Having the option of getting paid later can help developing-country workers save for larger purchases, and make lasting improvements to their homes

Many people in developing countries face barriers to saving. Market frictions hinder the supply of formal financial products, and nearly half of adults in developing countries do not have access to an account at a bank or another formal financial institution (Demirgüc-Kunt et al. 2015). In addition, the ability to save can be hampered by demand-side constraints such as impatience or social pressure to share income (Ashraf et al. 2006, Jakiela and Ozier 2016). In the absence of affordable credit, constraints on saving can mean that people struggle to access sufficient funds for making basic investments such as upgrading their dwellings with iron sheet roofs, paying for school fees, or having better food options during times of lower income.

A simple method for saving up larger sums is to defer receipt of income, a type of commitment device that is surprisingly popular in developing countries. Employees sometimes ask their employers to hold on to wages they are owed until a later date. In Kenya, for example, dairy farmers are willing to accept lower prices for their milk to receive some of their sales as monthly rather than as daily payments (Casaburi and Macchiavello 2015).

Such deferral of payments keeps transaction costs low, and regular, automatic deductions make it easy for savers to follow through on their financial and life plans. This convenience is important since the benefits of any single deposit can easily be outweighed by small transportation, opportunity, or attention costs that prevent the formation of savings. Thanks to digitisation and ongoing financial innovations, automatic deferral of income and options to customise payment streams are now more possible than ever and can be leveraged to help people overcome barriers to save.

Pay Me Later: A simple employer-based savings scheme

In a recent randomised controlled trial at a tea company in Malawi, we turned the idea of deferring payments into a practical savings product for the firm’s employees (Brune, Chyn, and Kerwin forthcoming). The workers that took part in the programme normally received their wages every two weeks in cash, and few were making use of the limited available formal savings options. To test whether deferred payment could be an effective savings device, our study randomly provided workers with the option to have a fraction of their pay withheld each payday and paid out in a lump sum at the end of the season. Workers were able to drop out of the scheme to receive their accumulated funds, without penalty, by visiting the firm’s administrative offices to fill out early-exit paperwork.

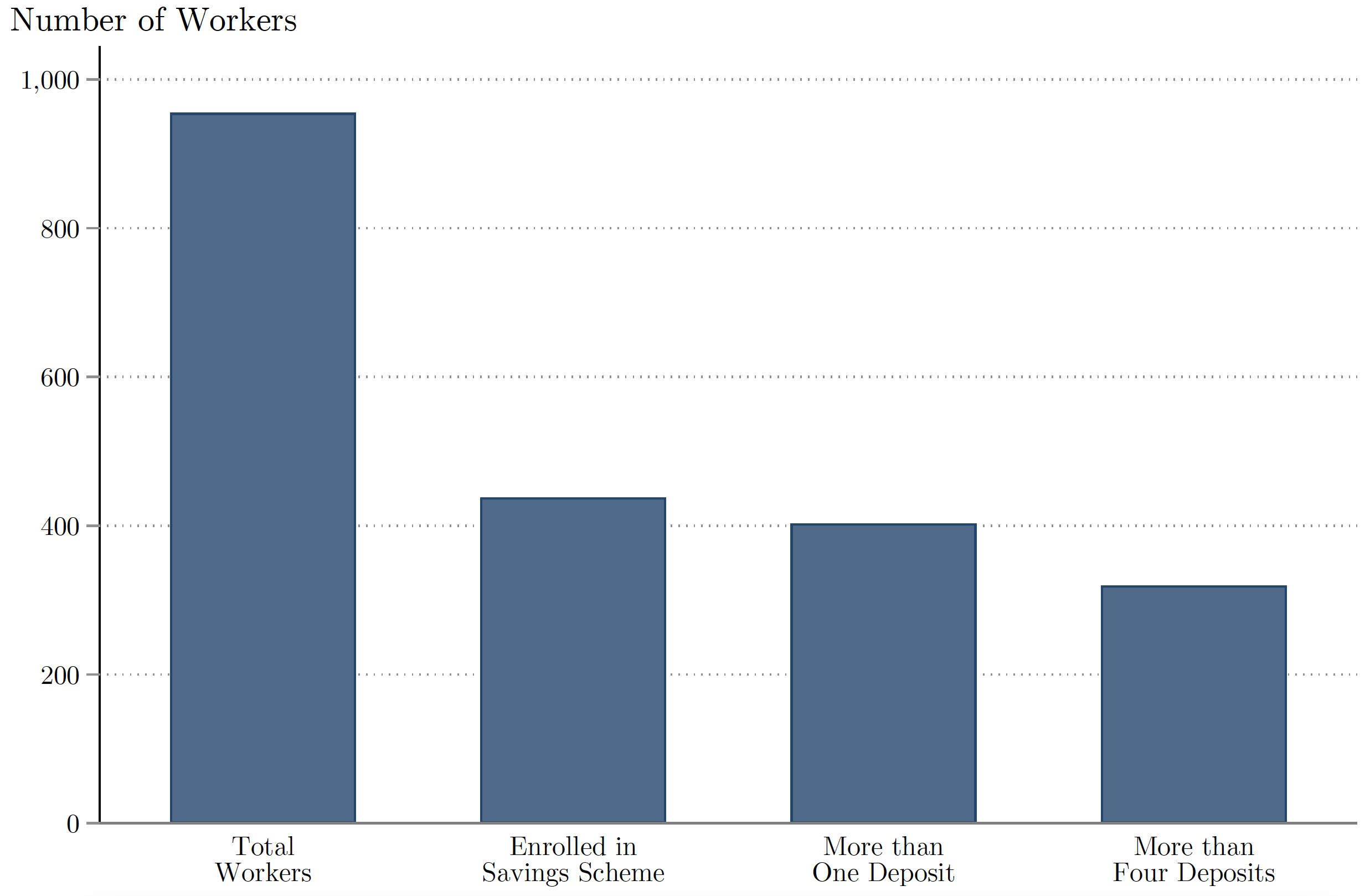

Our study produced three key findings. First, we found that the product was popular and improved worker productivity during the season. About half of workers were interested in participating in the deferred payment savings scheme; those who signed up used it very actively, with 73% of all workers who enrolled in the scheme making at least five deposits (Figure 1). The set of workers in the treatment group who participated in the scheme saved 14% of their income through the program. During the season, we also found that these treated workers had 4% higher productivity relative to the control group of workers who did not have access to the savings scheme. These results are in line with the idea that barriers to saving may also depress labour supply (Callen et al. 2019). One reason for this is that working harder to earn more becomes less appealing if one’s income stream cannot be easily aggregated to pay for goods and services that people value.

Figure 1 Take-up and utilisation of the savings scheme by the treatment group

Note: This figure reports the totals for the overall number of workers in the treatment group, the total number who enrolled, and the total number that made more than one or more than four deposits.

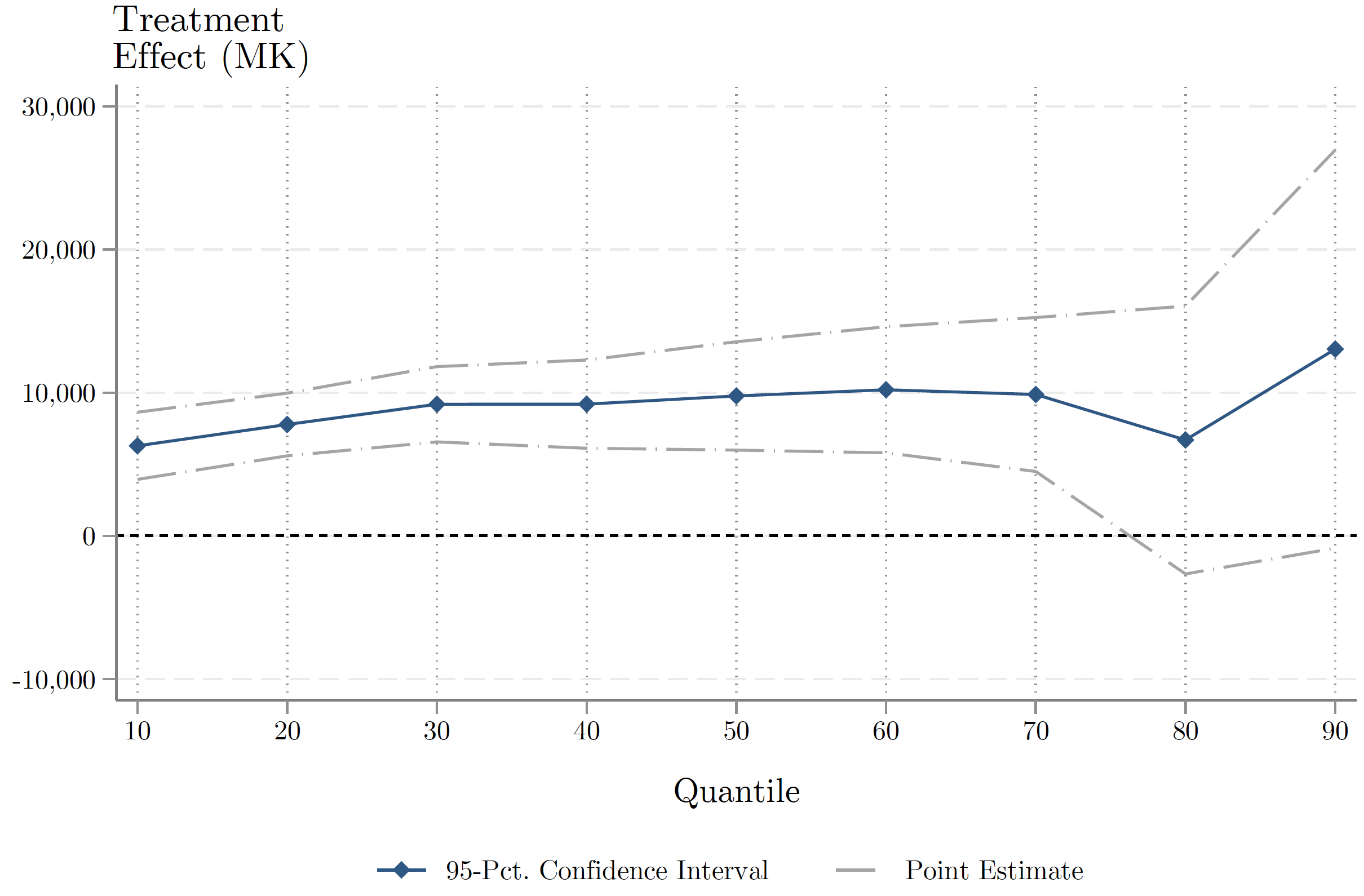

Second, the deferred wages scheme was effective. Workers treated with the scheme increased their net savings by 23% by the end of the savings period, and the increases occurred throughout the distribution of savings (Figure 2). After receiving their deferred pay, they spent a large fraction of their savings on durable goods – especially on products they had mentioned as savings goals, such as goods for home improvements. Overall, the value of their durable assets increased by 10%, and participants had more iron sheets that could be used to improve the roofs of their homes.

Figure 2 Quantile treatment effects on savings

Note: This figure plots estimated treatment effects by percentile of the outcome variable. See Brune et al. (forthcoming) for further details of this analysis.

Third, saving through the deferred wage scheme had lasting effects. Over the following year, we let treatment-group workers participate in the savings product two more times and followed-up nine months after the lump sum payout for the last round. At the end of a nearly two-year period, we found that workers in the deferred wages scheme had made significant improvements to their housing: the treatment group was 10% more likely to have upgraded the roofs on their homes to metal, rather than less-durable materials such as thatched grass.

How were workers able to save more?

The Pay Me Later scheme was unusually popular and successful for a savings intervention. Studies of other financial products have often shown low take-up or utilisation (Dupas et al. 2018) and rarely have effects on important outcomes later on (see Dupas and Robinson 2013 and Schaner 2018 for two examples of notable exceptions).

What made this product work so well? We ran a set of additional choice experiments to figure out which features drove the high demand for this form of savings.

One key feature is paying out the savings in a lump sum. When we offered a version of the scheme that paid out the savings smoothly (in six weekly instalments after the end of the season), take-up fell by 35%. Another important feature is the automatic ‘deposits’ that are built into the design. We offered some workers an identical product that differed only in that deposits were manual – a project staffer was located adjacent to the payroll site to accept deposits. Sign-up for this manual deposits version matched the original scheme, but actual utilisation was much lower. Additional analysis of participants’ self-reported ability to reign in impulse spending suggests that automatic deposits are beneficial in part because they help workers overcome self-control problems.

On the other hand, the seasonal timing of the product was much less important for driving demand: it was just about as popular during the offseason as the main harvest season. Relaxing the commitment savings aspect of the product also does not matter much. When we offered a version of the product where workers could access the funds at any time during the season, it was just as popular as the original version where the funds were locked away.

Policy implications for boosting savings

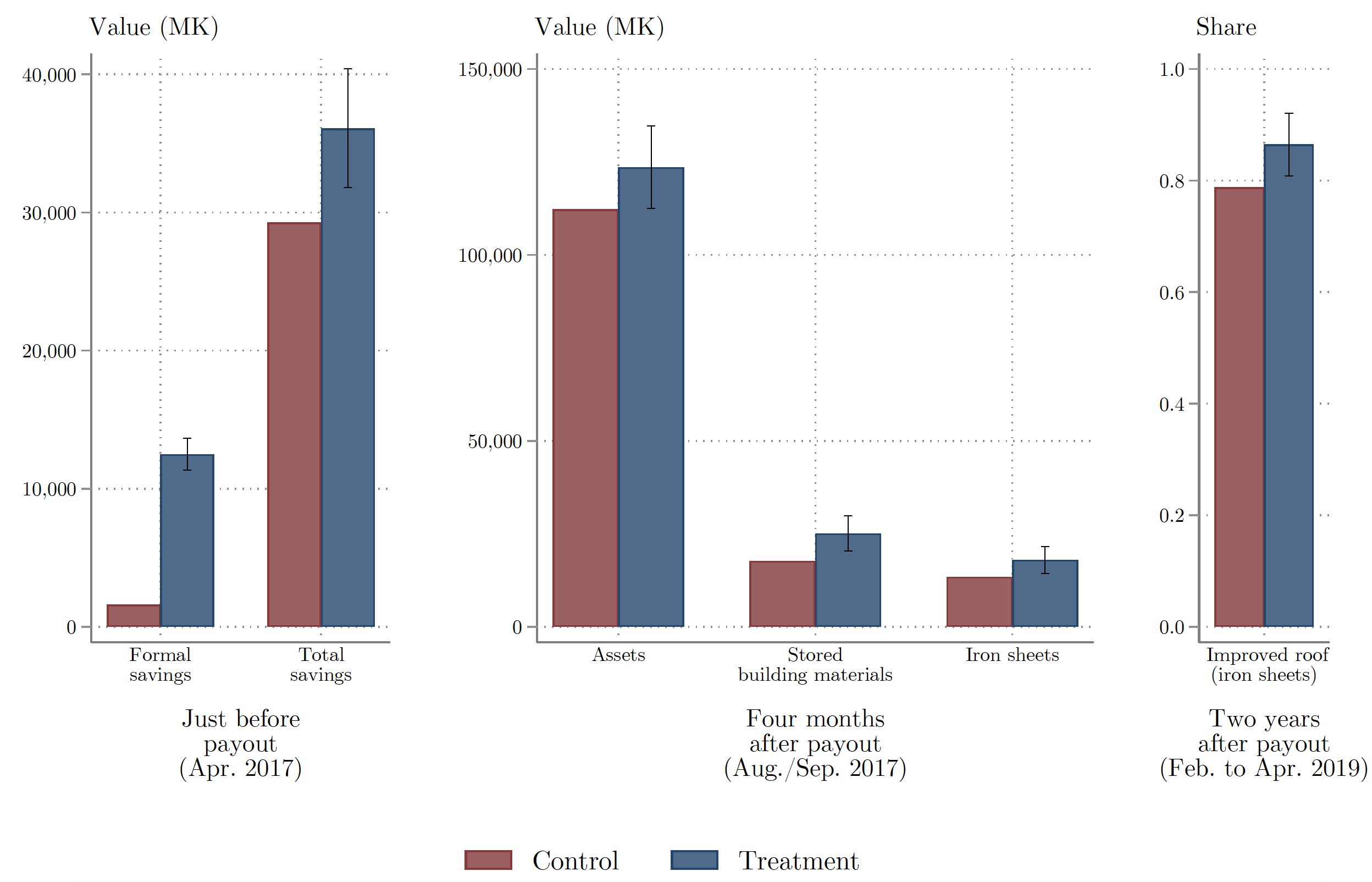

In summary, letting people opt in to get paid later is a promising way to make saving easier. It can be run at nearly zero marginal cost once the payroll system is designed to accommodate it. As shown in Figure 3, our research also demonstrates that the benefits of this type of savings can be substantial. Deferring pay has impacts on formal and net savings while the scheme is in place, and there are positive effects on asset purchases after payout. We find that workers in the programme were more likely to have made durable investments in their homes two years after the initial round of the scheme.

Figure 3 Comparison of control and treatment groups on key outcomes

Note: This figure summarises the impact of the deferred payment scheme on our main outcomes. The maroon (left) bar for each outcome displays the average for workers in the control group. The navy (right) bar displays the estimated average outcome for the treatment group. The whiskers show the 95% confidence interval for the difference between the two groups.

Since modern payroll and payment software can easily manage customised payment streams, similar ideas could potentially be deployed not just by firms but also by governments running cash transfer programmes and workfare schemes, or by providers of mobile money-based financial products. Furthermore, in the context of mobile money, providers could add features that allow customers to set up automatic deductions into separate, less-accessible accounts with lump sum release of funds, thereby making it easier for people to follow through on their savings plans.

References

Ashraf, N, D Karlan, and W Yin (2006), “Tying Odysseus to the mast: Evidence from a commitment savings product in the Philippines”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 121(2): 635–672.

Brune, L, E Chyn, and J T Kerwin (Forthcoming), “Pay Me Later: Savings Constraints And the Demand for Deferred Payments”, American Economic Review.

Callen, M, S de Mel, C McIntosh, and C Woodruff (2019), “What Are the Headwaters of Formal Savings? Experimental Evidence from Sri Lanka", Review of Economic Studies 86(6): 2491-2529.

Casaburi, L and R Macchiavello (2019), “Demand and Supply of Infrequent Payments as a Commitment Device: Evidence from Kenya", American Economic Review 109(2): 523-555.

Demirgüc-Kunt, A, L F Klapper, D Singer, and P Van Oudheusden (2015), “The Global Findex Database 2014: Measuring Financial Inclusion Around the World", Social Science Research Network Scholarly Paper 2594973.

Dupas, P, D Karlan, J Robinson, and D Ubfal (2018), “Banking the Unbanked? Evidence from Three Countries", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10(2): 257-297.

Dupas, P and J Robinson (2013), “Savings Constraints and Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Kenya", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5(1): 163-192.

Jakiela, P and O Ozier (2016), “Does Africa Need a Rotten Kin Theorem? Experimental Evidence from Village Economies”, Review of Economic Studies 83(1): 231–268.

Schaner, S (2018), “The Persistent Power of Behavioral Change: Long-Run Impacts of Temporary Savings Subsidies for the Poor", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10(3): 67-100.