Government use of prison labour can distort incentives for incarceration and have lasting negative effects on trust in legal institutions like police

There are more people incarcerated today than at any other point in human history, with the current prison population estimated at around 11 million globally (World Prison Brief 2020). As the incarceration rates rise around the world, the policy discussion has turned to what to do with the large reserves of incarcerated people (Jacobson et al. 2017).

Many government leaders, from the US to China and Tanzania (Campbell 2020, Doston and Vanfleet 2014, BBC 2018), have suggested prison labour as an efficient means of maintaining the growing number of incarcerated people. Government proponents have also emphasised the potential to realise economic gains from a workforce of virtually ‘free labour’ (BBC 2018).

But what are the effects on incarceration when prisoners are viewed and used as a source of labour to serve the state’s economic interests? And what are the potential implications for citizens’ views of state legitimacy when an institution of state justice, like prisons, is used to serve economic or extrajudicial interests?

Evidence from colonial Nigeria

In a new study, we answer these questions using evidence from British colonial Nigeria over 1920 to 1959, where prison labour was a major feature of state policy and finance (Archibong and Obikili 2020).

As part of official colonial policy, prison labour on government public works was a mandated part of incarceration. Unpaid prison labour was essential in meeting government labour demands for construction and maintenance of central revenue generating public works. This is not the case in postcolonial Nigeria, beginning in 1960, where prison labour is not a major feature of state finance.

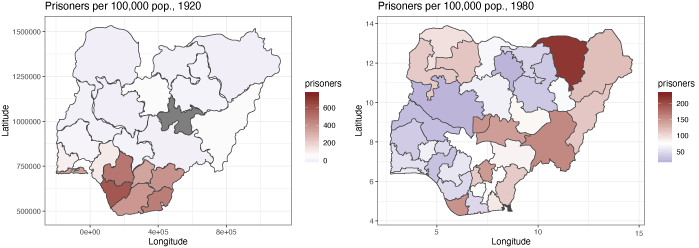

These differences between government use of prison labour in the colonial and postcolonial period are reflected in the spatial distribution of incarceration rates, as highlighted in Figure 1. Importantly, such differences allow us to answer key questions about the effects of prison labour. We digitised 65 years of archival records on prisons from 1920 to 1995, and provide new estimates on the value of prison labour and the effects of labour demand shocks on incarceration in Nigeria.

Figure 1 Prison population in colonial (1920) and postcolonial (1980) Nigeria

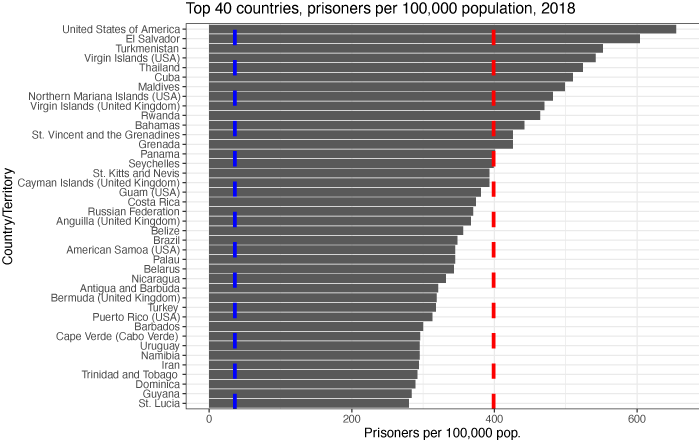

Colonial Nigeria is an informative region to study these questions, given its relatively high incarceration rates. If compared with contemporary data, colonial Nigeria’s incarceration rate in 1940 would have ranked it at number 15 of 222 countries, as shown in Figure 2. Nigeria’s incarceration rates are much lower today, with the country ranking at 211 of 222 by World Prison Brief estimates.

Figure 2 Top 40 countries/territories for incarceration rates, 2018, with Nigeria incarceration rates in red (year 1940) and blue (year 2018)

Source: World Prison Brief (2020)

Why was the British colonial government incarcerating so many people in Nigeria?

Prison labour was a small part of a larger regime of domestic forced labour in colonial Africa. Prisoners were required to work as punishment for crimes, as defined by governments. Their unpaid labour was viewed as a source of cheap labour for government public works projects.

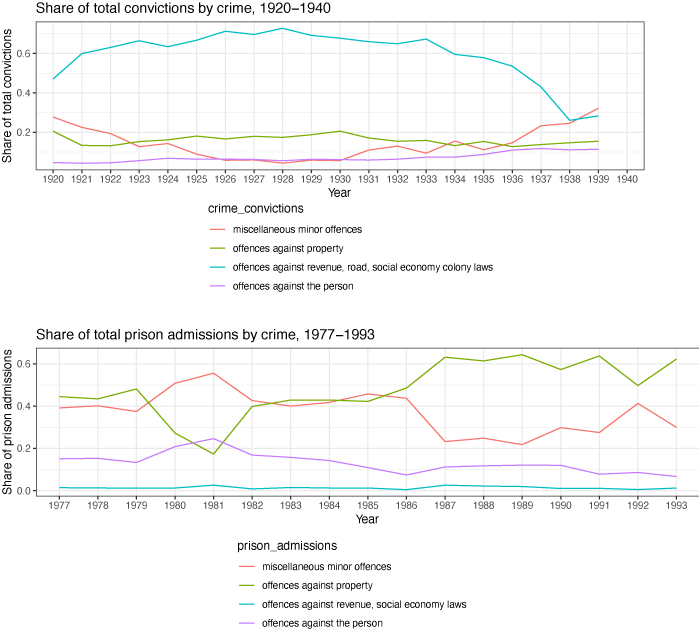

Colonial governments could address fiscal pressures and labour shortages by adjusting punishments for crimes as needed (Branch 2005). Figure 3 illustrates this — more than 50% of convictions in colonial courts were for rather nebulous “offences against revenue laws, municipal, road and other laws relating to the social economy of the colony.” In contrast, during the postcolonial period, people are mostly incarcerated for property crimes.

Figure 3 Share of total convictions in colonial courts and share of total prison admissions in postcolonial period by crime in Nigeria, 1920-1993

We assess the importance of prison labour to the colonial regime by first calculating the value of unpaid prison labour, and then estimating its share in colonial public works expenditures. We measure the overall value of prison labour as the amount of unpaid wages to prison workers.

Our results show that prison labour was economically valuable to the British colonial government. The gross value of prison labour was strictly positive over the entire colonial period. Even when we account for the most expansive set of prisoner maintenance costs, the net value of prison labour is strictly positive in around 60% of the years from 1920 to 1959 in Nigeria. The share of the overall prison labour in colonial public works expenditure ranged between 40% and 249%.

Given how valuable prison labour was to the colonial government, what happened to the demand for convict labour when there were sudden increases in labour demand? One way to answer this question is to analyse the effect of rising agriculture productivity.

Positive economic shocks and prison labour

Improving agriculture productivity largely drove increases in labour demand. Such improvements intensified the need for construction and maintenance of railroads, in order that agricultural commodities were exported. We construct two measures of shocks to agricultural productivity: (1) rainfall shocks based on district level rainfall deviations in a primarily agricultural setting, (2) export cash crop prices and district level crop suitability.

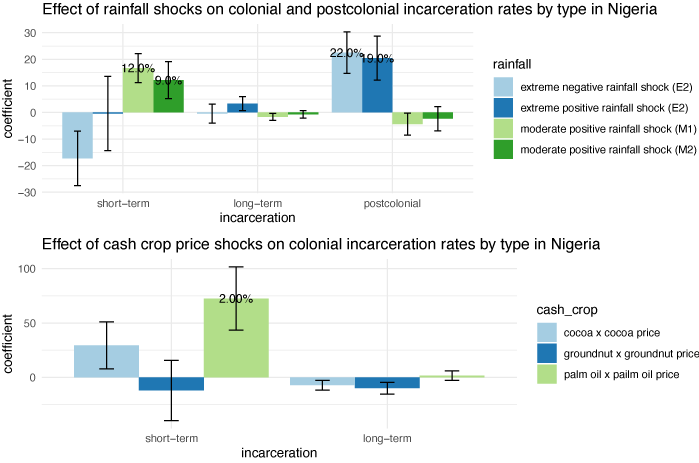

Our main results, depicted in Figure 4, show that incarceration rates were procyclical during the colonial period. We identify positive economic shocks as moderate rainfall shocks (M) that raised agricultural productivity, and increases in the export prices of relatively high value cash crops like palm oil. We find that these positive shocks increased colonial incarceration rates and the use of prison labour.

The positive effect is specific to short-term incarceration rates only. Temporary shocks increased the share of prisoners with sentences less than six months, but with no effect on the incarceration rates of long-term prisoners with sentences greater than two years, as shown in Figure 4. Moderate positive rainfall shocks increased short-term incarceration rates by almost 17 prisoners per 100,000 population, a 12% increase relative to a mean of 135 prisoners per 100,000 population. Similarly, a 1% rise in export prices for palm oil increased short-term incarceration by 2% relative to the sample mean.

The effects are reversed in the postcolonial period. Extreme negative or positive rainfall shocks (E), like droughts or floods, increase incarceration rates by 21% and 19%, respectively, relative to a mean of 105 prisoners per 100,000 population.

Figure 4 Effects of rainfall and cash crop price shocks on colonial incarceration rates in Nigeria

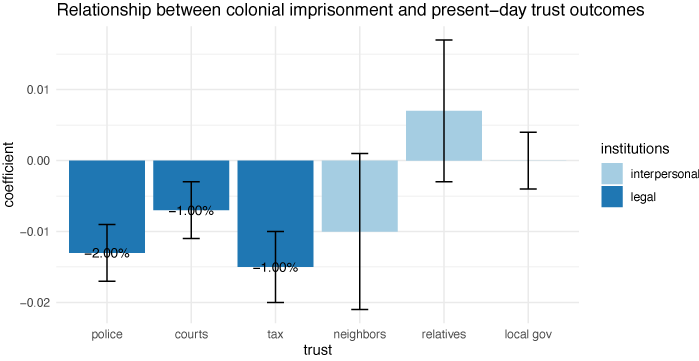

Respondents from areas with higher historic colonial imprisonment report lower trust in legal institutions

Long-term exposure to colonial imprisonment centred on prison labour might have reduced trust in legal institutions, like police. This is particularly the case if communities register these uses of prison labour in local memory as unjust.

We use Afrobarometer data over 2003-2014 from Nigeria on trust in historical legal institutions (e.g. police, courts, tax administration) and trust in individuals or interpersonal trust (e.g. neighbours, relatives, elected local governing council members) to test this hypothesis.

The results, depicted in Figure 5, show that respondents from areas with high levels of colonial imprisonment report significantly lower trust in legal institutions, with no effects on interpersonal trust. We find that the effect is particularly notable for trust in police, where historic colonial imprisonment significantly reduces trust. This is within a context of already low reported trust in police, with most respondents reporting that they trust the police “not at all” or “just a little” (compared to the average response of “somewhat” for trust in relatives).

Figure 5 Relationship between colonial imprisonment and present-day trust in legal institutions and interpersonal trust

Policy implications: Prison labour should be treated with caution

Our results suggest that government proponents of prison labour should act with caution, given its potentially distortionary effects on the incentives for incarceration and long-term deleterious impact on trust in legal institutions.

References

Archibong, B and N Obikili (2020), “Prison labour: The price of prisons and the lasting effects of incarceration”, African Economic History Network, Working Paper No. 52.

BBC (2018), “Tanzania's John Magufuli says prisoners are free labour”.

Branch, D (2005), “Imprisonment and colonialism in Kenya, c. 1930-1952: Escaping the carceral archipelago”, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 38 (2): 239–265.

Campbell, C (2020), “New York’s solution to hand sanitiser shortage: Prison labour, hourly wages below $1”, USA Today.

Doston, J and T Vanfleet (2014), Prison labour exports from China and implications for US policy, US-China Economic and Security Review Commission Staff Research Report.

Jacobson, J, C Heard and H Fair (2017), “Prison: Evidence of its use and over-use from around the world”, Institute for Criminal Policy Research.

World Prison Brief (2020), “World Prison Brief”.