Sharply increasing inequality became an integral part of the narrative on Chinese development since the beginning of the reform process in 1978. Over the past decade, however, many studies have argued that inequality has been plateauing, or even declining. This column uses several datasets, including household surveys and regional-level government statistics, to show evidence of a mitigation of inequality in the early 21st century, and indeed, declining rates over recent years. Possible drivers of this turnaround are urbanisation, transfer and regulation regimes, and tightening rural labour markets.

Alongside the spectacular growth and extraordinary reductions in poverty – perhaps the most dramatic in human history – the evolution of Chinese income inequality since the start of the reform process in 1978 has been a focus of interest among analysts and policymakers. Sharply increasing inequality became an integral part of the narrative on Chinese development, with some commentators arguing that this was the inevitable price to be paid for the high rates of growth, while others warned of the social consequences of these growing gaps.

However, as more data have accumulated, attention has shifted to the evolution of inequality in China in the 2000s, including the present decade – the years after 2010. From the mid-2000s onwards, a number of studies began to argue that the rise in inequality was being mitigated, and that inequality could be plateauing or even going down (an early example is Khan and Riskin 2005).

Our recent research attempts to provide a comprehensive assessment of what the data show, a deeper look into the patterns of inequality change, and preliminary explanations for the trends observed (Kanbur et al. 2017). Our basic conclusion is that there does indeed appear to be a turnaround taking place in Chinese inequality from the latter part of the first decade of the 2000s, and that the explanations lie in policy changes and in the nature of structural transformation in China.

Our assessment uses household-level survey data from the Chinese Household Income Project (CHIP) for 1995, 2002, and 2007, and from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) for 2010, 2012, and 2014.1 A number of issues of completeness and comparability have to be addressed in order to use these data, but between them they provide a 20-year perspective on income distribution in China, from 1995 to 2014. This analysis of household-level data is complemented with analysis of regional inequality using the provincial level income and population data from the National Bureau of Statistics and Provincial Yearbooks. Full details of data sources and adjustments are provided in Kanbur et al. (2017).

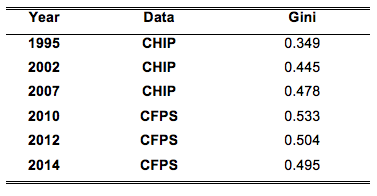

Table 1 presents the Gini coefficient for the six years covering 1995 to 2014. We see that the Gini coefficient has an inverted U-shaped pattern with the turning point at 0.533 in 2010. Similar trends are found for other inequality measures (Kanbur et al. 2017). Figure 1 shows that the income share of the top 10% reached its highest point in 2010, at around 0.4, and then declined.2 And the top-bottom decile income ratio went up from 1995 to 2012 and declined a little thereafter.

Table 1. Inequality measures from household survey data

Note: We adjusted CHIP income by excluding the components that are not in CFPS. CHIP 2007 uses the NBS survey data. Full details in Kanbur et al. (2017).

Figure 1. Decile income share (adjusted income)

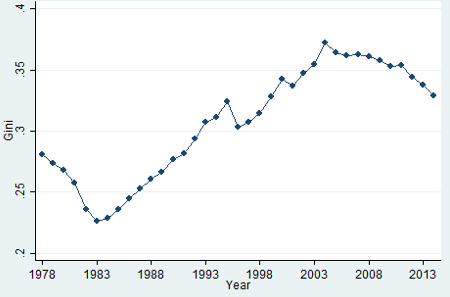

The combination of CHIP and CFPS data give us six observations spanning 1995 to 2014, all based on household surveys. An alternative methodological approach, useful for capturing long term annual trends, was introduced in Kanbur and Zhang (1999, 2005). This method uses NBS data on provincial consumption per capita broken down by rural and urban areas for each province. Combining this with rural-urban population data for each province, we can construct a synthetic national consumption distribution which assumes equality within rural areas and within urban areas of each province. Clearly, this will understate the level of inequality, but the trend over time may nonetheless convey useful information on how inequality has evolved.

Figure 2 presents the Gini coefficient over time for the synthetic distribution which focuses on regional inequality. Inequality went down a little after 1978 and started to climb after 1985. The Figure shows a peak in the mid-2000s, with a decline thereafter. Of course the values of the Gini coefficient in Figure 1 and Table 1 are not comparable since they come from different data sources and use different methods. However, the broad trends since the mid-1990s are similar for the two different time-perspectives – there appears to be an inequality turnaround sometime in the first decade of the 2000s.

Figure 2. Regional inequality in consumption per capita

What explains the turnaround? While a full explanation will require further detailed research, we can propose a number of hypotheses centred on the transformation of China from a rural/agrarian society towards an urban/industrial economy. In this framework, the national income distribution can be thought of as a weighted sum of the rural and the income distributions. The national inequality trend thus depends on three factors:

- The gap in average income between rural and urban sectors;

- Inequality within the rural and urban sectors; and

- The rate of urbanisation.

Zhang et al. (2011) have argued that China has now reached the ‘Lewis turning point’, where rural to urban migration begins to tighten rural labour markets and thereby mitigate the rural-urban wage differential. In addition, heavy government investment in infrastructure in the rural sector and lagging regions – a feature of Chinese policy since the 2000s (Fan et al. 2011) – would also raise economic activity and incomes in these areas.

A number of specific policy measures can be argued to have further mitigated inequality, by narrowing the spread within rural and urban areas. For example, in 2004 the Ministry of Labor and Social Security issued a ‘Minimum Wage Regulations’ law and the next decade saw rising minimum wages coupled with substantial improvements in compliance (Kanbur et al. 2016). Further, a number of social programs were introduced and strengthened from the 2000s onwards. Since 2004, China has introduced new rural cooperative medical insurance, currently covering more than 95% of the rural population. Rural social security has also been rolled out since 2009. Although the premiums of the rural medical insurance and social security are still much lower than for its urban counterparts, the programs have provided a cushion for rural residents against health risk and elderly care.

Concluding remarks

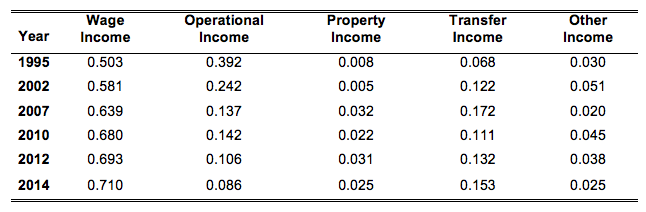

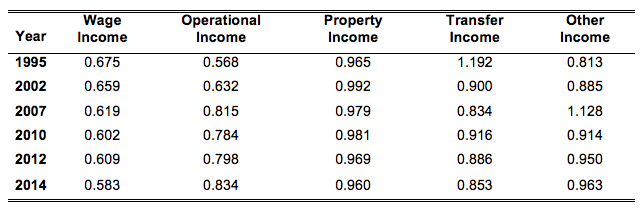

Thus, transfer and regulation regimes, combined with tightening labour markets in rural areas, have acted to mitigate inequality in China. Some evidence of this is found in Tables 2 and 3, which show the income share for each of a number of income sources and the Gini coefficients of income from each source. Inequality of wage income has fallen sharply, as has inequality of transfers. These are the dominant factors in total income, so their declining inequality is the dominant factor in the inequality turnaround. Further details of these calculations and interpretations are given in Kanbur et al. (2017).

Table 2. Share of income by source

Source: Kanbur et al (2017)

Table 3. Gini of income by source

Source: Kanbur et al (2017)

Finally, holding other factors constant, the rising share of urban population can, beyond a certain point, begin to contribute to inequality reduction. Kanbur and Zhuang (2013) have argued that while countries like India have yet to reach this turning point, China’s urbanisation rate has now taken it even further.

Our argument thus suggests that a number of forces have come together to mitigate the sharp rise in inequality seen in the first quarter century after the reform process. Chinese inequality is still high, with a Gini of around 0.5. But the rising trend has plateaued, and even begun to decline. There has been a great turnaround in Chinese inequality, and we now need to better understand the reasons for it, and the lessons that can be learnt from it.

References

Alvaredo, F, L Chancel, T Piketty, E Saez and G Zucman (2017) "Global inequality dynamics: New findings from WID.world',' NBER Working paper 23119.

Fan, S, R Kanbur and X Zhang (2011) “China’s regional disparities: Experience and policy”, Review of Development Finance, (1): 47–56.

Kanbur, R, Y Li and C Lin (2016) "Minimum wage competition between local governments in China", processed, Cornell University.

Kanbur, R, L Wang and X Zhang (2017) "The great Chinese inequality turnaround", CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11892.

Kanbur, R and X Zhang (1999) "Which regional inequality? The evolution of rural-urban and inland-coastal inequality in China, 1983-1995", Journal of Comparative Economics, 27: 686-701.

Kanbur, R and X Zhang (2005) “Fifty years of regional inequality in China: A journey through central planning, reform, and openness ", Review of Development Economics, 9(1): 87–106.

Kanbur, R and J Zhuang (2013) “Urbanization and inequality in Asia”, Asian Development Review, 30(1): 131–147.

Khan, A R and C Riskin (2005) “China’s household income and its distribution, 1995 and 2002”, The China Quarterly, 182: 356-384.

Zhang, X, J Yang and S Wang (2011) "China has reached the Lewis turning point", China Economic Review, 22(4): 542-554

Endnotes

[1] CHIP data was collected by China Academy of Social Sciences and Beijing Normal University, and CFPS data was collected by Peking University.

[2] Alvaredo et al. (2017) also show a recent decline in the share of the top of the distribution.