When extreme natural events strike, investors move money away from emerging economies at higher climate risk in search of climatic safety

Editor's note: This column originally appeared on VoxEU.

Weather-related natural disasters are increasing in frequency and intensity worldwide because of climate change. Their economic consequences are highly heterogeneous across countries, as some countries are more exposed or more vulnerable than others (Rossi-Hansberg and Cruz 2021, Blanchard and Tirole 2022). This heterogeneity may have profound financial implications at the global scale. However, while the economic analysis of climate change and natural disasters has often adopted a multi-country perspective (Dell et al. 2014, Botzen et al. 2019), evidence of the effects of local climate events beyond country borders is rare at best. Notable exceptions are Gu and Hale (2023) and Hale (2023), who study the implication of natural disasters for foreign direct investment and exchange rates, respectively. We take up this issue by investigating whether these events can shape international investors' portfolio flows. We construct a multi-country weekly dataset tracking the occurrence of large natural disasters and net inflows to equity mutual funds by destination country.1 We employ the dataset that spans 2009-2019 to study the effect of extreme natural events on global financial flows.2

The Typhoon Haiyan case study

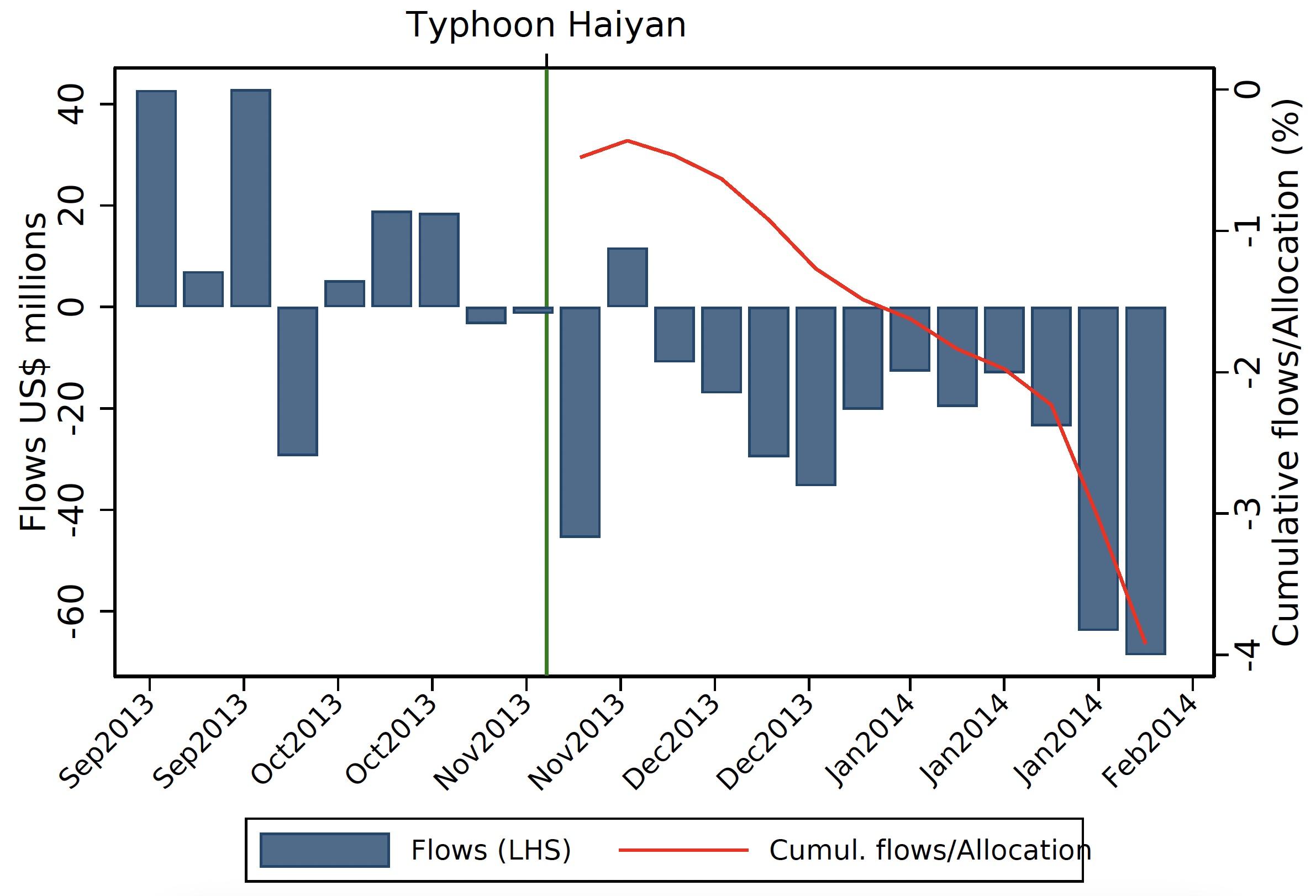

A neat illustration of the mechanism we uncover is exemplified by the dynamics of net inflows to mutual funds investing in the Philippines before and after Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 (Figure 1). Whereas, before the disaster, equity flows to the country were fluctuating, after the typhoon a clear and persistent pattern of capital outflows emerged. We generalise this narrative and investigate the drivers underlying this phenomenon through rigorous econometric analysis.

Figure 1: Case study: Impact of Haiyan Typhoon on equity portfolio flows to the Philippines

The impact of natural disasters on portfolio flows

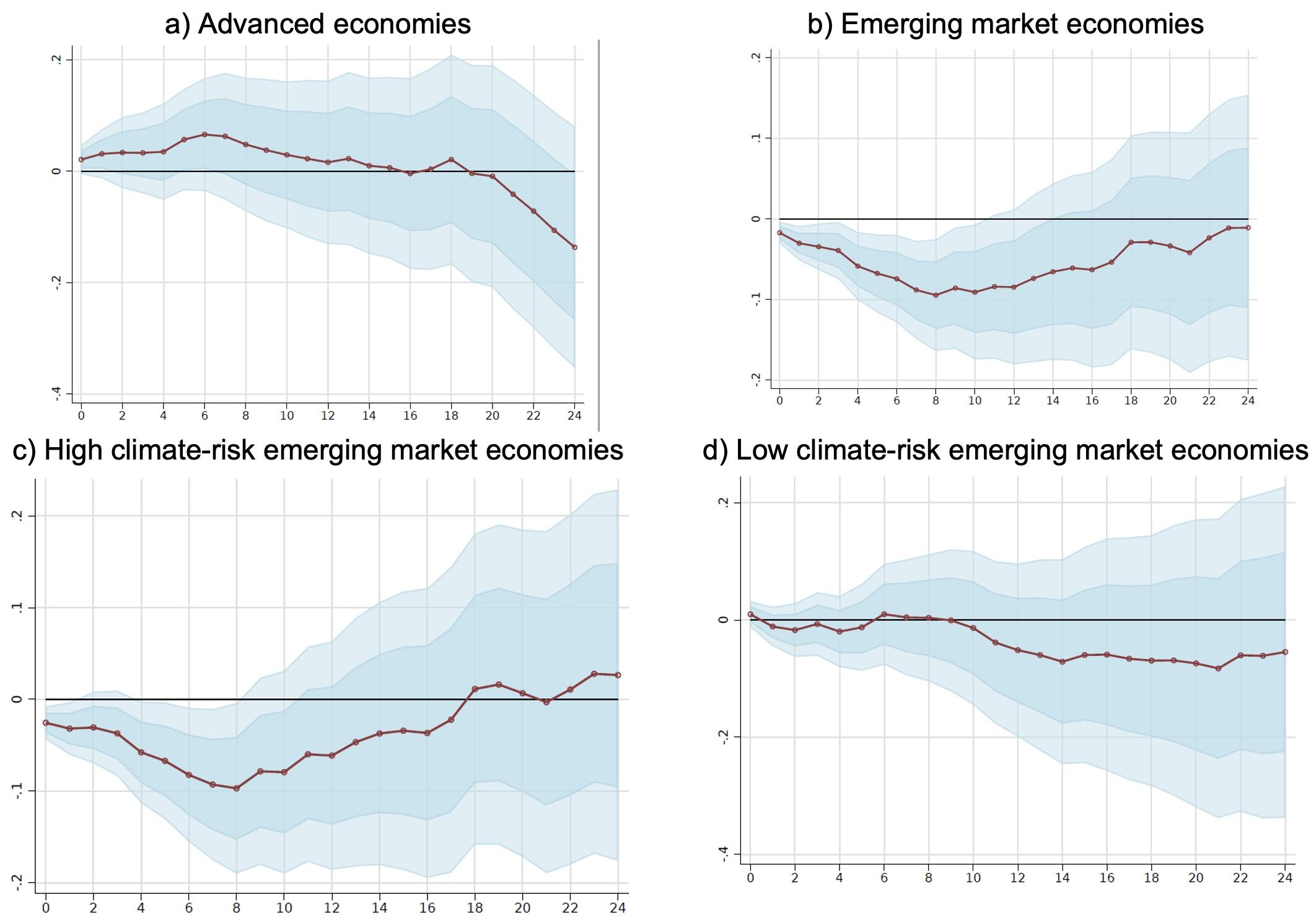

In our recent paper (Ferriani et al. 2023), we use several panel regression models to estimate the effect that natural disasters exert over time on portfolio equity flows.3 Our estimates point to a significant response of international investors exclusively when disasters hit emerging economies (EMEs), in particular those classified as the most vulnerable to climate change, see Figure 2.4 Inflows to these countries drop gradually after the disasters unfold, with inflows remaining persistently subdued for about three months. The cumulated impact of each event at its maximum is, on average, associated with a 0.1 percentage point decrease in net portfolio flows (scaled by asset under management), a sizable effect if compared with average weekly net flows that are equal, in our sample, to 0.16%.5 Conversely, advanced economies and less climate-vulnerable EMEs do not see a reduction in capital inflows.

Figure 2: Impact of natural disasters on equity portfolio flows

Note: Impact of natural disasters on equity portfolio flows, the horizon is weekly; coefficients represent percentage points, with 68% and 90% confidence bands.

Search for climatic safety

What drives the response of investors? Disasters can physically disrupt the productive structure of the economy and investors may pull out of the country due to the fall in expected cash flow. Our analysis suggests, however, that the investors’ behaviour is primarily driven by an update of beliefs on the global climatic threat. This conclusion builds on two additional results. First, we show that investors pull out even from neighbouring countries that have not been directly hit by a disaster but that are arguably subject to the same climatic risks. This result holds even controlling for trade linkages between neighbouring countries, i.e. net of any spillover effect coming from the disaster.

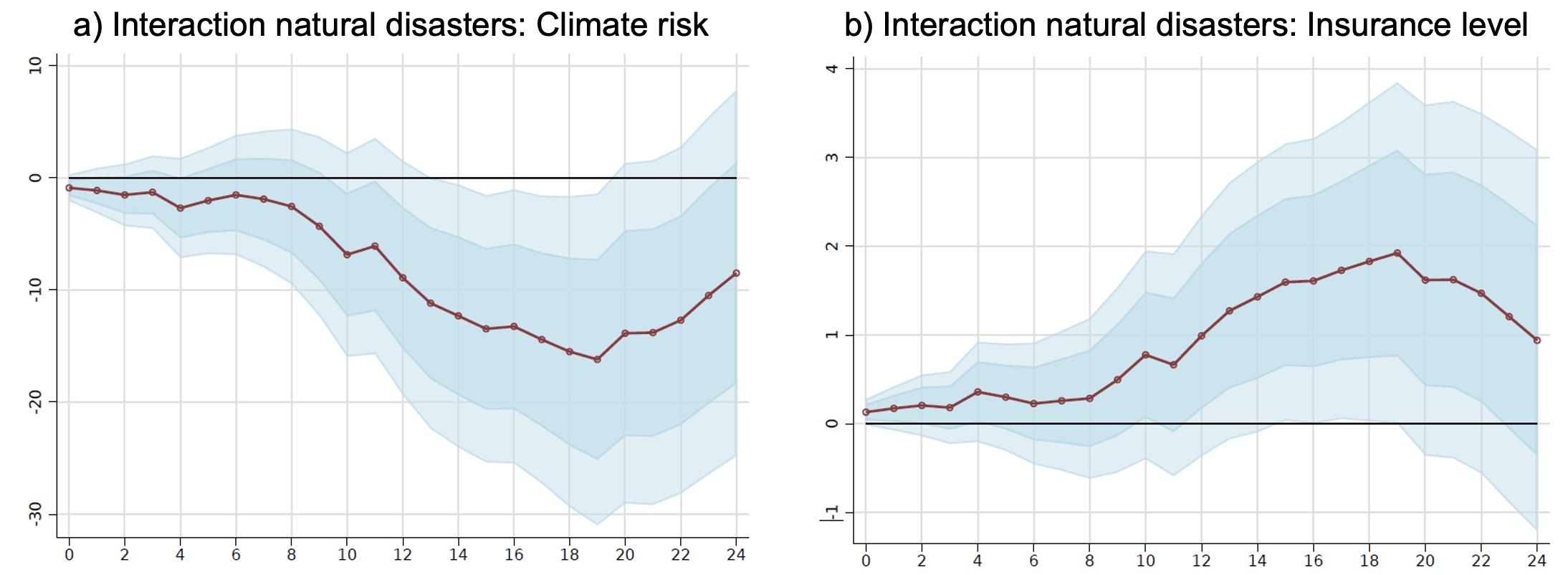

Second, after a disaster occurs in climatic-vulnerable EMEs, advanced economies benefit from increased inflows proportionally to both their exposure to climatic risk and their level of insurance to climatic events (Figure 3).6 Among advanced economies, traditional safe haven countries such as Japan, Germany, and Switzerland, which are typically beneficiaries of standard flight-to-safety episodes, do not receive heightened flows in response to natural disasters occurring in high climate-risk EMEs. Taken together, these results suggest that international investors flee countries that are risky from a climatic standpoint and recompose their portfolios towards safer economies that are also more resilient to future natural disasters. The occurrence of such events appears to raise investors’ attention towards the global climatic threat, shaping their beliefs about the portfolio risks attached to the invested countries. According to this interpretation, disasters can shape mutual funds inflows and outflows by triggering a specific flight-to-safety motive for trading, based on the perceived climate risk of the invested assets – a flight to climatic safety. Importantly, all these results hold after multiple robustness tests where we use alternative measures of portfolio flows, climatic riskiness, insurance level, definitions of climate events, and controls for each countries’ fiscal capacity.

Figure 3 Spillovers to advanced economies

Note: Spillover from high-risk EMEs to AEs. The left plot displays the IRFs of the interaction term between ND-GAIN vulnerability index and the dummy for natural events occurrence in HCR EMEs; the right plot displays the IRF of the interaction term between non-life insurance coverage and the dummy for natural events occurrence in HCR EMEs. The horizon is weekly; coefficients represent p.p., with 68% and 90% confidence bands

Conclusions and policy implications

We uncover a novel and relevant dimension through which climate change affects the global economy that was previously disregarded in the international finance literature. Going ahead, these portfolio movements are likely to become more sizable and volatile as climatic disasters increase in frequency and intensity over time due to climate change, raising uncertainty about financial capital availability at the country level. These findings are relevant for the policy debate on the design of effective mitigation and adaptation policies at a regional scale.

References

Blanchard O and J Tirole (2022), “Major future economic challenges”, VoxEU.org, 21 March.

Botzen, W J W, O Deschenes, and M Sanders (2019), “The Economic Impacts of Natural Disasters: A Review of Models and Empirical Studies”, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 13: 167–188.

Ciminelli, G, J Rogers, and W Wu (2022), “The effects of U.S. monetary policy on international mutual fund investment”, Journal of International Money and Finance 127, 102676.

Dell, M, B Jones, and B Olken (2014), “What Do We Learn from the Weather? The New Climate-Economy Literature,” Journal of Economic Literature.

Ferriani, F, A Gazzani and F Natoli (2023), “Flight to climatic safety: local natural disasters and global portfolio flows”, available at SSRN.

Gu, G W and G Hale (2023), “Climate risks and FDI,” Journal of International Economics, 103731.

Hale, G (2023), “Climate Risks and Exchange Rates,” mimeo.

Jordà, Ò (2005), “Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections,” American Economic Review 95: 161–182.

Rossi-Hansberg, E and J L Cruz (2021), “Unequal gains: Assessing the aggregate and spatial economic impact of global warming”, VoxEU.org, 2 March.

Footnotes

- The data on natural disasters comes from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) of the University of Louvain. Data on portfolio equity is provided by the Emerging Portfolio Fund Research (EPFR) dataset.

- For ease of exposition, we consider natural disasters and extreme weather events as interchangeable.

- We estimate the dynamic causal effect using local projections (Jorda 2005).

- According to the vulnerability component of the University of Notre Dame-Global Adaptation Index (ND-GAIN). We define vulnerable EMEs as those countries above the median.

- The obtained effect on net flows is roughly equivalent to a 5 basis point US monetary shock, based on the study of the impact of US monetary policy shocks on EME mutual funds provided in Ciminelli et al. (2022).

- Insurance is measured as the amount of non-life insurance premium to GDP (as %) obtained from the World Bank.