Legal constraints to firm growth incentivise large firms to find loopholes by hiring contract labour

In the late 1940s, the new Indian nation, fearful of job losses if large British companies were to leave India, passed a law that made it illegal for large companies to downsize. This law, which became known as the Industrial Disputes Act (IDA), was likely successful in ameliorating the immediate crisis in the late 1940s, but it also likely distorted incentives for Indian entrepreneurs. After all, who would want to invest if one was stuck paying workers that are no longer needed if the investment turned out to be unsuccessful?

Growth constraints for Indian firms

There is considerable evidence that the IDA did in fact have this powerful disincentive effect. The Indian manufacturing sector predominately comprises of a large number of informal firms, with only a small number of large firms that have a high marginal product of labour. While US manufacturing firms typically grow by a factor of eight over three decades, the typical manufacturing firm in India does not grow at all over its life cycle (Hsieh et al. 2014a, Hsieh et al. 2014b). These facts suggest that laws like the IDA discourage Indian entrepreneurs from growing, and as a result there are few large productive firms and too many small, unproductive firms.

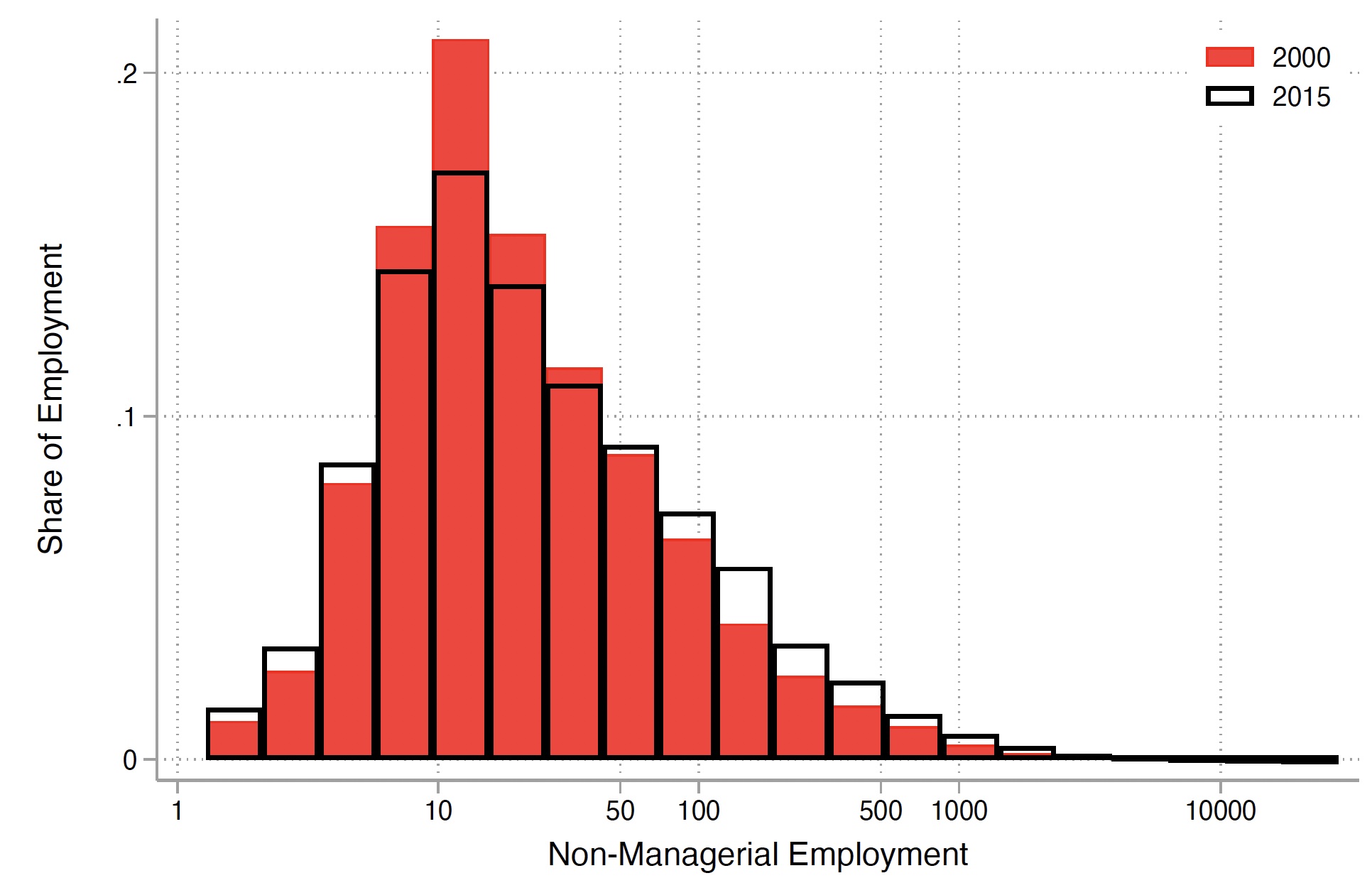

However, the constraints on large firms appeared to have diminished since the early 2000s despite the fact that there has been no change in the IDA. The reforms that started in 1991 mostly dismantled the reservations for small-scale industries and the industrial licensing laws, but left the IDA untouched. Consider the evidence in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows that the thickness of the right tail of formal Indian manufacturing increased between 2000 and 2015. Figure 2 shows that average value added per worker is increasing in firm employment in 2000 and 2015, but this relationship is more attenuated in 2015 compared to 2000, particularly for firms with more than 100 workers. If the marginal product is proportional to the average product of labour, and profit-maximising firms equate the marginal product of labour to the cost of labour, then this suggests that the effective cost of labour has diminished for larger Indian firms compared to smaller firms.

Figure 1 Firm size distribution in 2000 and 2015

Note: Figure shows employment-weighted distribution of firm employment. Right panel shows coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from non-parametric regressions of log VA/Worker on log employment using Epanochnikov kernel with a bandwidth of 0.6. Employment is the number of non-managerial workers. Log VA/Worker is residualised by industry and year fixed effects.

Figure 2 Value added (VA) per worker by size in 2000 and 2015

Note: Figure shows coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from non-parametric regressions of log VA/Worker on log employment using Epanochnikov kernel with a bandwidth of 0.6. Employment is the number of non-managerial workers. Log VA/Worker is residualised by industry and year fixed effects.

Large firms adapt by outsourcing labour

In a recent study (Bertrand, Hsieh, and Tsivanidis 2021), we investigate how the decline in the bite of the IDA does not come from a legal change in Indian labour laws, but from the rapid development of the labour contracting industry in India since the early 2000s. The IDA only applies to a firm's full-time employees; workers supplied through third-party intermediaries are not considered firm employees for the purposes of the IDA. The contract workers are employees of the staffing companies, and the staffing companies themselves must abide by the IDA. This loophole provides customer firms with the flexibility to return the contract workers to the staffing company without being in violation of the IDA.

Figure 3 shows the probability that contract workers account for more than 50% of total firm employment as a function of total firm employment. Among smaller firms, there has been no discernible increase in the share of firms where contract labour is at least 50% of the workforce. In contrast, there has been a dramatic increase among larger firms, particularly those with more than 100 workers. We trace this increase to a 2001 Indian Supreme Court decision that made large firms less reticent to rely on a large pool of contract workers for "core" activities.

Figure 3 Contract labour use and firm size in 2000 and 2015

Note: Plot shows point estimates and 95% confidence intervals from non-parametric regression of the probability a plant hires more than 50% of its non-managerial workers through contractors on (log) non-managerial employment.

Implications for India’s future labour market

In sum, the relaxation of labour constraints facing large Indian firms since the early 2000s came from exploiting a loophole rather than a de jure change in Indian labour laws. In this sense, this episode is another example of what many people in India call “jugaad,” which roughly means finding informal solutions to problems. But as with all informal solutions, it potentially raises other costs that may make further progress difficult. In particular, one may be concerned about further growth potential when the most productive firms rely on contract labour for such a large share of their workforce. Future work should also consider the implications of this development for labour training, skill upgrading, and bargaining power.

Editors’ note: A version of this article first appeared on VoxEU.

References

Bertrand, M, C Hsieh, N Tsivanidis (2021), “Contract labour and firm growth in India”, NBER Working Paper 29151.

Hsieh, C and P Klenow (2014), “The Life-Cycle of Manufacturing Plants in India and Mexico,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(3): 89-108.

Hsieh, C and B Olken (2014), “The Missing Missing Middle”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28(3): 1403-1448.