Policy crackdowns on dowries can reduce their prevalence, but with unintended impacts on women’s decision-making power and domestic violence

Dowries are wealth transfers from the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Despite being illegal, dowry payments in India are widespread and often amount to several times more than a household's annual income (Anderson 2007). Previous studies have linked dowries to gender-based violence, such as sex-selective abortion (Alfano 2017, Bhalotra et al. 2020), bride burning, dowry deaths, and other forms of intimate partner violence (Bloch and Rao 2002, Menon 2020). It has also been shown that higher dowries can increase women's decision-making power in their marital families (Zhang and Chan 1999, Brown 2009, Calvi and Keskar 2020b).

More than one-third of respondents to the 2005-2006 National Family Health Survey report being physically abused by their husbands, and about half are excluded from consequential household decisions. Due to the high social stigma against separation and the low rates of female labour force participation, however, divorce may not be a viable option for many women, even when they are in an abusive marriage (Jacob and Chattopadhyay 2016).

Measuring dowry payments and their impacts on women

In a recent working paper (Calvi and Keskar 2020a), we study the relationship between dowry payments and women's post-marital status through the lens of a non-cooperative bargaining model that links dowries, a wife's bargaining power relative to her husband's, domestic violence, and separation. The model includes some features that are typical in the Indian context, such as the practice of arranged marriage and a strong social stigma against marital dissolution. We obtain several predictions, which we test empirically using amendments to the Indian anti-dowry law as a natural experiment.

We estimate a fall in dowry payments following the amendments, along with a sharp decline in women's decision-making power, a surge in domestic violence, and a decrease in separations. These effects are attenuated when social stigma against separation is low and, in some circumstances, when marital gains are high. To compensate for lower dowries in the marriage market, parents increase their investment in their daughters' human capital.

The Dowry Prohibition Act and its amendments

The Dowry Prohibition Act was introduced in 1961, prohibiting both the giving or receiving of a dowry. The law defined a dowry as "any property or valuable security given or agreed to be given either directly or indirectly (a) by one party to a marriage to the other party to the marriage; or (b) by the parents of either party to a marriage or by any other person, to either party to the marriage or any other person [...]." The Act explicitly excluded from the definition of dowry (and hence from the law itself) any marital transfers "in the case or persons to whom the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) applied." It also stipulated that dowries could be punished either by imprisonment up to six months or with a fine of up to INR 5,000. However, the provisions of the Act were not strong enough, and its attempt to reduce dowries proved mostly unsuccessful (Chiplunkar and Weaver 2019). In response to pressure from advocacy groups (Majumdar 2005), between 1985 and 1986, the Indian government took a series of steps towards tightening the Act.1

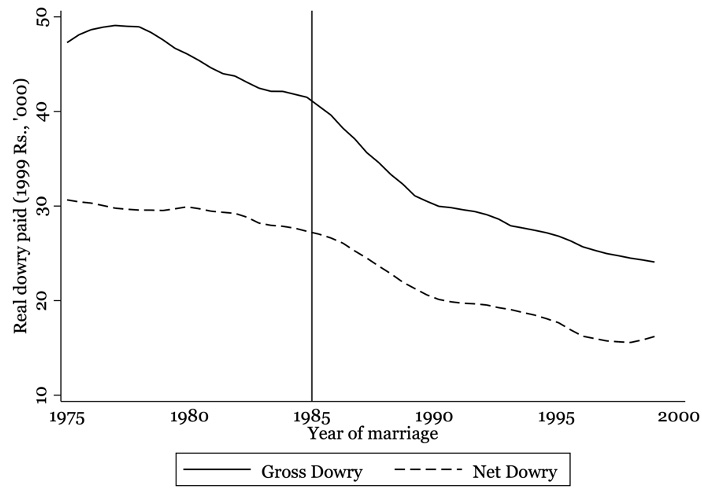

Figure 1 plots real dowry payments (from the 1999 Rural Economic and Demographic Survey, converted in 1999 INR) by year of marriage. Gross dowries are the value of transfers made to the groom's family at the time of marriage, while net dowries are defined as gross dowries minus the value of transfers made from the groom's family to the bride's family. Before 1985, the average gross dowry ranged between INR 42,000 and 56,000 , and net dowries varied between INR 24,000 and 33,000. Between 1986 and 1990, both gross and net dowries declined by more than 20%. Dowry transfers kept falling in subsequent years, but at a slower pace.

Figure 1 Gross and net dowry by year of marriage

Notes: The figure shows local polynomial regressions of real dowry payments on the year of marriage. Gross dowries represent the value of transfers made to the groom’s family at the time of marriage. Net dowries are defined as gross dowries minus the value of transfers made from the groom’s family to the bride’s family. All dowry amounts are from the 1999 REDS and are converted to 1999 Rupees.

In our empirical analysis, we exploit variation in year of the marriage and religion to identify the effect of the amendments on dowry payments and women's status in their marital families using a difference-in-difference framework.2

Key findings

1) The Dowry Prohibition Act amendments were successful at reducing dowries.

We estimate a fall of INR 11,000 in gross dowries and a decrease of INR 6,000 in net dowries following the amendments, which correspond to reductions in dowry payments by 0.2 and 0.1 standard deviations, respectively. Such reductions result from changes occurring both at the extensive and intensive margins. These estimates are not driven by changes in reporting (which would be relevant if survey respondents were less keen to answer dowry-related questions after the reforms) or endogeneity of the time of marriage (which could matter if parents anticipated the introduction of the amendments and scheduled the wedding date of their sons and daughters accordingly). We also analyse the interaction between the Dowry Prohibition Act amendments and other reforms that may have had differential impacts by religion and do not find it critical for our results.

2) The amendments decreased women's decision-making power in their marital families, increased domestic violence, and decreased separations.

In line with our predictions, we find that women's decision-making power declines following the introduction of the 1985–86 amendments and the consequent decline in dowry payments. Specifically, women exposed to the reforms are less likely to participate in decisions about household purchases (by 5.6 percentage points or health and contraception (by 2.9 percentage points). Moreover, the reforms increased the likelihood of severe physical violence (by 3.4 percentage points) and less-severe physical violence (by 2.9 percentage points). Conditional on ever experiencing violence by their husbands, treated women suffer a wider array of injuries.3 Since formal divorce is rare in India, we define women as separated if they report not living together with their husbands. We find that the probability of separation declines substantially after the reforms.

3) The effects of the amendments vary substantially with local social stigma against separation and a couple's gains from marriage.

We uncover substantial heterogeneity in the impact of the 1985–86 reforms on women's status in their marital families. The effects are mitigated in more progressive areas, such as North-East and South India, matrilineal regions, urban areas, and villages with relatively higher rates of separation. We also document differential effects by a couple's gains from marriage, proxied with fertility outcomes (Becker 1973, Angelucci and Bennett 2019). Consistent with the model, we show that the impact of the reforms on women's decision-making power is alleviated when gains from marriage are high, while the impacts on domestic violence and separation are exacerbated.

4) The reforms increased parental investment in the human capital of future brides.

One last prediction of our model is that parental investment in the human capital of future brides should increase following a decrease in dowry. The expectation of a lower dowry payment in the future may incentivise parents to invest in their daughters' human capital to maintain their attractiveness in the marriage market and ensure that they would find a husband (Adams and Andrew 2019). Also, parents may decide to reallocate resources that they would have otherwise saved for their daughters' dowry to alternative expenses that may benefit them (Anukriti et al. 2019).

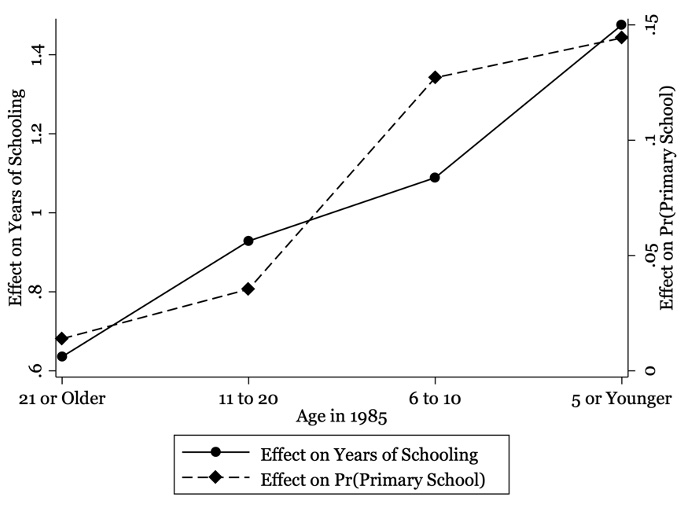

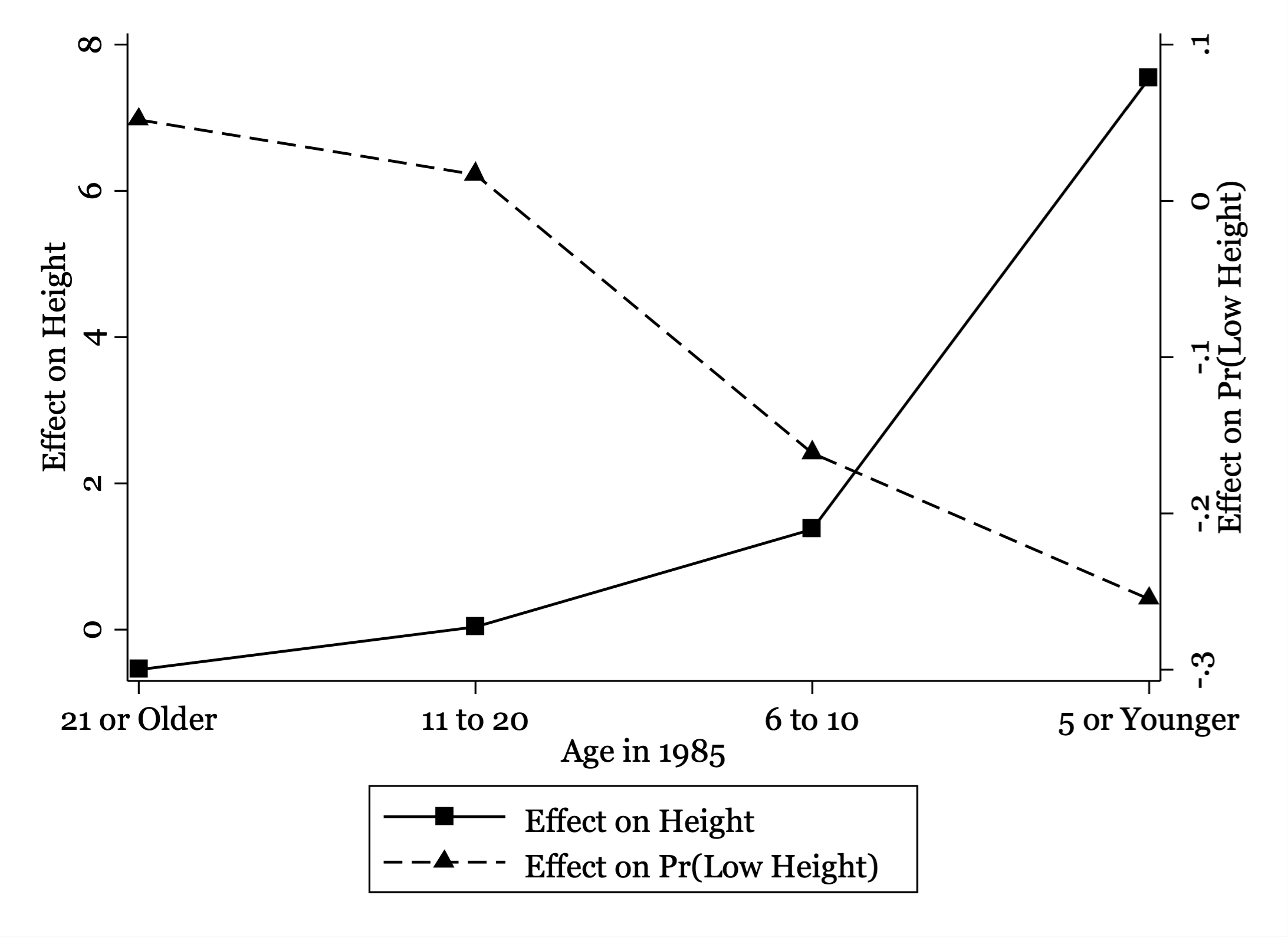

These findings are summarised in Figure 2. Panel A shows the estimated effects of the reforms on women's education outcomes, while Panel B plots the estimated impacts on long-run health. The horizontal axis denotes each cohort's age as of 1985. The estimated coefficients are consistent with our predictions. If possible (that is, for girls who were not too old at the time of the amendments), parents successfully improved their daughters' human capital outcomes; the younger the girls at the time of the reforms, the more pronounced the effects.

Figure 2 Estimated effects on women’s human capital by cohort

Panel A

Panel B

Notes: The figure plots the estimated effects of the 1985-1986 amendments to the Dowry Prohibition Act on years of schooling and the probability of completing primary school (Panel A) and height and the probability of being in the bottom half of the height distribution (Panel B). The effects vary by a woman’s age in 1985.

Takeaways for policymakers

While previous work has stressed the positive impact of anti-dowry policies on son-preference and sex-ratios (Alfano 2017, Bhalotra et al. 2020), we uncover some unintended effects of such policies. We also unveil substantial heterogeneity in the estimated effects, indicating that local social and cultural contexts may matter a great deal when designing anti-dowry policies (Ashraf et al. 2020).

Understanding the link between dowry payments and a woman's well-being at different stages of her life is critical to devise policies that improve the status of Indian women. As one-sixth of the global female population live in India, doing so would represent a significant step toward eliminating gender inequality globally and achieving the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals.

References

Adams, A and A Andrew (2019), “Preferences and beliefs in the marriage market for young brides”, Techical report, IFS Working Papers.

Alfano, M (2017), “Daughters, dowries, deliveries: The effect of marital payments on fertility choices in India”, Journal of Development Economics 125: 89–104.

Anderson, S (2007), “The economics of dowry and brideprice”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 21: 151–174.

Angelucci, M and D Bennett (2019), “The marriage market for lemons: HIV testing and marriage in rural Malawi”, The Review of Economic Studies, Forthcoming.

Anukriti, S, S Kwon and N Prakash (2019), “Saving for dowry: Evidence from rural India”, Unpublished Manuscript.

Ashraf, N, N Bau, N Nunn and A Voena (2020), “Bride price and female education”, Journal of Political Economy 128: 591–641.

Becker, G S (1974), “A theory of marriage: Part I”, Journal of Political Economy 81: 813–846.

Bhalotra, S, A Chakravarty and S Gulesci (2020a), “The price of gold: Dowry and death in India”, Journal of Development Economics 143, 102413.

Bloch, F and V Rao (2002), “Terror as a bargaining instrument: A case study of dowry violence in rural India”, American Economic Review 92: 1029–1043.

Brown, P H (2009), “Dowry and intrahousehold bargaining evidence from China”, Journal of Human Resources 44: 25–46.

Calvi, R and A Keskar (2020a), “`Til dowry do us part: Bargaining and violence in Indian families”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15696.

Calvi, R and A Keskar (2020b), “Dowries, resource allocation, and poverty”, Unpublished Manuscript.

Chiplunkar, G and J Weaver (2019), “Marriage markets and the rise of dowry in India”, Unpublished Manuscript.

Haushofer, J, C Ringdal, J P Sharipo and X Y Wang (2019), “Income changes and intimate partner violence: Evidence from unconditional cash transfers in Kenya”, Techical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Heath, R and X Tan (2019), “Intrahousehold bargaining, female autonomy, and labor supply: Theory and evidence from India”, Journal of the European Economic Association.

Jacob, S and S Chattopadhyay (2016), “Marriage dissolution in India”, Economic & Political Weekly 51, 25.

Majumdar, M (2005), Encyclopaedia of gender equality through women empowerment, Sarup & Sons.

Menon, S (2020), “The effect of marital endowments on domestic violence in India”, Journal of Development Economics 143, 102389.

Zhang, J and W Chan (1999), “Dowry and wife’s welfare: A theoretical and empirical analysis”, Journal of Political Economy 107: 786–808.

Endnotes

1 The 1985 Dowry Prohibition Rules established that a list of wedding gifts must be maintained. The list must include a brief description of each gift, the approximate value of the gift, the name of the person who has given the gift and his/her relationship with the bride and the groom. Another amendment followed in 1986, which raised the minimum punishment for taking or abetting dowry to five years of imprisonment and to a fine of not less than 15,000 Rupees (or the amount of the value of the dowry, whichever is higher). The 1986 amendment also shifted the burden of proving that no funds were exchanged to the person who receives the dowry. Finally, the amendment gave power to any state government to appoint "as many Dowry Prohibition Officers as it thinks fit," to prevent the taking or demanding of dowry and to collect the necessary evidence for the prosecution of violators of the Dowry Prohibition Act.

2 Our identification strategy relies on the parallel trend assumption, which requires that, in the absence of the 1985-1986 amendments, the evolution of dowry payments, domestic violence, women's decision power and human capital, and separations should have been the same for Muslims and non-Muslims. We use several approaches to confirm that validity of our empirical strategy.

3 To gauge the magnitudes of the estimated effects, we compare them to alternative policies. For example, Heath and Tan (2019) estimate that amendments to Hindu Succession Act (that equalised inheritance rights for women and men in several Indian states between 1976 and 2005) increased women's participation in decisions about large purchases by 10 pp and about their own health by 5 pp. In the Kenyan context, Haushofer et al. (2019) find that a cash-transfer targeting men (approximately equal to $700 PPP, on average) decreased the likelihood of women being slapped by the husband by 10 pp (32%) and kicked, dragged, or beaten by 9 pp (59%). In our context, the Dowry Prohibition Act amendments (which reduced gross dowries by roughly $1,200 PPP and net dowries by $600 PPP on average) increased the likelihood of severe and less-severe physical violence by 33% and 9%, and the likelihood of ever suffering any injury by the husband by 16%.