For decades, unexploded ordnances from the "Secret War" in Laos have hindered the structural transformation and economic growth of the country. Laotians' health, education, and migration decisions remain affected by this war even though the conflict officially ended in 1975.

The destructive nature of conflict is hard to overemphasise. Armed confrontations bring havoc not only to combatants but also to local businesses and innocent bystanders. The World Bank estimates that immediately after a typical civil war, a country’s GDP is 15% lower, and its citizens face increased poverty rates of up to 30% (Collier et al. 2003, Collier 2007, Federle et al. 2024).

While the short-term effects of war have been extensively documented in previous research (Blattman and Miguel 2010, Bauer et al. 2016), its ultimate long-term consequences have been harder to estimate. Several studies have found no long-lasting impacts after bombings in Japan, Germany, and Vietnam (Davis and Weinstein 2002, Brakman et al. 2004, Miguel and Roland 2011). Others, echoing the quip by Charles Tilly that “War made the state, and the state made war”, have even argued for the potential state- and fiscal-capacity gains emerging from war (Dincecco and Onorato 2018, Voigtländer and Voth 2012).

This emphasis on postwar recovery appears at odds with the “Conflict Trap” hypothesis (Collier 1999), according to which countries remain poor partly due to conflict. In our research (Riaño and Valencia 2024), we challenge this emphasis on long-term recovery by testing whether a conflict trap hypothesis fits the current status in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. From 1964 to 1975, this country suffered one of the most intensive bombing campaigns in human history, and today, it remains one of the poorest countries in the world. Are these two sides of the same coin?

The “Secret War” in Laos and the remnants of conflict

The Laotian Civil War (1953-1975) can be understood as a classic Cold War conflict. It pitted the Communist Pathet Lao against the Royal Lao Government. As part of its Cold War counterinsurgency operations in Southeast Asia, the US government conducted a series of military campaigns in Laos from 1964-1975. Given the neighbouring conflict in Cambodia and Vietnam, the country was of fundamental geostrategic interest. Though the US intervened in Laos all those years, the conflict remained secret at the time, as it was only internationally acknowledged in 2016 by Barack Obama. In total, during this “Secret War,” over 270 million cluster bombs were dropped in the country, a third of which did not explode, comprising a significant hazard for the Laotian population today.

Could this historical conflict be one of the fundamental drivers of Lao’s underdevelopment?

To address this question, we combine highly disaggregated data on the incidence of conflict from 1964 to 1973 with multiple economic indicators in recent years. We employ information on more than 1.6 million bombing missions, that have recently been declassified by the US Department of Defense, with nighttime light data from the US Air Force Defense Meteorological Satellite Program. We complement this income proxy using actual development outcomes from the Laotian population and agricultural censuses, allowing us to explore the effects of conflict across time and space. Our empirical strategies allow us to 1) address the potential endogeneity of conflict to estimate causal effects and 2) take into account the timing of the bombings and the differential exposure of cohorts to the aerial campaigns and their byproducts. We also make use of administrative data on geo-located UXO accidents from the National Regulatory Authority for Mine Action in Laos, covering daily incidents from 1950 to 2011, which we use to test this primary mechanism of transmission.

Based on this data and our complementary methodological approaches, we derive four key lessons.

Lesson 1: Yes, conflict could result in harmful and long-lasting effects on economic development

Post-conflict recovery should not be taken for granted. We find that regions that endured more intense bombings during the “Secret War’’ exhibit significantly lower levels of economic development even 50 years after the war officially ended. Despite years of economic policy, these areas are not only less economically active, as measured by their lower levels of luminosity, but exhibit higher poverty rates and lower levels of per capita consumption than less bombed regions. Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that a one standard deviation increase in bombing intensity is associated with a persistent 7% decrease in GDP per capita for the whole country.

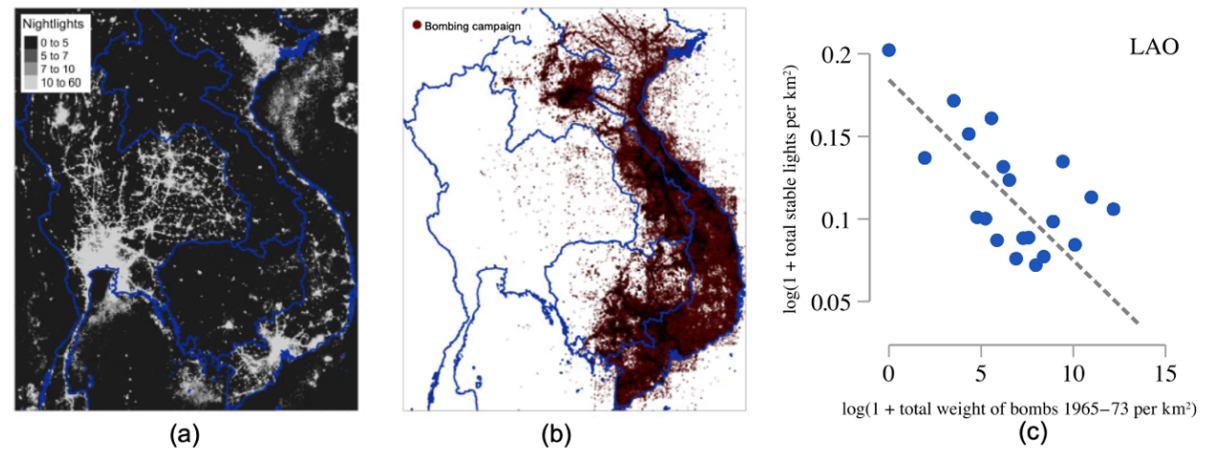

Figure 1: Indochina: Stable Lights and US Bombing Events from 1965 and 1973

Notes: Panel (a) displays the Indochina peninsula and the 2013 stable nightlights in grayscale. Country borders are displayed using a continuous line. Panel (b) displays the Indochina peninsula and the US Bombing Campaigns in the region from 1965 to 1973 in a dot distribution map. Each dot represents a single campaign. Country borders are displayed using a continuous line. Panel (c) presents a bin-scatter for Laos between Luminosity and Bombing intensity, controlling for province-fixed effects, year-fixed effects, and geographical and location covariates.

Lesson 2: The impact of conflict on human capital accumulation and structural transformation might explain the persistence of these adverse economic effects

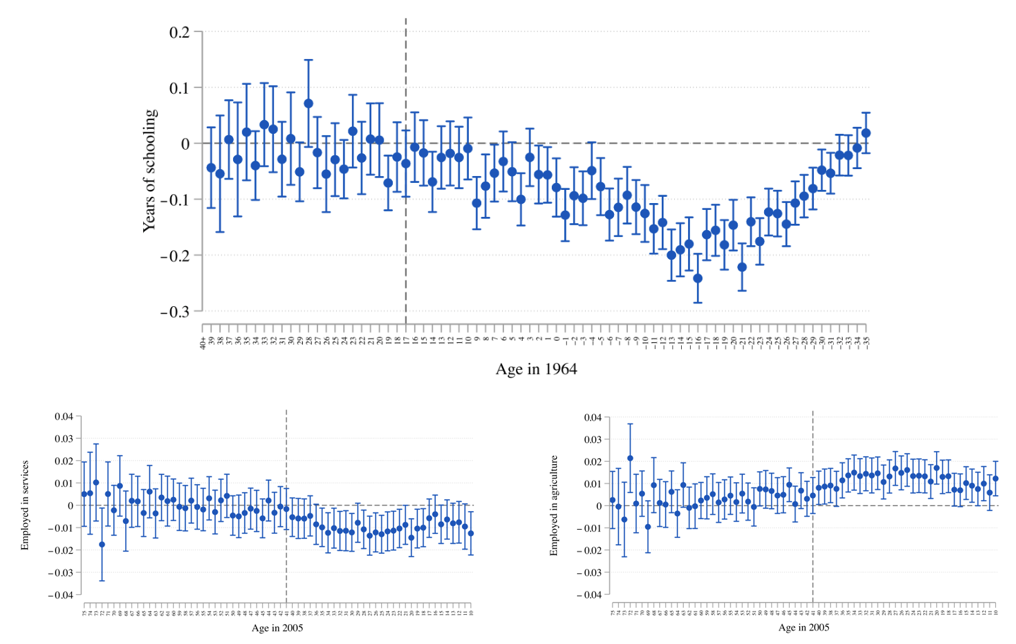

War can have long-lasting effects on countries’ incentives to invest in education and promote careers that require high levels of human capital. In Laos, regions that were heavily bombed during the war show persistently lower levels of human capital accumulation. This is evident in the reduced years of schooling and literacy rates in these areas, which have also disrupted the country's structural transformation. As a result, people from these impacted regions, when they reach their productive years, are more likely to work in sectors requiring less human capital, such as agriculture, rather than service-oriented sectors. These effects are particularly pronounced among those individuals born during the conflict and even more so among those born shortly after the conflict ended.

Figure 2: Impact of conflict on years of schooling and sector of employment

Notes: Top panel: The estimation sample includes individuals from 10–98 years old in 2005. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals are plotted for the difference between heavily affected regions vs. less affected regions. The outcome variable is years of schooling. The excluded cohort is composed of individuals who were forty or more years old in 1964. The seventeen-year-old cohort is marked with a vertical dashed line as a reference point. It corresponds to the age at which Laotians should have finished high school. The bottom left and right panels show the same differences when the outcomes are dummies of being employed in the agricultural sector (right) or in the service sector (left).

Lesson 3: Conflict could also lead to permanent losses in concentration of economic activity, making the country’s recovery harder to achieve

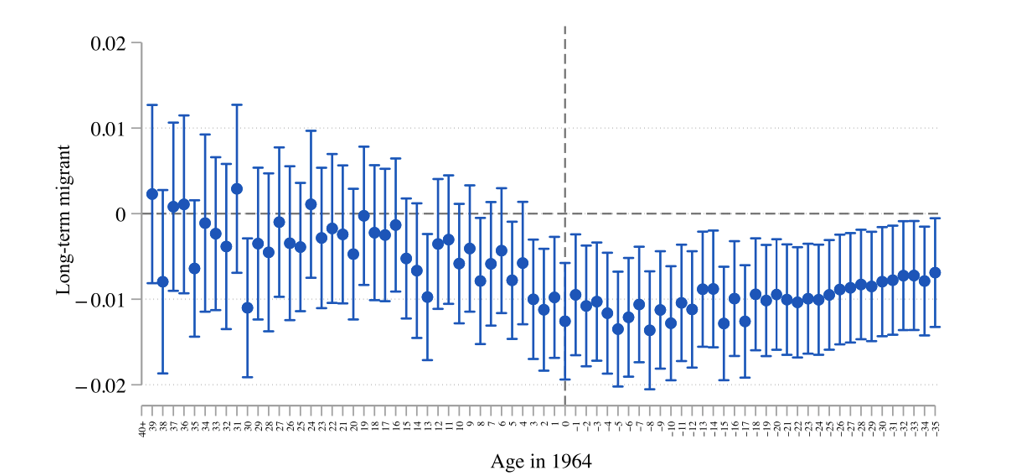

Conflict can have long-lasting effects on the benefits derived from agglomeration. In Laos, regions that experienced heavier bombing during conflict show a significant and enduring reduction in internal migration rates. These areas also exhibit lower population densities today, indicating that the disruptive impact of conflict has a sustained adverse effect on the concentration of economic activity and population centers. Reduced internal migration means fewer opportunities for labour market complementarities, lower urbanisation rates and less innovation and knowledge spillovers, all crucial for economic growth.

Figure 3: Impact of bombing on the probability of migration

Notes: Using Micro-Level Data from the Population Census of 2005 (Yearly): Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals are plotted for the difference between heavily and not-so-heavily bombed regions by cohort when the outcome variable is an indicator of being a long-term internal migrant. We define long-term migration as living in a province different from that at birth. The excluded cohort is composed of individuals who were forty years old or older in 1964. The zero-year-old cohort is marked with a vertical dashed line as a reference point.

Lesson 4: A significant fraction of the long-lasting effects of conflict could be attributed to the remnants of war, an aspect often forgotten by policymakers

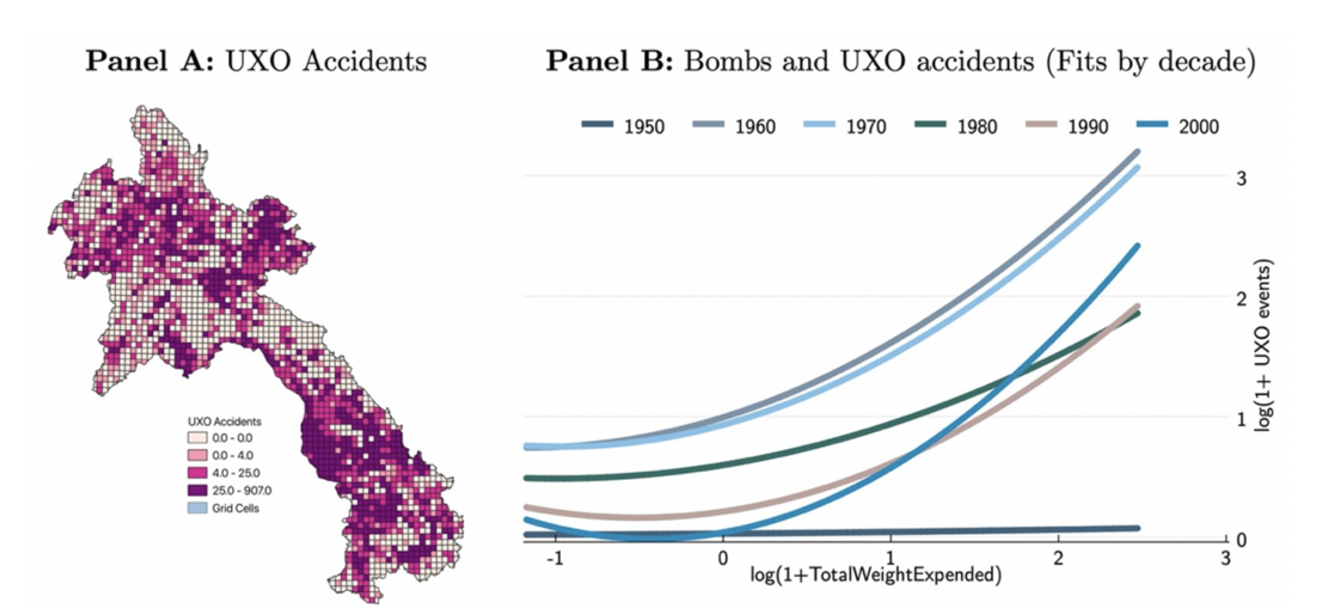

Migration, education, and labour market distortions caused by conflict can partially explain long-term impacts on economic development. However, why do these persist for so many years? Our research argues that these effects become long-lasting due to the compounding effects generated by the remnants of war, particularly unexploded ordnance (UXO). Using a simple structural model, we estimate that approximately 1/3 of the total reduction in economic activity in Laos can be attributed solely to UXO and its broader impacts on individual decisions. It is estimated that around 50,000 Laotians, most of them civilians, including children, have been killed or injured by American bombs. However, less than 1% of these latent munitions have been cleared. At the current pace, it could take more than 100 years to clear the country, making it the number one development issue in Laos (Boddington and Chanthavongsa 2008).

Figure 4: UXO contamination in Laos

Notes: Panel A of this figure depicts the spatial distribution of UXO accidents (events involving death, disability, or major injury) at the grid cell level in Laos. Panel B presents the relationship between intensity of the bombing campaigns in the country and the number of UXO accidents by decade.

Further policy implications for post-conflict reconstruction

Our results highlight the critical need for sustained investment in demining and public infrastructure to mitigate the long-term impacts of conflict. Clearing UXO might improve safety and enhance agricultural productivity and broader economic development (Lin 2020, 2024). Our findings advocate for comprehensive post-conflict reconstruction policies that address both immediate and lingering consequences of war, ensuring regions receive the necessary support for long-term growth, as proposed for Ukraine (Munroe et al. 2023). This includes policies promoting human capital investments, re-densification of previously affected areas, and investments in sectors requiring high levels of human capital.

These insights can also better inform policies for affected and attacking countries. For instance, recent works highlight how the demining agenda might be prioritised in conflict-stricken areas where the benefits of market access post-demining might be the largest (Chiovelli et al. 2018) and where the complex interactions of the different forms of demining are key (Prem et al. 2023). Local leaders can use these results to refine existing policies or implement new programmes targeting the enduring effects of UXOs. Policymakers in attacking countries should also consider the long-term socioeconomic impact of their military strategies, balancing immediate political and strategic goals against the significant and enduring economic costs of war.

References

Bauer, M, C Blattman, J Chytilová, J Henrich, E Miguel, and T Mitts (2016), "Can War Foster Cooperation?" Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3): 249-74.

Blattman, C, and E Miguel (2010), "Civil War," Journal of Economic Literature, 48(1): 3-57.

Boddington, M, and B Chanthavongsa (2008), National Survey of UXO Victims and Accidents. Report National Regulatory Authority for UXO/Mine Action Sector in Lao PDR (NRA).

Brakman, S, H Garretsen, and M Schramm (2004), "The strategic bombing of German cities during World War II and its impact on city growth," Journal of Economic Geography, 4(2): 201-218.

Davis, D, and D Weinstein (2002), "Bones, Bombs, and Break Points: The Geography of Economic Activity," American Economic Review, 92(5): 1269–1289.

Chiovelli, G, S Michalopoulos, and E Papaioannou (2018), "Landmines and Spatial Development," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. 24758.

Collier, P (1999), "On the economic consequences of civil war," Oxford Economic Papers, 51(1): 168–183.

Collier, P, V L Elliott, H Hegre, A Hoeffler, M Reynal-Querol, and N Sambanis (2003), Breaking the Conflict Trap: Civil War and Development Policy. World Bank policy research report. World Bank and Oxford University Press.

Collier, P (2007), The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It. Oxford University Press.

Dincecco, M, and M Onorato (2018), From Warfare to Wealth: The Military Origins of Urban Prosperity in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Federle, J, A Meier, G Müller, W Mutschler, and M Schularick (2024), "The Price of War," CEPR Discussion Paper No. 18834. CEPR Press, Paris & London.

Fergusson, L, A Ibáñez, and J Riaño (2020), "Conflict, Educational Attainment, and Structural Transformation: La Violencia in Colombia," Economic Development and Cultural Change, 69(1): 335–371.

Lin, E (2020), "How war changes land: Soil fertility, unexploded bombs, and the underdevelopment of Cambodia," American Journal of Political Science, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12577.

Lin, E (2024), When the Bombs Stopped: The Legacy of War in Rural Cambodia. Princeton University Press.

Miguel, E, and G Roland (2011), "The long-run impact of bombing Vietnam," Journal of Development Economics, 96(1): 1–15.

Munroe, E, A Nosach, M Pedrozo, E Guarnieri, J F Riaño, A Tur-Prats, and F Valencia Caicedo (2023), "The legacies of war for Ukraine," Economic Policy, 38(114): 201-241. https://doi.org/10.1093/epolic/eiad001.

Prem, M, M E Purroy, and J F Vargas (2023), "Landmines: The local effects of demining," Working paper, Available at SSRN.

Riaño, J F, and F Valencia Caicedo (2024), "Collateral Damage: The Legacy of the Secret War in Laos," The Economic Journal, 134(661): 2101-2140. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueae004.

Voigtländer, N, and H Voth (2013), "The Three Horsemen of Riches: Plague, War, and Urbanization in Early Modern Europe," The Review of Economic Studies, 80(2): 774–811.