Providing poor Indian women with more control of their potential wages increased labour force participation and led to more progressive gender norms

India’s rate of female labour force participation not only ranks among the world’s lowest, but is also on a downward trend. Despite rapid economic growth, reduced fertility, and greater female educational attainment, the rate dropped from 37% in 1990 to 28% in 2015. Yet nearly one-third of Indian housewives express an interest in working (Fletcher et al. 2017). In the coming years, India’s growth trajectory and the wellbeing of its population will depend on how effectively it uses public policy to help these women access labour markets. Giving women more direct control of their potential wages may be one way to do that.

We conducted a large-scale experiment in partnership with government and bank authorities in rural areas of Madhya Pradesh state. As a baseline, all women received new low-cost bank accounts that could be accessed at a local banking kiosk. From that point, we find that giving women basic account training, alongside signing them up for direct-deposit of government ‘workfare’ wages, led to them working more outside their homes, liberalised social norms, and increased empowerment among those with the least labour-market experience (Field et al. 2019).

The labour supply puzzle

The idea that increasing women’s financial control also increases their labour supply does not fit neatly into traditional economic models. A neoclassical view of household decision-making, which sees the family as a single unit, predicts that a woman’s labour supply should be unaffected by direct deposit and training, since these interventions have no impact on market wages or account ownership.

Other theories view households as a collection of individuals where men and women bargain over decisions. These predict that greater bargaining power for women (which is what, we argue, financial control gives them) leads to them cutting back on work and enjoying more leisure. This ‘income effect’ is used to explain reduced female labour force participation in a number of contexts. For example, Angrist (2002) uses it to explain why a lower female-to-male sex ratio among immigrants in the US was associated with lower female labour force participation. In this view, the women were more in demand as wives and therefore could bargain for higher-earning husbands and more leisure time. Rangel (2006) uses it to explain why alimony laws more beneficial to women in Brazil led to lower female labour force participation, and Chiappori et al. (2002) find that divorce laws that are favourable to women reduce married women’s labour supply.

So why, in our context, would greater female bargaining power increase women’s labour supply? We argue that one missing element is norms: if husbands face a higher reputational cost than wives when women work, women might stay out of the labour force to appease their husbands. When female bargaining power increases, some wives may assert their own preferences and start working. This interpretation is bolstered by our finding that the effects were strongest in households where women had the least prior labour market experience and husbands internalised stronger norms against female work.

The intervention: A woman’s own account, plus direct deposit and training

We conducted our study in northern Madhya Pradesh, an area with low female labour force participation and restrictive gender norms. 70% of control group women stated their husband was the primary person who decided whether she worked outside the home, and just half of respondents had gone to the local market alone in the past year. For women, the government’s workfare programme, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), presents an important opportunity to undertake wage labour close to their homes.

In 2012, the Indian government mandated that wages from MGNREGS be paid digitally into individually-controlled accounts. While a series of government programmes theoretically enabled women to have MGNREGS wages directly deposited into their own accounts, officials were slow to target women. Rather, a woman’s wages still went into a household account, typically controlled by her husband.

We collaborated with the state government and two large banks on a randomised controlled trial in 197 village clusters, known as gram panchayats (GPs). In a random subset of GPs in our study area, we made a push to open individual accounts for women at the GP’s community banking kiosk. In half of these GPs, we enabled direct deposit of women’s MGNREGS wages in these accounts. Finally, we randomised a short training programme that gave women basic instructions for how to use their new account at the kiosk. In our analysis, we focus on measuring the effect of offering newly banked women direct deposit and training, relative to just opening accounts.

In looking at our results, it is helpful to keep two distinctions in mind. First, the direct-deposit and training interventions did not entail providing women with financial inclusion, but financial control. This is because all the women in our comparison group were offered new accounts, with very similar account opening rates across treatment arms. Second, the effects were different for women who had worked in MGNREGS at baseline and those who had not – though someone in their household must have worked in the programme in order for them to be included in the study. We refer to women who had not worked in MGNREGS at baseline as socially constrained to reflect that, absent intervention, they are less likely to work, less empowered, and their husbands are more likely to subscribe to norms against female work.

Higher labour force participation, more financial autonomy and more progressive gender norms

We find that after one year, women who received digital wage deposits and training were working more, both in workfare and in private-sector employment. This increase occurred despite no change in market wages.

Direct deposit and training also led to sizeable gains in female financial autonomy. Three years after the intervention, we observe more account use and more banking autonomy (a 0.19 standard deviation unit increase), as measured by whether a woman goes to the bank on her own and is comfortable transacting independently. These gains are particularly notable given the limits on women’s mobility and agency in our setting.

Looking more long-term, we see that direct deposit and training had impacts on gender norms related to female work. Three years after the intervention, we measured norms and beliefs governing female work. Relative to women who received only bank accounts, women who received direct deposit and training were more likely to hold female work in high regard, were less judgmental of other households where women worked, and reported that working women bear fewer social costs. Their husbands did not change their personal beliefs, but became less likely to report that husbands suffer social costs when their wives work.

Effects on socially constrained women

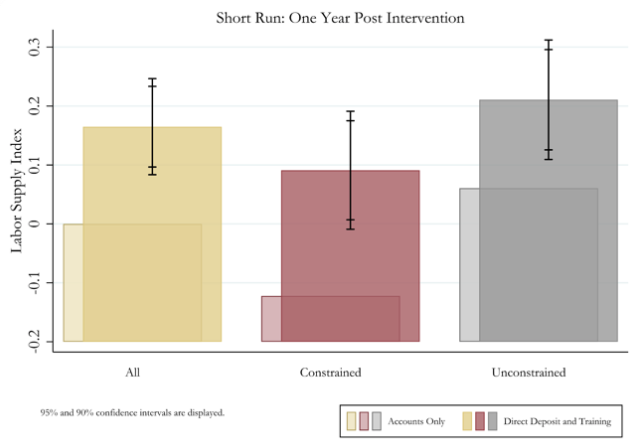

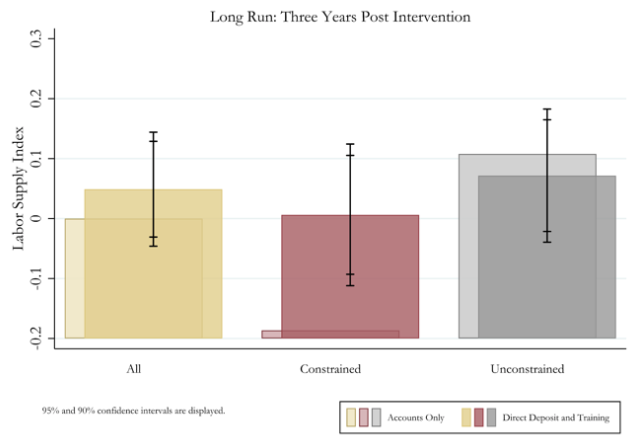

If we narrow our focus to the women who had not worked for MGNREGS before, the effects of increased financial control are particularly strong. First, the increases in labour supply persisted. As figure 1 below shows, socially constrained women offered direct deposit and training continued to work more over three years after the initial intervention. This is especially striking since the government had started its own push to sign women up for direct deposit between our short- and long-run surveys.

On top of this, socially constrained women also became more empowered. Direct deposit and training increased the average value of the empowerment index, which measures economic activity, mobility, and decision-making power, both in the short- and long-run. This closed the empowerment gap between these women and others in the sample.

Figure 1 Short- and long-run impacts on labour supply

Policy implications: A new way to change norms?

Strikingly, the present study made no direct attempt to change norms, beliefs, or attitudes towards women’s work. Providing more direct financial control to women seems to have accomplished this on its own. This is an important insight for policymakers, since campaigns focused on directly changing norms can be expensive and difficult to scale.

More broadly, our results highlight how gender targeting and woman-centred design of social programmes can have effects that reverberate far outside the programme itself. Such intentional policy design can reshape how women interact with their households, local economies, and even affect broader views on gender.

Author’s note: We thank Vestal McIntyre for extensive editorial assistance.

References

Angrist, J (2002), “How do sex ratios affect marriage and labour markets? Evidence from America’s second generation”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(3): 997–1038.

Chiappori, PA, B Fortin and G Lacroix (2002), “Marriage market, divorce legislation, and household labour supply”, Journal of Political Economy 110(1): 37–72.

Field, E, R Pande, N Rigol, S Schaner and C Troyer Moore (2019), “On her own account: How strengthening women's financial control affects labour supply and gender norms”, NBER Working Paper 26294.

Fletcher, E, R Pande, and C Troyer Moore (2017), “Women and work in India: Diagnostics and a review of potential policies”, Working Paper.

Stevenson, B (2008), “Divorce law and women's labour supply”, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 5(4): 853–873.