Chinese development projects have increased popular support for the Chinese government in the Global South

Editor's note: This article originally appeared on VoxEU.

As relations between China and the US and other Western democracies deteriorate, the Global South is becoming an increasingly important arena for great power competition. Policymakers in Washington, London, and Brussels have repeatedly sounded alarm bells regarding the nature, motives, and effects of Chinese aid and lending in developing countries (Reinhart et al. 2020, Tierney et al. 2019, Dreher and Fuchs 2012). During an official visit in August 2023, for instance, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken warned his Tongan counterparts of China’s “problematic behaviour” including “predatory economic activities” and “investments that are done in a way that can actually undermine good governance and promote corruption” (US Department of State 2023). His comments reflect a broader struggle between the US and China to effectively control narratives about their development finance and win popular support across Asia, Africa, and other developing regions.

Aid as a tool of soft power

The pursuit of ‘soft power’ is an important objective for powerful countries like the US and China. As Goldsmith et al. (2014: 88) point out, “competition between major powers such as the United States and China for favourable perceptions in global public opinion is increasingly evident today and likely to be a pivotal feature of the emerging international order.” In a world of increasing geo-economic fragmentation, soft power – “the ability to achieve goals through attraction rather than coercion” (Nye 2004: x) – has become a highly coveted asset. Soft power can strengthen a country’s geopolitical position by expanding support for its foreign policies and boosting its exports (Goldsmith and Horiuchi 2012, Guiso et al. 2009, Rose 2016, 2018).

For these reasons, donors and lenders have long used foreign aid to shape public perceptions in developing countries. They invest a considerable amount of time and money disseminating positive messages about their generosity to members of the public. They place signage at project sites to inform the public of their activities. They organise public ceremonies to mark the start of new projects and the completion of existing ones. Some even broadcast their own messages through social media channels and cultivate journalists to encourage media coverage of their accomplishments. ‘Brand management’ is one of the most important reasons why donor governments extend foreign aid bilaterally rather than multilaterally. Yet there is little systematic evidence on whether and to what extent international development finance increases popular support for donor governments. This evidence gap is particularly glaring for China, which is now the largest bilateral source of development finance in the world.

Whether aid bolsters or erodes support for donor governments abroad is a longstanding question. Instead of increasing support for donor governments, development projects might backfire if they are not carefully designed and implemented, disproportionately benefit elites and vested interest groups rather than the general public, or otherwise fail to meet the expectations of local communities. Infrastructure and other projects that involve large-scale construction activities often create significant economic opportunities, but they also produce noise, traffic, and pollution. In the absence of strong managerial oversight, they can lead to labour strikes, public protests, lawsuits, and allegations of political favoritism or corruption.

Chinese development finance provides a useful and important setting in which to examine the potential effects of development projects on host country attitudes toward donors and lenders. In recent years, the Chinese government has become the world's largest bilateral source of international development finance, outspending the US on a more than two-to-one basis in the years before the COVID-19 pandemic (Malik et al. 2021). As an emerging power, China is increasingly seeking to expand its economic and political influence around the world. Beijing understands that development finance is an important tool for doing so and it has actively used aid and credit to burnish its popular image and secure support from foreign governments for decades. In 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping acknowledged that the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is part of a broader effort to “increase China’s soft power, give a good Chinese narrative, and better communicate China’s message to the world'' (People’s Daily 2014). Chinese development projects are undertaken in the service of this larger objective. They usually involve ground-breaking and ribbon-cutting ceremonies that attract public attention and drive local and international media coverage.

The effect of projects on public support for Beijing

In a recent paper (Wellner et al. 2023), we test the effectiveness of China’s overseas development program as a soft power instrument. We use data from 1.5 million individuals across 126 countries who participated in the Gallup World Poll between the 2006 and 2017 period and answered a question about approval or disapproval of the Chinese government. Our approach builds on earlier literature that measures soft power using recipient country public opinion toward governments (Nye 2004, Goldsmith and Horiuchi 2012, Rose 2016). We distinguish between the short-term and longer-term effects of aid projects on public support for Beijing.

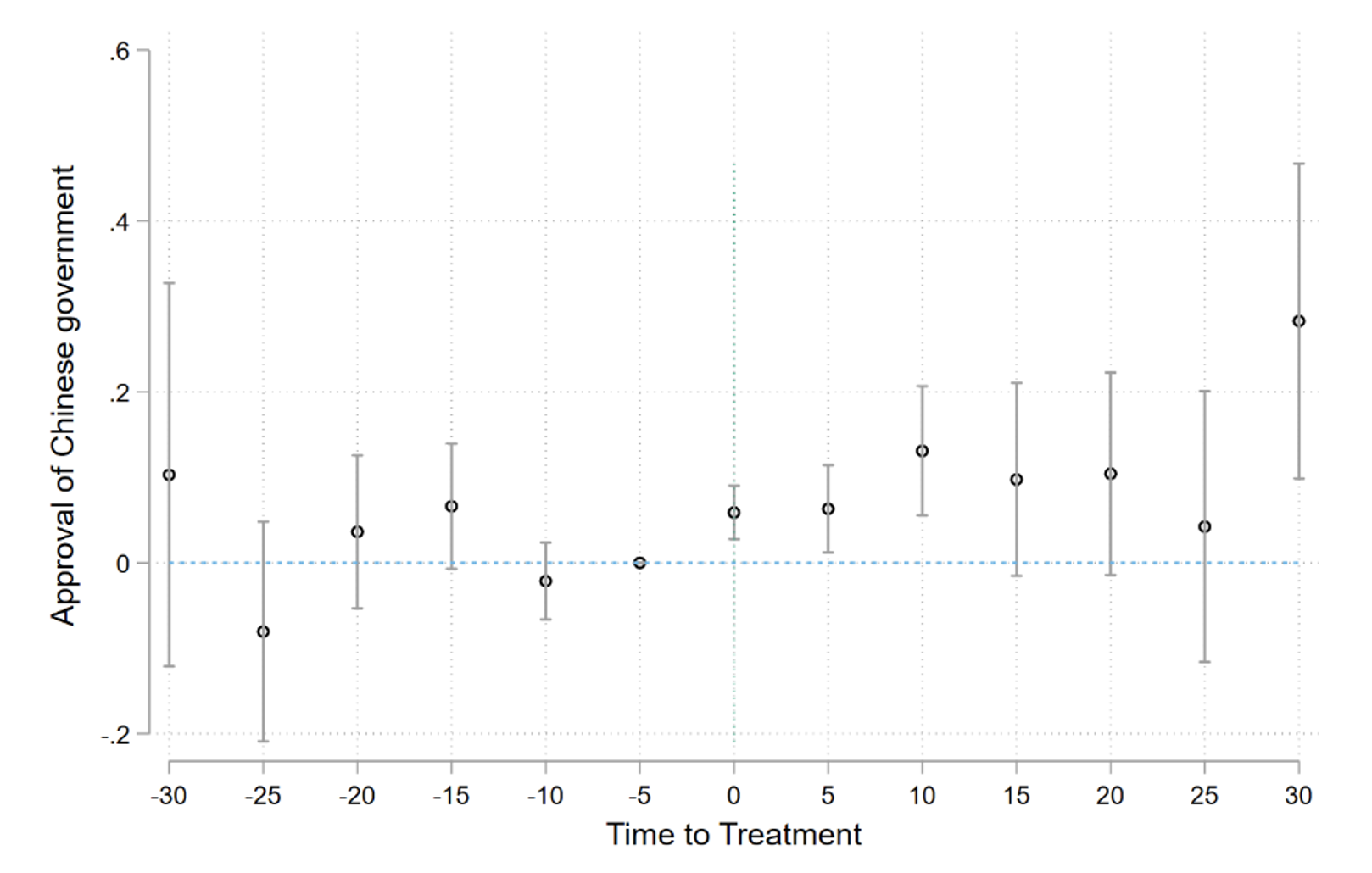

In the short-term analysis, we examine the effect of project-specific events – project announcements, ground breakings, and completion ceremonies – on public approval of the Chinese government. To do so, we created a new dataset including 3,998 commitment, start, and end dates of 2,214 Chinese development projects found in the 1.1.1 version of AidData’s Global Chinese Official Finance Dataset (Dreher et al. 2021, 2022). The staggered rollout of the Gallup World Poll over an average period of four weeks allows us to compare individuals interviewed just before a project event to those interviewed just after it. In combination with individual- and survey-level controls, this approach allows us to draw causal conclusions. Our findings suggest that the completion of Chinese development projects increases public approval of the Chinese government in recipient countries by around three percentage points. As Figure 1 demonstrates, there is no anticipation effect prior to project completion. We also find that the effect is stronger for larger projects and those financed on generous terms. Another important finding is that the effect is not limited to individuals located in communities near projects; it applies broadly to individuals located throughout the recipient country.

Figure 1 Completion of Chinese projects and support for the Chinese government, event study plot

Notes: The figure displays the coefficients and the 90 percent confidence intervals for 13 binary variables indicating 5-day blocks from 30 days before to 30 days after a Chinese project event. The coefficient for the period between 5 to 1 days before the event is normalized to 0. Source: Wellner et al. (2023).

We then aggregate China’s overseas development projects to the province and country levels to identify the potentially longer-term effects of project completion on Chinese government approval. We examine this outcome for provinces, entire countries, and at the global level. Our instrumental-variables approach is based on Bluhm et al. (2020) and Dreher et al. (2021) and makes use of a supply shock – the yearly production volumes of physical construction materials produced in China – to proxy for the availability of Chinese development projects each year. Chinese grant- and loan-financed development projects are often tied to goods and services provided by Chinese companies, and as such, project implementation relies heavily on surplus input materials produced in China. Intuitively, larger production volumes of construction materials in China should increase the overall supply of overseas development projects. We interact this measure with the ‘probability of receiving aid from China’ – i.e. the share of years over the sample period in which a province received a development project from China – to proxy for which provinces are more likely to receive larger or smaller shares of additional projects that result from these supply shocks.

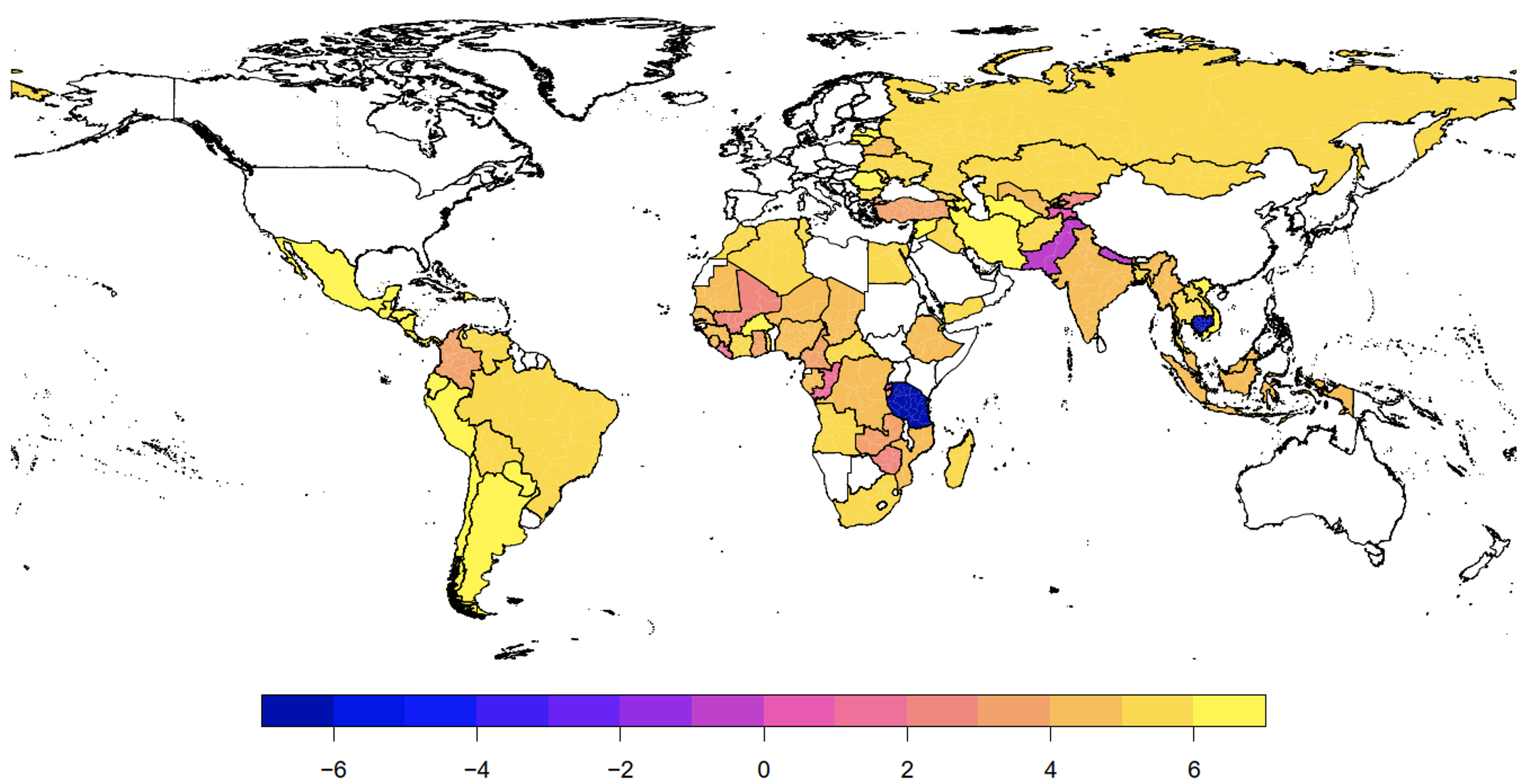

The results again show a positive effect of project completion on popular support for the Chinese government in recipient countries. One additional Chinese development project increases public approval for the Chinese government in the recipient country by 0.2 percentage points (with slightly lower effects in project provinces). Figure 2 presents a ‘what if’ scenario in which the Chinese government equally distributes all projects across all countries, leading to a hypothetical inflow of 30 projects over our sample period. The results summarized in the global map highlight the significance of China’s soft power gains through its overseas development program and its potential to further expand support in thus far neglected regions. By way of illustration, consider Cambodia. If it had received 30 Chinese development projects rather than the 91 that it actually received, our statistical model indicates that Beijing would have suffered a 12.55 percentage point loss of public support in that country. Additional tests suggest that the observed effects on international public opinion are driven by higher incomes and increased satisfaction with public services in recipient countries.

Figure 2 Counterfactual: Equal distribution of Chinese projects and approval of the Chinese government

Notes: The figure displays the percentage-point change in public approval of the Chinese government if Chinese projects would have been distributed equally across all countries in the sample, providing 30 projects per country. Brighter colours signify an increase in approval of the Chinese government, darker colours a decrease in approval of the Chinese government. Support for the Chinese government would erode in countries that receive many Chinese projects, such as Tanzania (-16 pp) or Cambodia (-13 pp), whereas approval of the Chinese government would be strengthened in regions with little or no Chinese development finance activity.

Conclusion

One of the main takeaways of our study is that understanding the link between aid and soft power requires accounting for different levels of analysis. The public opinion effects of development projects are not necessarily limited to the localities where these projects occur. Aid branding and publicity can affect attitudes in farther-flung places, too, and attitudinal effects in some places can offset effects in others.

Our findings also show that Chinese development projects have not uniformly increased popular support for the Chinese government in the Global South. Beijing managed to sway public sentiment in important subsets of recipient countries. Specifically, we find that China’s provision of development projects boosted approval for the Chinese government among arguably ‘high-value’ targets for Beijing. These include countries in Africa, ‘swing states’ in the United Nations General Assembly (i.e. those that are neither in the US nor in the Chinese ‘camp’ but tend to switch sides), and countries with higher baseline levels of public support for the Chinese government.

On balance, our results suggest that Chinese development projects can positively impact public approval of the Chinese government, particularly in strategically important countries. The US and partner countries are increasingly anxious about China’s pursuit of global influence, including its efforts to win hearts and minds in the Global South by building development projects. Our findings suggest that their concerns are well-founded.

References

Bluhm, R, A Dreher, A Fuchs, B Parks, A M Strange and M J Tierney (2020), “Connective Financing: Chinese Infrastructure Projects and the Diffusion of Economic Activity in Developing Countries”, CEPR Discussion Paper 14818.

Dreher, A and A Fuchs (2012), “Rogue aid? On the importance of political institutions and natural resources for China’s allocation of foreign aid”, VoxEU.org, 27 January.

Dreher, A, A Fuchs, B C Parks,, A Strange and M J Tierney (2021), “Aid, China, and Growth: Evidence from a New Global Development Finance Dataset”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13(2): 135-174.

Dreher, A, A Fuchs, B C Parks, A Strange and M J Tierney (2022), Banking on Beijing. The Aims and Impacts of China’s Overseas Development Program, Cambridge University Press.

Dreher, A, A Fuchs, R Hodler, B C Parks, P A Raschky and M J Tierney (2021), “Is Favoritism a Threat to Chinese Aid Effectiveness? A Subnational Analysis of Chinese Development Projects”, World Development 139, 105291.

Goldsmith, B E and Y Horiuchi (2012), “In Search of Soft Power: Does Foreign Public Opinion Matter for US Foreign Policy?”, World Politics 64(3): 555–585.

Goldsmith, B E, Y Horiuchi and T Wood (2014), “Doing Well by Doing Good: The Impact of Foreign Aid on Foreign Public Opinion”, Quarterly Journal of Political Science 9(1): 87–114.

Guiso, L, P Sapienza and L Zingales (2009), “Cultural Biases in Economic Exchange?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(3): 1095–1131.

Malik, A A, B Parks, B Russell, J J Lin, K Walsh, K Solomon, S Zhang, T B Elston and S Goodman (2021), “Banking on the Belt and Road: Insights from a New Global Dataset of 13,427 Chinese Development Projects”, AidData at William & Mary.

Nye, J S (2004), Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics, Public Affairs.

People’s Daily (2014), “Xi Eyes More Enabling Int’l Environment for China’s Peaceful Development”, 30 November.

Reinhart, C, C Trebesch and S Horn (2020), “China’s overseas lending and the looming developing country debt crisis”, VoxEU.org, 4 May.

Rose, A K (2016), “Like Me, Buy Me: The Effect of Soft Power on Exports”, Economics & Politics 28(2): 216-232.

Rose, A K (2018), “The economic cost of repellent leadership: Losing soft power lowers exports”, VoxEU.org, 18 September.

Tierney, M, P Raschky, B Parks, R Hodler, A Fuchs and A Dreher (2019), “Political bias and the economic impact of Chinese aid”, VoxEU.org, 7 October.

US Department of State (2023), "Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Tongan Prime Minister Hu’akavameiliku at a Joint Press Availability", US Department of State Press Release, 26 July.

Wellner, L, A Dreher, A Fuchs, B Parks, A Strange (2023), “Can Aid Buy Foreign Public Support? Evidence from Chinese Development Finance”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, forthcoming.