The differential impact of parenthood on the employment of mothers relative to fathers – the child penalty – is a universal phenomenon, but with varying magnitudes. New evidence across 134 countries shows that typically, as countries grow wealthier, child penalties take over as the dominant driver of gender inequality.

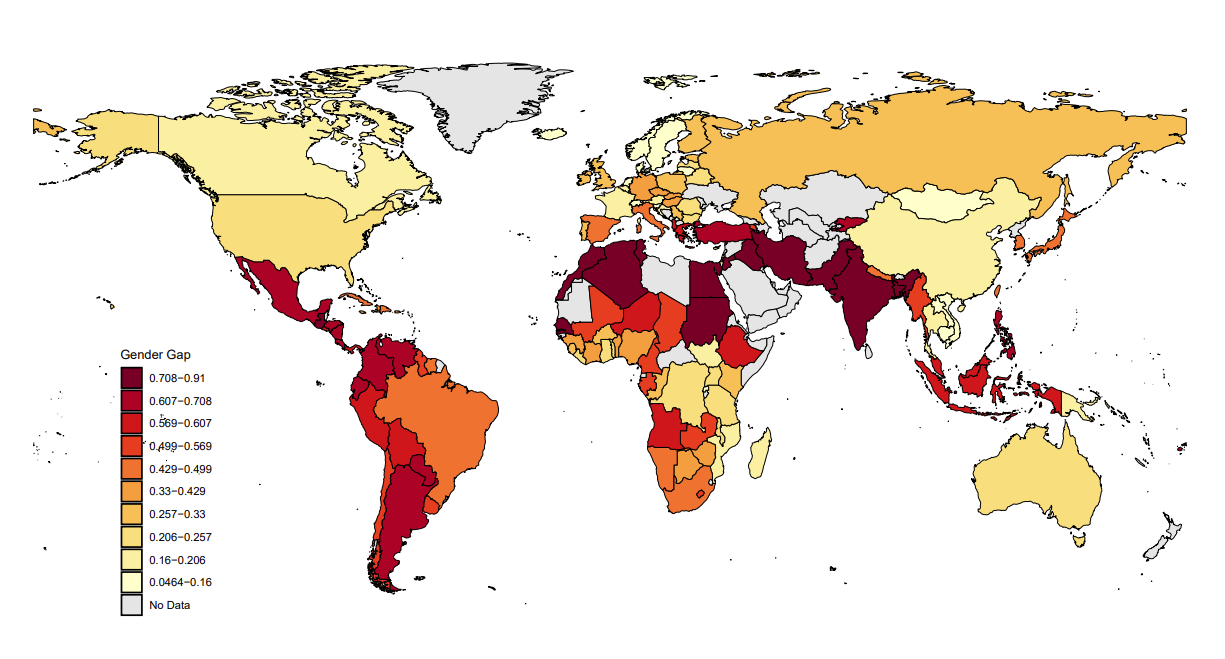

Despite significant progress in recent decades, the labour market gap between men and women remains substantial in almost all countries across different dimensions: employment, wages, promotions, and earnings (Olivetti and Petrongolo 2016, Costa Dias et al. 2021). Figure 1 illustrates the gender gap in paid employment around the world.

Figure 1: Map of gender gap

The differential impact of the arrival of a first child on the outcomes of men and women – the so-called child penalty – has been shown to account for a large share of gender gaps in the labour market. In Denmark, for example, the birth of a first child is associated with a long-term reduction of 20% in earnings and 13% in employment for mothers relative to fathers (Kleven et al. 2019) - the share of the gender gap in earnings that can be attributed to child penalties rose from about 40% in 1980 to more than 80% in 2013.

Using a new approach to measure child penalties in 134 countries

Until recently, evidence on child penalties using event studies has been limited to a small group of high-income countries due to strong data requirements (Kleven et al. 2019). This approach requires panel data on labour market outcomes over a long period of time, which is not available for most low and middle-income countries.

In The Child Penalty Atlas (Kleven et al. 2024), we overcome this limitation by employing the pseudo-event study approach developed by Kleven (2024). This approach allows the estimation of child penalties using widely available cross-sectional data. To conduct pseudo-event studies, we match recent parents with non-parents who are similar on several observable characteristics. The matched non-parents are then imputed with future children, creating a pseudo-panel that includes both true parents and synthetic future parents.

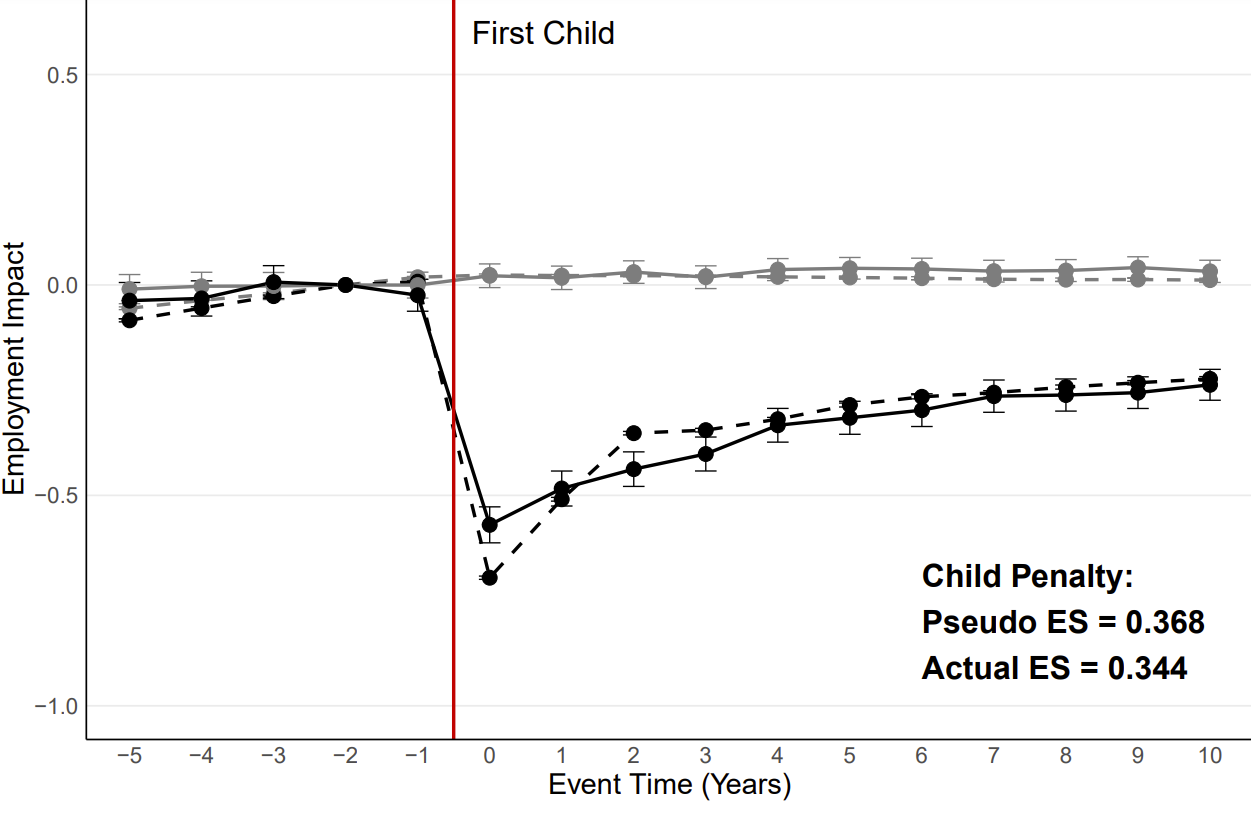

Using countries where we have access to panel data, we validate the methodology by comparing the actual event-study estimates with pseudo-event study estimates. The results are remarkably similar – Figure 2 illustrates the example of Austria.

Figure 2: Validation using data from Austria

Child penalties are a universal phenomenon with greatly varying magnitudes

Our method greatly expands the set of countries for which we can quantify child penalties. It allows us to estimate child penalties using a combination of household surveys and census data. Such data is widely available, even for low- and middle-income countries. We collect and harmonise nationally representative data for 134 countries around the world, representing more than 95% of the global population.

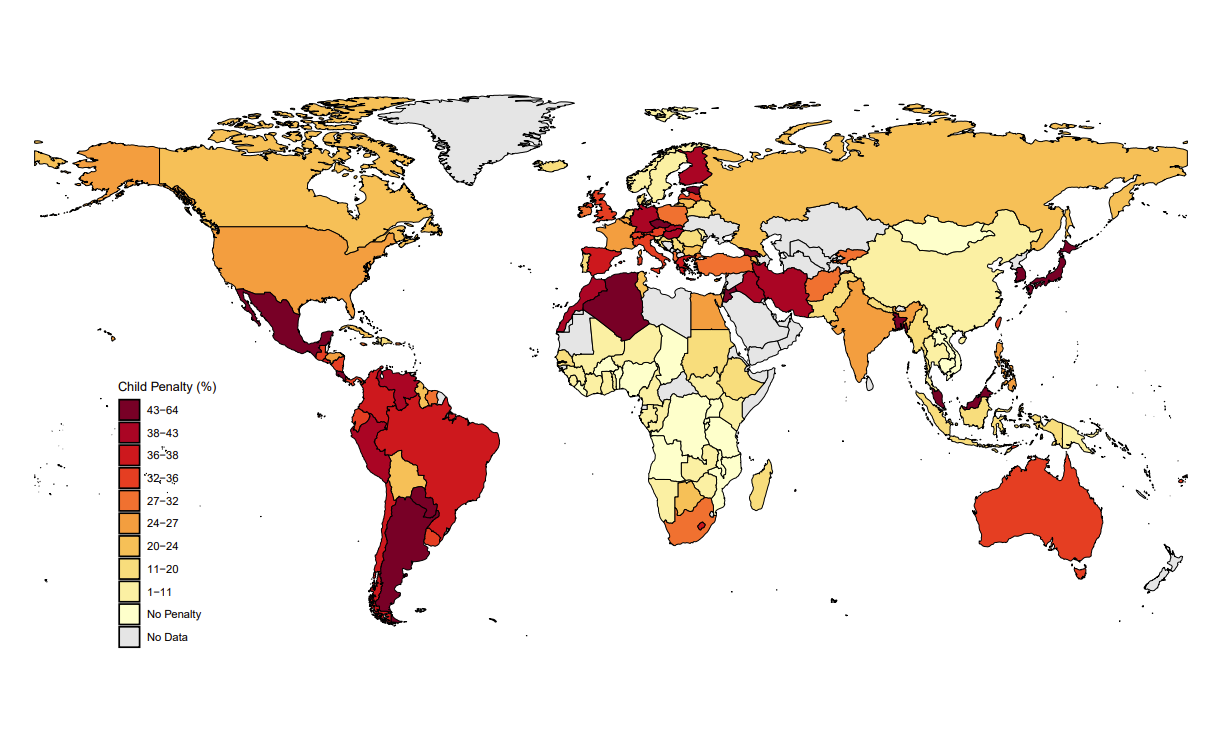

We calculate the child penalty in employment – i.e. how much the birth of a first child impacts the employment of mothers relative to fathers. Figure 3 presents a heatmap of child penalties around the world.

Figure 3: Map of child penalty across the world

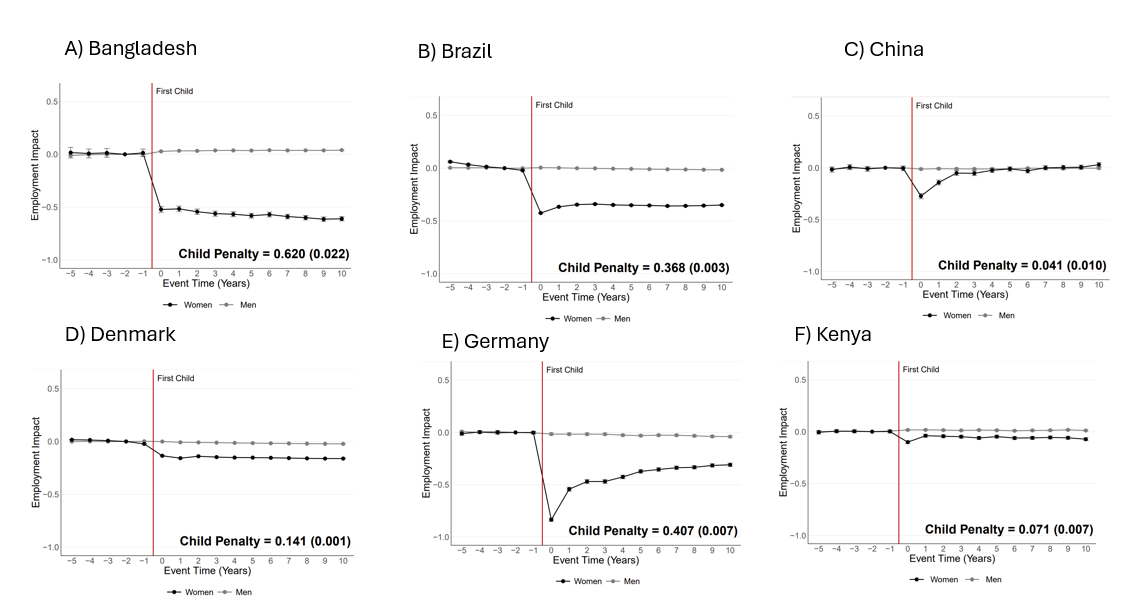

Our main finding is that, while child penalties are a near-universal phenomenon, their magnitudes vary tremendously across places. In almost every country, parenthood has a clear and persistent negative impact on women’s employment, while men’s employment is virtually unaffected. But the size of the penalty varies enormously. To see this better, Figure 4 presents event studies of the effect of first childbirth on employment for a selected set of countries.

Figure 4: Panel of different countries

In Denmark, the child penalty in employment is 14% - that means that women are, on average, 14% more affected than men in terms of the decrease in their probability of employment in the ten years after the birth of a first child. In the Germany, this figure is 41%. In Brazil, it’s 37%, in China it’s 4%, in Bangladesh it’s 62%, and in Kenya it’s 7%. On average, child penalties are the largest in Western Europe and Latin America, and the smallest in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia.

Why are child penalties so different across countries?

The large variation in child penalties raises important questions: what explains why child penalties are high or low? How much of gender inequality can be explained by child penalties in different types of societies? While we cannot establish causal relationships, we document a number of suggestive patterns.

Overall, the fraction of gender inequality explained by child penalties varies systematically with economic development and proxies for structural transformation. In low-income countries, child penalties tend to represent a small fraction of gender inequality. But as economies develop — incomes rise and the labour market transitions from subsistence agriculture to salaried work in industry and services — child penalties take over as the dominant driver of gender inequality.

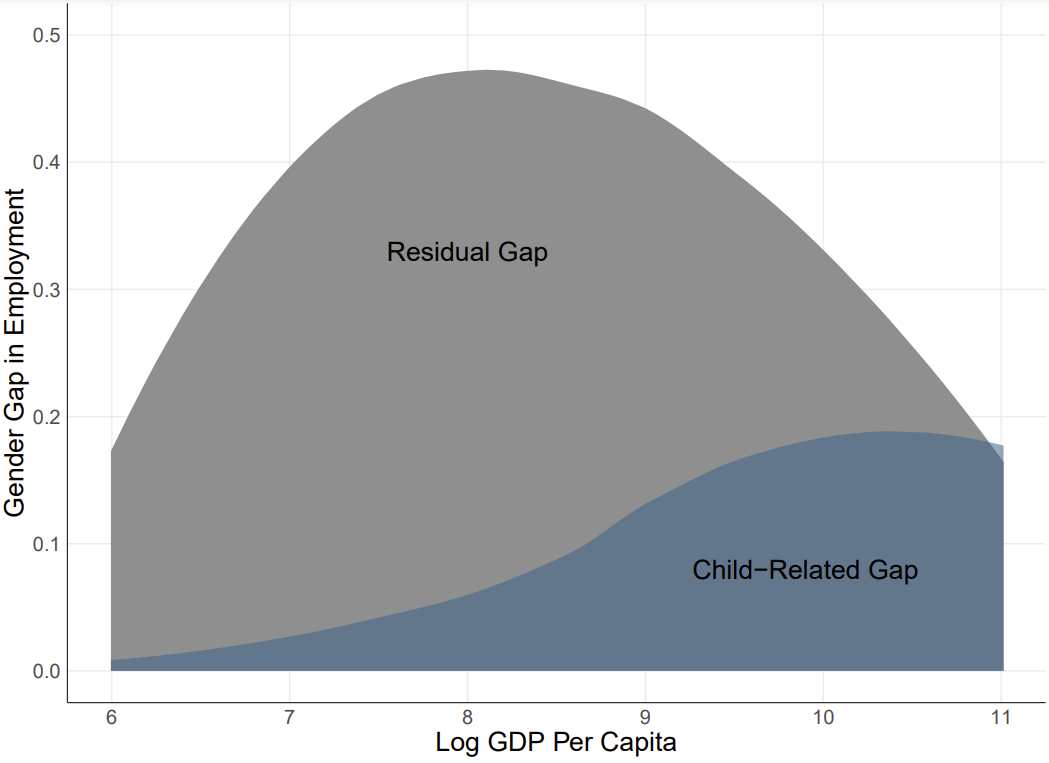

To illustrate this point, the figure below decomposes the total gender gap, by levels of GDP per capita, into a part explained by child penalties and a residual part capturing all other factors.

Figure 5: Decomposition of the gender gap between children and "unexplained"

In the lowest-income countries, there is a large gender gap, but almost no child-related gap. This means that the labour market inequality between men and women is driven by factors not directly linked to childbirth. As GDP per capita grows, child penalties increase. In middle-income countries, the child-related gap is significant, while the residual gap remains very high. As a result, the gender gaps in middle-income countries are the highest in the world. As countries achieve higher income levels, the overall gender gap starts to decrease, but the child-related gap is sticky. As a result, the child penalty takes over as the driver of gender inequality. In the highest-income countries, eliminating gender inequality is virtually synonymous with eliminating child penalties, consistent with the original findings by Kleven et al. (2019) for the specific case of Denmark.

A global map of child penalties in employment

Around the world, women’s labour market trajectories are much more affected by childbirth than men’s. In The Child Penalty Atlas, we build the first map of child penalties in employment with global coverage, documenting the magnitude of these penalties in 134 countries. We find that the existence of child penalties is almost universal, but their magnitudes vary dramatically. Child penalties are larger in high-income countries that have non-agricultural, urban, employee-based labour markets. While the preceding discussion documented this pattern in the cross-section of countries at different income levels, out Child Penalty Atlas validates these relationships using historical data from current high-income countries, going back to the 1700-1800s.

Our findings from the Child Penalty Atlas are publicly available and can be viewed at https://childpenaltyatlas.org/.

References

Andrew, A, et al. (2021), “Women and men at work,” The IFS. Available at: https://ifs.org.uk/publications/women-and-men-work (accessed: 10 December 2024).

Kleven, H, C Landais, and J E Søgaard (2019), “Children and gender inequality: Evidence from Denmark,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 11(4): 181–209.

Kleven, H (2024), “The geography of child penalties and gender norms: A pseudo-event study approach,” Working Paper No. 30176, National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w30176.

Kleven, H, C Landais, J Posch, A Steinhauer, and J Zweimüller (2019), “Child penalties across countries: Evidence and explanations,” AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109: 122–126.

Kleven, H, C Landais, and G Leite-Mariante (2024), “The Child Penalty Atlas,” Review of Economic Studies, rdae104.

Olivetti, C, and B Petrongolo (2016), “The evolution of gender gaps in industrialized countries,” Annual Review of Economics, 8(1): 405–434. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115329.