increasing women’s control over their resources by providing women with a secure, private place in their own name to store money. However, large gender gaps in the adoption and use of digital financial services limit this potential, with women less likely to use popular services like mobile money, use them less often, for fewer types of and smaller value transactions (Demirgüç-Kunt 2021).

In our research (Heath and Riley 2024), we conduct a field experiment in Tanzania to study whether increasing women’s use of mobile money services can increase their control over financial resources and raise their empowerment. We encourage women’s use of mobile money services by randomly assigning female microfinance borrowers to switch their weekly loan repayments from cash to mobile money. We study the effects of this switch on women’s wider use of mobile money services, their financial control and their empowerment after 10 months.

Mobile money use in Tanzania

Mobile money services are widely used in Tanzania, with 50% of the population owning a mobile money account in 2021 (Demirgüç-Kunt 2021). However, despite these high rates of uptake and the rapid growth of mobile money services, use of mobile money for transactions beyond remittances remains uncommon, particularly among women. While 50% of men report saving with mobile money, only 27% of women do. Only 4% of men and 1% of women reported making digital merchant payments (Demirgüç-Kunt 2021). This suggests there is potential for benefits from closing gender gaps and increasing women’s use of these services.

The intervention: Weekly loan repayments for female microfinance clients using mobile money

We conducted our study with female microfinance clients in the Mwanza region of Tanzania. All women have a loan for a business that they own and operate. Women obtain a loan by joining a group of 10-30 women in their community. In the status quo, repayments are made weekly in cash at the group meeting.

We worked with 152 microfinance groups containing nearly 3,500 women in this study. Microfinance groups were randomly allocated to either remain with the status quote of cash loan repayment (control - 51 groups) or to switch to repayment of the loan using mobile money (treatment - 101 groups). Repaying with mobile money was encouraged but not compulsory in the treatment groups, with treated women making an average of 8 out of 25 loan repayments using mobile money. Nothing else about the loan disbursement or collection process was changed, and women in the treatment arm still attended the group meeting in person to show proof of the mobile money transfer to the loan officer.

Greater use of mobile money, higher financial control and increased empowerment

We find that, after 10 months, women who made their loan repayments using mobile money use mobile money services substantially more for all kinds of transaction:

- Treated women are 50% more likely to allow customers to pay for purchases using mobile money

- Treated women are 30% more likely to have used mobile money in the past week

- The value of their transactions using mobile money is 36 USD PPP a month higher, 30% higher than in the control group.

- Treated women are 6 percentage points more likely to save with mobile money and have 16 USD PPP more saved on their mobile money account, more than double the mean control group saving on mobile money of 12 USD PPP.

This increase in use is accompanied by an increase in comfort using mobile money and increased likelihood that the woman makes mobile money transactions by herself.

Did this increased use of mobile money services translate into higher financial control?

We find that treated women are more likely to report deciding how to spend their own income, report less pressure to share money with their spouse and are more likely to discuss their income with their spouse. They are also less willing in an incentivised task to give up money for the household in order to control it themselves, consistent with greater financial control (Almas et al. 2018, Jayachandran et al. 2023). Overall, this suggests that treated women feel more in control of their money, and hence are more comfortable discussing it with their spouse and less willing to pay to control additional money. This highlights that increased use of digital financial services can meaningfully increase women's financial control and mitigate sharing pressure.

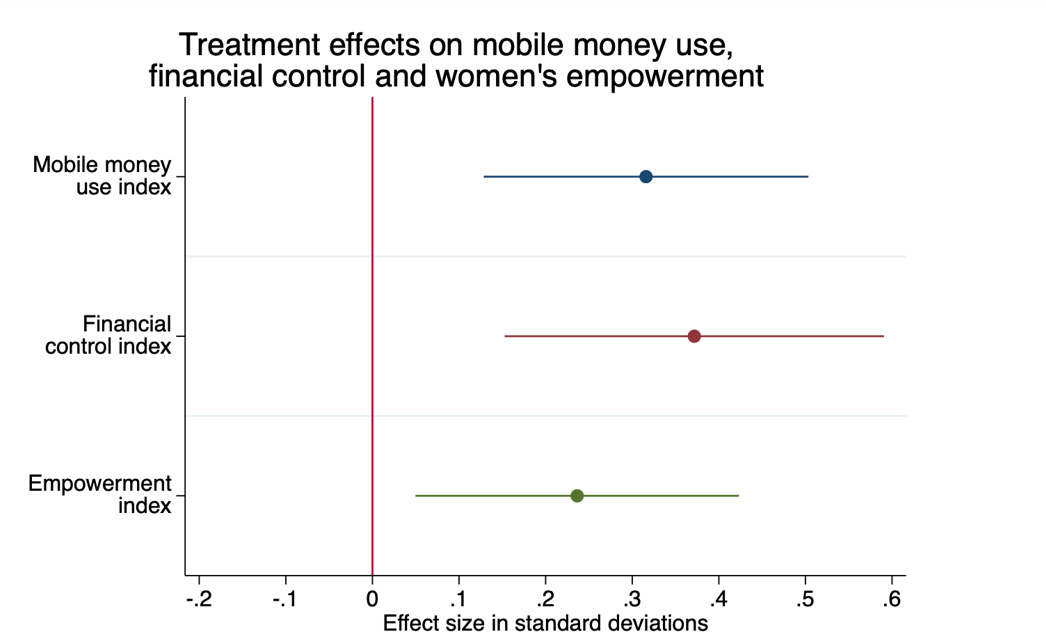

Women’s empowerment increases substantially as a result of the treatment. Treated women have more input into household decision making, particularly on food and clothing expenditures, and have more involvement in financial decision making in general. Consistent with this reported increase in decision making, we see that the allocation of expenditures shifts towards women’s and children’s goods in the households of treated women (Bobonis 2009). Increases in empowerment are greatest for treated women with the lowest levels of empowerment before the start of the intervention. This provides strong evidence that increasing women’s use of mobile money services increases their empowerment in the household. Figure 1 shows these results graphically for standardised indices of the outcomes discussed.

Figure 1: Treatment increased use of mobile money, financial control and women’s empowerment.

We find no effects of treatment on women’s business outcomes. This is likely because baseline use of mobile money for payments is very low in this context, and a market level intervention would be required to change use by both customers and businesses simultaneously (Higgins forthcoming). We also do not see evidence that women are saving on the mobile money account in order to make investments into their businesses, perhaps because meaningful business investments require larger savings than the women are able, or willing, to accumulate. This is consistent with Riley (2024), who studied the disbursement of microfinance loans with mobile money, and found that while digital disbursement increased investment of the loan into the business compared to cash disbursement, the mobile money accounts did not continue to be used for business reinvestment and growth.

The social consequences of empowering women in Tanzania

Reassuringly, there is no evidence of backlash against women as a result of their increased financial control and empowerment. There are no changes in discord with the spouse or changes in spouse or other household member incomes in the households of treated women (Bernhardt et al. 2019).

We see some evidence that social interaction between group members within the treated groups increased. This is likely due to more time being available for social interaction when the need to count cash was removed, with group meetings also taking 10 minutes less on average. This suggests that the benefits in terms of women’s empowerment from the digitisation of microfinance loans does not have to come at the expense of social cohesion (Harigaya 2016), which prior literature has highlighted as an important element of microfinance group’s success (Feigenberg et al. 2013). In line with this, we find no changes in women’s loan repayment outcomes in treated groups.

Policy implications: Encourage the digitisation of payments

Our findings highlight an important role for policymakers and organizations who, through integrating digital financial services into other financial products, can increase women’s experience and use of them, improving women’s outcomes.

References

Almas, I, A Armand, O Attanasio, and P Carneiro (2018), "Measuring and Changing Control: Women’s Empowerment and Targeted Transfers," Economic Journal, 128(612): F609–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12517.

Anderson, S, and M Eswaran (2009), "What Determines Female Autonomy? Evidence from Bangladesh," Journal of Development Economics, 90(2): 179–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.10.004.

Bernhardt, A, E Field, R Pande, and N Rigol (2019), "Household Matters: Revisiting the Returns to Capital among Female Microentrepreneurs," AER: Insights, 2(2): 141–60. https://doi.org/10.1257/aeri.20180444.

Bobonis, G J (2009), "Is the Allocation of Resources within the Household Efficient? New Evidence from a Randomized Experiment," Journal of Political Economy, 117(3): 453–503.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A, L Klapper, D Singer, and S Ansar (2022), "The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19," The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1897-4.

Doepke, M, and M Tertilt (2011), "Does Female Empowerment Promote Economic Development?" CEPR Discussion Paper No DP8441: 48. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-5714.

Duflo, E (2012), "Women Empowerment and Economic Development," Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4): 1051–79. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.4.1051.

Feigenberg, B, E Field, and R Pande (2013), "The Economic Returns to Social Interaction: Experimental Evidence from Microfinance," The Review of Economic Studies, 80(4): 1459–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdt016.

Harigaya, T (2016), "Effects of Digitization on Financial Behaviors: Experimental Evidence from the Philippines."

Heath, R, and E Riley (2024), "Digital Financial Services and Women’s Empowerment: Experimental Evidence from Tanzania." https://drive.google.com/file/d/1CcpAdDk5-dHvjGZyASnurZi970IjwRMa/view

Higgins, S (Forthcoming), "Financial Technology Adoption: Network Externalities of Cashless Payments in Mexico," American Economic Review.

Jayachandran, S, M Biradavolu, and J Cooper (2023), "Using Machine Learning and Qualitative Interviews to Design a Five-Question Survey Module for Women’s Agency," World Development, 161: 106076. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106076.

Riley, E (2024), "Resisting Social Pressure in the Household Using Mobile Money: Experimental Evidence on Microenterprise Investment in Uganda," American Economic Review, 114(5): 1415–47. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20220717.