Public service reforms can provoke political backlash from service providers, but when quality increases sufficiently, the electoral rewards can outweigh the costs

Citizens in developing countries routinely demand higher-quality public services, such as education and health. Many of these countries are democracies, where elections are meant to allow voters to hold governments to account. So why hasn’t this resulted in better public services? One hypothesis is that interest groups capture the electoral process and divert state power away from ordinary voters’ preferences (Martinez-Bravo et al. 2017). Another is that voters simply don’t prioritise service quality; there is good evidence that voters punish corruption and other bad behavior, but less research on whether they reward good policies (Ferraz & Finan 2008). Measuring how voters respond to service reforms would illuminate these questions, but it’s tricky – not least because governments tend to be strategic about where they try to make services better. If more people vote for the ruling party where services improve, is that the result of voters rewarding the government, or the government rewarding its supporters?

How did a Liberian school reform affect election outcomes?

To answer this question, I studied the electoral effects of a school policy in Liberia which was allocated randomly (Sandholtz 2023). Before the policy began, 185 eligible public schools were paired up based on their initial similarities. From each pair, one school was chosen at random to receive the policy “treatment.” The remaining schools formed a control group that showed what would have happened in the absence of the policy.

The policy was a public-private school partnership, similar to charter school programmes in the US or academies in the UK. Treated schools came under management by a private school provider and received extra resources. They were prohibited from charging school fees or selecting which students to admit. A previous paper studied the educational effects of the policy: although implementation was uneven, the policy improved various dimensions of school quality on average – including teacher attendance, student attendance, and student test scores (Romero et al. 2020).

To measure the policy’s electoral effects, I looked at how people voted in the presidential election which took place about a year after the policy began. Education policy in Liberia is set by the central government, so attribution for the policy lay with the incumbent executive. I compared votes cast in polling stations near treated schools with those near control schools. (When a polling place was close to multiple schools in the study, I defined its treatment status as the fraction of those schools which were treated.)

Losing votes by improving schools

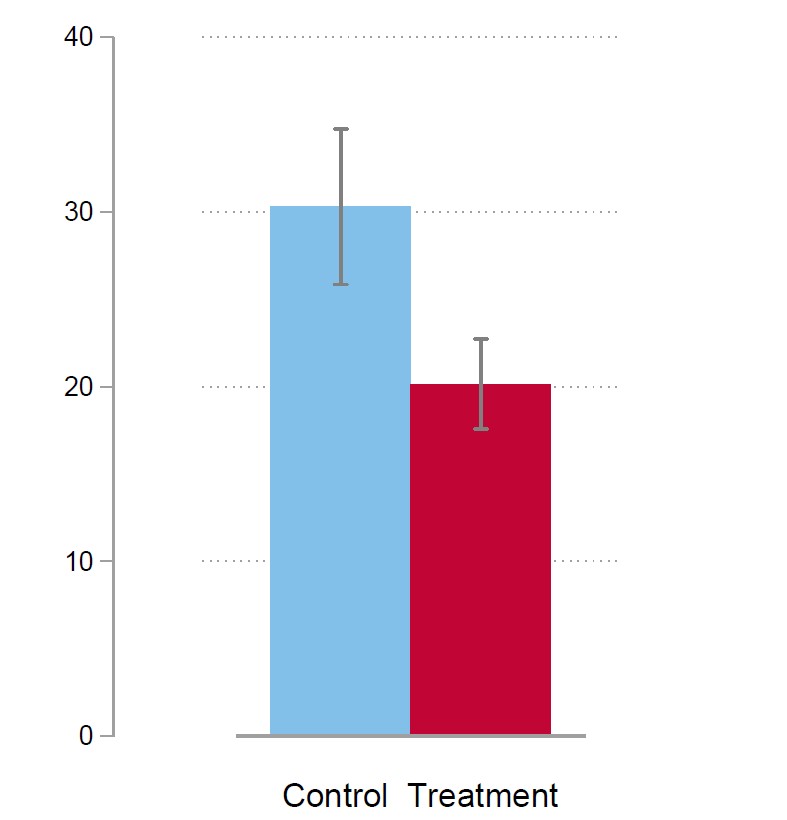

I found that voters near treated schools were significantly less likely to vote for the incumbent party (Figure 1). At polling booths near status-quo schools, the incumbent party’s presidential candidate got about 30% of the vote in the first round. Near treatment schools, this vote share was significantly lower. The same pattern appeared in the runoff. I found no effect on voter turnout, suggesting the effect came through voter persuasion, rather than through the composition of the electorate.

Voters have a lot on their minds; it’s easy to imagine that a school reform could be forgotten in a busy campaign season. But the pattern I uncovered went beyond voter apathy or inattention – the policy caused a meaningful dent in the ruling party’s vote share. Why would improving schools lose votes?

Figure 1: Incumbent party vote share

Notes: This graph shows average vote share for the incumbent party’s presidential candidate in the first round of the 2017 election, separately for the 111 polling places which were within 10km of exactly one control school and the 192 polling places within 10km of exactly one treatment school.

Opposition from public servants can be politically costly

To understand this effect, I needed to survey teachers in treatment and control schools about their political attitudes and election activity. Public school teachers play an important political role in Liberia, as in many parts of the world (Larreguy et al. 2017). Their voices carry weight, as they are often among the most educated and respected members of their community: my survey showed that nearly all have completed secondary school, compared with only 14% of their students’ parents. I found that in the absence of the policy a large fraction of teachers (40%) participated in some kind of election-related activity – operating registration booths or polling booths, encouraging others to vote in general, or campaigning for a particular party.

The school policy dramatically reduced the fraction of teachers involved in political activity, from 40% to 30%. Depending on one’s view of public servants, this may be a good thing – after all, teachers in treatment schools were spending more time at school and more time teaching. But teachers weren’t happy about it. Their job satisfaction fell significantly, and unionised teachers in particular became 16 percentage points less likely to vote for the ruling party.

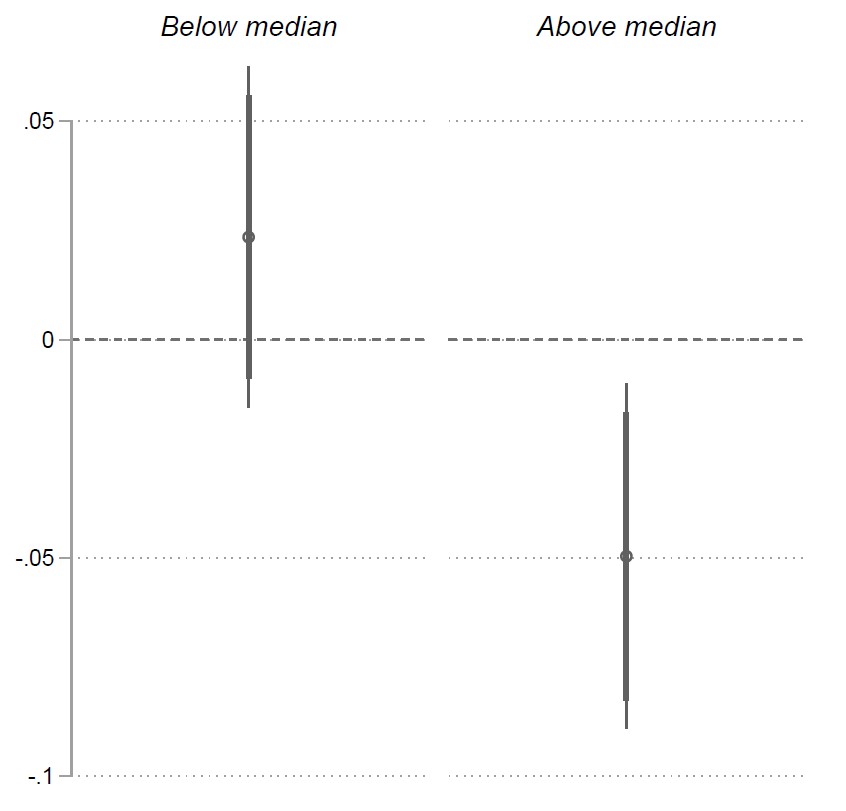

The disengagement of teachers appears to have affected ordinary voters as well. The matched-pair randomisation design of the study allows me to compare how the policy’s effect on voting was different in places where the policy caused big vs. small changes to teachers’ political activity. The negative electoral effects were heavily driven by the places where the policy disengaged teachers most (Figure 2). This suggests that teachers play an important persuasive role with voters and alienating them can be electorally costly.

Figure 2: Effect on incumbent vote share, where teacher disengagement treatment effect was...

Notes: This graph shows the treatment effect of the policy on incumbent vote share, separately for whether the school-pair-level treatment effect on teacher political activity was above vs. below the median. Sample includes all 1200 polling places within 10km of any school in the RCT; treatment defined as the fraction of nearby RCT schools which are treated.

Where services improve sufficiently, the electoral benefits outweigh the costs

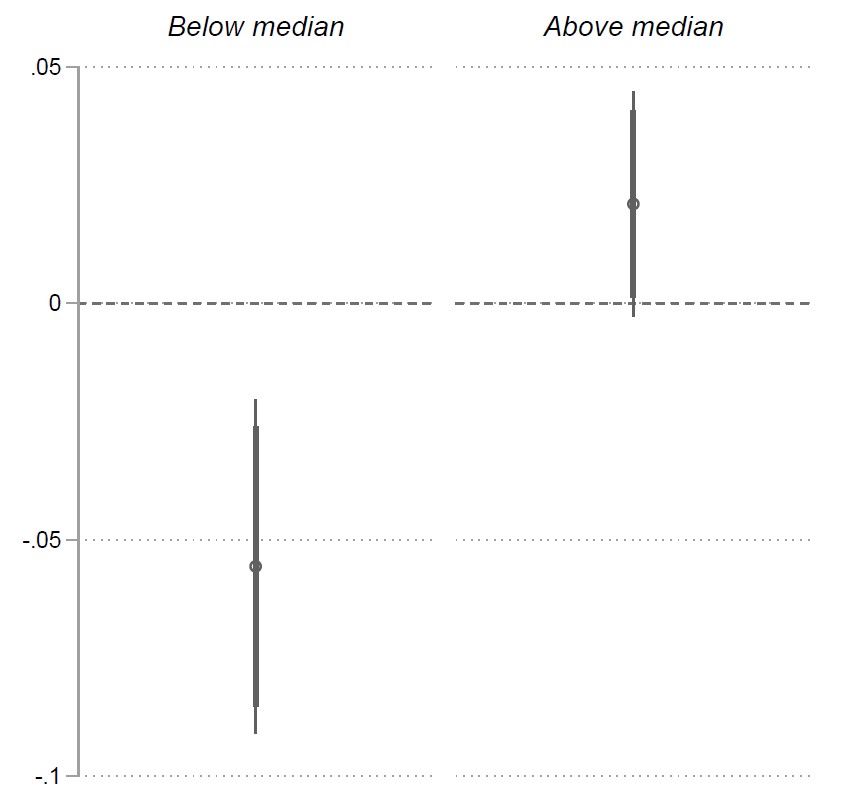

Does this mean that ordinary voters simply don’t value school quality? No. While voters appear to listen to teachers, they also notice school quality improvements for themselves. To demonstrate this, I compare the policy’s electoral effects in places where it caused big vs. small changes to student learning. Negative electoral effects are concentrated in places where the policy didn’t improve test scores by much. By contrast, in places where learning increased a lot, the policy increased votes for the incumbent party (despite teachers’ opposition).

It’s tempting to suspect a direct tradeoff here: help students learn vs. keep teachers happy. In fact, I found very little correlation between the places with the biggest effects on learning and those with the biggest effects on teacher disengagement. Some of the policy’s school operators found ways to increase learning without alienating teachers politically.

Figure 3: Effect on incumbent vote share, where learning treatment effect was...

Notes: This graph shows the treatment effect of the policy on incumbent vote share, separately for whether the school-pair-level treatment effect on student test scores was above vs. below the median. Sample includes all 1200 polling places within 10km of any school in the RCT; treatment defined as the fraction of nearby RCT schools which are treated.

So what?

In Liberia, a policy which improved school quality also alienated teachers, thereby losing votes for the government that implemented it. But voters were sensitive to quality, and where schools improved the most, the electoral benefits outweighed the costs.

Political feasibility often gets overlooked in researchers’ efforts to improve public services. We are constantly adding to the heap of programmes which look effective in a controlled evaluation, but many of these fall apart upon scale-up – and for many more, political constraints preclude any attempt at scale-up to begin with (Bold et al. 2018, Banerjee et al. 2017). Rather than simply grumble about the lack of “political will,” we can strive to build evidence on how elected officials can improve public services while still keeping their jobs.

The good news from this paper is that voters are attuned to service improvements and respond commensurately. This presents an opportunity for researchers and policymakers interested in better services. Policymakers have shown an appetite for rigorous evidence (Hjort et al. 2021), and better communication of the research on (the political feasibility of) service reforms could encourage more politicians to contest elections on these issues.

References

Banerjee, A, R Banerji, J Berry, E Duflo, H Kannan, S Mukerji, M Shotland, and M Walton (2017), “From proof of concept to scalable policies: Challenges and solutions, with an application.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(4): 73–102. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.4.73

Bold, T, M Kimenyi, G Mwabu, A Ng’ang’a, and J Sandefur (2018), “Experimental evidence on scaling up education reforms in Kenya.” Journal of Public Economics, 168: 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.08.007

Ferraz, C and F Finan (2008), “Exposing Corrupt Politicians: The Effects of Brazil’s Publicly Released Audits on Electoral Outcomes *.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2): 703–745. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.2.703

Hjort, J, D Moreira, G Rao and J F Santini (2021), “How research affects policy: Experimental evidence from 2,150 brazilian municipalities.” American Economic Review, 111(5): 1442–1480. https://doi.org/10.1257/AER.20190830

Martinez-Bravo, M, P Mukherjee, and A Stegmann (2017), “The Non-Democratic Roots of Elite Capture: Evidence From Soeharto Mayors in Indonesia.” Econometrica, 85(6): 1991–2010. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA14125

Romero, M, J Sandefur, and W Sandholtz (2020), “Outsourcing Education: Experimental Evidence from Liberia.” American Economic Review, 110(2): 364–400. https://doi.org/10.1257/AER.20181478

Sandholtz, W A (2023), “The Politics of Public Service Reform: Experimental Evidence from Liberia.” CESifo Working Paper Series. Available here.