Congestion in Indian courts of justice distorts firms’ organisation and sourcing decisions and lowers aggregate productivity

During the last two decades, economists have pointed out that in developing countries firms seem to use inefficient quantities of factor inputs like capital and labour in their production process. These distortions are so large that their removal would likely lead to large increases in industrial productivity and the level of development of these countries (Restuccia and Rogerson 2008, Hsieh and Klenow 2009). Where do these distortions come from? And how do these distortions affect individual production decisions and aggregate productivity?

The enforcement of contracts in India

In Boehm and Oberfield (2018) we study the use of intermediate inputs (materials) by manufacturing plants in India and link the patterns we find to a major institutional failure: the long delays that petitioners face when trying to enforce contracts in a court of justice. India has long struggled with the sluggishness of its judicial system. Since the 1950’s, the Law Commission of India has repeatedly highlighted the enormous backlogs and suggested policies to alleviate the problem, but with little success. Some of these delays make international headlines, such as in 2010, when eight executives were convicted in the first instance for culpability in the 1984 Bhopal gas leak disaster. One of them had already passed away, and the other seven appealed the conviction (Financial Times 2010)

These delays are not only a social problem, but also an economic problem. When enforcement is weak, firms may choose to purchase from suppliers that they trust (relatives, or long-standing business partners), or avoid purchasing the inputs altogether such as by vertically integrating and making the components themselves, or by switching to a different production process. These decisions can be costly. Components that are tailored specifically to the buyer (‘relationship-specific’ intermediate inputs) are more prone to hold-up problems, and are therefore more dependent on formal court enforcement.

Intermediate input mixes of manufacturing plants

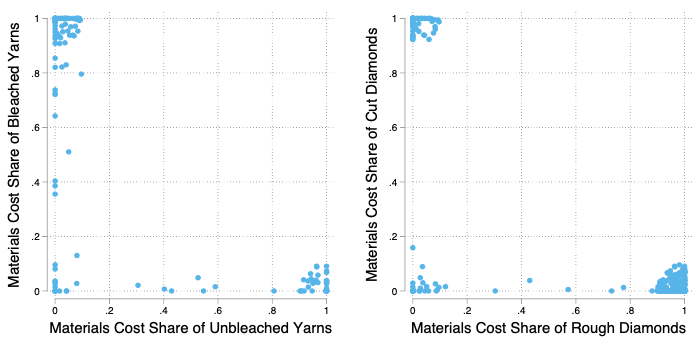

Our production data comes from the 2000/01 to 2012/13 rounds of the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI), which is India’s main source of official statistics on the formal manufacturing sector. The ASI covers all plants that have more than 20 employees (or 10 employees if the plant uses power). An interesting feature of the dataset is that it contains detailed product-level information on each plant's intermediate inputs and outputs. These data on inputs allow us to better differentiate between different organisational modes of production. As an example, Figure 1 shows different input mixes among plants that produce bleached cotton cloth and for polished diamonds. These different input mixes correspond to different degrees of vertical integration of the plants: plants that produce polished diamonds from raw diamonds do both cutting and polishing, whereas plants that produce polished diamonds from cut diamonds do just the polishing. Presumably, much of this heterogeneity in organisation or technology will arise naturally and is not associated with inefficiencies. Nevertheless, we will show that some of it is driven by weak contract enforcement.

Figure 1 Heterogeneity in input mixes within narrow industries

Notes: Each dot refers to a plant-year observation, single-product plants only. Points have been jittered to improve readability.

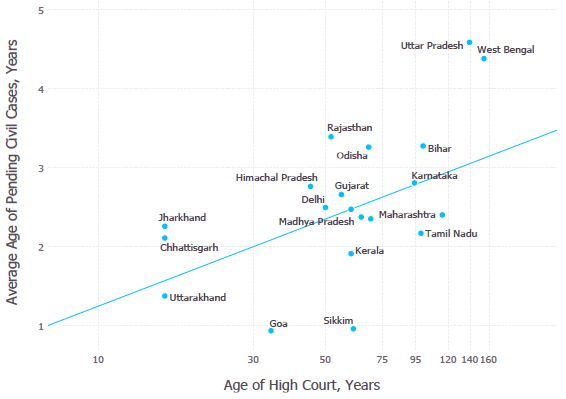

We relate the plants’ expenditures on different types of inputs to the court delays in its state. We measure court delays as the average age of pending High Court cases, which we construct from microdata assembled by the Indian NGO Daksh (Narasappa and Vidyasagar 2016). Delays vary starkly across states: the mean case is one year old in the fastest state, and four and a half years in the slowest state. We also employ an instrumental variable strategy, where we use the facts that:

- backlogs accumulate over time, hence the oldest high courts are the most congested ones (see Figure 2); and

- new courts have been created mostly through the split of states, which has happened for reasons unrelated to court quality or the structure of industry.

We therefore instrument the average age of pending cases by the age of the high court.

Figure 2 Age of the High Court and speed of enforcement

A systematic distortion

We find that the use of materials in production appears systematically distorted in states where courts are slow:

- In industries that tend to rely on relationship-specific inputs, manufacturing plants have lower shares of materials expenditure in total cost in states with more congested courts.

- Within narrowly defined industries (5-digit), plants in states with more congested courts tilt their input mix towards the use of homogeneous (non-relationship-specific) intermediate inputs.

- Finally, plants in industries that tend to rely heavily on relationship-specific inputs are more vertically integrated when located in states with more congested courts. We measure the degree of vertical integration of plants by looking at the ‘upstreamness’ of the input mix from the plant’s output. For example, we classify a shirt manufacturer that uses yarn as an intermediate input (and hence does both weaving and tailoring herself) as more vertically integrated than a shirt manufacturer that uses only cloth (and therefore does just the tailoring).

Quantifying the role of contracting frictions

To quantify the impact of court delays on aggregate productivity, we construct and estimate a general equilibrium model. In the model, producers in each industry may choose from a range of different production functions which correspond to different technologies or organisational modes of production. Producers draw potential suppliers of each intermediate input they might use. To use each supplier, the buyer faces a match-specific productivity. Some inputs require customisation, and using the input gives rise to a holdup problem. Good contract enforcement, either formal or informal, can alleviate the problem. We model the severity of the holdup problem as random and match-specific. This captures the idea that for some suppliers (i.e. a close relative, those with whom there are repeated interactions) there are ways to resolve contracting problems informally, whereas for others the problem will be more severe. Each producer thus faces the choice of what production function to use and from which suppliers to source inputs.

Poor contract enforcement distorts production in two ways:

- Direct impact: If a producer uses a supplier for which there is a severe contracting friction, use of that input will be distorted, which will directly lower productivity.

- Indirect impact: A severe contracting problem might lead a producer to switch to a more costly supplier or less efficient technology to avoid the friction. While this is costly, a methodology that measured distortions using cost shares (e.g. Hsieh and Klenow 2009) would detect only the direct impact of the distortion, not the indirect impact.

An important property of the model is that even in the absence of distortions, the equilibrium would exhibit plants that produce in a variety of ways with different bundles of inputs and different cost shares. We identify wedges from systematic differences in first moments, which helps to alleviate concerns about mismeasurement being interpreted as misallocation. At the same time, the structure of the model allows us to account for both the direct and indirect impact when estimating the magnitude of the contracting frictions.

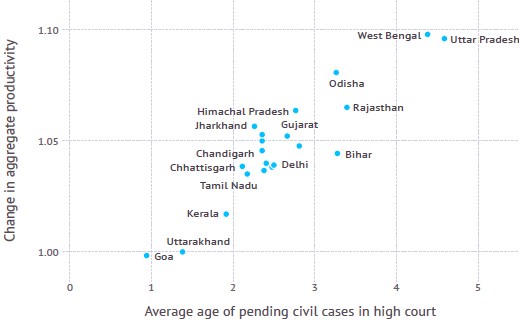

Results: Improving contract enforcement

Our results suggest that courts may be important in shaping aggregate productivity. For each state we ask how much aggregate productivity of the manufacturing sector would rise if court congestion were reduced to be in line with the least congested state. On average across states, the boost to productivity is roughly 5%, and the gains for the states with the most congested courts are roughly 10% (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Counterfactual increases in aggregate productivity

Notes: The figure shows the counterfactual increases in aggregate manufacturing sector productivity if the average age of pending cases were set to one year (1.00 = no change)

Policy recommendations: Improving courts of justice important

These estimates suggest that the economic benefits to improving courts of justice may be large. While we do not have direct estimates of how costly it would be to improve court efficiency, one should note that India spends only 0.12% of GDP on its judiciary (Government of India 2015a,b) – a small amount compared to the potential benefits from improving courts. Furthermore, while we measure one channel, there are many other ways that improved contract enforcement could increase productivity and welfare, for example by improving access to capital and labour.

Editors' note: This column is based on a PEDL study.

References

Boehm, J and E Oberfield (2018), “Misallocation in the market for inputs: Enforcement and the organisation of production”, NBER Working Paper 24937.

Financial Times (2010), “Painfully slow justice over Bhopal”, 7 June.

Government of India (2015a), “Agenda for the ninth meeting of the Advisory Council of the National Mission for Justice Delivery and Legal Reforms“, Department of Justice.

Government of India (2015b), “Union Budget 2014/15”, Ministry of Finance.

Narasappa, H and S Vidyasagar (2016), State of the Indian Judiciary: A Report by Daksh, Eastern Book Company.

Hsieh, C and P Klenow (2009), “Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(4): 1403-1448.

Restuccia, D and R Rogerson (2008), “Policy distortions and aggregate productivity with heterogeneous establishments”, Review of Economic Dynamics 11(4): 707-720.