A low-cost brief telecounselling intervention effectively improved women’s mental health in Bangladesh during the COVID-19 pandemic

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has had a severe impact on employment, incomes, and the livelihoods of millions of households worldwide. While most countries focused on the containment of the disease itself and correcting the macroeconomic repercussions of lockdowns, the adverse effects of the pandemic extended well beyond income shocks and food insecurity (Fetzer et al. 2020).

According to the Global Burden of Disease study (Santomauro et al. 2021), the global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by about 25% during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic led to a 27.6% and 25.6% increase in people with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder, respectively. The pandemic-related misinformation and uncertainty caused fear, worry, and stress (Islam et al. 2021), so it is quite understandable that such mental health issues increased during the pandemic. In addition to the fear of contracting the virus, the government-imposed lockdowns - essential to contain the virus and save lives - led to unprecedented stress and anxiety caused by the social isolation that came with lengthy and periodic lockdowns, social distancing measures, loss of employment, school closures, loss of loved ones, and the inability to engage with family and friends and the community. Consequently, loneliness, fear of infection, and loss of loved ones have been identified as some of the critical factors that led to widespread mental health issues.

In low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), both the economic and public health effects have been devastating as these governments are more resource-constrained and individuals lack strong safety nets. Women are more vulnerable to the pandemic compared to men (Afridi et al. 2021, Bau et al. 2022), particularly in LMICs, as they are responsible for increased household responsibilities, and elderly and child care (United Nations 2020, Giurge et al. 2021). Thus, the pandemic induced high levels of pressure on their time, and increased stress, while they had no access to any kind of support or counselling.

Though the mental health impact of the pandemic has improved by the end of 2021, the pandemic has highlighted the importance of mental health for overall wellbeing and exposed the immediate need for affordable, practical and feasible strategies to protect the mental health of vulnerable groups during similar epidemics, natural disasters and conflicts, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Context and intervention

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of people in Bangladesh experienced a sharp decline in income owing to partial or complete loss of employment and livelihood (Genoni et al. 2020, Beam et al. 2021, Rahman et al. 2021), and a majority of rural households fell into poverty and were exposed to food insecurity (Ahmed et al. 2021), which contributed to mental health problems such as stress, anxiety, and depression.

Women in rural areas of Bangladesh are often susceptible to severe mental health issues owing to their disadvantageous socioeconomic position and the disproportionate burden of household chores and unpaid care responsibilities within the household. With minimum mental health care services available nationally, the mental health needs of women in rural areas remain unmet. Addressing this unmet need, we examine if a telecounselling intervention aimed at providing psychological support can be effective in addressing mental health problems in such low-income and resource-constrained settings (Vlassopoulos et al. 2023).

We conducted the study across 357 villages in Southwestern Bangladesh between May 2020 and August 2021. The baseline survey, conducted in May-June 2020, revealed that an alarming 83% of respondents were stressed, having a perceived stress scale score exceeding 13 out of 40 (Cohen et al. 1983, 1997) suggesting a high level of stress among rural Bangladeshi women during the pandemic and the need for immediate action.

Out of 2,402 participants, 1,299 were offered over-the-phone psychological support. The remaining participants were in the control group, which received no intervention during the intervention period—July to October 2020. The intervention was specifically designed and offered to the targeted participants via four brief mental health counselling sessions. It was developed and adapted to the needs of the local context by drawing on the mental health guidelines prescribed by the International Federation of Red Cross (2020), the World Health Organization (2020) and Brooks et al. (2020). The four modules covered four broad elements:

- Behavioural: problem-solving, behavioural activation, relaxation, and exposure;

- Interpersonal: identifying/eliciting support and communication skills;

- Emotional: linking affect to events and emotional regulation and processing; and

- Cognitive: identifying thoughts, insight building, distraction, and mindfulness.

While the first session of the intervention focused on information and awareness related to the COVID-19 disease, symptoms, and preventive measures, the rest of the sessions covered different strategies to cope with stress and anxiety (e.g. stress management techniques, self and self-care - i.e. knowing, recognising and managing one’s emotions, and the relevance of improved communication with loved ones via mobile phones), thereby empowering participants with ways to look after their emotional wellbeing, where no other support system is available. The widespread use of mobile phones in rural Bangladesh (94%) facilitated this type of intervention.

The sessions were scheduled to be delivered remotely over the phone, at times convenient to the participants. These sessions were delivered by a group of locally recruited female para-counsellors, with recent graduate degrees in either psychology, public health, or social sciences and trained by a public health expert (a co-author in the paper) and a psychologist. Each of the four sessions lasted about 25-30 minutes and were spaced every two weeks, thus providing a total intervention dosage of about 2 hours.

Results

To evaluate the impact of the intervention, the endline survey was conducted in November 2020 (one month after the end of the intervention), with a follow-up survey in August 2021—ten months after the intervention was completed. The results suggest that the intervention had a significant positive impact on the mental health and wellbeing of the women who received it. Among the treated women, there was a reduction of 26% in the incidence of moderate and severe stress, and a 60% decrease in the case of depression one month after the completion of the intervention, in comparison to the control group. These effects were found to persist even 10 months after the intervention ended. We observed reductions of 20% and 33% for stress and depression, respectively, after 10 months.

Figure 1: Mental health over time, by treatment status.

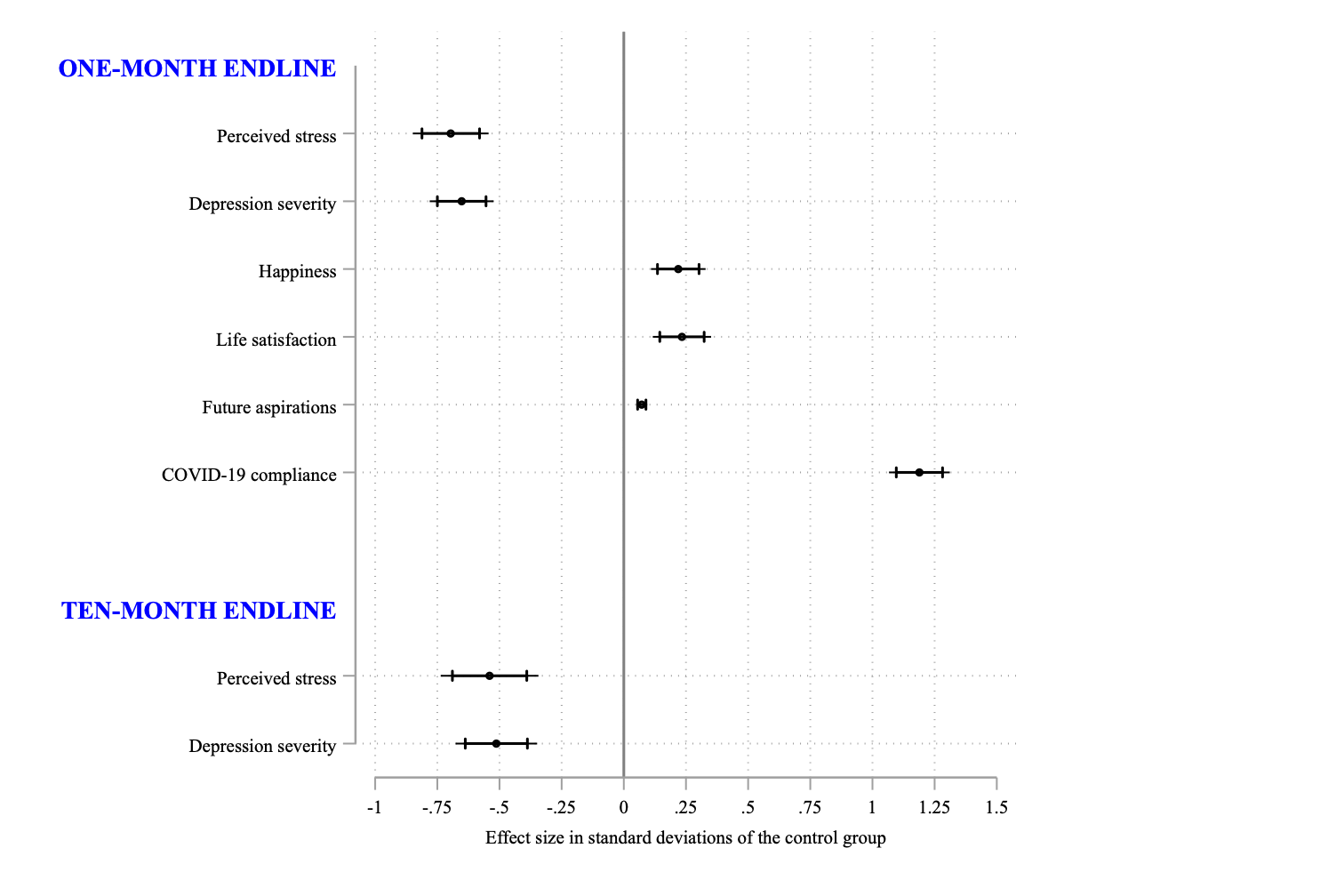

The intervention reduced perceived stress level by 0.7 SD and severity of depression by 0.65 SD among the targeted participants, compared to the women in the control group. We also find evidence that the psychological support improved subjective wellbeing captured via levels of happiness and life satisfaction by 7.8% (0.22 SD) and 8.2% (0.24 SD) relative to the control group, respectively. After 10 months, treated women continued to experience positive effects. Their perceived stress levels and depression severity were found to be 0.55 SD and 0.51 SD, respectively, lower than those in the control group.

Figure 2a: Treatment effects in standard deviation units, along with 99% and 95% confidence intervals.

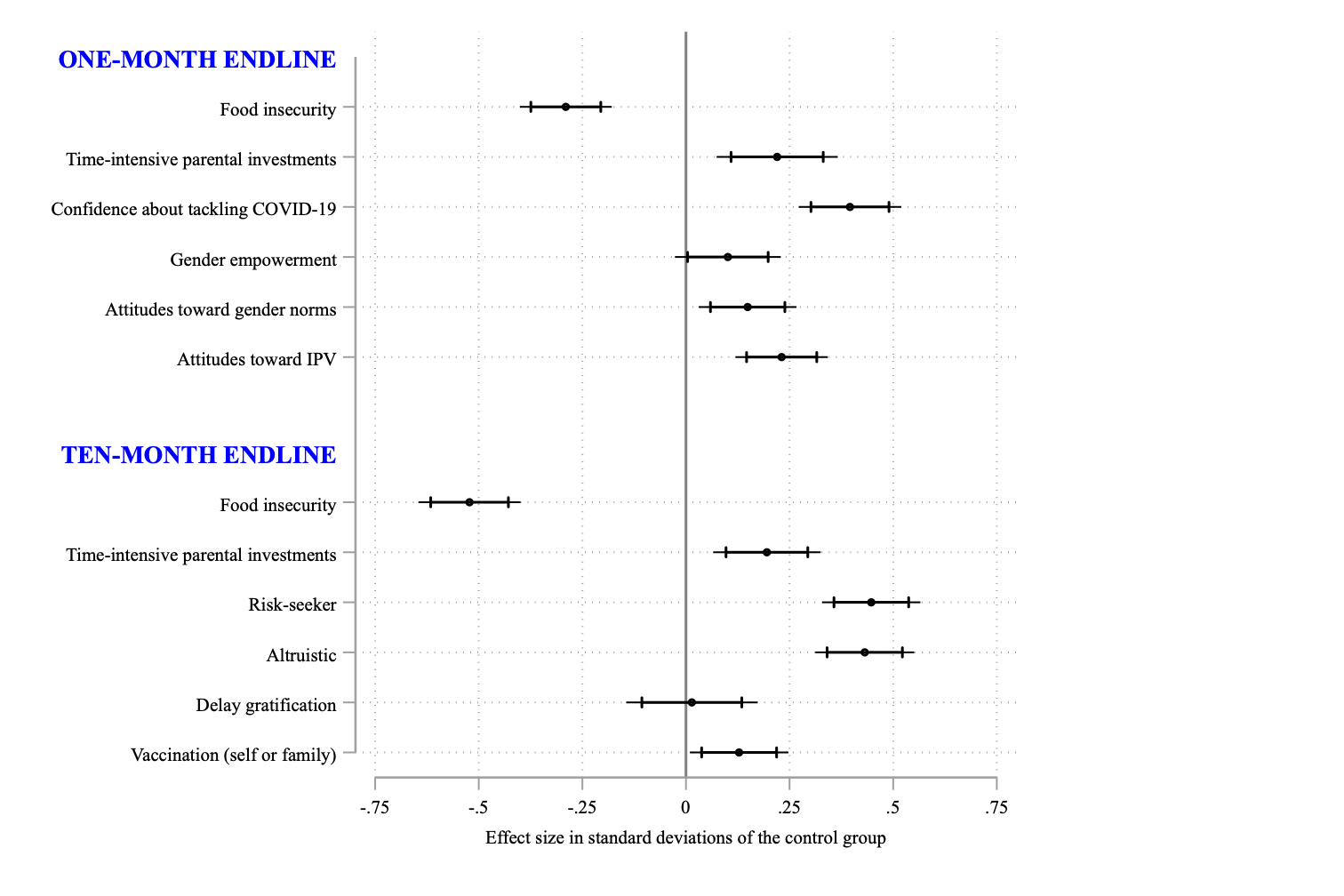

- The programme also had a significant impact on other outcomes (all effects reported below are highly statistically significant). These include:

- Incidence of household-level food insecurity declined by 31% (0.28 SD)

- Compliance with COVID-19 precautionary guidelines improved by 22% (1.19 SD) and confidence to tackle COVID-19 issues increased by 11% (0.40 SD)

- Time-intensive parental investment in children (education and playtime combined) increased by 7% (0.22 SD)

- Gender empowerment improved by 8% (0.10 SD)

- Improved attitudes toward gender norms by 7% (0.15 SD)

- Improved attitudes toward intimate partner abuse by 13% (0.23 SD)

- Future aspirations related to different aspects of life improved by 10% (0.37 SD)

Figure 2b: Treatment effects in standard deviation units, along with 99% and 95% confidence intervals.

The counselling sessions were most effective in improving mental health for women who had a higher level of stress to begin with (at baseline), were older, and came from households with incomes below the median.

When looking into why the intervention had a lasting effect on mental health, we found that women kept using the mental health techniques they learned via telecounselling. The programme also motivated them to take more informal borrowings and begin new income-generating activities, which could be why their food security improved. Such actions may have also made them feel more empowered and changed the gender dynamics within households.

Summary and policy implications

Overall, the study suggests that a low-cost brief telecounselling intervention can effectively improve the mental health of women in a resource-poor setting lacking access to mental health services. These rural women were affected by exposure to economic uncertainty and turmoil, which adversely impacted their mental well-being. The intervention positively impacted their overall happiness and wellbeing, their sense of empowerment and attitudes towards gender norms, food security and time investment on children, and compliance with prescribed health guidelines related to COVID-19 prevention.

The remote and empowering nature of the intervention coupled with the low cost of implementation (roughly US$14 per treatment delivery, including training and staff costs) makes the study scalable and its application in other similar contexts possible, where providing mental health support is otherwise challenging during a crisis.

The study resonates with the concerns of Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General “This is a wake-up call to all countries to pay more attention to mental health and do a better job of supporting their populations’ mental health.” The study suggests a light touch intervention that combines the provision of reliable information and building participants’ skills in managing their emotions through simple practices. The approach holds the potential to help address mental health crises, especially within resource-constrained environments.

References

Ahmed, F, A Islam, D Pakrashi, T Rahman, and A Siddique (2021), “Determinants and Dynamics of Food Insecurity During COVID-19 in Rural Bangladesh,” Food Policy, 101: 102066.

Afridi, F, A Dhillon, S Roy, et al. (2021), “The gendered crisis: livelihoods and mental well-being in India during COVID-19,” World Institute for Development Economic Research (UNU-WIDER).

Bau, N, G Khanna, C Low, M Shah, S Sharmin, and A Voena (2022), “Women’s Well-being During a Pandemic and its Containment,” Journal of Development Economics, 156: 102839.

Beam, E, S Chaparala, S Chaterji, and P Mukherjee (2021), “Impacts of the Pandemic on Vulnerable Households in Bangladesh,” IGC, S-20130-BGD-1.

Cohen, S, R C Kessler, and L U Gordon (1997), Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists, Oxford University Press.

Cohen, S, T Kamarck, and R Mermelstein (1983), “A global measure of perceived stress,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 385–396.

Fetzer, T, L Hensel, J Hermle, and C Roth (2020), “Coronavirus perceptions and economic anxiety,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–36.

Genoni, M E, A I Khan, N Krishnan, N Palaniswamy, and W Raza (2020), “Losing Livelihoods: The Labor Market Impacts of COVID-19 in Bangladesh,” World Bank.

Giurge, L M, A V Whillans, and A Yemiscigil (2021), “A multicountry perspective on gender differences in time use during COVID-19,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(12).

Islam, A, C Wang, M Vlassopoulos, and D Pakrashi (2021), “Stigma and Misconception in the time of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Field Experiment in India,” Social Science and Medicine, 278: 113966.

Rahman, T, M G Hasnain, and A Islam (2021), “Food insecurity and mental health of women during COVID-19: Evidence from a developing country,” PLoS ONE, 16(7): e0255392.

Santomauro, D F, A M Mantilla Herrera, J Shadid, et al. (2021), Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Lancet, 398(10312): 1700–1712.

United Nations (2020), “COVID-19 Bangladesh Rapid Gender Analysis,” [Online; Accessed June 01, 2020].

Vlassopoulos, M, A Siddique, T Rahman, D Pakrashi, A Islam, and F Ahmed forthcoming, "Improving Women's Mental Health During a Pandemic," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.