Nearly 160 years after the end of slavery, significant disparities persist between Black and white Americans. Those whose ancestors were enslaved until the Civil War have less education, income, and wealth than Black families whose ancestors were free – disparities that persist not simply because of slavery, but because most families enslaved until the Civil War lived in states with strict Jim Crow regimes when slavery ended.

Editor's note: This article originally appeared on VoxEU.

Nearly 160 years since the end of slavery, significant disparities in education, income, wealth, and other metrics continue to exist between Black and white Americans (e.g. Margo 2016, Chetty et al. 2018, Derenoncourt et al. 2022). Policy proposals designed to compensate descendants of enslaved people have recently regained both public and academic attention (Coates 2014, Darity and Mullen 2020a, 2020b, Ray and Perry 2020). Still, the concept of reparations remains divisive, possibly because perceptions diverge on why these inequalities persist. Black Americans and white Democrats tend to attribute racial inequality to past injustices, whereas white Republicans often point to individual choices or insufficient effort (Alesina et al. 2021).

Our latest research presents unprecedented evidence of how deeply racial inequality was entrenched by anti-Black institutions (Althoff and Reichardt 2024). Our results reveal that Black Americans whose ancestors were enslaved until the Civil War still have far lower economic status than Black Americans whose ancestors were free earlier. When and where their environment allowed, formerly enslaved families made considerable economic strides in the decades after becoming free. However, most families who were enslaved until the Civil War lived in regions where Jim Crow laws significantly impeded their economic advancement for almost a century after emancipation. Our evidence highlights the persistent systemic oppression of Black families in the Jim Crow South, which has severely limited their ability to achieve their full economic potential.

It is only recently that such research has become possible. Measuring the degree to which Black families’ economic status is still influenced by the experiences of their ancestors is challenging. Many Black Americans themselves may not know their ancestors’ full stories, making it difficult to measure the long-term effects of enslavement and discrimination. Therefore, researchers face the difficult task of gathering and tracking vast amounts of modern and historical data for individual families to quantify the effects of these experiences. However, recent methodological breakthroughs, such as automated record linkage (Abramitzky et al. 2021), have made this task feasible.

We have developed two innovative methods to identify the enslavement status of Black Americans’ ancestors. The first approach involves tracing the records of Black Americans from the present day back 160 years to their ancestors’ records. The earliest US censuses, in 1850 and 1860, recorded free Black Americans but not enslaved individuals; we classified those whose ancestors can be found in these censuses as descendants of free Black Americans and those whose ancestors could not be found as descendants of enslaved Black Americans. The second method is based on the surnames of Black families. We leveraged the fact that the surnames of free Black Americans often differ from those chosen by enslaved individuals who were freed after the Civil War. Specifically, we assessed the probability of each surname being linked to free Black families versus enslaved families by examining changes in surname frequency across censuses, comparing records exclusively listing free Black Americans to those incorporating (formerly) enslaved families.

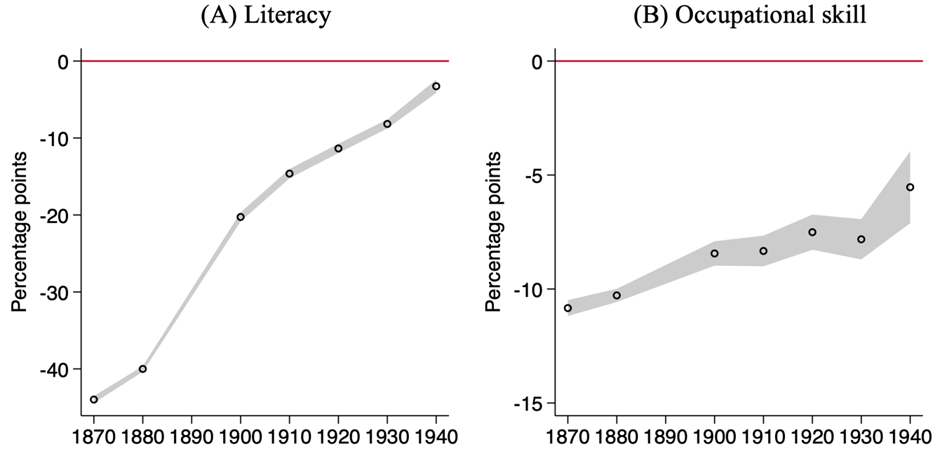

Our new methods revealed a stark disparity: Black Americans whose ancestors were enslaved until the Civil War still face significant educational, income, and wealth gaps compared to descendants of those who gained their freedom earlier (see Figure 1). This gap, which we refer to as the ‘Free-Enslaved gap’, remains massive even in 2023, taking on magnitudes equal to 20–60% of the corresponding Black-white gaps.

Figure 1: Free-enslaved gap, 1870–1940

Notes: Figure shows the gaps in literacy and occupation skill among prime-age (20–54) male descendants of enslaved versus free Black Americans in each census decade.

Barriers to Black economic progress after slavery

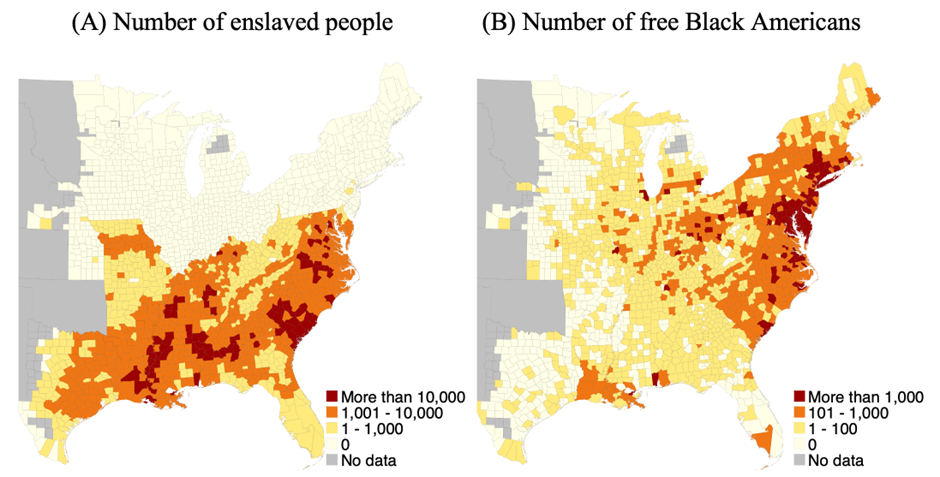

In 1865, when the Civil War ended slavery in the US, two groups of Black Americans existed. One group comprised newly freed Black families in the South (see Figure 2), who often emerged from the Civil War with no belongings and no ability to read or write. The other group was smaller and consisted of Black Americans who had been free before the war, many of them for several decades. These families could be found in both the North and South and had gained some level of wealth and education.

Figure 2: Population by county in 1860

Notes: Figure shows the population sizes of enslaved Black Americans and free Black Americans in the 1860 census.

After the abolition of slavery, Black Americans experienced a short period of progress known as Reconstruction. During this time, many Black Americans learned to read and write. Black men’s participation in voting also reached levels comparable to today’s rates, and many held political office. These achievements were possible due primarily to the presence of Northern Union troops, which ensured that the basic rights of Black Americans were protected in the South after the Civil War.

However, the Jim Crow era began to significantly limit Black economic progress when Reconstruction efforts were abandoned, only 12 years after the end of slavery. Immediately after a political compromise led to the withdrawal of Northern troops in 1877, Southern states began to pass restrictive laws designed to limit Black economic progress. The Jim Crow regimes in different states had varying intensities, often taking away Black Americans’ ability to vote, restricting their economic and geographic mobility, and racially segregating various aspects of life. Black economic progress began to drastically diverge across Southern states after Jim Crow regimes were implemented.

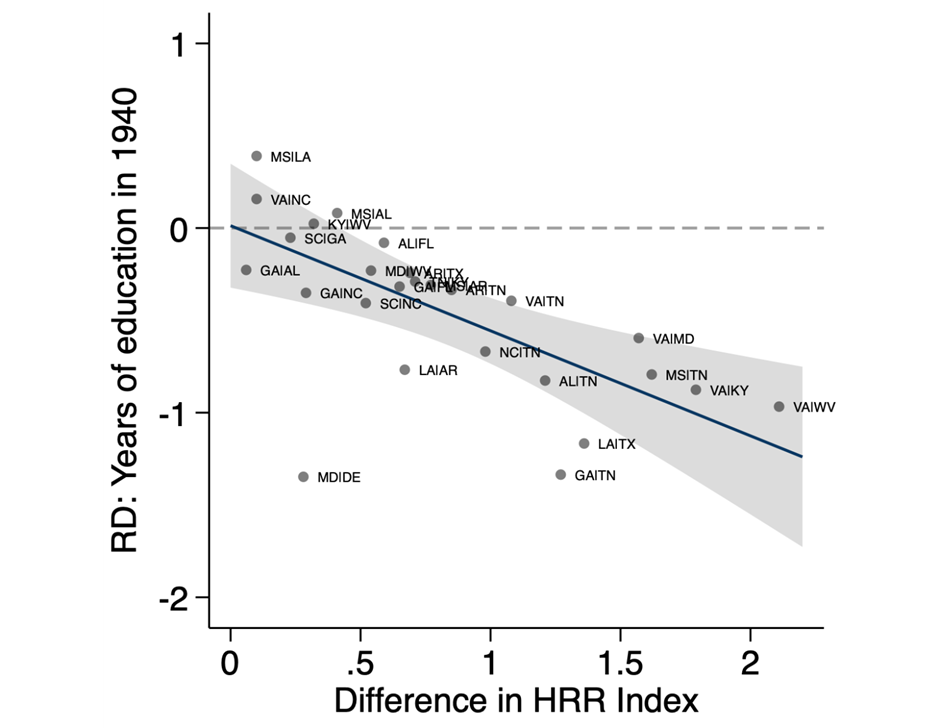

Our results show that Black families whose ancestors had been freed in states that adopted more oppressive policies made far less economic progress during the next century than those freed just a few miles away, on the less oppressive side of the same border (see Figure 3). To investigate the impact of Jim Crow, we zeroed in on Black families whose ancestors were freed in counties located along state borders within the South. For example, under Louisiana’s strict Jim Crow regime, Black families attained over a year’s less education by 1940 compared to families who were freed just a few miles away, in Texas – a state with a far weaker Jim Crow regime. The differences in long-term economic progress that emerged across each state border within the South can be explained by the differential intensity of their Jim Crow regimes. Jim Crow negatively impacted not just education, but also voter participation, school quality, and many other outcomes that were critical to Black economic progress.

Figure 3: Regression discontinuity estimates and Jim Crow

Notes: Figure relates regression discontinuities (RD) in Black economic progress across state borders (vertical axis) to differences in the intensity of states’ Jim Crow regimes (horizontal axis). Each separate RD estimate is measured in 1940 years of education for Black families whose ancestors were freed on different sides of state borders in 1865. Each label shows the more oppressive before the less oppressive state as measured by the Historical Racial Regime index (Baker 2022). Negative estimates reflect lower education in more oppressive states. Lines show the best linear fit between RD estimates and the differences in Jim Crow intensity, weighted by the inverse of the estimates’ standard error. Shaded areas represent robust 95% confidence bands.

Our findings not only demonstrate the severe, negative impact of Jim Crow laws on the economic progress of the Black community, but also suggest that Jim Crow is the main reason why descendants of families enslaved until the Civil War still have lower economic status than Black families who were freed earlier. If formerly enslaved families had not been concentrated in the centre of Jim Crow, but rather distributed across the country like free Black Americans, the gap between free and enslaved Black families would have been closed by 1940.

Repairing the impact of historical discrimination

While our work stresses that systemic barriers have been a key reason why past discrimination continues to shape racial disparity today, we also show that targeted policies can repair the harm done by those institutions. Specifically, we study one of the most successful educational interventions in US history: the Rosenwald School programme (1910s to 1930s). This programme brought 5,000 schools for Black children to the South, schooling one-third of all Black children during the late Jim Crow era (Aaronson and Mazumder 2011). We show that Black children under the most oppressive regimes benefited the most from gaining access to such a school. This result highlights the immense demand for education that existed among Black Americans even if the returns to education were likely limited at the time.

The economic fate of Black families today remains heavily influenced by conditions set in place more than 160 years ago, underscoring the urgent need for policies that address these deep-rooted disparities. Our research highlights the ways that institutions like Jim Crow, established post-slavery, significantly hindered the economic advancement of formerly enslaved people and their descendants (see also Katznelson 2006, Acharya et al. 2018). Consequently, reparations should not only acknowledge the legacy of slavery but also address subsequent anti-Black institutions. For example, US Senator Raphael Warnock proposed legislation in 2023 to repair the negative effects of discriminatory practices that largely excluded Southern Black veterans from one of the most significant government initiatives in US history, the WWII GI Bill (Warnock 2023, Bound and Turner 2003, Fetter 2013, Althoff and Szerman 2024).

References

Aaronson, D and B Mazumder (2011), “The Impact of Rosenwald Schools on Black Achievement”, Journal of Political Economy 119(5): 821–88.

Abramitzky, R, L Boustan, K Eriksson, J Feigenbaum and S Pérez (2021), “Automated Linking of Historical Data”, Journal of Economic Literature 59(3): 865–918.

Acharya, A, M Blackwell and M Sen (2018), Deep Roots: How Slavery Still Shapes Southern Politics, Princeton University Press.

Alesina, A, M Ferroni, G Giupponi, C Landais, A Lapeyre and S Stancheva (2021), “Perceptions of racial gaps, their causes, and ways to reduce them”, VoxEU.org, 12 November.

Althoff, L and H Reichardt (2024), “Jim Crow and Black Economic Progress After Slavery”, Working Paper.

Althoff, L and C Szerman (2024), "The G.I. Bill and Black-White Wealth Disparities", Work in Progress.

Baker, R (2022), “The Historical Racial Regime and Racial Inequality in Poverty in the American South”, American Journal of Sociology 127(6): 1721–969.

Bound, J and S Turner (2003), “Closing the Gap or Widening the Divide: The Effects of the G.I. Bill and World War II on the Educational Outcomes of Black Americans”, Journal of Economic History 63(1): 145–77.

Chetty, R, M Jones, N Hendren and S Porter (2018), “Race and economic opportunity in the United States”, VoxEU.org, 27 June.

Coates, T (2014), “The Case for Reparations”, The Atlantic, June.

Darity, W and K Mullen (2020a), From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century, University of North Carolina Press.

Darity, W and K Mullen (2020b), “Black reparations and the racial wealth gap”, Brookings, 15 June.

Derenoncourt, E, C H Kim, M Kuhn and M Schularick (2022), “Wealth of two nations: The US racial wealth gap, 1860–2020”, VoxEU.org, 4 July.

Fetter, D (2013), “How Do Mortgage Subsidies Affect Home Ownership? Evidence from the Mid-Century GI Bills”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 5(2): 111–47.

Katznelson, I (2006), When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America, New York: W. W. Norton.

Margo, R (2016), “The persistence of racial inequality in the US”, VoxEU.org, 8 June.

Perry, A and R Ray (2020), “Why we need reparations for Black Americans”, Brookings, 15 April.

Warnock, R (2023), “Senator Reverend Warnock Reintroduces Legislation to Provide Full GI Bill Benefits to Families of Previously-Denied Black WWII Veterans”, warnock.senate.gov, 8 November.