China's autocratic political regime and the rapid innovation in its AI sector mutually reinforce each other

Editor's note: A version of this article previously appeared on VoxEU.

Scholars have hailed AI technology as the basis for a “fourth industrial revolution” (Schwab 2016) – a general purpose technology predicted to bring productivity gains, drive economic growth, and transform the world in which we live (Bughin and Hazan 2017, Aghion et al. 2018, Agrawal et al. 2018, Brynjolfsson et al. 2019). But they have also warned of a dark side to this technological progress: AI, it has been argued, might be a technology that undermines democratic institutions (Acemoglu 2021a 2021b), enhances autocrats’ aims of social control (Tirole 2021) and constrains citizens by empowering “surveillance capitalists” (Zuboff 2019). These fears have long been expressed in fictional depictions of AI, from Farenheit 451, to 2001: A Space Odyssey, to The Matrix, and beyond. Is a dystopian, autocratic AI future merely science fiction, or could it be social science fact?

AI technologies, indeed, have characteristics that could result in a mutually reinforcing relationship between AI innovation and modern autocracy – the sort of relationship that could sustain an “AI-tocracy” equilibrium that many fear. As a technology of prediction, AI may be particularly effective at enhancing autocrats’ social and political control. Furthermore, because government data is an input into developing AI prediction algorithms and can be shared across multiple purposes (Beraja, Yang and Yuchtman 2023), autocrats’ collection and processing of data for purposes of political control may directly stimulate AI innovation for the broader commercial market, far beyond government applications. More general forms of spillovers from autocrats’ demand for AI technology may also be present – for example, arising from economies of scale or scope, the production of intangible assets, and externalities.

In the context of facial recognition AI in China, a recent paper of ours (Beraja, Kao, Yang and Yuchtman 2023) empirically tests for a mutually reinforcing relationship between frontier AI innovation and the political control objectives of autocrats. Our empirical setting is particularly suitable: maintaining political control is a paramount objective of the ruling Chinese Communist Party. All citizens, even China's most successful entrepreneurs are threatened by an unconstrained autocrat's ability to violate their property rights and, at times, their civil rights. Moreover, facial recognition is one of the most important fields of AI technology, with China among the world's leaders in this area.

We begin by examining the first direction in a mutually reinforcing relationship: whether AI technology can enhance autocrats' political control. We first test whether the Chinese regime, acting in a decentralized manner, responds to political unrest by procuring facial recognition AI technology. To do so, we combine data on episodes of local political unrest in China, from the GDELT project, with information on local public security agencies' procurement of facial recognition AI, from China's Ministry of Finance.

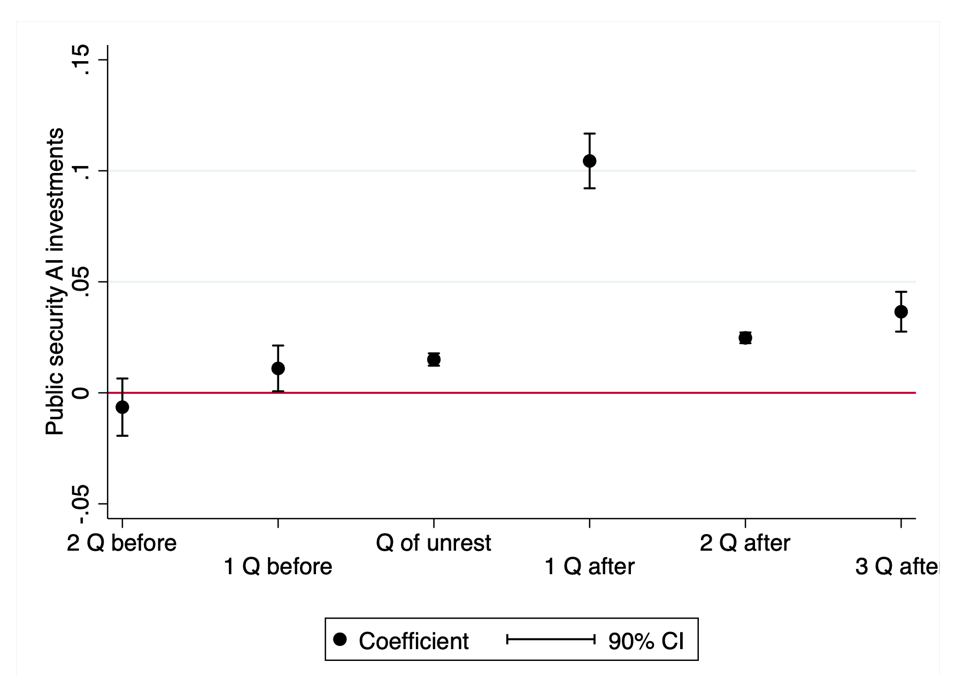

Using a difference-in-differences empirical strategy, we find that locations experiencing episodes of political unrest increase their public security procurement of facial recognition AI. One might still wonder whether the procurement of public security AI was already on a different trend in locations experiencing political unrest (e.g. because of different rates of economic growth). However, we find that public security agencies significantly increase their procurement of AI in the quarter after unrest (with diminishing effects lasting for another two quarters), with minimal increases in AI procurement preceding episodes of political unrest (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Public security AI investments (per million local residents) relative to the quarter of local political unrest.

Consistent with our interpretation that the Chinese government procures AI as part of an effort to enhance political control, we also find that locations experiencing political unrest purchase more high-resolution video cameras, which provide the crucial data input for facial recognition technology.

Local governments' purchases of AI technology for public security purposes in response to the occurrence of political unrest suggest at least their belief in the effectiveness of such technology in curbing future unrest. We next study whether the increased public security AI procurement does in fact enhance autocrats' political control. Precisely because we found that AI is procured endogenously in locations susceptible to political unrest, we do not examine the relationship between AI procurement and subsequent local protests. Instead, we examine how past investment in public security AI mitigates the impact of exogenous shocks that tend to instigate political unrest.

Specifically, we test whether local weather conditions conducive to unrest (good weather makes a protest more likely) have smaller effects on contemporaneous unrest in Chinese prefectures that had previously invested in public security AI. Indeed, we find that past local public security AI procurement significantly weakens the observed effect of good whether on local unrest. This is not simply a result of prefectures that procured this AI being richer, more technologically advanced, or having better governance. To rule out that possibility, we examine the effects of past AI procurement for non-public security purposes – such procurement would reflect a richer, more technologically advanced, and better-governed locality. But, importantly, we find no effect of past non-public security AI procurement, suggesting that our results are driven by the deployment of public security AI per se. We also find that the geographic spread of political unrest across prefectures is limited by the past procurement of public security AI.

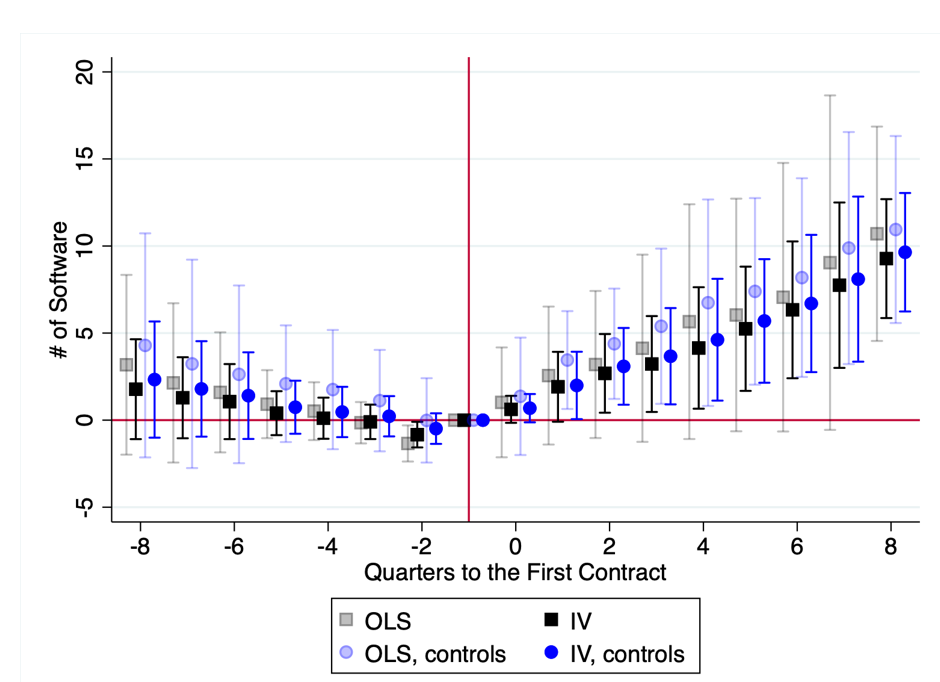

Having established that AI does strengthen autocrats' political control, we then examine the second direction in a mutually reinforcing relationship: whether politically motivated AI procurement stimulates AI software innovation (all Chinese firms’ software products are registered with China's Ministry of Industry and Information Technology). We study the effects of AI procurement contracts issued by local governments that experienced above median levels of political unrest in the preceding quarter, and find that a firm’s receipt of a politically motivated public security contract is followed by significantly greater innovation of software. This is seen not only for government software, but also for commercial software (identified using machine learning), suggesting that politically motivated contracts move the broader technological frontier, beyond simply generating products for government use. We find no evidence of differential pre-contract trends in software innovation, and our results are similar using local weather as an instrument for local political unrest, supporting a causal interpretation of our findings (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Software development by firms that receive public security contracts, relative to the time of receiving the initial contract.

Notes: Analysis restricted to firms that receive contracts in prefectures experiencing above-median political unrest in the previous quarter (IV analysis uses weather as an instrument to predict unrest).

Taken together, these results imply that China's autocratic political regime and the rapid innovation in its AI sector mutually reinforce each other. While a full-blown dystopian AI future may still exist only in science fiction, our evidence suggests that the foundations for AI innovation to foster autocracies around the globe already, in fact, exist.

References

Acemoglu, D (2021a). “Harms of AI,” Oxford Handbook of AI Governance.

Acemoglu, Daron (2021b). “Dangers of unregulated artificial intelligence,” VoxEU.

Aghion, P, B F Jones and C I Jones (2018), "Artificial intelligence and economic growth." In The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda, pp. 237-282. University of Chicago Press.

Agrawal, A, J Gans, and A Goldfarb (2018), Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

Beraja, M, A Kao, D Y Yang, and N Yuchtman (2023), “AI-tocracy,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

Beraja, M, David Y Yang and N Yuchtman (2023), “Data-intensive Innovation and the State: Evidence from AI Firms in China,” Review of Economic Studies, forthcoming.

Brynjolfsson, E, D Rock and C Syverson (2021), “The Productivity J- Curve: How Intangibles Complement General Purpose Technologies," American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 13(1): 333-72.

Bughin, J and E Hazan (2017), “The new spring of artificial intelligence: A few early economies,” VoxEU.

Schwab, K (2016), The Fourth Industrial Revolution. New York: Crown Business.

Tirole, J (2021), “Digital Dystopia,” American Economic Review, 111(6): 2007-2048.

Zuboff, S (2019), The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs.