Digital information campaigns on social media can be used to disseminate objective information about government performance and bolster electoral accountability. Targeting information at a larger share of the electorate can raise the effectiveness of these campaigns by amplifying social mechanisms of propagation.

The rapid spread of social media around the world has revolutionised citizens’ access to political information (Poushter et al. 2018, Zhuravskaya et al. 2020, Guriev et al. 2021). Social media enables powerful actors to misinform and manipulate citizens at scale. But it also offers unprecedented opportunities for citizens to hold elected politicians to account. To effectively harness the power of social media to enhance accountability, it is necessary to understand how different information dissemination strategies impact outcomes. Social media facilitates the rapid, low-cost distribution of information at high levels of ‘saturation,’ defined as the proportion of the electorate targeted directly by an information campaign.

Previous studies yield mixed results, suggesting that mass media information provision more strongly influences the voting behaviour of exposed citizens than in-person or small-scale dissemination (Ferraz and Finan 2008, Dunning et al. 2019, Dunning et al. 2019, Larreguy et al. 2020). However, little is yet known about the extent to which the level of saturation influences an information campaign’s effectiveness. To rigorously assess the causal effects of saturation on electoral accountability, we designed and conducted a nationwide field experiment in partnership with Borde Politico (Enríquez et al. 2024). Borde Politico’s Facebook ads exposed millions of Mexican citizens to the results of independent audits of their municipal government’s expenditures ahead of the 2018 elections. The research team randomised the level of information saturation experienced by each municipality.

Why might saturation matter for digital information campaigns?

We argue that providing information at high levels of saturation—that is, reaching a large share of the electorate—can promote electoral accountability more effectively than at low levels of saturation. Most obviously, higher saturation will increase the number of people exposed to the information both directly---because more people are directly targeted---and indirectly, as the information travels through social networks from those directly targeted to those not directly exposed. In addition, we argue that greater saturation will render any exposure to the information more powerful both for those directly and indirectly exposed, because high saturation activates mechanisms of social propagation and reinforcement that are not similarly activated under low saturation.

Specifically, high saturation can stimulate community discussion, intensifying information exposure and the salience of the discussed dimensions of incumbent performance (Iyengar and Kinder 1987), fostering political persuasion (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1955), facilitating belief updates regarding incumbent’s suitability for office, and/or enabling explicit or tacit voter coordination (Chwe 2000; Shadmehr and Bernhardt 2017). Moreover, high saturation can create common knowledge about citizens’ beliefs and voting intentions, amplifying information effects independently of direct communication (Arias et al. 2019, Cornand and Heinemann 2008, Morris and Shin 2002).

Experimentally measuring the role of saturation

Our field experiment evaluates the impact of a nonpartisan campaign by Borde Político—an NGO promoting government transparency in Mexico through digital tools—on voter turnout and vote choice. The campaign employed Facebook ads to inform citizens about the extent of irregularities in municipal expenditures identified by the Federal Auditor’s Office, Mexico’s nationwide independent government auditing body. The extent of irregularities varied widely, with approximately half of the municipalities exhibiting zero or negligible irregularities. This municipality-specific information was delivered through 26-second paid Facebook video ads during the week preceding the 2018 election, during which corruption was a major campaign issue. Our sample comprised 128 municipalities, each contesting incumbent party reelection.

We randomised the presence of the Facebook ad campaign at two levels. First, for each municipality in our sample, we randomised whether the Facebook ad campaign would target 0% (“control”), 20% (“low saturation”), or 80% (“high saturation”) of the electorate.

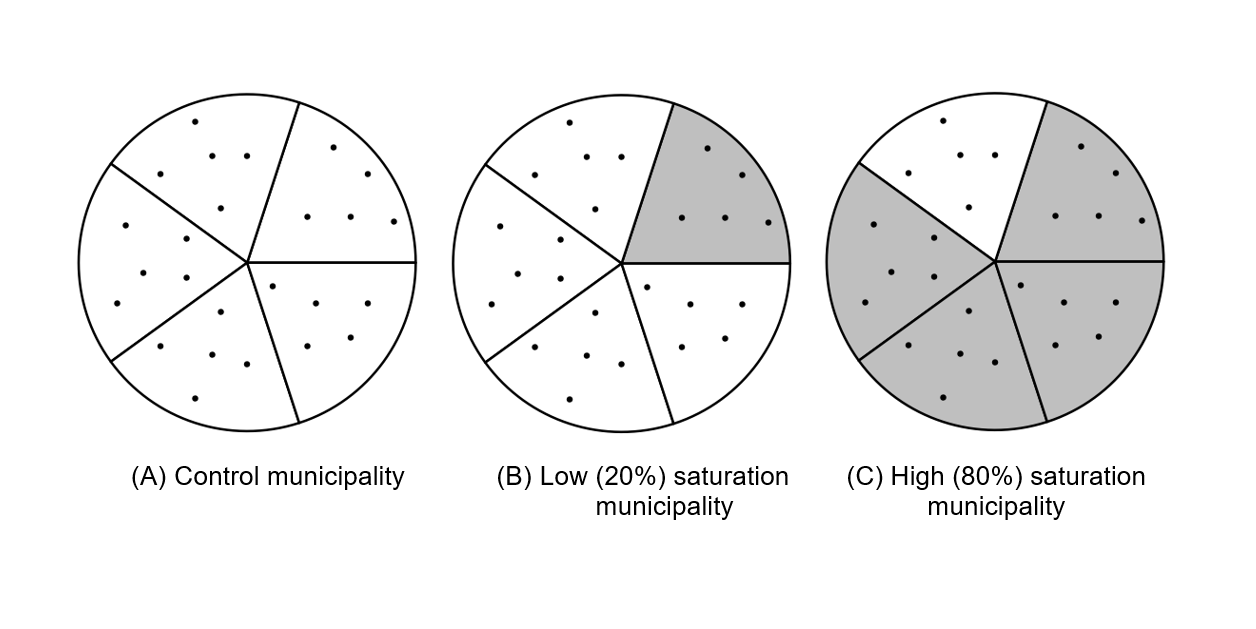

Second, we divided each municipality into multiples of 5 similarly sized geographical segments to vary the intensity of the campaign. In low saturation municipalities, 1 out of every 5 segments were randomly selected to receive ads. In high saturation municipalities, 4 out of every 5 segments were randomly selected to receive ads. Figure 1 illustrates the research design. Circles represent municipalities, pie slices denote segments, and dots indicate polling stations. Shaded segments received the Facebook ad treatment, while unshaded segments did not. Panels A-C illustrate municipalities assigned to control, low saturation, and high saturation, respectively.

Figure 1: Graphical illustration of randomised saturation design

Notes: Circles represent municipalities; pie slices indicate geographical segments; and dots denote polling stations. Shading denotes assignment to the Facebook ad campaign treatment.

Our design makes it possible to identify the direct and indirect effects of being targeted, as well as variation in both direct and indirect effects by the level of municipal saturation.

- Direct effects are estimated by comparing treated (shaded) segments in low or high saturation municipalities vs. segments in control municipalities.

- Indirect effects compare untreated (unshaded) segments within low or high saturation municipalities vs. untreated segments in control municipalities.

- Variation in direct effects by level of municipal saturation is estimated by comparing treated segments in low vs. high saturation municipalities

- Variation in indirect effects by level of municipal saturation is estimated by comparing untreated segments in low vs. high saturation municipalities,

Randomisation of treatment assignment ensures comparability across the different kinds of segments.

Key findings

1. The large-scale digital information campaign significantly increased electoral accountability.

This is most evident for what we call direct effects, meaning changes in vote choices in segments directly targeted with ads within treated municipalities. Specifically, the best-performing municipal incumbent parties—those with no or negligible irregularities—were rewarded by voters in segments targeted with ads with an extra 6-7 percentage point in vote share, compared to control municipalities. Conversely, poorly-performing municipal incumbent parties—those whose audits evidenced above-median levels of irregularities—exhibited reductions in the incumbent party’s vote share, although this effect was not statistically significant.

Indirect effects displayed a similar pattern but were roughly half the magnitude of direct effects and did not reach statistical significance. In contrast to vote choice, effects on voter turnout were minimal, increasing by only about 1 percentage point in directly targeted segments. This suggests that the observed vote choice effects resulted primarily from vote switching rather than from turnout-enhancing mobilisation.

2. The electoral impact of the information campaign was strongly moderated by saturation levels.

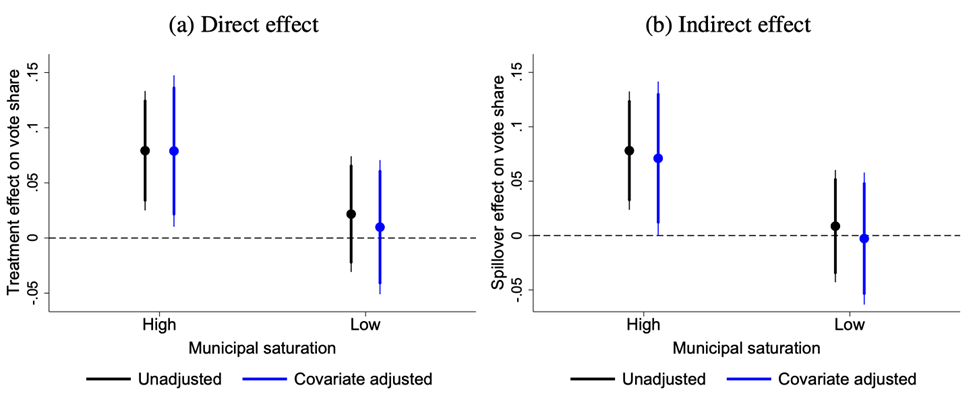

Figure 2 displays the differential effects of directly or indirectly receiving the Facebook ad campaign by level of municipal saturation. Panel (a) shows that in directly treated segments within high saturation municipalities (80% of the electorate targeted), the best-performing incumbents (those with zero or close to zero irregularities) were rewarded with an additional 7-8 percentage points in party vote share. In contrast, in low saturation municipalities (20% targeted), the best performing parties received only 2-3 percentage points extra vote share in directly treated segments.

Furthermore, panel (b) shows that indirect effects were nearly as large as direct effects in high saturation municipalities, but negligible in low saturation ones. In other words, high saturation not only increases information dissemination—a mechanical consequence of targeting a larger share of an electorate—but it also amplifies the information campaign’s effectiveness for both directly and indirectly exposed individuals.

Figure 2: Conditional average treatment effects of Facebook ad campaign on incumbent party vote share in municipalities with below-median irregularities, by information campaign saturation

Notes: High saturation indicates that 4 out of every 5 segments in the municipality were assigned to exposure to the Facebook ad campaign, while low saturation indicates that 1 out of every 5 segments were thus assigned. Details of the regression specifications can be found in Enríquez et al. (2024). Thick and thin lines denote 90% and 95% confidence intervals, respectively.

Our evidence suggests that high saturation facilitated social propagation mechanisms. First, substantial spillover effects on untreated segments within high-saturation municipalities suggests that factors beyond direct ad exposure accounted for a large proportion of the information campaign’s effects. Second, we find that electoral rewards for the best-performing municipal governments were greater in municipalities where individuals were more likely to be “friends” on Facebook, a possible catalyst of online or offline political discussion and coordination between citizens. Finally, we find no evidence that non-social propagation mechanisms, such as reactions from politicians or traditional media, influenced the outcomes in our study context.

The fight back against misinformation

Amid global concerns regarding social media’s role in disseminating politically relevant misinformation, polarising electorates, and eroding trust in democracy, our findings demonstrate that non-partisan organisations can also harness social media to enhance electoral accountability. Our study suggests that low-cost social media interventions can buttress democratic accountability. This is particularly important in the Global South, where social media usage continues to grow rapidly, and significant governance challenges remain.

Future research should further elucidate how the saturation of digital information campaigns moderates or drives the role of mass media in promoting or hindering electoral accountability. Finer-grained distinctions between the mechanisms shaping voter responses, such as belief updating, priming, or tacit and explicit coordination, would be valuable, especially for optimising the impact of non-partisan social media campaigns.

Our findings emphasise the crucial role of saturation in determining the effectiveness of digital information campaigns aimed at enhancing electoral accountability. However, our results also suggest that high-saturation dissemination could amplify the impact of misinformation as well as that of accurate information. This dual potential suggests that policymakers and regulators should consider harnessing social media's capacity for high-saturation dissemination of verifiable, non-partisan information while mitigating the risks associated with misinformation. For instance, electoral commissions or transparency agencies could collaborate with social media platforms to promote widespread access to verified information about government performance. Regulations might incentivise or mandate platforms to facilitate such campaigns—perhaps by offering reduced advertising rates for certified non-partisan content or by establishing dedicated channels for public service announcements. Nonetheless, policy choices about high-saturation campaigns may depend on the expected balance between beneficial and harmful content online. It is therefore important to implement stringent measures against the spread of misinformation.

References

Arias, E, P Balán, H Larreguy, J Marshall, and P Querubín (2019), “Information provision, voter coordination, and electoral accountability: Evidence from Mexican social networks,” American Political Science Review, 113(2): 475–498.

Chwe, M S (2000), “Communication and coordination in social networks,” The Review of Economic Studies, 67(1): 1–16.

Cornand, C, and F Heinemann (2008), “Optimal degree of public information dissemination,” The Economic Journal, 118(528): 718–742.

Dunning, T, G Grossman, M Humphreys, S D Hyde, C McIntosh, G Nellis, C L Adida et al. (2019), “Voter information campaigns and political accountability: Cumulative findings from a preregistered meta-analysis of coordinated trials,” Science Advances, 5(7): eaaw2612.

Dunning, T, C Bicalho, A Chowdhury, G Grossman, M Humphreys, S D Hyde, C McIntosh, and G Nellis (2019), “Meta-analysis,” in Information, Accountability, and Cumulative Learning: Lessons from Metaketa I, New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 315–374.

Enríquez, J R, H Larreguy, J Marshall, and A Simpser (2024), “Mass political information on social media: Facebook ads, electorate saturation, and electoral accountability in Mexico,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 22(4): 1678–1722. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvae011.

Ferraz, C, and F Finan (2008), “Exposing corrupt politicians: The effects of Brazil's publicly released audits on electoral outcomes,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2): 703–745.

Guriev, S, N Melnikov, and E Zhuravskaya (2021), “3G internet and confidence in government,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(4): 2533–2613.

Iyengar, S, and D R Kinder (2010), News that matters: Television and American opinion, University of Chicago Press.

Katz, E, and P Lazarsfeld (1955), “Interpersonal networks: Communicating within the group,” in Personal Influence, New York: Free Press.

Larreguy, H, J Marshall, and J M Snyder Jr. (2020), “Publicising malfeasance: When the local media structure facilitates electoral accountability in Mexico,” The Economic Journal, 130(631): 2291–2327.

Morris, S, and H S Shin (2002), “Social value of public information,” American Economic Review, 92(5): 1521–1534.

Poushter, J, C Bishop, and H Chwe (2018), “Social media use continues to rise in developing countries but plateaus across developed ones,” Pew Research Center, 22: 2–19.

Shadmehr, M, and D Bernhardt (2017), “When can citizen communication hinder successful revolution,” Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 12(3): 301–323.

Zhuravskaya, E, M Petrova, and R Enikolopov (2020), “Political effects of the internet and social media,” Annual Review of Economics, 12(1): 415–438.