Welfare programmes, even when designed to prevent misuse, can be subverted by a political party and may encourage the centralisation of corruption.

Anti-poverty programmes have historically been plagued by corruption, mismanagement, or the politicisation of benefits (Bardhan and Mookherjee 2006, Cole 2009, Muralidharan et al. 2021). Newer programmes are designed to prevent this through checks and balances that disperse power across key stakeholders. The goal is to make it impossible for a sole actor to capture the entire programme and ensure that there is no incentive for other actors to participate in such misuse.

Strong political organisations can subvert checks and balances on welfare programmes

In the presence of strong political organisations, dispersion of power may be insufficient to prevent capture. A political organisation may coordinate veto-holders towards circumventing checks and balances. If it succeeds it can subvert government resources to finance its own operations in ways unavailable to opponents who control fewer offices. It may exploit its competitive advantage to ultimately deepen and broaden the number of offices it controls. We study how a political organisation can build such a system (Shenoy and Zimmermann 2024).

Who controls the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act in India?

The context of our study is West Bengal, an Indian state of 90 million residents. We study how its ruling party exploited state and local control over a massive make-work scheme, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA), to consolidate and grow its power. The initial programme design of NREGA was heavily shaped by technocratic and social activist non-government forces, with financial and implementation powers carefully dispersed across multiple levels of government and the broader public to prevent corruption (Dey and Drèze 2004). In practice, the national government provides most of the funding for the programme, but the state government ultimately controls which local governments receive NREGA projects. Local councils, in turn, control the allocation of NREGA jobs to villagers within their jurisdiction (called the gram panchayat, or panchayat for short) (Dutta et al. 2012, Government of India 2005). This dispersion of power creates complementarities between control of the state and local governments.

State and local control lead to higher welfare allocations that drive ‘vertical’ expansion of power

West Bengal’s ruling party, the AITC (All-India Trinamool Congress) first took control of the state government in 2011 and we trace the party’s expansion of power over the next seven years. It won absolute majorities in many local councils in 2013, giving it power over both complementary levels of government needed to control NREGA allocations. We exploit quasi-random variation created by barely-won majorities in this local election to study the impact of complementary control.

We observe how the majority party exploits its multi-level control of NREGA by scraping and compiling administrative records for 300 million NREGA payments made to named individuals spread across an eligible pool of 11 million households. We combine these records with data on the thousands of candidates contesting the 2013 local council elections and polling station-level data on vote returns for the 2014 national election. We leverage this unique dataset to study programme allocations across and within gram panchayats.

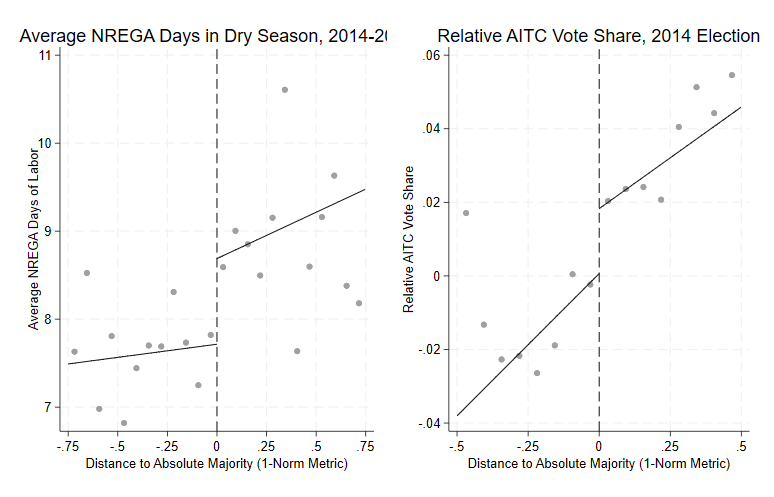

The left part of Figure 1 shows that having the absolute majority in the local council (to the right of the dashed line), which gives the state ruling party full control over two levels of government, lead to higher NREGA allocations to these panchayats during the dry season. Demand for jobs during this agricultural off-season is particularly sought after, so households in areas where the ruling party is in power locally get extra welfare benefits which similar households in panchayats ruled by the political opposition do not receive.

The right part of Figure 1 reveals that these areas where the ruling party is in power locally returned more votes for the state ruling party in the national election of 2014. These additional votes contributed to the party’s massive ‘vertical’ expansion of power into the national legislature. It won almost all seats in West Bengal, establishing its dominance in a third tier of government.

Figure 1: Impact of controlling local government on NREGA days and national votes

Why would sending more funds to areas under the control of local co-partisans lead to more votes?

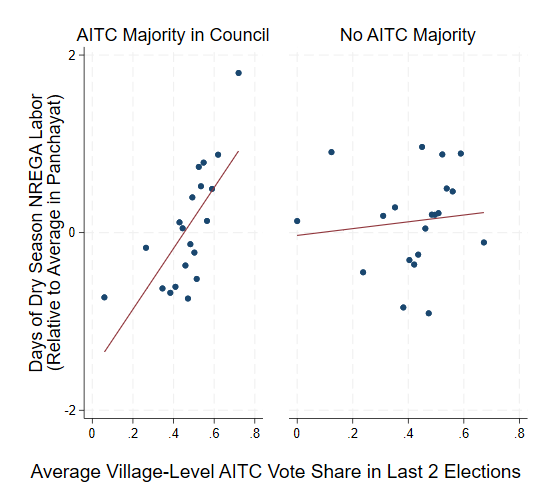

One possibility is that local co-partisans may deliver benefits with strings attached, rather than to voters who most need the support. We find that panchayats controlled by the ruling party are no more likely to give jobs to voters from disadvantaged castes, religious minorities, or who hold below-poverty-line status. The voters who do get extra jobs are those in areas that have historically supported the ruling party. A typical panchayat in West Bengal administers 5 to 20 villages. Figure 2 shows that there is a strong positive correlation between the historical support of a village for the AITC and the quantity of NREGA labour received in the dry season before the 2014 national election. This pattern is absent in panchayats not controlled by the ruling party. It is consistent with an explicit or implicit quid pro quo where loyal supporters are rewarded for turning out (Hicken 2011, Stokes et al. 2013).

Figure 2: Electoral support and NREGA

Reallocating money to align the interests of local politicians with those of the party

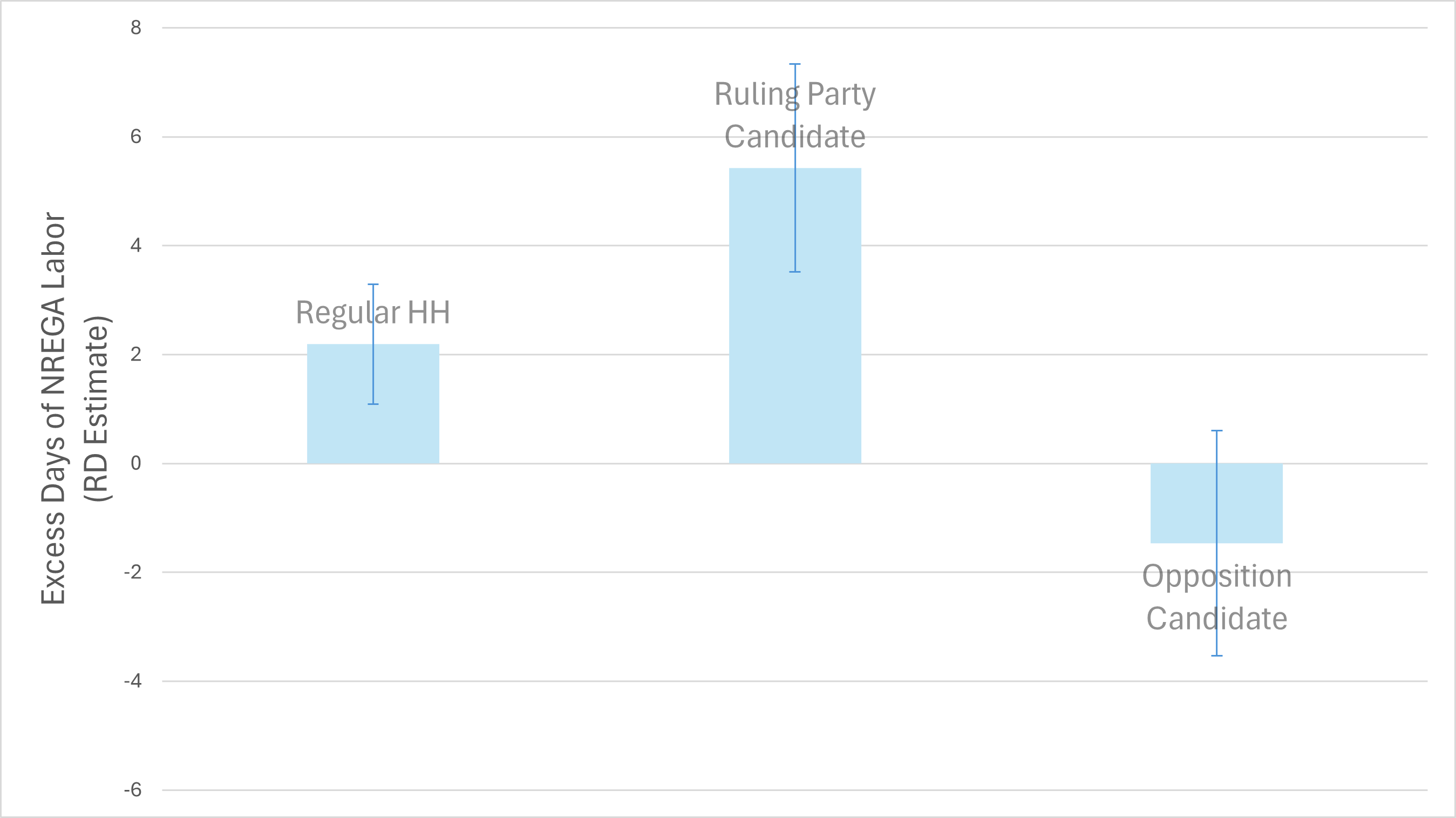

How was the ruling party able to motivate local politicians to target funds on behalf of national co-partisan candidates who have no statutory authority over them? Through additional NREGA funds that directly go into local politicians’ bank accounts, as we show in Figure 3. Political candidates of the AITC in panchayats where it controls the local council receive about two and a half times the NREGA benefits of regular households in their area, which are already higher than those in opposition-ruled areas. Opposition candidates, on the other hand, are systematically punished with fewer NREGA days. Ruling party candidates therefore benefit financially from loyalty to their party.

Figure 3: Excess NREGA employment for ruling party candidates relative to regular households and opposition candidates

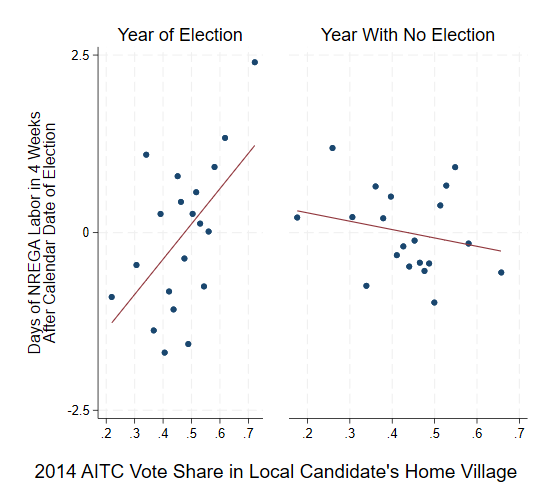

In addition to these constant payments, local politicians also receive incentive payments for successful voter mobilisation in election years. Figure 4 shows that in panchayats where the AITC holds a majority in the council, there is a strong positive correlation between the extra NREGA days a local politician receives and the number of votes his village delivers to the ruling party during the 2014 national election. This pattern only appears in election years, implying it is tied to the election and not an artifact of the time of year when elections typically happen.

Figure 4: Extra NREGA days for local politicians who deliver votes in an election

The ruling party also expands 'horizontally' into opposition areas

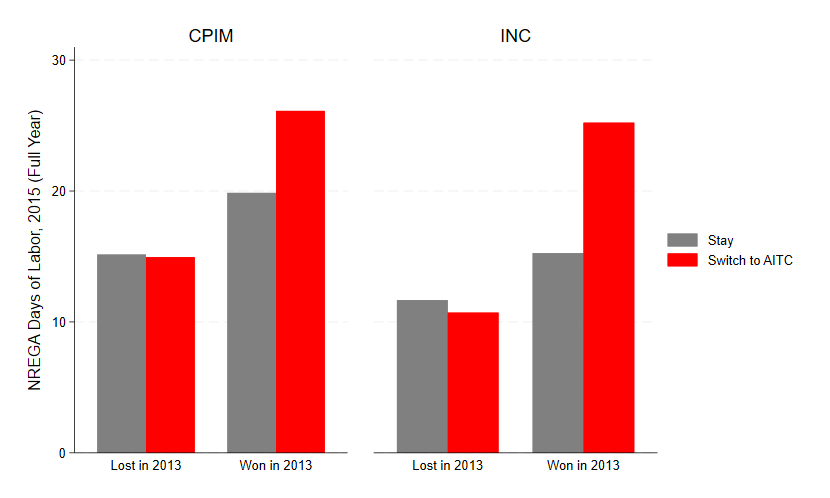

In addition to the vertical expansion of power, the AITC also recruited opposition councilors in local governments in the following years where it originally failed to win a majority, thereby expanding its power ‘horizontally’. Figure 5 suggests that NREGA payments were a crucial tool to encourage party switching among capable candidates from the two main opposition parties (CPIM and INC). NREGA payments are higher for politicians who switch to the AITC, but only among those who are current office holders in local councils because they won their races in 2013.

Figure 5: NREGA employment of opposition candidates by own electoral success and party loyalty

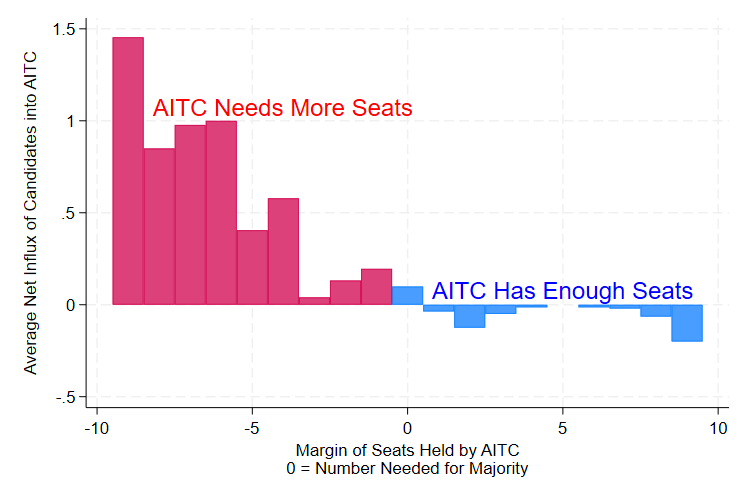

Figure 6 further makes clear that the AITC very deliberately chooses who can join the ruling party: the influx of opposition candidates only happens in areas where the AITC needs more seats to gain the majority, not in councils where it is already in control.

Figure 6: Party switching only in areas where it helps the state incumbent party

Implications for safeguarding welfare programmes from corrupt politicians

This AITC system of expanding control over multiple tiers of government is therefore able to circumvent the checks and balances embedded in the NREGA programme and use welfare funds for the political gain of the party organisation. While it takes a strong party organisation to centralise power in this way, the dispersion of NREGA programme powers may ironically create the incentives for centralised corruption through complementarities of power in the first place.

This has implications for the optimal design of welfare programmes, where fresh ideas are needed to ensure that programme benefits accrue to eligible households equally. Failing to do so may undermine democracy by massively tilting the playing field in favour of the incumbent government.

References

Bardhan, P and D Mookherjee (2006), “Pro-Poor Targeting and Accountability of Local Governments in West Bengal,” Journal of Development Economics, 79 (2), 303–327.

Cole, S (2009), “Fixing Market Failures or Fixing Elections? Agricultural Credit in India,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(1): 219–250.

Dey, N and J Drèze (2004), “Employment Guarantee Act - A Primer”.

Dutta, P, Murgai, R, Ravallion, M and D van de Walle (2012), “Does India’s Employment Guarantee Scheme Guarantee Enployment?,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6003.

Government of India (2005), “The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act”.

Hicken, A (2011), “Clientelism”, Annual Review of Political Science, 14, 289-310.

Muralidharan, M, Niehaus, P, Sukhtankar, S and J Weaver (2022), Improving Last-Mile Service Delivery Using Phone-Based Monitoring: Evidence from India, VoxDev, available here.

Shenoy, A and L V Zimmermann (2024), “Political Organizations and Political Scope”, Working Paper.

Stokes, S, Dunning, T, Nazareno, M and V Brusco (2013), “Brokers, Voters, and Clientelism: The Puzzle of Distributive Politics”,