Could central banks co-investing in private companies hold a possible solution to many developing government budgetary issues?

Everyone these days seems focused on how central banks should spend their money: from formal models and assessments like Kang’s (2017) to the SRSrocco Report. Scholars like Dafe and Volz (2015) increasingly view central bank policy as a tool of international development, rather than something solely focused on banks and financial stability. In response to this view, a question is often raised: when interest rates fall to zero and growth stagnates, can central banks still affect economic growth outside of the usual fiscal and monetary policy models?

Central banks investing in private assets

In a recent article, my co-author and I show how central bank purchases of companies’ securities may hold the answer (Michael and Dalko 2017). The public knows of these purchases as ‘unconventional monetary policy’ when it works, and ‘helicopter money’ when it does not. Particularly in countries like Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, and even bigger economies such as India and Russia, central banks play a critical role in buying local stocks, bonds, asset backed securities and other ‘paper’ when domestic capital markets work badly. In some cases, like Bhutan and Thailand, central banks have enough resources to provide up to 50% of GDP to companies in need. Yet, as Japan shows, there is a catch. Since the end of 2010, the Bank of Japan has spent very large sums of money on private assets such as corporate bonds, with little effect on growth and/or inflation (Lam 2011). However, we believe this is not because the idea that central banks buying private assets is fundamentally flawed, but rather because Japan’s economy was not suited to such measures.

As we describe in our article, there is a set of criteria that countries should meet to be best able to take advantage of central bank investments as a funder of last resort:

- They should have tried the usual monetary tricks and failed (as shown by extremely low inflation and interest rates).

- They should have a long line of good ideas starved for money.

- Their central banks should work better, more independently, and more cleanly than their governments that spend during fiscal policy.

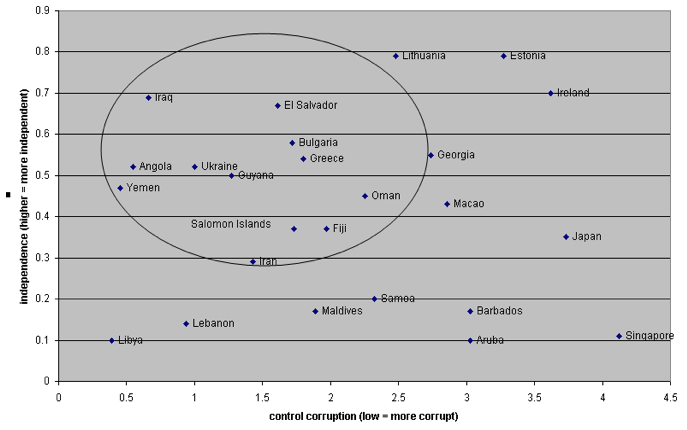

Figure 1 shows the countries we identified as preliminary candidates – before looking at whether central bank purchases actually encourage investment.

Figure 1 Candidates for growth through central bank private asset purchases

The need for central banks to have legislative authority

We further analyse the extent to which investment is linked with central bank private asset purchases – holding other variables constant. More specifically, the range of gross capital formation’s percent change relative to a 1% change in the central bank’s purchase of private sector assets. We find that real, tangible capital investment—in about half the countries we looked at—is associated with central bank investment in less tangible paper investments. The other half of these countries exhibit what we call a ‘sloth effect’. Firms in these countries invest less as their central bank buys more of their assets. Maybe firms increase spending rather than investing this cash.

The reasons? We find that most East Asian central banks do not have the clear and direct legislative authority to make such investments. In such cases, we argue that a statutory provision that requires central banks to target their country’s nominal GDP, is the easiest and most effective solution to this problem. Under such a scheme, a central bank becomes responsible for output as well as inflation. Giving central banks the responsibility to increase output and the authorisation to affect output (e.g., through investment as much as through other monetary channels) makes sense.

Ideas for central banks that do not have legislative authority

For countries unwilling or unable to change their laws, we offer other legal drafting ideas. Lawmakers can choose other avenues for allowing their central banks to purchase private sector securities – rather than imposing nominal GDP targeting requirements.

- For (mostly Latin American) countries, which give the government explicit power to make central bank rules, the president or prime minister can simply pass an executive decree. Such a decree would explicitly allow the central bank to buy private sector assets.

- For the much larger range of countries which already have provisions for dealing with stabilisation and the bank’s role as a lender of last resort, lawmakers could repurpose these provisions -- including the purchase of private sector securities as part of already defined stabilisation, macroprudential, and other policy. If the central bank act needs amending directly, lawmakers may also authorise these purchases from a special bank account to be used during crises and capped at a certain limit.

- Finally, particularly in the context of a monetary union, lawmakers can introduce the authority to buy these assets as part of the international treaty or agreement governing the monetary union’s central bank (in places like Europe, West Africa and the Caribbean).

Most of East Asia’s recent history features thrifty central banks. We do not want to return to that time. Yet, new data show that targeted central bank investments may help promote growth in places like Laos, Myanmar, or even China and India – as long as they have their own monetary policy, which has not worked in the past.

Your central bank as a co-investor in your company may not be too far away. Who would have thought that East Asia’s central banks can rescue, rather than be rescued?

References

Dafe, F and U Volz (2015), "Financing global development: The role of central banks", German Development Institute Briefing Paper 8/2015.

Lam, W R (2011), "Bank of Japan’s Monetary Easing Measures: Are They Powerful and Comprehensive?", IMF Working Paper No. 11/264.

Michael, B and V Dalko (2017), “Funders-of-last-resort: Legal issues involved in using central bank balance sheets to bolster economic growth”, working paper.

Kang, K Y (2017), “Central Bank Purchases of Private Assets: An Evaluation”.