Providing firms with advertising and identity verification tools increases their hiring through a job portal, improving their ability to fill vacancies

Firms in lower-income countries often report difficulties finding skilled workers. At the same time, they rely heavily on their networks of family, friends, and co-workers to source new employees. This reliance on networks could limit the quantity or quality of hires (Chandrasekhar et al. 2020). Online job portals offer an opportunity to expand recruitment pools for firms but remain underutilized in urban India: only 2% of firms reported using the internet for recruitment in 2015-16 (National Sample Survey Office 2018). We partnered with an Indian job portal to better understand how firms use job portals and what recruitment services could assist them in expanding their hiring beyond their traditional networks (Fernando et al. 2023).

Recruitment challenges and the promise of online job portals

We surveyed small and midsized firms (employing fewer than 50 workers) in Bengaluru, India, that posted vacancies on QuikrJobs, an online job portal specializing in lower-wage occupations in the retail and services sectors. Though these firms were willing to search for workers online, two-thirds still reported recruitment-related constraints as a key barrier to their success. In fact, evidence from diverse settings suggests firms around the world often struggle to fill vacancies even when they search online (Fountain 2005, Hensel et al. 2021, Le Barbanchon et al. 2023). While firms in our setting listed their primary concern as locating applicants with suitable technical skills, more than half of firms also reported "trust-related” concerns about employee misbehaviour. These responses point to a dilemma facing firms: though job portals can expand applicant pools, concerns about screening workers are likely exacerbated when hiring online, which can limit the promise of job portals as a recruitment tool.

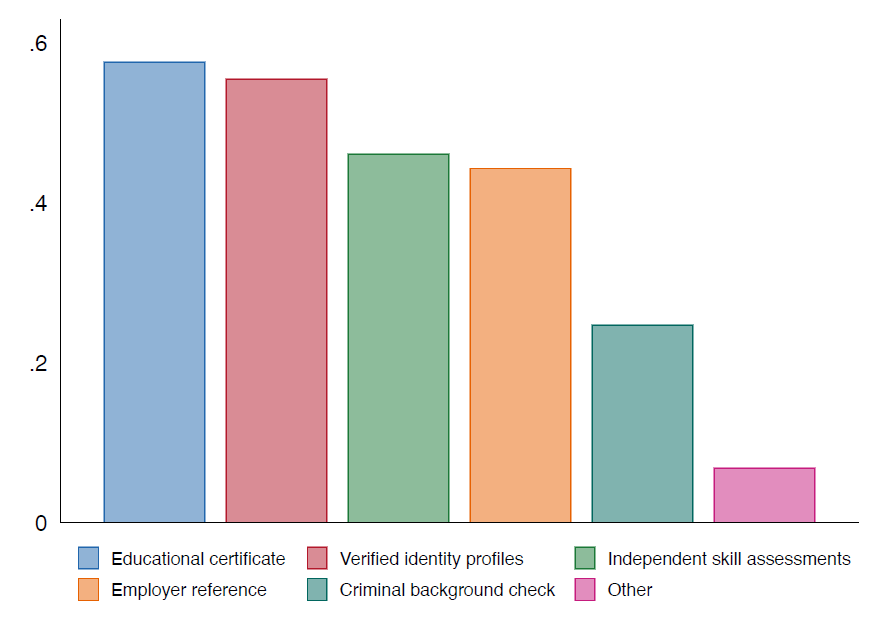

To understand how we could address employer concerns about portal-sourced applicants, we directly asked employers what information would help them hire from the portal. Notably, nearly all firms (98%) desire additional information on applicants. In Figure 1, we show that most employers requested identity-verified profiles and educational certificates, ahead of skill assessments and criminal background checks. When asked why they care about verifying identity, employers reported that it builds trust in applicants; it provided reassurance that applicants were honest, were less likely to steal or misbehave with customers, and were presenting truthful information on their profiles. Worries about employee trustworthiness and misbehaviour are also reported by firms in other lower-income countries (e.g. Bassi and Nansamba 2022, Caria and Falco 2022).

Figure 1: Applicant information desired by employers on the portal

Notes: This figure summarises additional applicant information desired by employers using the job portal, as reported in firm surveys collected by Fernando et al. (2023).

The study: Easing barriers to hiring

Motivated by the challenges mentioned by firms, we tested multiple interventions on the job portal that could improve hiring for firms. We randomly assigned 1,719 vacancies (1,576 firms) on the portal to one of the following groups:

- Premium advertising services (Scale): This treatment provided increased visibility to vacancies through time-limited, “top-of-page” placement and promotional emails and text messages to job seekers.

- Third-party identity verification of applicants (Verification): Employers in this treatment received identity verification results on their applicants via badges on applicants’ profiles. These badges captured whether an applicant had successfully verified their identity through voluntary submission of government ID documents.

- A combination of the two services (Joint): This intervention provided both advertising and identity verification services simultaneously.

- No additional services (Control): This group of vacancies experienced the portal as is.

We combined administrative data from the portal on vacancies and applications and original surveys with firms to understand how these interventions affected the recruitment process and hiring.

Key finding: Advertising and identity verification services jointly increased hiring from the portal, leading to greater overall hiring.

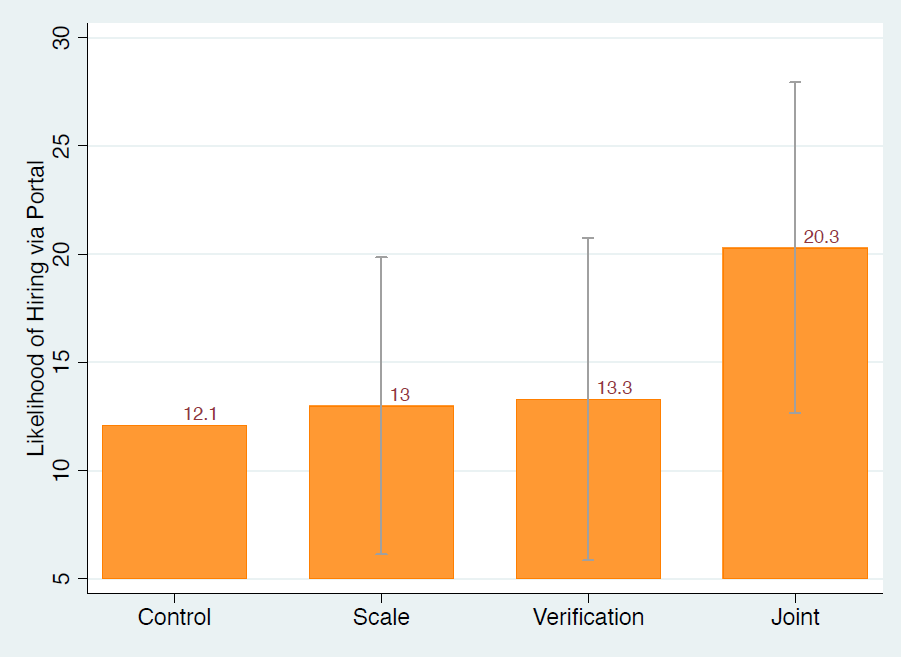

Firms in the Joint treatment were 68% or eight percentage points more likely to make a hire from the portal than Control firms (see Figure 2). To understand this impact, we mapped how the treatment affected the recruitment process. First, the treatment changed the applicant pools observed by employers. It doubled the number of applications. Strikingly, the average quality of applicants – measured by education, skills, and experience listed on applicant profiles – did not change, but the Joint treatment increased employers’ access to high skilled candidates. Second, combined with the verification information, these changes lead employers to increase their willingness to contact and interview applicants from the portal.

The increase in hiring from the portal for Joint firms did not come at the expense of hiring through networks. In fact, Joint firms reported an overall increase in the likelihood of hiring by 11%. Moreover, this hiring was not transient: six months after treatment, Joint firms were still more likely to report the presence of a portal-sourced hire.

In contrast to these large impacts for the Joint treatment, we recorded small and insignificant impacts on hiring for the individual treatments.

Figure 2: Portal hiring across treatments

Notes: This figure shows the likelihood of hiring from the QuikrJobs portal (for Control, Scale, Verification, and Joint). The orange bars represent the mean value of hiring in each group, and the vertical grey lines are 95% confidence intervals. Data is drawn from firm surveys.

When and why is identity verification valuable?

Understanding the lack of impacts on the individual treatments can shed light on what drives the large impacts in the Joint treatment. First, we note that employers in the Verification treatment received as many applications as those in the control group, but, due to the voluntary nature of verification information, only received additional information on five applicants. As most employers report simultaneously pursuing recruitment via networks, employers may simply have received too few verified applicants to consider hiring outside their networks. On the flip side, the Scale treatment had similar impacts on the quantity and quality of the applicant pools, but employers were less willing than in the Joint treatment to contact portal applicants. Thus, in the absence of screening tools, larger applicant pools may have left employers struggling to process the higher volume or still left employers unsure about whether applicants had desirable unobserved attributes such as trustworthiness.

The effectiveness of the combined treatment suggests that identity verification can be a valuable tool for employers, when the applicant pools are sufficiently thick. Employers may have perceived successful compliance of verification as a signal of applicant honesty, interest in the job, or ability. Armed with better information on applicants and access to more skilled applicants, employers in the Joint treatment were more willing to take a chance of applicants they would have otherwise not contacted. In fact, Joint employers spent greater overall recruitment effort and, perhaps as a consequence, filled more vacancies.

Implications

Difficulty locating suitable candidates is a commonplace concern for firms across the developing world and many are unable to hire outside their networks because of inadequate screening mechanisms (e.g. Abebe et al. 2021, Hardy and McCasland 2023). The proliferation of online job portals represents a technological advance that can greatly expand recruitment networks, but there remain challenges to encouraging firms to hire beyond traditional networks throughout the world: across a number of job portals, firms cite concerns about the quality and responsiveness of candidates (e.g. Cappelli 2001, Fountain 2005, CareerPlug 2020).

The results from this experiment show the promise of online job portals and the necessity of providing ancillary screening services in fulfilling that promise. Given the rapid proliferation of government-supported digital identity systems in lower-income countries (Gelb and Metz 2017), identity verification technologies could serve as a low-cost, scalable screening tool for improving labour market matching. Furthermore, future work could also consider embedding other forms of screening, such as skills certifications, on job portals.

Editor's note: This paper appeared as a STEG Working Paper.

References

Bassi, V and A Nansamba (2022), “Screening and signalling non-cognitive skills: experimental evidence from Uganda”, The Economic Journal 132(642): 471–511.

Cappelli, P (2001), “Making the most of on-line recruiting”, Harvard business review 79(3): 139–148.

CareerPlug (2020) “2020 Recruiting Trends: Benchmark Data by Industry”, Available at: https://www.careerplug.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Recruiting-Metrics-and-KPIs.pdf

Caria, S and P Falco (2022), “Skeptical Employers: Experimental Evidence on Biased Beliefs Constraining Firm Growth”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 1-45.

Chandrasekhar, A G, M Morten and A Peter (2020), “Network-Based Hiring: Local Benefits; Global Costs”, NBER Working Paper 26806.

Fernando, A N, N Singh and G Tourek (2023), “Hiring Frictions and the Promise of Online Job Portals”, Working Paper.

Fountain, C (2005), “Finding a job in the internet age”, Social Forces 83(3): 1235–1262.

Gelb, A and A D Metz (2017), “Identification Revolution: Can Digital ID Be Harnessed for Development?”, CGD Policy Brief

Hardy, M and J McCasland (2023), “Are Small Firms Labor Constrained? Experimental Evidence from Ghana”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 15(2): 253-284.

Hensel, L, T G Tekleselassie and M Witte (2021), “Formalized Employee Search and Labor Demand”, Institute of Labour Economics Discussion Paper, Available at: https://docs.iza.org/dp14839.pdf

Le Barbanchon, T, M Ronchi and J Sauvagnat (2023), “Hiring Frictions and Firms’ Growth”, SSRN Working Paper.

National Sample Survey Office (2018), “India - Unincorporated Non-Agricultural Enterprises (Excluding Construction) - July 2015 - June 2016, 73 round.”