Criminalising sex work in Indonesia led to large increases in sexually transmitted infections among sex workers and likely across the whole population

The regulation of sex work, which exists around the world with varying degrees of legality, is a hotly debated topic – not only as a moral and human rights issue, but also because of the role sex markets play in the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In 2015, Amnesty International called for the decriminalisation of sex work as the best way to defend sex workers against human rights violations and exclusion from health care, while a Lancet series claimed that decriminalising sex work would have the greatest effect on the course of HIV epidemics (Amnesty International 2015, Lancet 2015).

Despite these claims, empirical evidence on the consequences of regulating sex markets is sparse, particularly in lower income countries. Most previous studies explore the impact of decriminalising sex markets in high-income countries (Bisschop et al. 2017, Cunningham and Shah 2018, and Nguyen 2016). While these studies have found that decriminalising sex work has positive impacts on the health of sex workers and the general population, it is unclear whether criminalising sex work would have the opposite impacts and whether these impacts would carry over to lower income countries.

In a recent study (Cameron, Seager and Shah 2020), we analyse the impact of criminalising sex work in a low-income setting, where the sex market has been a key driver of the HIV epidemic, and a larger share of women participate in sex markets.

The natural experiment

In 2014, the government of a district in East Java (Malang), Indonesia unexpectedly announced that it would be closing all formal sex work locations. This provided the perfect opportunity to examine the impact of criminalisation by comparing what happened in the district where sex work was criminalised with neighbouring districts (Pasuruan and Batu) where sex work remained legal and business continued as usual (see Figure 1 for more detail).

Figure 1 Study area map

The data

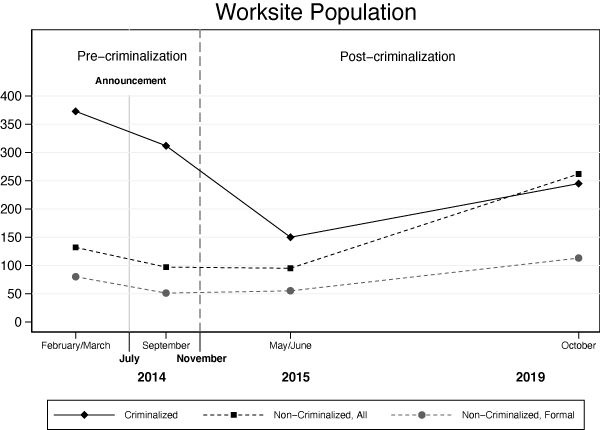

In July 2014, we had just completed implementing baseline surveys and were about to begin offering bank accounts to female sex workers in East Java as part of a planned randomised controlled trial trying to reduce risky sexual behaviour. This was when the local government announced that all formal sex work locations in the district would close in November of that year. While we were no longer able to implement our intervention, we shifted gears to examine the impact of the criminalisation on the sex workers, their clients, and their families. Figure 2 shows the timeline of data collection relative to the announcement and closure of the formal worksites.

Figure 2 Study timeline

Approximately six months after criminalisation came into effect, we collected a second round of data on the same women we interviewed at baseline and other sex workers we found at the sex work sites. Importantly, we collected biological samples from vaginal swabs from sex workers both before and after criminalisation. We had also collected data on clients at baseline and did so again at endline. We thus were able to utilise a unique panel dataset on sex workers with biological markers covering the period from pre-criminalisation to post-criminalisation, in tandem with two rounds of data on clients. To identify the longer-term trajectory of the sex market, we also collected information on sex market size in October 2019, approximately five years after criminalisation.

These unusual and rich data sets enabled us to employ a difference-in-differences strategy to examine not only the direct impact of criminalisation on the size of the market and sex worker STI rates, but also the impacts on the economic and social well-being of the women who left sex work, and the probability of STI transmission to the general population.

What happened?

The sex market shrank

The immediate impact of the criminalisation was evident in the shrinkage of the sex market. The number of sex workers working at the criminalised sites dropped markedly between September 2014 and May/June 2015 (see Figure 3). The same decrease was not evident at non-criminalised sites.

Figure 3 Impact of criminalisation on sex worker population

STI rates increased

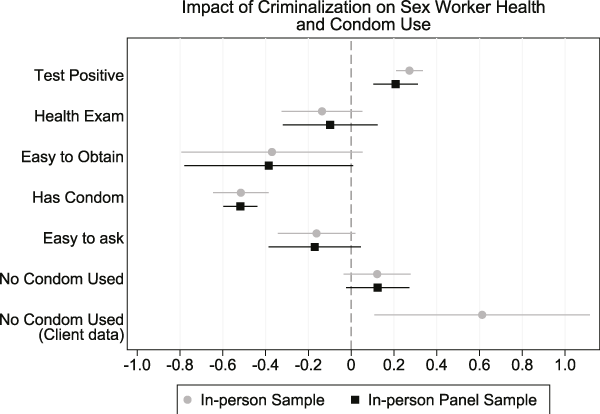

The biological test results showed that STI rates among sex workers increased by 27.3 percentage points, or 58% relative to areas where sex work was not criminalised. This is a large increase. Data from both sex workers and clients suggest that this was driven by lower access to condoms, an increase in condom prices, and an increase in non-condom sex. Sex workers were 50 percentage points less likely to be able to produce a condom when asked by survey enumerators at endline, and clients report a 61 percentage point increase in non-condom sex. See Figure 4 for a summary of the main impacts.

Figure 4 Estimates of criminalisation impacts

There were no changes in the volume of clients a sex worker was seeing, the type of sex she engaged in, nor in the types of clients (age, education, marital status, willingness to take risks, and wealth). This is true in the data reported by both sex workers and clients. We were also able to rule out that the results are driven by changes in sample composition due to sex workers leaving our sample.

The well-being of sex workers who were forced out of sex work suffered

Criminalisation of sex work is often designed to force women out of sex work. Our results show that women who left sex work because of criminalisation (not by choice) ended up with lower earnings and had greater difficulty affording an education for their children. Their children were also more likely to work to supplement household income, and these women were more likely to report being very unhappy.

General population STI transmission likely increased

The health effects of criminalising sex work go beyond affecting the sex workers themselves. They have implications for the general population through STI transmission from sex workers to clients and to the partners of both. While the size of the sex market shrank by about 60% in the short run, decreasing the probability of STI transmission to the general adult population, five years later the sex market rebounded to a size similar to that before criminalisation. In the long-run, the increase in STI prevalence among female sex workers implies an increase in the probability of STI transmission to the general population of between 22 and 59.3% for men and between 13.6 and 48.3% for women, depending on the assumptions we make about the changing size of the market.

Conclusion

Many people find sex work morally repugnant. To the extent that the size of the sex market in Indonesia may be smaller now than it would have been in the absence of criminalisation, one may assess criminalisation as having been successful. However, from a public health perspective, criminalisation of sex work is counterproductive and can reverse the good work that many government health departments and NGOs are undertaking to reduce the spread of STIs and HIV/AIDS.

A common response to our findings is to argue for criminalisation alongside the provision of condoms and health services. Such arguments, however, ignore the fact that it is criminalisation that restricts the ability of organisations to support the health of sex workers and inhibits their ability to openly access support and services.

References

Amnesty International (2015), “Global Movement Votes to Adopt Policy to Protect Human Rights of Sex Workers”, Press Release.

Bisschop, P, S Kastoryano and B van der Klaauw (2017), “Street Prostitution Zones and Crime”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9(4):28–63.

Cameron, L, J Seager and M Shah (2020), “Crimes against Morality: Unintended Consequences of Criminalizing Sex Work”, Quarterly Journal of Economics qja0032.

Cunningham, S and M Shah (2018), “Decriminalizing Indoor Prostitution: Implications for Sexual Violence and Public Health”, The Review of Economic Studies 85(3): 1683–1715.

Lancet (2015), “Keeping sex workers safe”, The Lancet 386(9993): 504.

Nguyen, A (2016), “Optimal Regulation of Illegal Goods: The Case of Massage Licensing and Prostitution”, UCLA Working Paper.