Evidence from Mali shows that patient demand is an important contributor to the overuse of antimalarials

Removing barriers to life-saving medical care is a critical goal for national health systems, and many countries in sub-Saharan Africa have begun to heavily subsidise primary care to achieve it. Yet even as these efforts are underway, another challenge is emerging: preventing the overuse of care. When patients consume unnecessary medical treatment, or get treated for the wrong illness, they waste precious time and money, and could experience harmful side effects. For health systems as a whole, overmedication contributes to the rise of drug-resistant diseases that will cost lives in the future. Overuse of government-subsidised care strains already tight public budgets.

Despite prescription drug systems and licensing requirements for physicians and pharmacists, many, if not most, healthcare systems battle high rates of overtreatment. This includes countries where one might think that the main challenge is to provide more, not less treatment. For example, the overuse of antibiotics has been documented in a wide range of lower-income countries (Li et al. 2012). Injections are overused across the developing world (van Staa and Hardon 1996). A large share of antimalarials prescribed at health centres in sub-Saharan Africa go to patients who test negative for malaria (Reyburn et al. 2004). In our study setting, Bamako, Mali, we find that 58% of malaria-negative patients who visited community clinics for an acute illness received an antimalarial, and a large share of these prescriptions were expensive injections usually reserved for life-threatening complications (Lopez et al. 2019).

Who drives overtreatment?

Most of the existing literature focuses on reasons why the prescribing physician may want to over-treat. An important reason is that the doctor’s own income may depend on the revenue from medication sales (Currie et al. 2014). The doctor may also be unsure about correct treatment protocols, or treat pre-emptively to avoid complications later (Das et al. 2008). Since patients cannot verify the true cause of their illness, they must rely on the doctor’s recommendation. But as Kotwani et al. (2010) note, doctors often report that patients pressure them to overprescribe. If the doctor cannot persuade the patient that medication is not needed, he/she may write a prescription just to keep the patient satisfied.

This is also true in our sampled clinics in Bamako, where over half of the doctors interviewed reported that patients sometimes request unnecessary drugs. This alternative explanation is much less explored in the literature: could it be that patients put pressure on doctors to prescribe certain medications, and doctors acquiesce even though they do not think the treatment is necessary?

Understanding who drives overuse of antimalarials

We focus on (over)-treatment for malaria, because malaria is one of the most commonly treated illnesses in clinics, and a patient can be easily diagnosed with a free 20-minute blood test. Malaria is still the leading cause of mortality in Mali, accounting for roughly 20% of all deaths (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2016). As concerns over parasite resistance to drugs are growing, Malian health policies mandate that antimalarials should only be prescribed after a positive malaria test result, and free rapid detection tests should be available to all patients (Ministère de la Santé 2013). Mali’s medical guidelines advise the treatment of “uncomplicated” malaria with Artemisinin Combination Therapy (ACT) tablets, reserving more expensive antimalarial injections for patients in acute crisis.

From prescription and use data alone, it is difficult to identify the causes of overmedication. We therefore designed a randomised experiment that allows us to identify whether the patient demand channel drives the overuse of antimalarials. We worked in 60 public health clinics in Bamako and stationed study staff at each clinic for a two-week period. We recorded details of all acutely ill patients who came to seek treatment: their symptoms, what medications they were prescribed, and what medications they bought. We also visited a share of these patients at home a day later to conduct a malaria test.

In total, we interviewed 2,055 patients visiting study clinics. On a randomly selected subset of study days, we offered vouchers for free ACT tablets. In order to test for the patient demand channel, we offered these vouchers in two different ways:

- On randomly selected “Patient Days,” we gave the vouchers directly to patients when they arrived at the clinic. This way, patients knew that the ACT could be obtained for free before they consulted the doctor.

- On randomly selected “Doctor Days,” we gave the same vouchers to doctors to dispense at their discretion, without informing patients that treatment was free. On Doctor Days, physicians could choose if they wanted to inform patients of the discount for the ACT.

The discount offered exactly the same treatment for both types of days (ACT tablets for uncomplicated malaria) and had identical appearances and redemption conditions (to be valid, the voucher could only be used on the day of the clinic visit and required a doctor’s signature and ACT prescription). Hence, the sole difference between the “Doctor” and “Patient” days was whether patients knew about the voucher before their consultation and therefore had the ability to actively demand the discounted medication from the doctor. From the doctor’s perspective, all other factors that might influence their prescription decision remained the same: the revenue for the clinic, the patient’s need for treatment (i.e. malaria status), and the actual price the patient would have to pay (after applying the voucher).

Patient demand driving overuse

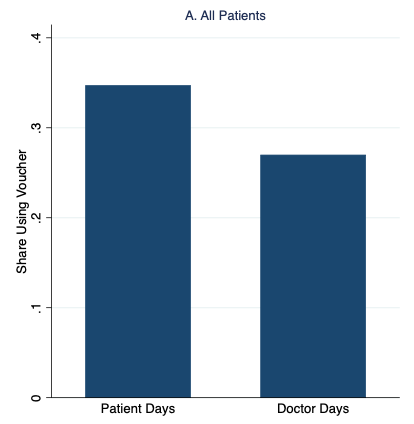

Figure 1 shows our main results. Patients were 35% more likely to redeem the vouchers and receive malaria treatment on “Patient Days” than on “Doctor Days”. The additional demand and voucher redemptions were entirely driven by patients with the fewest malaria symptoms. These results strongly support the patient demand channel. This is because if doctors were driving overuse (e.g. to generate more revenue to the clinic), they would share information about the vouchers with low risk patients in an effort to increase sales. We see the opposite, which suggests that doctors prefer not to prescribe to patients who are least likely to have malaria.

Figure 1Rates of malaria voucher redemption by treatment condition and patient malaria risk based on symptoms

Notes: High- and low-risk patients have above- and below-median malaria risk based on reported symptoms, respectively.

Matching purchases with malaria status

We also analysed the match between prescriptions/purchases and patients’ malaria status. We studied the probability of:

- a “correct positive” – a malaria positive patient receives an antimalarial, and

- a “correct negative” – a malaria negative patient does not take an antimalarial.

This enabled us to create a measure of expected “match” of treatment and illness.

Our results indicate that, relative to the control when ACTs were sold at the normal price, the voucher treatments did not increase correct positives for prescriptions, but they did for medication purchases (by 15-19%). This result underscores the rationale of subsidising health care: some truly sick patients underuse care, possibly at high risk and perhaps for financial reasons. On the other hand, we also found that both voucher conditions decreased the likelihood of a correct negative, because more patients without malaria purchased an antimalarial. Strikingly, however, while “Doctor Days” decreased the share of correct negatives by 14%, “Patient Days” decreased it by 24%. Overall, we estimate that on “Patient Days” there is a decline in the match rate that amounts to a 19% increase in misallocation.

Testing whether doctors drive the overuse

Our research design also allows us to test if doctors might actually drive overuse of malaria drugs. This is because an often-used alternative to simple ACT tablets are expensive antimalarial injections, which the voucher intentionally did not cover. On doctor days, doctors could take advantage of the option to keep the vouchers to themselves and “upsell” patients on an injection instead. However, if anything, we found injection rates decreased by more on Doctor Days than on Patient Days. Our results show that marginal misallocation from price subsidies is attributable to patient preferences in our context.

Health policy implications

Our results indicate that doctors and patients do not always agree about what medications should be prescribed. In our setting, the disagreement is not always that doctors are eager to sell expensive treatment options that the patients are reluctant to purchase – an often-invoked explanation for overly costly healthcare and unnecessary treatment choices. Rather, sometimes low-risk patients demand access to medication that doctors prefer to withhold. However, when faced with patients who know that treatment is free, some doctors give in and write a prescription anyway. In other words, the heightened demand from these patients can in some cases exert enough pressure on doctors so that they go against their own professional judgement.

Providing subsidised antimalarials is an essential tool to overcome access barriers in the fight against malaria. However, these subsidies can get very costly if doctors do not limit treatment to those who need it. It is therefore critical for policymakers to understand how well doctors fulfil their gatekeeping role for antimalarials as well as other prescription drugs, and why they fall short. Here, it is important to keep in mind that doctor-patient preference gaps may be different in other contexts where doctors face different incentives and patients face different prices. In situations where patients drive overtreatment, interventions that empower doctors and make it easier for them to resist patient demands (like patient communication tools) could help sustain subsidies and reduce overtreatment. In settings where doctors drive overtreatment, on the other hand, policy instruments may be required that limit doctors’ discretion to prescribe or change their financial incentives, such as closer monitoring (e.g. by conducting independent malaria tests) or subsidy reimbursement caps.

Editors' note: A version of this column first appeared on VoxEU.

References

Currie, J, W Lin and J Meng (2014), “Addressing antibiotic abuse in China: An experimental audit study”, Journal of Development Economics, 110: 39–51.

Das, J, J Hammer and K Leonard (2008), “The quality of medical advice in low-income countries”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2): 93–114.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2016), “Global burden of disease study 2015 (gbd 2015) results”. Online. Accessed August 22, 2016.

Kotwani, A, C Wattal, S Katewa, P Joshi and K Holloway (2010), “Factors influencing primary care physicians to prescribe antibiotics in Delhi India”, Family Practice, 27(6): 684–690.

Li, Y, J Xu, F Wang, B Wang, L Liu, W Hou, H Fan, Y Tong, J Zhang and Z Lu (2012), “Overprescribing in China, driven by financial incentives, results in very high use of antibiotics, injections, and corticosteroids”, Health Affairs 31(5): 1075–1082.

Lopez, C, A Sautmann and S Schaner (2019), “The contribution of patients and providers to the overuse of prescription drugs”, NBER Working Paper No. 25284.

Ministère de la Santé (2013, August), “Politique Nationale De Lutte Contre Le Paludisme. Republique du Mali”.

Reyburn, H, R Mbatia, C Drakeley, I Carneiro, E Mwakasungula, O Mwerinde, K Saganda, J Shao, A Kitua, R Olomi, B Greenwood and C Whitty (2004), “Over-diagnosis of malaria in patients with severe febrile illness in Tanzania: A prospective study”, British Medical Journal, 329(7476): 1212.

Van Staa, A and A Hardon (1996), “Injection practices in the developing world”, World Health Organization.