A combination of information and cash transfers is effective in changing maternal behavioural practices, which could bring down malnutrition

Children in the developing world face substantial risk of malnutrition, including in South Asia, where malnutrition remains a large threat despite significant improvements in food availability. Nearly one in three children in South Asia were at risk of malnutrition in 2018 (UNICEF, World Bank, and WHO 2020). Much work therefore remains to ensure that all children around the world can begin their lives healthy, with an equal opportunity to succeed.

Governments around the world have attempted to use cash transfers as a tool to enhance child health and development; however, evidence on the effectiveness of cash transfers to reduce malnutrition remains mixed. A recent meta-analysis (Durao et al. 2020) found some evidence that cash transfers can improve food security and dietary diversity, but that they had small or no effects on stunting, wasting, or cognitive development.

Malnutrition in Nepal

In our study (Levere, Acharya and Bharadwaj 2022), we sought to better understand the critical barriers to achieving full nutrition for families and children in Nepal. The two primary barriers we sought to understand were (1) lack of information and (2) lack of money. We focused on Nepal because of its especially high rates of malnutrition – nearly half of children under five were at risk of malnutrition according to the most recent Nepal Living Standard Survey.1 The 2015 earthquake, which killed almost 9,000 people and may have led to economic losses as high as 35% of the country’s GDP, was an unexpected event in the middle of our study; this may have further worsened the situation for Nepal’s most vulnerable families.

Cash transfers and the potential for complementing with information

Cash transfers have been extensively studied throughout the developing world, with at least 63 countries offering some form of conditional cash transfer (Castagli et al. 2016). These programmes improve outcomes in the short term, although typically for slightly older children in attending school (Fiszbein and Schady 2009). A cash transfer programme in Nigeria for pregnant women improved health for young children up to the age of four (Carneiro et al. 2021), though these transfers represented 85% of monthly household income. A similar programme in Nicaragua improved child development (Macours et al. 2012).

Less is understood about the role of information in the perpetuation of malnutrition. Evidence from the Nigerian cash transfer programme suggests that the accompanying information sessions improved knowledge and ultimately behavioural practices (Carneiro et al. 2021). Many other cash transfer programmes, including the one in Nicaragua, also include an informational aspect (Macours et al. 2012). Yet it can be difficult to disentangle the effects of information given the presence of multi-faceted programmes.

Study design

We conducted an experiment in about 600 villages to evaluate the effects of information alone and information combined with a cash transfer. We randomly assigned all villages within a county to one of three groups: (1) those that received information alone (information-only); (2) those that received information together with a conditional cash transfer (information plus cash); and (3) a control group. The information session was for pregnant women and mothers with children under the age of two, and covered best practices regarding nutrition and health. The cash transfers were worth approximately US$7 per month, amounting to 8–20% of median monthly household income. To receive the cash transfer, women had to attend the information session.

The information was offered for nine months, while cash transfers were disbursed over five months. We collected data at the end of the nine months, as well as two years after the study was completed, to assess whether the programme improved maternal knowledge regarding infant health best practices, spurred behavioural changes, and ultimately improved child health and development.

Information improves knowledge; information and cash together change behaviour

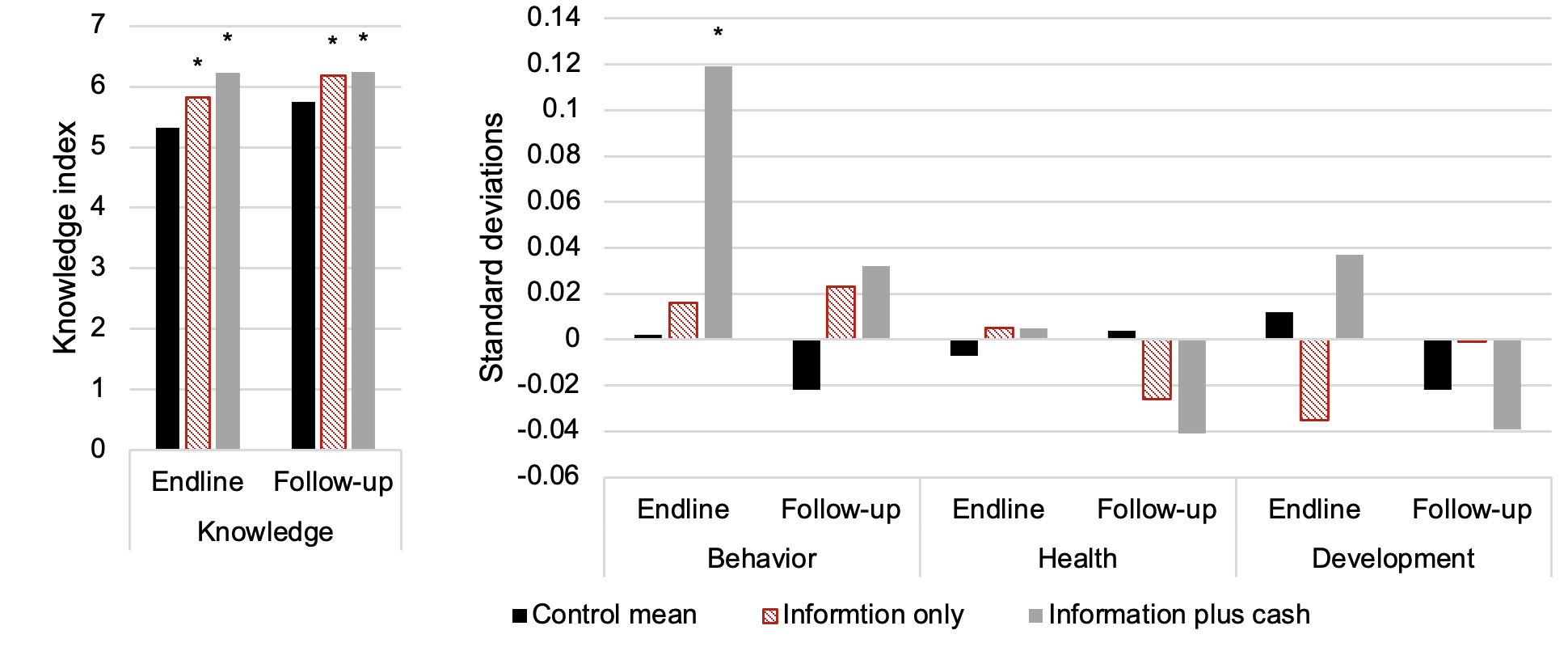

We found significant and sizable impacts on maternal knowledge regarding infant health in both the information-only and information plus cash groups. Women in the information plus cash group improved their knowledge relative to the control group by answering one more question correctly (out of ten asked) in the short run, with persistent effects of about half an additional question answered correctly two years after the intervention ended. Women in the information-only group also improved their knowledge relative to the control group in both the short and long run. The short-run improvement in knowledge was only about half as large for women in the information-only group compared to the information plus cash group, though long-run findings were similar.

For households in the information plus cash group, improvements in knowledge also translated into changes in behavioural practices. They consumed approximately 100 more calories per day than those in the control group, and women also improved various maternal behaviours such as breast feeding, vitamin A take-up, and prenatal visits. In the information-only group, the improvements in knowledge did not translate into changes in behaviours. Together, this points to the importance of cash in affecting behaviour, such as increased regular feeding for young children.

Figure 1 Impact on knowledge, behaviour, and children’s health and development outcomes

Notes: Information plus cash led to large improvements in knowledge that passed on to behaviour, though effects on children were limited. * indicates a statistically significant difference from the control mean at the 10 percent level.

Child health and development outcomes are slower to change

Despite improvements in knowledge and behavioural practices, the intervention had limited impacts on children’s outcomes. Relative to the control group, we found no improvements in either child health or development outcomes. We found suggestive evidence of improved child development in the short run, though, as children in the information plus cash group had slightly better outcomes than children in the information-only group. Additionally, the older siblings of children in the information plus cash group (aged 25–36 months at the start of the intervention) had relatively better health, in terms of height and weight, compared to the older siblings of the information-only group. In the long run, though, we did not find any sustained improvements in outcomes among either group. This is consistent with the research that finds limited or no effects of cash transfers on health and development outcomes (Durao et al. 2020).

An important limitation to our work is the short time frame of the intervention. Since the cash transfer was less than 20% of monthly income and only in place for five months, it may not have been sufficient to improve child outcomes in the long term. Research shows that the effects of cash can fade quickly after the cash is no longer being distributed (Baird et al. 2019).

Yet, despite the short time frame, the intervention led to sustained improvements in women’s knowledge and behavioural practices. Since women only received the cash transfer if they attended the information session, the transfer might primarily serve to magnify the effects of the information. Our findings thus indicate that information can be a critical component of a set of strategies to address malnutrition, particularly when offered alongside cash payments. Ensuring that the quality of information provided is more reliable that what is already available is critical to creating this impact.

Build on existing pathways and networks

A critical element of our intervention was using existing social infrastructure and trusted partners to deliver information and cash. The information aspect of our intervention was added to ongoing monthly community meetings that sought to improve economic outcomes. Local health workers who led these meetings had existing relationships with these communities. Using the pre-existing social capital, developed through local health workers, builds on the premise that existing capacity and institutional structures should be used to deliver information efficiently without needing to create new pathways. Women were presumably more likely to internalise and act upon new knowledge acquired as part of the intervention due to prior trusting relationships with local health workers. Using existing health and financial infrastructures allowed for overall lower costs, easier replication, and potential scale-up.

References

Baird, S, C McIntosh and B Özler (2019), “When the money runs out: Do cash transfers have sustained effects on human capital accumulation?”, Journal of Development Economics 140: 169-185.

Bastagli, F, J Hagen-Zanker, L Harman, V Barca, G Sturge and T Schmidt, with L Pellerano (2016), Cash transfers: what does the evidence say?, Overseas Development Institute.

Carneiro, P, L Kraftman, G Mason, L Moore, I Rasul and M Scott (2021), “The impacts of a multifaceted pre-natal intervention on human capital accumulation in early life”, American Economic Review 111(8): 2506-2549.

Durao, S, M E Visser, V Ramokolo et al. (2020), “Community-level interventions for improving access to food in low- and middle-income countries”, Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews 8.

Fiszbein, A and N Schady (2009), Conditional cash transfers: Reducing present and future poverty, World Bank.

UNICEF, World Bank, and World Health Organization (2020), Levels and trends in child malnutrition: Key findings of the 2019 edition of the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates.

Levere, M, G Acharya and P Bharadwaj (2022), “The role of information and cash transfers on early childhood development: Evidence from Nepal”, NBER Working Paper No. 22640.

Macours, K, N Schady and R Vakis (2012), “Cash transfers, behavioural changes, and cognitive development in early childhood: Evidence from a randomized experiment”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 4(2): 247-73.

Endnotes

1 Nepal Living Standard Survey, Third Round (NLSS-III 2010-11).